-

Preservation and the Composite

by A.E. Zimmer June 12, 2012

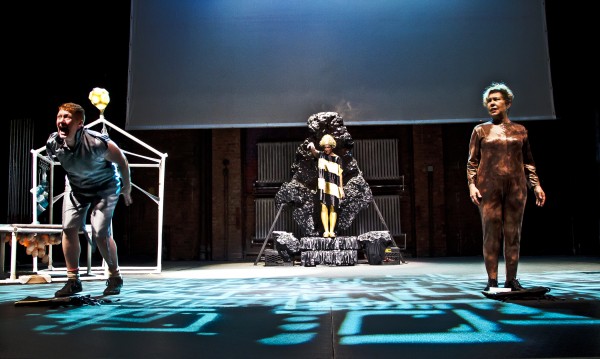

image by Ves Pitts. courtesy of El Museo Del Barrio & Performance Space 122.

Up on 104th street, El Museo Del Barrio’s theater is dim. Its stage is gaunt with white backdrop, lit by glowing props that seem the outcropping of some strange mind’s vision of dystopia. At one end sits a great gyroscopic orb, looking as if it could measure some quality of the future currently immeasurable. Stage left, a primordial cot stretches toward the audience, a net of glowing orbs strewn beneath it’s underside, casting the theater into a wan, curious relief. The more the contraptions are inspected, the more there nature grow exceedingly ambiguous — with one squint they seem entirely foreign, and then suddenly, the familiar sheen of PVC pipe peeks through, recognizable, and any New Yorker’s carping investigation is soon squelched. Ah, these things are made out of trash, the audience realizes. All of this is recycled.

These are the introductory symbols of Post-Plastica, the newest work by Ela Troyano and sister Alina — who is perhaps best known as Carmelita Tropicana, the outrageous, Loisaida-hailing, termagant vixen. Since her debut in the New York art scene of the eighties, Tropicana’s use of camp, comedy, drag and raillery has made her a cultural helmswoman in the exploration of queer Latino and Cuban-American experience. Herself an entity of many shades and fractals, Post-Plastica is similarly a radical puzzle piece of mediums and media — part video installation, part theater play, part performance.

As amalgamated as its parts seem, Post-Plastica is a fable in the strictest sense. It begins with a video introduction of Plastica, or Maggie — a Poughkeepsie-bred, recent art-school graduate turned usurper, played by Erin Markey. After an internship turns to friendship, Maggie parleys the Hispanic artists’ ideas and ambitions into a sudden and tremendous celebrity art career, complete with new and exotic moniker. Enraged with the news of Plastica’s success, a downtrodden Tropicana departs on a fatalistic downward spiral. Hunched over laptop, she imbibes a ludicrous combination of Diet Coke and Mentos before spearing herself with a syringe full of “bad Botox”. The binge sends her into coma, and Tropicana’s image cuts out, replaced with found footage of our present-day techno-revolutions: masses of people huddled together, phones outstretched to record their own happening. “The revolutions are everywhere,” Carmelita ruminates, now disembodied. “The revolutions are Diet Coke”.

Then the screen lifts. Our performer stands to welcoming applause, a massive altar behind her. Arms outstretched, face tilted toward the heavens, she is half- Virgin de Guadalupe, half- Rip Van Winkle. Her body has been sustained well into the future in its comatose state, thanks to the care of HB25, or Ursaan admiring scientist, played by a cool Becca Blackwell. As Tropicana’s character awakens to the future, she immediately chugs out her name in an unpracticed voice: “H-O, Ho.” In their first interactions, Ursa explains that Ho is a relic of the past, infamous in this dystopian future as The Ancient. Like a fossil, her body has been maintained and cultivated to extract information of time gone by, “when animals still existed, when nature had not yet been improved upon”. Ursa’s every move is by direct order of the CEO, the omnipotent ruler of the future. Also played by Markey, the CEO tells of the conditions of her empire, a world literally built on the detritus of our time, “mountains of plastic that have withstood disaster.”

