-

Books

-

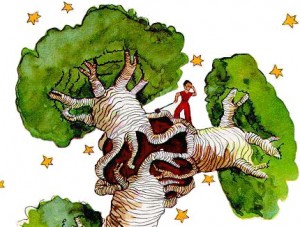

Notes on Death and the Resurrection of Children’s Fiction

by Audrey Schomer February 29, 2012

The first time I’d read it, at 11, it was about a boy, because I was young. The second, at 19, it was about love, because I was in love. This time around, it was about death. And because it was about death, it was about everything else, too, juxtaposed with death.

-

John Jeremiah Sullivan’s Pulphead

by Robert Carver February 21, 2012

Creative non-fiction: regardless of where one stands on the debate of which of those two modifiers rules the other — and to what degree — for everyone, there is a line.

-

Self-made Enigma: Raymond Roussel

by Tynan Kogane February 6, 2012

Not reading Roussel is similar to never having eaten a pomegranate: never having pulled apart the brittle skin, peeled back the bitter membrane, bit into each seed for a tiny squirt of juice, ending up with a red-stained shirt.

-

Dish, Dish: Gossiping with Joseph Epstein

by Margie Cook December 4, 2011

Epstein’s discerning eye for tantalizing details could have earned him a lucrative career as a gossip columnist in another life, but Gossip thrives on meatier substances.

-

Adam Foulds: The Incurable Poet

by Malcolm Forbes November 23, 2011

At one juncture we are told, or warned, that ‘the world abrades your finesse away.’

-

Mark Making: Sketches for Consequentiality

by Sara Christoph November 14, 2011

John Berger begins with one seemingly simple question: “Where does the impulse to draw something begin?”

-

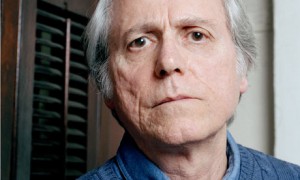

Here To Be Interesting: Don DeLillo’s The Angel Esmeralda

by Ben Clague October 23, 2011

Writers known for a certain tone and style often struggle to pull off anything outside their box, the literary equivalent of typecast actors.

-

What’s Past is Poetry: The Reaches and Limits of Glyn Maxwell

by Daniel Evans Pritchard October 10, 2011

For Maxwell, the past is a single fixed point, discontinuous from the present, and the center around which his imagination revolves, like a talisman or a totem.

-

Florida Gospel Fiction: Gospel of Anarchy and Swamplandia!

by Schuyler Velasco October 4, 2011

That’s the thing about Florida: in the best scenario, it wouldn’t have people in it. The Florida I loved as a child, the one that I still love as an adult, exists uneasily alongside human beings.

-

The Very Best Kind: On Lionel Trilling

by Morten Høi Jensen October 1, 2011

This is roughly what he meant by liberalism: it is, or ought to be, an acknowledgment of complexity and difficulty and an awareness of the objections that can be raised against it.

-