-

We Survive Among Elements of Our Own Demise: Ben Rivers on Two Years at Sea

by Aaron Cutler May 20, 2012

We the People, declared the title of Ben Rivers’ 2004 short film, predicting the subjects of movies to come. Black-and-white views of an empty, narrow street between buildings; mob cries alternating with the noise of one lone pair of shoes. Who are they? Where are they? When is this?

These questions come up in Rivers’s films, which leave you uncertain, but curious and grasping to know more. The people and habitats can fit together sweetly; in A World Rattled of Habit (2008), a Russian émigré and his adult son lounge around their sloppy trailer, listening to music. The jolly, fat elder recalls his family’s problems and his travels from Russia to the States to Germany to England. “So all mission of each individual, my way, you have to see that through, and navigate through the shit it’s you’re floating through,” he says of life.

The joy of Rivers’s movies is often mixed with dread. May Tomorrow Shine the Brightest of All Your Many Days As It Will Be Your Last (2009, co-directed with Paul Harnden) shakily shows cloaked figures moving through woods, followed by soldiers, and seeking quiet places to read, seemingly in escape from some kind of disaster. A metallic ring obscures words spoken offscreen; wind blows through shimmering trees. It’s only occasionally that we see faces beneath their cloaks—a solemn old man, a blankly gazing old woman.

The 39 year-old Rivers originally studied sculpture at the Falmouth School of Art in his native England, then made installations, then moved to 16mm cinema in search of better ways to capture the human form. Lately he’s been watching how people move through landscapes. The old hands work slowly and gracefully, heads down, through the aging factory in Sack Barrow (2011); the children play freely in the trash heap, turning to show off the odd monster masks they’ve made in Ah, Liberty! (2008); Jake Williams tromps through the woods, his boots crunching snow, in Rivers’s first feature, Two Years at Sea (2011).

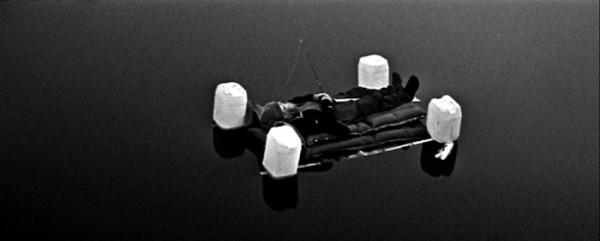

The slim, balding, long-bearded Williams worked for two years in the Far East as a merchant seaman, saving up enough money to make a place for himself back in England, but far from its madding crowd. Sea is his third film with Rivers and, like the other two (This is My Land [2006] and I Know Where I’m Going [2009]), it’s set around his country home. He walks through the large wooden house and showers in a trailer, his cat keeping him company. He explores the surrounding hills, sometimes silently, sometimes accompanied by Indian records. He eventually heads to the lake, makes himself a boat, and sets out on the water before returning to land. It’s that simple, perhaps.

Yet there’s something disquieting about this Paradise, perhaps the feeling that it could be lost. The large ‘Scope framing full of objects suggests Jake’s a small, temporary piece of this place, which can keep living without him; the continual changing of the seasons affirms it will.

Sea addresses one of Rivers’s lingering concerns, which is the fragility of any man-made paradise—always temporary, maybe, because life is short. The photos of unidentified smiling people that appear periodically, frozen, recall the still images that open the filmmaker’s earlier Slow Action (2010) (showing in New York this Sunday, May 20, as part of this year’s Migrating Forms festival). Slow Action is a catalogue of imaginary Utopias, combining images of depopulated islands with “Memories not of what has been, but of what might be,” as put by one of two narrators speaking sci-fi writer Mark von Schlegell’s stunning voiceover. We learn that, “Everywhere new utopias are possible,” but also that, “Utopia is by definition no place: It can only be approached, never reached.” The questions of whether Jake lives in a utopia, and how long it can last if he does, haunt Two Years, especially since the movie leaves them open.

