-

Toujours Tout-monde: For Édouard Glissant

by Laila Pedro February 5, 2011

Ce sage marin, mesuré diseur…Il vient, enfant, dans le premier matin. Il voit l’écume originelle, la première suée de sel. L’Histoire qui attend.

(This wise man of the sea, measured teller of tales. He comes, a child on the first morning. He sees the primeval foam, the first sweat of salt. History, waiting).

- Édouard Glissant, Le Sel noir.

Of which Glissant do we speak? He was irreducible in person—a force of nature who spoke barely above a whisper. In death, —“scattered among a hundred cities”— how do we write about him? How do we write about the extreme, pitiless generosity of his vision, which respected the world too much to condescend to it? Glissant knew he was a genius as surely as we knew him to be. This is no paean to the simple man behind the novelist of La Lézarde, the playwright of Monsieur Toussaint and Le Monde Incrée, the world-expanding theorist of Poétique de la relation. There was nothing simple about him.

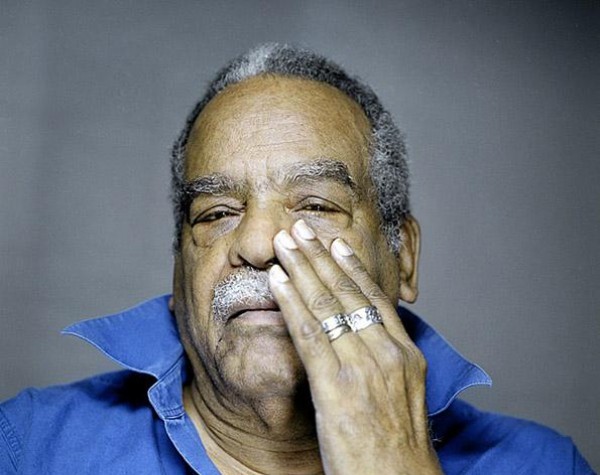

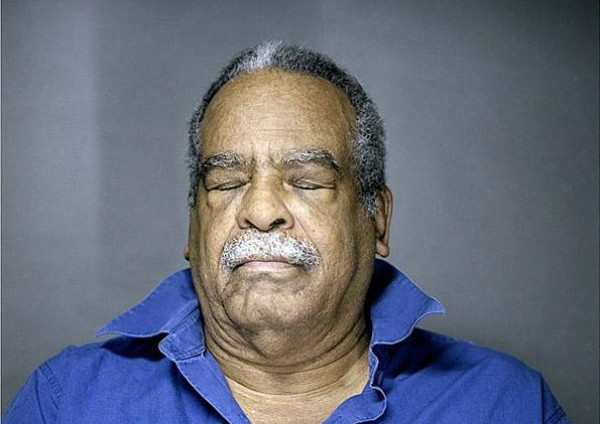

Should I write, then, about our own experience of the poet, intimate and local? About the Monsieur Glissant who every Friday received a group of students in his living room, listened to our poetry (his attention had a bright, hyper-focused quality: never frenetic it was rather piercing and enervating and unmatched), talked to us—incredibly!– like poets? The man who, in his old age, with his carefully-measured glass of red wine (never anything so pretentious or precious as the fashionable biologique) in one big hand, the other resting, more often than not, on his cane as he teased the promising syllables from our efforts? These we had brought, quaking with elation and laughing, sometimes, at the serendipity of this surreal dialogue with someone who might so easily seem beyond our reach. The one who saw through us, eyes half-closed, and offered no indulgence for our self-deprecation, no quarter for our dissimulation, only infinite patience. Ought I to write about the moments when, in gleeful anticipation of a coming trip, he would sing to us, “Martinique, c’est très chic.”? Or about the afternoon when we were joined by the young, brilliant Haitian poets he welcomed after the earthquake, who read to us poems written on airplanes rising above the ruins of Port au Prince? Or perhaps I can write about the phrases that could only come from him, illuminating a work in one sentence: C’est une poésie de la fulguration. More simply, I can say: we became poets because he believed us to be. To receive his attention was daunting, a profound challenge; the Martiniquan writer Raphaël Confiant wrote, for years, almost in spite of Glissant:

j’avais avoué avoir lu, à l’âge de 18 ans, trois pages de son fameux roman «La Lézarde» … et avoir refermé immédiatement l’ouvrage pour ne le rouvrir qu’à l’âge de trente ans. Pourquoi? Parce que j’y avais découverte une écriture si puissante que je m’étais dis que si jamais je m’y enfonçais, si je continuais à lire l’ouvrage, jamais je ne pourrais devenir écrivain à mon tour.

