-

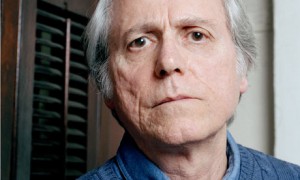

Here To Be Interesting: Don DeLillo’s The Angel Esmeralda

by Ben Clague October 23, 2011

The Angel Esmeralda

by Don DeLillo

Scribner, 2011Don DeLillo has two modes of operation: there are the major works, novels like Underworld and Libra and Falling Man, books that portend to deal with massive subjects like the last half of the American Century, the Lee Harvey Oswald and the JFK assassinations, and the attacks on 9/11 (in these novels readers encounter J. Edgar Hoover, Oswald himself, and a 9/11 hijacker, for instance). Then there are the works like White Noise and Mao II — no less major in stature, or skill — that operate on a more personal level, full of half-hidden people, go-nowhere conversations, inexplicable motivations and inexplicable actions, and repeated denials of information the reader desperately craves. Though DeLillo has been granted his Great American Writer membership based on books like Underworld — not that this is an erroneous membership — it is in the latter mode that his works take on a detail-level nuance and accuracy that leave readers unsettled and perturbed. The Angel Esmeralda, which is not a book of new short stories but rather a collection of some of his works that have been published in the past (the sole exception is “The Starveling,” appearing in this fall’s issue of Granta), is a sort of reader’s digest of this latter DeLillo mode.

DeLillo’s prose is often infectious, perhaps a product of the years he spent working for an ad agency, and his words often get caught in one’s head in the same manner effective TV jingles do. He works on a level of repetition with a few catchy phrases. After reading White Noise, for example, one might wander around for days on end spinning variations on the oft-repeated phrase, “That is what Babette is for.” There is a neurotic quality to the prose itself, like the mind of a person who simply cannot stop thinking. Similarly, DeLillo’s characters are scab-pickers, endlessly scratching at their wounds because it entertains them and because it passes the time. They role-play dialogue with others and themselves. In “Midnight in Dostoevsky,” two college students wander about a rural town, bantering to pass the time. They argue about the type of coat worn by the old man with whom they’ve become obsessed: “‘Duffel coat.’ ‘There’s duffel bag.’ ‘There’s duffel coat.’” The narrator describes their roundabout conversations as if they were descendants of Vladamir and Estragon: “we…walked on, talking about nothing much but making something of it.” In some sense, the same can be said for almost everyone populating The Angel Esmeralda. Conversation is something to do, a play to be acted out which passes the time and fills the quiet space, quiet space which otherwise must be filled with far more painful, internal scab-picking, something to which most of the characters seem deeply averse.

This internal scab-picking manifests itself in a deeply scrutinizing self-awareness, and the pickers themselves are often people with a lot of time on their hands, time to worry, time to provoke themselves, time to meditate on their actions and thoughts. In “Baader-Meinhof” a woman finds herself at a museum, looking for the third day in a row at a series of paintings depicting the jailing and death of the titular terrorists — almost like a premise for a parody of some unwritten DeLillo novel — when a man enters the room and begins a conversation with her. When the woman hears herself speaking in a language not entirely her own, she analyzes herself: “She wanted to be annoyed but felt instead a vague chagrin. It wasn’t like her to use this term — the state — in the ironclad context of supreme public power. This was not her vocabulary.” This wasn’t her vocabulary — she wasn’t being herself. She was using the words of someone else. This conflict is at the center of much of DeLillo’s work — people who have a rigorously defined image of themselves witnessing, powerless, almost as if undergoing an out-of-body experience, a strange departure from that image. Indeed, for reasons never entirely clear the woman won’t even tell the man her job — or previous job — as he prods her. When they continue their conversation in the museum cafeteria, the man plays the familiar part of the conversation pantomime as he talks about the half of his self not present, the part attending job interviews faithfully: “That’s another world, where I fix my tie and walk in and tell them who I am.’ He paused a moment, then looked at her. “‘You’re supposed to say, ‘Who are you?”” The man knows how conversation is supposed to flow, not personally but structurally. He speaks to her not to gain knowledge about her or because he is riveted by the facts of her life. He speaks to her because he is aware that people are supposed to converse in order to create tension and drama and intrigue, as though he is playing out in real life a scene from a TV show or movie. Indeed, this influence of fictional structure informs DeLillo’s characters; they are constantly sketching themselves. Just as the woman notes that “the state” is not a part of her vocabulary, so the man notes, “‘I don’t try to control people. That is not me.’” But of course he says this while trying to get the woman to undress, and when instead she hides in her bathroom he masturbates on her bed. In the end, he apologizes, his voice a different tone, his words from a new lexicon. His mask slips to reveal the other, forgotten half of himself.

