-

Sculpting the Text: So Many Words at ZieherSmith

by Laila Pedro January 24, 2011

This past December, T.J. Clark, writing about a major Cézanne exhibition at the Courtauld Gallery for the London Review of Books, started out with a rather sensational claim: “Cézanne, whose work was the touchstone for critical thinking and writing on art for more than a century, cannot be written about any more.” The qualities we recognize and respond to in Cézanne are, he writes, “remote from the temper of our times.” Despite the bombastic beginning, Mr. Clark is certainly too wily to devote an entire piece on Cézanne to not writing about Cézanne, and in fact goes on to praise him to the skies, even as he maintains that such praise is anachronistic.

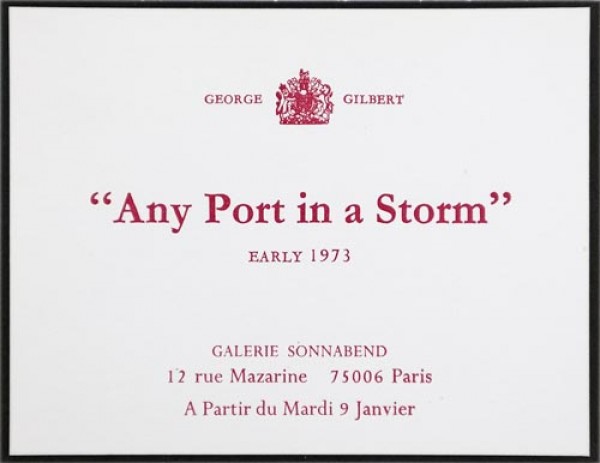

I was reminded of the possible impossibility of re-reading/writing the giants of the twentieth century by the ZieherSmith gallery’s exhibition Sculpture in So Many Words: Text Pieces 1960-75. The exhibition, as we are proudly informed, is “curated by Dakin Hart.” Leaving aside any issues raised by the current popularity of “curated”as a verb (not to mention “curated by”, which passive-voices the work into a bizarre state of submission), its intention is quite interesting. The press release uses a lot of words to inform us that, essentially, the ephemera around sculpture, what usually operates in the wings of the public’s interaction with the work, such as artist’s announcements for performances, newspaper ads and the like, are being shifted to center stage. There is a certain wariness accompanying the archived marginalia of the conceptual. How many times can we keep shifting the frame before the exercise becomes institutionalized in precisely what it seeks to transcend? In many ways (and this is hardly original) the vanguard impulse stops “working” the minute it’s put into a museum, re-interpreted, or in any other way situated.

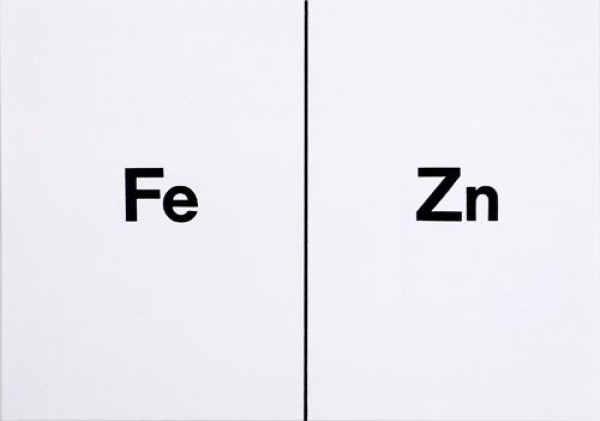

The particular issue of situating this work– of fixing it in time and space– is a defining problem of Sculpture in So Many Words. Hart, in fact, locates it very precisely (or not at all, depending on your perspective) as tracing “one important, largely unrecognized route by which Duchampian conceptualism and Cageian time-based process theory coalesced into the practices that constitute much of contemporary art.” It locates contemporary notions of sculpture– and of what sculpture can be– at this particular point of contact (affinity? affiliation?), which, really, is the only way the exhibition can make sense. But is it necessary as an art show, rather than as part of a museum collection? I remain unconvinced. So Many Words exists in an uneasy twilight between the curatorial and creative that seems to create as many problems as it opens possibilities. Hart’s exhibition reflects the give-and-take, on-the-one-hand-but-then-again spirit of Dadaism reworked in ’60′s and ’70′s conceptual sculpture, but does so in a way that highlights its characteristic evasion of meaning in a negative sense. We are left with confusion rather than with the visceral impact that made these works speak (or that made the words work) despite, and because of, the extremity of their abstraction, their rejection of genre. This is the show’s chief source of frustration and interest.

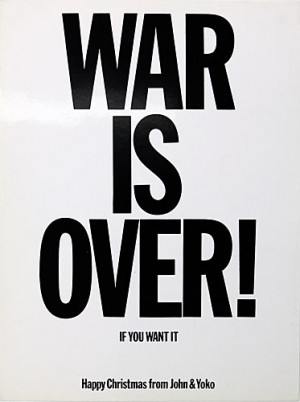

The exhibition succeeds on many levels, though too often it’s maddeningly difficult to decipher how many of these successes are intentional, despite Hart’s wordy description. It’s beautifully arranged, with a consistent logic that prizes thoughtful details and careful spatial pacing. Hart is canny enough, for instance, to have our first encounter be Allen Ruppersberg’s “thank you, mr. duchamp. would you close the door please? thank you.” affixed to the wall in such a way that you do, in fact, have to open it. It’s the kind of hands-on, witty engagement with the audience that made this period of sculpture so engaging. What’s more, having Duchamp explicitly acknowledged from the outset, verbally and through physical experience, though an obvious choice, is still a necessary and intelligent one, showing a self-awareness that warms us to the rest of the show. Fred Sandback’s Conceptual Constructions, simple lines on white paper with declarations like “There exists a sculpture consisting of all patterns of light on retinal surfaces occasioned by the existence of this statement, and of nothing else” are great fun, in the best spirit of cerebral, syntactic games of text and medium. Yoko Ono is well represented by her iconic War is Over if You Want It Christmas card as well as by less ubiquitous, equally engaging works like Light Piece from Grapefruit. The satisfaction, derives from seeing important work and its accompanying ephemera, more than from any essential or edifying re-framing accomplished by presenting these as text sculptures. The centrality of that potentially rich tension is never really clear beyond the Ruppersberg.

Hart’s successes, then, are as much art-historical ones as they are any groundbreaking re-working of curatorial practice. An interest in sculpture, particularly “conceptual sculpture”, often connotes a certain fetish for the object. It becomes, at bottom, about things filling space with an interesting, moving, or otherwise engaging presence. In that sense, intentionally or not, the exhibition succeeds (and how sad, though of course understandable, that we can’t touch these objects of desire), since we have the satisfaction of engaging with everything that surrounds some very important work. For those with a fondness for the neo-avant-garde scene of the ’60′s and 70′s, the show is not to be missed, simply because it offers such an intimate and unpolished experience of that moment. As a collection of fascinating objects, Sculpture in So Many Words is beyond reproach; its challenge is in convincing us that all these text pieces actually work, independently, as text pieces or that, deprived of their referents, they do in fact represent Mr. Hart’s “language lab” of contemporary sculptural practice.