-

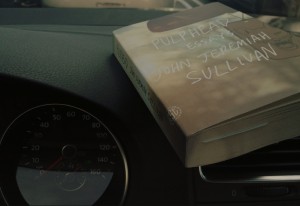

John Jeremiah Sullivan’s Pulphead

by Robert Carver February 21, 2012

Pulphead

by John Jeremiah Sullivan

Macmillon, 2011Consider for a moment that fate conspires to make you into something particular. A race car driver, perhaps, or a Senator. At what point would you know — in that deep down, in-the-bones sort of way — that this thing that you do, that you worked so hard to become, dreamed about, sacrificed for, actually has the backing of the string-tugging, door-opening cosmos?

I’m only guessing, but I’d like to think that for John Jeremiah Sullivan, Southern Editor of the Paris Review, writer for Harpers, GQ, and Oxford American, and author of the recently released collection of essays Pulphead, that moment came when he and his wife purchased a neo-colonial home in Wilmington, South Carolina, the home previously used to film portions of the television show One Tree Hill. The home at which a producer of the show came knocking, asking Sullivan for compensated permission to use the house once again. Consider: a man who makes his living through a well-trained eye on pop culture (essays on the likes of Axl Rose, The Real World and Michael Jackson take up over half of Pulphead) miraculously ends up leasing his house to a teen melodrama? It’s the writerly equivalent of the dove landing on Jesus’s shoulder.

I belabor the point, but it’s as if someone walked up to Sammie Sosa and handed him a metal bat, just to see how far that damn ball could fly. In the resulting essay, “Peyton’s Place,” which first appeared in GQ and closes Pulphead, Sullivan retells this experience as one recalling details of an ill-advised affair. First, there was the seduction: the producers offered compensation equal to the amount of the mortgage. Then, there were the lavishing of gifts and the novelty of something new: the show decorated the house, and introducing family members to TV stars had its appeal. And, of course, there were boundaries: the show would not film beyond the first two rooms. Of course.

The affair sours. The show becomes needy, invasive; shipped off to the Hilton, the Sullivans watch episodes filmed in rooms of their home supposedly off limits. Whereas before the work crew had been careful not to leave a trace of evidence after shooting, they began, like lipstick left on a collar, to make mistakes. In the end, things even turned violent with the introduction of a new character, a sociopath, whose explosive role leaves tell-tale bruises on the house. It’s a thoroughly entertaining, intimate, and disturbing look at the strange concessions we make at the intersection between fantasy and reality, the boundary of which is not entirely clear:

We formed memories of our house that weren’t memories; we’d experienced them solely through television. We hadn’t been there for them, yet they’d occurred while we lived there. It felt something like what I imagine amnesiacs feel when they are shown pictures from their unremembered lives. You thought, How could I not remember this, how can I not have known that this happened? Coming back after a big shoot, and finding everything just as you’d left it, despite your certain knowledge that dramatic and often violent things had occurred there while you were gone, it kept bringing to mind a Steven Wright joke, from one of his comedy specials in the eighties. “Thieves broke into my house,” he said. “They took all my things and replaced them with exact replicas.”

“Peyton’s Place” is a fitting close to this collection of fourteen essays, topically disparate yet thematically bound: Sullivan prods the odd boundaries of Americana, focusing on both the common and the unknown from angles few would think to frame. Sullivan goes to a Christian Rock festival, and spends a single paragraph discussing the music — coincidentally the best critique of a genre I’ve read. The entirety of his Axl Rose essay centers around his inability to get an interview with the musician: “his people wanted Axl on the cover,” Sullivan told me at a book signing, “but he isn’t looking so good these days.” To discuss MTV’s The Real World, he follows cast members who have been off the show for years. He recovers the South through forgotten history, profiling Native American cave paintings in Tennessee, a near-forgotten botanist from the turn of the century, and lost lyrics in a pre-war blues songs. In each, one gets the distinct impression often rendered by the best essayists: Sullivan is writing exactly what he wishes to write, in the way he wishes to write it, regardless of his audience. “If you don’t know who [Bunny Wailer] is,” opens the essay “The Last Wailer,” “ — and of the people who read this, surely a goodly percentage won’t know.” Whether you know or not — or rather, care or not — by the time the end of the essay, you marvel.