Ideal worlds are built from elements of the real thing. Rivers’s movies take known worlds and then estrange them, encouraging us to create our own spaces beyond the frame. His people are always moving towards something, though that something is rarely specified. Whether their initial settings are familiarly working-class or exotically tropical, there’s always the feeling that they can go somewhere else, somewhere undiscovered. I think that’s what ultimately accounts for the conflicting sensations the films give of exhilaration and quiet terror. The prospect of pure freedom is unnerving, partly because it means giving up what we know. As Jake sets out on the water in Two Years at Sea, his raft lit by candles, one can recall Slow Action’s “principle of possible abandonment necessary to any utopia… At any time, one may leave the island on a boat.”

I spoke to Rivers at this year’s Rotterdam festival about Sea in particular, a few months before it would screen near my home in São Paulo. A new film, Phantoms of a Libertine, recently premiered at London’s Kate MacGarry gallery, and later this year will come A Spell to Ward Off the Darkness, made in collaboration with the American Ben Russell. Yet each of Rivers’s movies gives the sense of being part of a continuing evolution, and you feel that any time you talk about one, you’re also discussing the rest. This includes all the films we only imagine.

You’ve said you’re a big Paul Sharits fan.

I wouldn’t single him out as the experimental filmmaker that had the biggest impact on me. It’s an accumulative thing. From art school I started running a film club, then I moved to Brighton, and then some friends and I opened a cinema. We were screening three times a week, and we would show a lot of experimental work. Sharits was one of those people that we showed quite a lot, but that was probably more my co-programmer’s choice than mine. I showed a lot of George Kuchar. I’m a huge George Kuchar fan. I’d say, of all the experimentalists, he probably had the biggest impact. For starters, he was the first I saw.

I’d only ever seen feature films before, so I had no idea that there was this enormous other world of cinema. When I was at art school someone gave me a videotape with four Kuchar films on it which the BFI had released, and it just had this profound effect of showing me a whole different set of possibilities. Seeing things like Sharits is like seeing film as even a physical moment, which is something you can get with some action films, but it’s very different because it’s not—it’s purely about that kind of assault. It doesn’t try to pull you in any other way, in any deceptive way with narrative and manipulation. It’s there, and you’re there with it. That was pretty impressive. With George Kuchar I was struck by his beautiful cinematography, amazing editing and sound, the use of found music, all made with extremely independent means. As someone at art school, with no film teaching, it was enough to see that making films was possible if I just got a Super-8 camera, filmed my friends, edited on an 8mm viewer, and then played the films with accompanying soundtracks stolen mainly from old Universal Pictures films. If I hadn’t seen Kuchar I may have made the mistake of going to film school.

Then there were other people that I discovered along the way, like Ron Rice, Margaret Tait, John Smith, Bruce Baillie, Chick Strand, I could go on for ages… but watching experimental films always went alongside watching all other kinds of filmmaking, and this was the ethos of Brighton Cinematheque, that we would show all different forms of cinema; it’s all cinema.

Sharits is very formal and structural, while Kuchar is much more prone to following human beings. With Two Years at Sea, you’re using a person as a formal element.

He’s also very human. He’s someone I’m very attached to, and whom I feel a lot of warmth towards. When you talk about him as a formal element that makes him sound too much like he’s a Bressonian model or something, which I probably wouldn’t go along with.

I mean more like what Brakhage said—“All that is is light.” When you were filming, how conscious were you of him as an actual person with needs and desires, and how conscious were you of him as a visual subject?

I think it’s a simultaneous thing. I try and stay aware of them both. When you’re looking through the viewfinder, then it can become more formal. I have a fairly clear idea when I compose the kind of images that I want, so that does usually mean that it can be like moving a human being to fit your requirements – but it’s looser than the usual blocking out of a scene – I think I will often make a person aware of the parameters of the shot and they can move freely within that. Sometimes this isn’t possible, because the shot parameters are too tight, so it does need blocking. The thing is, I watch his movements and I am following them before I run the camera. Then the ways I move him are basically ways that he would ordinarily move. As a filmmaker, for the sake of the film, you need a certain control; otherwise you’re not going to be satisfied with the film that you are making. I guess it’s trying to find a balance between the human being and the form, and not being too megalomaniacal.