What ensues is a fantastic and laudable journey through worlds old and new. As the CEO grooms her debut to the public as precious artifact, Ho is forced to re-constitute in this dystopia, moving through a kind of infancy. And, true to Carmelita’s form, each milestone is not without a solid ribbing of the socio-cultural normatives that be. As her body thaws enough to become animate, Ho is urged to wear the garb of the future. “Here, put this on,” Ursa encourages, holding up a spangled, bulbous dress. “It’s what all the girls wear these days.” Ho’s language, too, is garbled until again she retains fluency. “I thought she would be speaking in complete sentences by now” the CEO sighs, as Ho spurts outbursts of “gibberish”, a pointed mélange of English, then Spanish, before Ho squeezes out information with stunted consistency. “ I know I sound like soundbite,” she says, explaining this as the favored communication of her time.

It’s no coincidence that this farcical play on language is a conflagration of Troyano’s cultural memory as much as it is comedic stratagem. Carmelita Tropicana the character, was birthed in parts: an aggregate of Troyano’s many “lives” as lesbian, Cubana, performer and artist. Post-Plastica, too, is such a composite; its setting a literal re-structuring of the waste Ho’s world left behind in its ending. As such, this “recycled” world functions with absurd, discordant life– it’s CEO is a fragmented hologram constantly disposed of her body (and at times, her grip on power). Ursa, too, is hybridist: in a comedic love scene between she and Ho, she’s found out to have a tail, forced to explain herself as a twisted half-woman, half-polar bear.

Certainly, Post-Plastica’s aforementioned suppositions and realities don’t rely on a linearity of any kind, nor terribly determined plot or thru-line. This is perhaps to be expected from Troyano if her past work–dizzying in multicultural (“mucho multi”) reference and layering– is to indicate. However, what is masterful about ancient’s interplay is the way Troyano manages to subvert the very legacy that’s made her. In Ho, “the ancient”, lies age and substance organic. It is not the muddling of her background which makes her relevant but the wholeness of her flesh and blood — queerness, nor race or dialect, specify her. Instead, it is her very humanness that is “ancient”, and thus rareified. Her value in this world is confirmed in her existence as fragile mortal. Ho, silly name and all, is miraculous proof of life, non-recyclable–even after the Botox-botched attempt to adorn herself otherwise.

By the piece’s end, Ho and Ursa attempt to rally against the villanous CEO but are thwarted. The stage fades to another video projection. The audience is thrown back into the past, inundated with a collage of warm moments between Plastica and Ho. The video ends with a lingering image of Plastica, teary-eyed and reflective, perhaps even remorseful. She holds a rose tenderly in her hand. Then, belying any too-prolonged sentiment, comically shoves the petals in her mouth.

The lights come on, and the future and its CEO are replaced with Plastica. She stands on stage, moving through a lengthy monologue, thanking both museum and audience for attending what is now suddenly her newest exhibition. In a mind-bending twist, she descends the stage, motioning all to come out to the lobby to view her newest work. The crowd empties the theater to find Ursa and Ho, two parts to Plastica’s newest “triptych”. Ursa stands on marble pedestal with headphones, moving to an unheard beat. Ho flanks her left side in what’s clearly a Hirstian aquarium-cum-moratorium, ostensibly pickled for “art’s sake”. It’s a hysterically grim ending, but as voyeurism and exhibitionism collide in this performance, one recalls that initial phrase: “The revolutions are Diet Coke”. One can’t help but feel Troyano’s Post-Plastica is ultimately a critique of culture’s affinity for preservation — both its merits and follies. Perhaps the revolutions are Diet Coke because the revolutions are mutant, their attempt to preserve, record and make insoluble their presence a kind of dysmorphic failure. Perhaps the revolutions are alight with electric idea, but are eclipsed by their own static, their inability to mold and change into something fundamental, lasting, ancient.