(I told him I had read three pages of his famous novel La Lézarde at the age of 18…and closed the book immediately, not to open it again until I was thirty. Why? Because I had discovered in it writing so powerful that I told myself if I ever sank into it, if I continued to read the work, I would never be able to become a writer in my own right)

It’s been hardly forty-eight hours since Édouard Glissant died. His death was not unexpected, but it was uncharacteristic. On the Internet, a torrent of homage whose eloquence and polish bespeak his long illness as much as the caliber of writers he influenced (Bernabé, Chamoiseau, Confiant and on and on); a generation now facing the tremendous, electrically charged responsibility of carrying on his work. It was not unexpected. Writing, we prepared for what we knew was not possible.

We must not protect his legacy—protection is not something he would abide. We do not honor him by enshrining his work in rigid interpretations, but by throwing it open, wide to the world. We honor Glissant by reading his work and by sharing it.

Any number of platitudes—which, one imagines, he would have swiftly dismissed with a « Ne dites pas de bêtises.» —seem inevitably to follow a death of such significance. « He changed everything in my life, forever », we, his students, have said to each other, with no twinge of hyperbole. « I feel like my heart is gone ». A former student: “A library has burned down.” To look beyond platitude is to look for the intimacy in the universals he interpreted, the most intimate made the most universal. One woman, his student and friend, will dig out a fire pit and burn a dead tree in her frozen back yard on Staten Island, and in the scent of pine needles, in the showering sparks, read his words to the frigid winds. I, trying to read Auden’s elegy for Yeats at the suggestion of an understanding friend, am myself frozen by the words “He became his admirers.” My late uncle, a playwright, refused to leave his native Havana, even in appalling economic circumstances—the most intimately local, he insisted, was the only setting for human work. The only work, in other words, worth doing.

To root him (with no disregard of his preference for the rhizome) in his hyper-local universality, we would think of the young man, the son of a plantation laborer born in 1928 in Martinique, formed in the lycée system. The world of the Antilles– their history, yes, but also their sights and smells and sounds, permeate his writing, his thinking. The words he would later write about Saint-John Perse (Saint-John Perse et les Antillais) are as readily applicable to himself:

L’Ilet-les-Feuilles. Mer et forêt. Cette nature qui enjendre et régente le style…Voies toujours ventées: l’en aller, le maigre, le fluide, la Mer. En même temps, une démesure architecturée, des pourrissements végétaux, des lumières de sel accrochées aux racines violettes…La nature parle d’abord en nous.

(L’Ilet-les-Feuilles. Sea and forest. That nature, which gives birth to style and rules it. Always-windy paths: the departing, the meager, the fluid, the Sea. At the same time, a crafted excess, vegetal putrefactions, salt lights hanging from violet roots. Nature speaks first within us.)

Nature– the violently fecund nature of the Caribbean, alternately crashing and delicate — always spoke in his poetry, in his plays and in his theoretical writings. And it was this ineluctable attention to the crucible of the new world, his certainty in the value of that unique and multiple experience, that gave so many literary voices– from Guadeloupe and Martinique and Haiti, but also from every corner of the globe– the conviction to assert their own subjectivity, the courage to take their place in the tout-monde he envisioned, and the implements to enter, as they were already entered, into relation with the wide world.

He arrived at the Sorbonne in 1946 (itself no small feat), plunging into philosophy and ethnology and the myriad circles and colloques devoted to discussing poetry and culture and writing — all set against the increasing urgency of securing independence for the colonies. He was the friend of painters and writers and politicians, the interlocutor—and frequent, eloquent critic—of Césaire and Fanon. (At our first meeting, on learning I was Cuban, he informed me, with a sly gleam in his eye, that he had had many conversations with Fidel Castro. Later he would tell me about his friendships with Wifredo Lam and Nancy Morejón). He worked ceaselessly in those years (as he would until it was no longer physically possible), agitating for the right of the colonies to self determination, and writing, always writing.