Pulphead’s chief draw lies in Sullivan’s tendency to find topics for which there are few natives — and it can take a moment to find the lay of his land. Take, for example, the essay “Unknown Bards,” about the deep history of Southern Blues and the efforts to keep this history alive. Sullivan writes about music in the way Hemingway writes about wild animals, and his research is fanatically detailed: an attempt to decipher a garbled word, which sounds like boutonniere, in a pre-war southern blues song leads to a “1398 citation from Jon de Trevisa’s English translation of Bartholomeus Anlicus’s ca. 1240 Latin encyclopedia, De proprietatibus rerum (On the Order of Things): ‘The floure of the mele whan it is bultid and departed from the bran.’ Yet, I must confess: as someone completely disinterested in the origins of blues music, I read the first few pages on faith, patiently, a pinky tucked into the last page of the essay to gauge my progress in the same way a runner trains her eye on a distant telephone pole. Disinterested, that is, until I came upon this passage, in which Sullivan is reflecting on the song “Pour Mourner,” recorded in 1897:

When this song comes on I invariably flash on my great-grandmother Elizabeth Baynham, born in that same year, 1897. I touched that year. There is no degree of remove between me and it. […] Knowing that this song was part of the fabric of the world she came into lets me know I understand nothing about that period, that very end of the nineteenth century. We live in such constant nearness to the abyss of past time that the moment is endlessly sucked into. The Russian writer Viktor Shklovksy said that art exists ‘to make the stone stony.’ These recordings let us feel something of the timeyness of time, its sudden irrevocability.”

I flipped back to the beginning, and began to read again.

Each of Pulphead’s essays seem to have a moment like this. Whether you’re invested from word one, or slowly entering his waters, Sullivan slides in a point of epiphany that comes so unexpectedly, and yet so inevitably, that you sit there, stunned in both awe and (if you’re a writer yourself) jealousy. In part, this has to do with his extreme empathy, his ability to place himself, quivering, on that knife-edge between critical and receptive. After spending a few days with a group of tough-love Christians at a Christian rock festival, for example, Sullivan writes, “it may be the truest thing I will have written here: they were crazy, and they loved God — and I thought about the unimpeachable dignity of that, which I never was capable.” Sullivan casts out a line on your doubt, twitching and teasing his topic until it becomes alive; you lunge, and are hooked with one mighty pull.

There’s a question often raised in the non-fiction world about ‘truth’. James Frey betrayed it; Truman Capote padded it. Sullivan plays with it. One of the best moments in the collection comes when Sullivan is speaking with Miz, a former Real World cast member who makes his living patronizing bars and clubs:

I was like, “Mike” — that’s his real name — “doesn’t this lifestyle wear you down?”

He goes, “Yeah, but I take care of myself. First thing, dude: I don’t mix my drinks. If I’m drinking vodka, I keep with vodka. Shots make that hard, though. Somebody hands you a shot, it’s hard to be like, ‘Can I have something else?’ But for the most part…”

“But what about your soul?” I said. “Does it take a toll on your soul?” He looked down at his drink.

Psych! I didn’t ask him that.

Leaving alone the mimicking tone that Sullivan adopts in this piece — itself a stroke of mastery, and Sullivan’s shifting voice is rightly praised by James Wood — the genius of this moment is in how Sullivan uses an untruth on the page to expose the deeper truth of his profile’s reality. Sullivan doesn’t ask the question because, in part, Miz isn’t truly capable of answering it. Yet by allowing the question to exist on the page, tongue and cheek as it is, the stakes become real for the reader. It is perhaps no mistake that in an essay about fake reality, titled “Getting Down to What’s Real,” the most real moment is itself fake.