The way that I compose images is pretty instinctive, though that word can be misleading, because it suggests not being aware of what you are doing – but actually I take quite a while to consider shots, it’s just that I only like to do it when I’m looking through the lens. I don’t use storyboards. I don’t pre-plan shots that much. I basically work from lists. It would be “Shower,” “Eating,” “Toilet,” often just single words—a list of single words. Then I’d compose the image with the camera. It’s about finding and feeling what’s right in that moment between Jake, myself, and the camera.

This is the third film you’ve made with Jake. How was the experience different from on the first two?

When I first visited Jake in 2005, on the recommendation of my friend Paul Harnden, who used to live nearby, I had never filmed someone in anything like an observational way before—if people had been in my films they had been directed entirely. Jake was completely welcoming, and after a couple days he seemed very easy with me filming whatever I wanted, some people are just naturals. I shot the first half of the film, not knowing is was the first half until I edited it, then went back in winter to film the second half. Jake enjoyed This Is My Land – so a few years later, when I was driving through blizzards on my way to the Isle of Mull making I Know Where I’m Going, I decided to call in on Jake – and once again he was completely at ease in front of the camera, allowing me film him going about his business. The big difference when I decided to go back again for Two Years At Sea was that I didn’t want him to lead and for the camera to follow, as that would have seemed like repeating what we had done before—so this time I directed, but he retains the same ease in front of the camera, which makes people believe they are watching a straightforward documentary—and this is testament to what a good performer Jake is.

To what extent did you let Jake guide the movie?

I talk about it as collaboration, because we discussed everything. He wouldn’t do anything that he was uncomfortable with doing. There are things in the film that he wouldn’t ordinarily do, with which he was a little bit reluctant, but not so reluctant that he would say no. But there’s also a lot in the film that he governs just by the very nature of being who he is. I can’t think of a better word than “collaboration,” because we sit and have long chats together in the evening. We talk about what the film might be, but this is interspersed between conversations about anything. Stuff going in his life, stuff going on in the world, whatever—just conversation. We don’t even talk about the film that much; it’s like, “OK, I want to do the scene on a lake. How are we gonna do that? Are you OK with doing that?” It’s more like practicalities.

I feel like what’s in the film is mainly, in the end, my decision, and he’s quite happy to go along with all that. It’s not an observational film in that I’m observing him with the camera. It’s observational in that I spend a lot of time observing his life and then I build scenes and shots around what I’ve seen. So it’s more like a reenactment of his life with elements of fiction. This is how I work with all the people in my films – in the end it has nothing to do with making a representational film about the facts of someone’s life, but working with them, using parts of their life and world to make a new one for cinema.

Is that how you think of the film, as being between fiction and documentary?

Yes, because that’s really one of the first things I spoke to him about, which was that I didn’t want to make a documentary. I’m interested in cinema, and I don’t believe in that idea of the objective image. Films are by their nature constructions. Since you choose to point the camera a certain way, you’re in a sense fictionalizing the space. So in making the film the way I did, him reenacting parts of his life also enabled me to move beyond that and into more fictional spaces where he’s playing someone similar to who he is. It’s an exaggeration of certain parts of his life. It leaves out a great deal of the reality of his life. It’s about creating a world that exists just within the film. That’s always my intention, for the film to become a hermetic world.

In a way that’s the theme of the film itself.

Yes, exactly.

Did you always know it would be a sound film?