In some of his earlier poetry we see the architecture of a life’s work. In Le sel noir, we find an odyssey of wandering unfettered by natural or temporal limits– salt and foam, Carthage and African storytellers, metered by the mutable, inexorable sea. Les Indes (The Indies), whose poetic density surpasses the lyrical, is an epic of 1492, its eloquent genesis. Its six cantos, L’Appel, Le Voyage, La Conquête, La Traite, Les heros, Relation, (The Call, The Voyage, The Conquest, The Trade, The Hero, Relation) shaping the Antilles even as they trace their history in verse. In the holds of the slave ships, in the bodies scattered across the bottom of the ocean from Africa to Europe to the Americas, in the eyes of the conquerors, in the harrowing poetics of encounter, Glissant shows us the new world. Les Indes is Glissant’s entry into the pantheon of epic poetry, but it is also in a very direct, very specific dialogue with another poem of genesis, this one Guadeloupean — Perse’s Vents (Winds) from 1946 about whom Glissant wrote voluminously. Writing which bespeaks his generosity, his admiration for admiration. Perse, the Berber novelist and playwright and independence hero Kateb Yacine: in these Glissant heard the murmurings of the chaos-monde. His was a lifelong battle against the homogenous, against globalization-as-standardization. He taught us not to read things (cultures, people, poems) in such a way as to translate them, violently, into our own image, but instead to honor their incomprehensibility and mystery. He was opacity’s great defender, the staunch opponent of imposed explanation and weaponized transparency.

Only the biggest questions of poetry– the movements of humanity across oceans and time—are constant of Glissant’s work. Yet it was his novel La Lézarde (The Ripening) that won him the Prix Renaudot in 1958. Because of his organizing on behalf of colonized peoples, and particularly his vocal sympathies with the Algerian independence movement, de Gaulle forbade Glissant from leaving France for six years. In 1965 he returned to Martinique, using the funds from his Renaudot to establish l’Institut martiniquais d’études and the journal Acoma. Acoma is a tree that grows in Martinique, notable for the fact that a new tree will grow from its bisected trunk (this summer, after his heart attack, we leaned on this image).

He would live over the years in Paris, Baton Rouge and New York, always engaged, always seeming somehow more alive than the rest of us. In his theoretical writings (L’intention poétique, Poétique de la relation, Discours antillais, Introduction à une poétique du divers and on) he parsed poetry, never explaining, always deepening. Poetry was revelatory when Glissant read it. He revealed networks of encounter, a tout-monde (an all-world) of constant openings, what he called a pensée archipélique– a philosophy inflected by the multiplicity of the archipelago rather than by the totalizing continent.

The obituaries, one feels, are all wrong. As though the death notice of one so avidly alive could be anything but. “Caribbean militant”, “Martiniquan writer.” I suppose he is those things, journalistic shorthand for a man who explained to us, its makers, just what the world could be. Here is Professor Glissant, in Louisiana, finding again his plantation cosmologies, putting America in context for us, writing Faulkner, Mississippi. In 2007, the seminal manifesto Pour une littérature monde, of which he was a signatory with other luminaries like Tahar Ben Jalloun, An anda Devi, Maryse Condé. Later, a Distinguished Professor of French at the CUNY Graduate Center, writing with Patrick Chamoiseau L’intraitable beauté du monde, (The Intractable Beauty of the World) his address to Barack Obama, the first métis President, reminding us of his election’s significance. He knew the necessity of his voice.

To the students and poets and thinkers and writers he touched now falls the responsibility of carrying on his work, of living in the world he opened to us. In the coming days, francophone radio and press will dedicate programs to him, to discussing the poet, the playwright, the novelist, the political thinker, the literary philosopher. Those of us who had the astonishingly rare privilege of knowing him, who, by luck or chance or obsession were brought into his orbit, will find comfort in remembering him as Confiant does:

Chaque soir, ce dispendieux, cet homme au grand cœur, tenait table ouverte, dans sa maison située au bord d’un lac et nous, les participants au colloque, l’entourions comme s’il avait parole d’oracle.

(Every evening, this expansive, this great-hearted man, would welcome us to his table, in his house at a lake’s edge, and we, participants in the symposium, would surround him as though he spoke the words of the oracle.”)

1 Comment

Remembering Glissant « poumon de papillon

[...] http://idiommag.com/2011/02/toujours-tout-monde-for-edouard-glissant/ [...]