-

Laila Pedro

-

Be (In) Here Now

by Laila Pedro April 8, 2013

From the first moment of seeing Harlan’s Cave through the glass, certainty evaporates.

-

Becoming Comrades

by Laila Pedro July 8, 2011

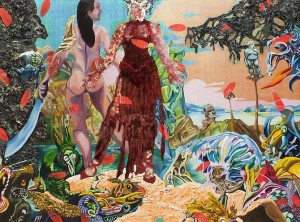

“Migration” is interesting less for its nomadic creators or themes than for its focus on the perceptual refractions of the physical, often-feminine and unstable body.

-

Sheer Proximity: Chris Kraus’s Where Art Belongs

by Laila Pedro April 5, 2011

For all its faults, Kraus argues, the “art world remains the last frontier for the desire to live differently.” The claim is ambitious.

-

Sitting in a Tree: Me & the Artworld at EFA

by Laila Pedro February 9, 2011

There is a wide range of depth and quality in this show, interesting for the prevalence of two kinds of fin-de-siècle themes: one, an obsessive kind of cataloguing reminiscent of the 19th century Decadents; the other a knowing, overly personal, faux-folksy, quasi-naïf intimacy that recalls the end of the more recent century.

-

Toujours Tout-monde: For Édouard Glissant

by Laila Pedro February 5, 2011

The obituaries, one feels, are all wrong. As though the death notice of one so avidly alive could be anything but. “Caribbean militant”, “Martiniquan writer.” I suppose he is those things, journalistic shorthand for a man who explained to us, its makers, just what the world could be.

-

Sculpting the Text: So Many Words at ZieherSmith

by Laila Pedro January 24, 2011

The exhibition succeeds on many levels, though too often it’s maddeningly difficult to decipher how many of these successes are intentional, despite Hart’s wordy description. It’s beautifully arranged, with a consistent logic that prizes thoughtful details and careful spatial pacing. Hart is canny enough, for instance, to have our first encounter be Allen Ruppersberg’s “thank you, mr. duchamp. would you close the door please? thank you.” which is affixed to the wall in such a way that you do, in fact, have to open it. It’s the kind of hands-on, witty engagement with the audience that made this period of sculpture so engaging.

-

E pluribus unum? Of many one at Scaramouche

by Laila Pedro November 29, 2010

If space and depth are displaced (or misplaced) in Diernberger’s work, in Rehana Zaman’s Diagram of an Event, the time, as Hamlet said and Deleuze echoed, is out of joint. A diagram of time, reducing four dimensions to the representational two, destabilizes itself, undoing its own order and rationality even as its mode of communication is implicitly described as an attempt to impose order and rationality. It’s an impossible diagram of the intangible.

-

Relational Affectives: “Geography” at the Rooster Gallery

by Laila Pedro November 3, 2010

This is complemented by the diversity of genre and medium, both between the works and within them. Carlos Roque’s digital print Mundo Moderno no. 2 is a good example of this confluence: a jumble of precise, draftsman-like drawing, overlaid with varieties of text—graffiti-style, signage, and so forth—presented in both anterior and mirror image, so you’re never quite sure of how deep the work wants to take you, dimensionally speaking. Sharp lines thrusting at various angles through the frame, and variously scaled vehicles add a dimension of movement, and thus, also, of time, to the assemblage of directions.

-

Physical History: The Mexican Suitcase at ICP

by Laila Pedro October 15, 2010

Here there are at least twenty negatives dedicated to a couple lunching in a plaza—with the woman out of the frame. The minute changes in the man’s facial expressions tell a complex story. Each negative could have yielded a different set of photos with its own physical life and a very different narrative. Very rarely does one take so many shots on the digital camera—the physical experience of clicking away, unaware of what shows up until the film is developed, has nearly ceased to exist, and we feel its loss here. One wonders which image the photographer would have chosen as the “right” one, the singular, defining image, had the photo’s journey not become a Borgesian garden of forking paths.

-

Auto Biography: Bernhard Fuchs at Jack Hanley

by Laila Pedro September 27, 2010

In pictures like Weißer Fiat-Bus (White Fiat Van), and Grüner VW-Transporte there is a regrettable surfeit of what I always think of as ‘serious-memory-light,’ a sort of aggressively mellow, late-afternoon-inflected, golden tone that is just desperate to be described as “evocative” but comes across as intensely maudlin. This sentimentalizing tendency is evident in other heavy-handed touches: the repeated use of a grey-on-grey theme, the mists, the path-heading-into-mysterious-woods motif, the way the gaze lingers on the beginnings of rust around a window frame.

-