The idea of the mask resurfaces throughout The Angel Esmeralda. In the opening story, “Creation”, an unnamed man and his wife are stranded in the tropics, unable for a time to get a flight back to New York. They share a taxi to and from the airport with a German woman, Christa. When a seat on a plane finally opens up, the man insists his wife take it while he remains in the tropics. Then, without the slightest note of guilt or worry, without even acknowledging his actions, he slips on his mask: “[Christa and I] went to the same hotel and I asked for a pool suite. We followed a maid along the beach and then up the path to one of the garden gates. The way Christa reacted to the garden and pool, I realized she’d spent the previous night in one of the beach units, which were ordinary.” It’s not as though he’s cheating, or thinking of cheating — it’s as though the unnamed man is still married, it’s just that his wife is Christa. He books a suite for them together without asking, without wondering if she’d accept. The prose is totally devoid of apprehension, fear, and awareness of consequence. He is not himself. He is a different version of himself, and the woman in his life is not his wife — she has disappeared down some portal — but this German woman. For the rest of the story he has only his relationship with Christa, full of conversation that staves off questions about his first and primary woman. The unnamed man sketches out Christa’s character in conversation, saying “You have a desire to go unnoticed,” and “You want to be indistinct. I see this in different ways. Clothes, walk, posture.”

Like the college students in “Midnight in Dostoevsky” who follow around the old man with whom they’ve become obsessed, carving out a past for him, a history, family members, reasons for appearing now in this college town, so the unnamed man in “Creation” creates a character based on Christa, full of his own conjectures and wishes. DeLillo’s characters are insatiable, knowledge-hungry people, and if they don’t know someone’s story they are just as content to invent one — sometimes they even prefer it. Of course, they often do this while pretending to be somebody else themselves. In fact, most stories in this collection take place only when the mask is on, perhaps bookended slightly — in the case of “Creation” for example — by moments of what we might consider a more genuine state, though the question must be posed: if The Angel Esmeralda is full of masked characters creating characters out of the people they interact with, how can we accept anyone’s identity as authentic? If everyone is always playing roles themselves and crafting roles for each other within the stories, wouldn’t it imply that before and after the stories, too, these characters are continuing with their games?

Multiple characters in the collection seem distinctly aware of the presence of theatre in our lives — they prompt other players for lines, inform others who they’ll be playing, manipulate conversations and scenes as though they are not actual conversations but ones taking place on a stage. In “Hammer and Sickle” an imprisoned white collar criminal watches his young daughters as anchors of a children’s news show on television, reading reports about the world markets and financial collapse written by their mother. Day by day the population of criminals watching the news show grows, until, when nearly everyone in the prison is watching, the girls dramatically read off the names of Marxist and communist leaders and thinkers, the criminals — many in for massive financial fraud — delirious and raving in the aisles, a revolution come to jail. But when the moment ends in anti-climax, with one of the daughters simply staring into the camera for a long time, the prisoners come to their senses and filter out quietly, disappointed playgoers shamed of their momentary excitement. Incidentally, it is in this prison where masks seem to be the least use. The narrator tells all aspects of his life to his cellmate. Prisoners tell one another openly of their crimes. The narrator’s cellmate says, when the narrator claims the details of his imprisonment aren’t interesting, “We’re not here to be interesting.” And this, perhaps, might explain the behavior of those outside prison. They want to feel interesting — but they’re not — and they want to have interesting conversations — but they don’t. So they create artificial characters, both in themselves and others, and play out conversations they’ve seen on stage, in film, on the television, conversations that lead in those instances to interesting things. Thus that in “Baader-Meinhof” where the man points out the woman is missing her lines; Thus the importance of a believable and detailed backstory of the mysterious man in “Midnight in Dostoevsky”; and thus the adultery in the Caribbean in “Creation” — what’s more interesting than a brief affair with a foreigner after you’ve sent your wife on your way? From what could one extract more drama, drama necessary to be interesting?

Not every story in The Angel Esmeralda, of course, fits the pattern, and for those well-versed in DeLillo’s work these might be the more interesting pieces. The titular story, about the death of a young girl in the bombed-out South Bronx and her apparent reappearance as a face on a Minute Maid billboard, reads at times like DeLillo trying to write like someone else. The amount of space spent on physical description, the fullness of the two nuns steering most of the story, the absence of consumerism and technology, all add up to a puzzling piece. There are long, meticulously crafted, eloquent passages evoking the desolate apocalyptic spaces of the South Bronx and clumsy interior monologues, which gives the story an uneven flow, leaving the reader with many individual sentences worthy of rereading a hundred times but a story that’s probably not worth looking at again. Then there is one of his earlier pieces, “Human Moments in World War III,” a story about two astronauts in space which bears all the hallmarks of DeLillo’s work (nuclear war, space, distant people, odd transformations of character, etc.) — but that, for some reason, simply doesn’t work, feels too far removed, as though the story is the earth and readers are the astronauts, floating helplessly, able to see but unable to connect.

Writers known for a certain tone and style often struggle to pull off anything outside their box, the literary equivalent of typecast actors. If The Angel Esmeralda contributes anything of deep significance to DeLillo’s career, it is the confirmation that he is one of these writers. Fortunately, his tone and style are so distinct, so memorable, so in step with the life of a more-or-less average American in the age of consumerism and overwhelming modernity that this confirmation does very little — if anything — to hamper opinion of DeLillo. The Angel Esmeralda is not an essential book, holds no key to all of DeLillo’s often-mystifying novels, offers, in fact, nearly nothing readers haven’t seen before. But the qualities of his fiction and its resonance to our experiences in the supermarket, or while watching airborne toxic events, or deep into an artificial conversation, combined with the fact that these stories are not new but still sport a sheen of vitality frequently lacking from contemporary works, more than makes up for what is essentially a collection of DeLillo’s greatest hits.