Yes, I did. But I didn’t always know whether there was going to be dialogue. In the very beginning I thought that there would be other people, so that there would be conversation. And then, after that, I decided that I wanted it to just be Jake, but I still thought that maybe there might be some internal dialogue or monologues or something like that, even him talking to the camera. But I quickly decided that was not the way to move forward. It felt like a nice challenge to set for myself: to make a film with one person, no speech. It did feel like a challenge to try and make that in a way that wasn’t boring, because people like to hear voices. It’s a way of connecting to another human being. But I really like his face, I think he’s got a great face, and he’s very charismatic, he’s very photogenic, and that’s half the battle, in a way. I felt like he could carry the film in his face.

I’m glad you didn’t ask him to shave.

Oh God, I think he’s probably had a beard since the ‘70s.

Aside from the articulated words in the songs, do you feel that there is language in the film? If so, what, and what kinds?

He does say a couple of things. There’s also a language of gestures, and the language of images. I would say that his movements and gestures are a language of sorts. There’s also a language of the objects you see in the film, of space and of the way that space is constructed, the things that he has accumulated. You could look at them as a kind of language we’ve built up to picture the person he is. The things that one surrounds oneself with. The language of cinema.

Even though there aren’t other people in the movie, I do see him interacting with other characters—the lake, the objects in his house, the boat he goes out on.

His cat is a pretty crucial bit of company; that cat’s been there for a long time. It’s really about his relationship with that landscape and with those things around him. You don’t necessarily need other people to have different characters. Which was why I decided in the end just to have him. I thought it was enough just to have him interacting with all this other stuff around him. As much as he likes other people, the overriding desire above being around other people was being in that place. That was the strongest draw. So it seemed like the most important thing to try and get over was that relationship.

How did you find the film’s structure?

Months of fiddling. Editing takes me a while. Playing around with sound is quite often why, adding sounds to images to give them life and take them in different directions. I knew I wanted photographs to figure in the film, and for quite a while they occurred all at the same moment, with Jake looking through them. That was how it was edited for a while. And then I realized that I could use them as a kind of chapter headings. Because the way that it was coming together felt episodic. The lake scene. The caravan scene. It just made sense to have them as episodes with these chapter breaks. The beginning and the end were pretty clear in my mind early on, with him walking through the snow, returning home, and the fire fading to blackness.

Do you think Jake lives in a Utopia?

One of the reasons I’m interested in Utopia is that what it means to one person can be the opposite of what it means to another—this is partly what Slow Action is all about. Jake’s place in Two Years at Sea is close to a kind of utopia, as it’s the dream he had of living, achieved. The thing is, it is imperfect, and it is in these imperfections and contradictions that my interests lie—I am not really excited by the idea of finding the perfect place, and the word utopia points to this: it is no place, unattainable, but we can try at least to get near it. Jake’s world is very close to what he had wanted, but there is also underlying unease—this could be related to loneliness, or to the broken and discarded memories of society strewn around, or to the felled trees that he sees when he goes for walks that look like part of the devastated landscape they are in, or the weather, perhaps. So there is a great deal of joy and freedom to be had, but there are complications in that, and I like that.

You processed the film in your kitchen sink. Why?

It was partly tied into the decision to film in black and white – I was having difficulty deciding whether to film in color or not, and in the end thought that black and white would help move the film away from an idea of documentary if paired with the ‘Scope ratio. I also decided to use black and white because it would help mask some discontinuity, of which I thought there might be a lot, because I knew I would be filming on and off over the course of a year. The final push was that Kodak announced they would stop producing plus-x film, so I bought as much as I could find and filled my fridge.

This leads back to the hand-processing, which feels appropriate to my filmmaking and particularly to this film. I’ve made a series of films about people who live off in the wilderness, and they live very physical lives, and you’re there with the dirt and the muck and the elements and all that stuff, and it’s not in any way sanitized. I think that to mirror that with the physical nature of film—having my hands on it, processing it, not handing it over to a kind of mechanized or industrialized way of working—was important. It’s hands-on, do-it-yourself. It makes sense as a continuation of what I’m interested in, in Jake’s life and in some of the other people’s lives. It feels natural.

For Amos Vogel, with thanks to Andréa Picard for research help.