More risky is his essay “Violence of the Lambs,” in which, he admits at the end, “big parts of this piece I made up. I didn’t want to say that, but the editors are making me…” Beside the Wallace-onian nod to the callousness of editors to High Art, the whole essay is a bold exploration of the boundaries of what a non-fiction writer can get away with. In this disturbing essay about animals revolting against humanity, Sullivan made up characters, interviews, and an entire scene-heavy trip to Kenya. The facts, he maintains, are real, but their representation is pure theater. Is this a gross misuse of a reader’s trust? I don’t think so, partly because the mea culpa is part of the essay, and something about realizing one has been hoodwinked within an essay is far more entertaining than realizing so afterward (consider Franzen’s recent admission that David Foster Wallace made up some of the characters in A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never do Again. One cannot help, momentarily at least, feeling betrayed). But we’re entering shaky ground, here: is manufacturing a creative framework to convey factual information dishonest? Is it as dishonest as manufacturing factual information? Is Sullivan’s admission at the essay’s end the actual boundary between fiction and non-fiction? Is the justification in the feeling the reader is left with after discovering the façade?

John D’Agata was heavily criticized in his excellent meditation on personal and cultural suicide, About A Mountain, for the way in which he altered the timeline of events so that they would dramatically coincide. He, too, admitted his sleight of hand at the end of the book, going so far as to document every instance in which he combined characters, moved the timing of events, or conflated multiple trips into one. Yet for many it was not enough, and his book suffered for it. Sullivan will surely not take so hard a hit, since he raises these questions in one essay among many. That it is arguably the weakest of the essays suggests that it was a worthy risk, but one that failed to pay off.

The question for both D’Agata and Sullivan is: does the façade, and subsequent pulling back of the curtain, work? That is to say: does the non-fiction writer gain more currency by not only co-opting the methods of fiction, as any good writer does, but the content, provided such content is revealed as fiction? Does contrivance of this manner subvert truth, or support it? Though many will disagree with me, I’m inclined to say that, in the examples above, Sullivan and D’Agata earn their manipulations, if only by virtue of their disclosure — but the value is in the disclosure, because only then is the author artfully inviting us to debate the artifice of written truth and the merits of its manipulation (the question remains whether the editors actually forced the hand; if the writers truly wished their forgery to remain undisclosed: what then?). Far more disconcerting, therefor, is a recent Amazon review of Sullivan’s essay on French naturalist C. S. Rafinesque, “La•Hwi•Ne•Ski: Career of an Eccentric Naturalist,” which first appeared in Ecotone in 2008. The review is by Charles Bowe, whom Sullivan references in the essay as “the foremost scholar of Rafinesque’s works”:

If that is so, I herewith declare that in his Rafinesque chapter Mr. Sullivan has attained a new world record for making the greatest number of gratuitous errors yet to appear in print about that largely misunderstood nineteenth-century polymath. If this embarrassing farrago is for the sake of what has been called Mr. Sullivan’s “laidback, erudite Southern charm,” may Heaven preserve the South from the further infliction of such half-baked erudition.

If Mr. Sullivan invents quotations to put into the mouths of others as he does in his Rafinesque chapter, if he confuses the chronology of events as he does there, if he discourses on books he clearly has never read as he does there, if he narrates interchanges between people for which there is absolutely no evidence that such relationships ever existed as he does there — if these egregious faults characterize the other chapters as they do this one, then the book is a shameful disgrace and should never have had Time Magazine‘s accolade as a “Top 10 Nonfiction book of 2011.”

Creative non-fiction: regardless of where one stands on the debate of which of those two modifiers rules the other — and to what degree — for everyone, there is a line. Few, if any, essayists would satisfy the historian of whose specialty they’ve stumbled upon, but Bowe’s condemnation is particularly striking. Sullivan did not just get things wrong, Bowe suggests, he willfully fabricated. And there is no Psych! tagged onto the essay’s end.

These are questions at the boundaries of non-fiction; questions for writers like D’Agata and Sullivan, who push to fine-tune our awareness and define the role of the contemporary essayist, and for readers, critics and historians who debate whether those pushes are justified. Perhaps what it comes down to is trust: do we believe the writer is seeking, perhaps stumbling, to find the best possible way to convey a deeper truth to us? Or is he, a la Frey, just trying to make a buck? Is there room for such subjectivity in non-fiction? I don’t know. But after reading Pulphead, I will follow Sullivan down any rabbit trail he chooses to venture. I just might drop bread crumbs behind me as I do.