-

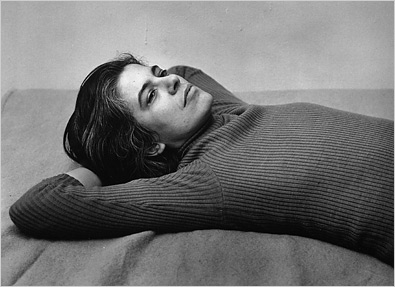

In the Margins of Life

by Debora Kuan May 15, 2012

As Consciousness is Harnessed to Flesh: Journals and Notebooks 1964-1980

Susan Sontag, ed. by David Rieff. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012.As Consciousness is Harnessed to Flesh: Journals and Notebooks 1964-1980 is the second volume in the three-part series that comprises Susan Sontag’s journals and notebooks, and follows Reborn, published in 2008 to apprehensive reviews. David Rieff, who edited the series, writes in the foreword that if Reborn can be seen as his mother’s bildungsroman, the equivalent of her youthful literary hero Thomas Mann’s Buddenbooks, then As Consciousness might in turn be seen as “the novel of vigorous, successful adulthood.” The book, of course, is not a novel, but a notebook — a collection of ideas and diaristic episodes, possibly written with the future goal of an autobiography or large autobiographical novel in mind. As a result, this second volume, saddled with a rather cumbersome title (one of Sontag’s notes in the margins of 1965) and weighing in at a hefty 500+ pages, is unlikely to be read cover to cover with much enthusiasm by anyone not already a Sontag aficionado. The book is notational and elliptical at best, brimming with vague pronouncements (“The only acceptable life is a failure”); unanswered questions (“The autobiography of a guru? How do I feel about sublimation?”); fragmentary ideas; borrowed quotations; to-read and have-read lists; and enigmatic, often poetic, monads (“A spy in the house of life”).

That said, As Consciousness does manage to reveal an adult Sontag very much consistent with the budding adolescent intellectual we met in Reborn — self-critical, categorical in her tastes and opinions, deeply anguished, and always, always at work. The very nature of these journal entries attests to the constancy of her mind and her efforts, although she is self-aware enough to realize that the psychological underpinnings of this ambition may be undesirable. “I valued,” she writes, “professional competence + force, think (since age four?) that that was, at least, more attainable than being lovable ‘just as a person.’” The quotes around “just as a person,” not to mention the “just,” are telling, implying not only an unfamiliarity with, or suspicion of, the concept of being loved merely for who one is, but perhaps also a twinge of disdain for the notion of not being proficient enough in a particular métier to be loved for a reason.

Perhaps at the urging of her therapist Diana Kemeny, Sontag spends a good deal of this notebook examining the roots of such feelings in her childhood, finding her mother — an alcoholic who, she believed, equated her daughter’s happiness with disloyalty — in part to blame. Later, Sontag writes that the familial roles in her childhood were perversely inverted, as often happens in the homes of alcoholics.

This inherited dysfunction, not surprisingly, manifests itself in Sontag’s later relationships as feelings of subjugation, as well as sexual inadequacy. At the opening of the book, her tumultuous relationship with the Cuban playwright Maria Irene Fornes, whom she calls “I” or Irene, appears to be ending. Sontag is devastated — penning strange, flatline statements such as “There are people in the world” and alluding to Irene’s icy stonewalling: “There is no responsiveness, no forgiveness in her…Even a grunt of assent ‘violates’ her.’” And what seems even harsher about this rejection is that Sontag blames at least some of it on her deficiencies as a lover. “Self-respect,” she writes (her italics), “It would make me lovable. And it’s the secret of good sex.”

By 1970, however, she seems to regain some happiness and stability or “mastery,” as she calls it, with C (Carlotta), calling her “the first big intellectual event (this past week) since my trip to Hanoi.” Despite this self-professed mastery, however, Sontag’s vulnerability in love is still in full force. Indeed, gone in these entries is any trace of the self-assured critic; in her stead is a desperately insecure schoolgirl, chastening herself before a mirror: “I must be strong, permissive, unreproachful, capable of joy (independently of her), able to take care of my own needs (but playing down my ability, or wish, to take care of hers).” So much calculation and performance! And yet these feelings of insufficiency do not seem to cloud her joy. Instead she writes that at last she is no longer “busy dying” but “busy being born” — a bright, if not fraught, echo of her exhilarated teenage discovery of lesbianism in the first volume of notebooks, in which she famously declared she was reborn and then inexplicably married Philip Rieff.

For someone so desperately seeking love, however, Sontag could sometimes be a rather cold, withholding mother. She admits that she refused to breastfeed David as a baby in order to vindicate her own mother, who did not breastfeed her. When David as a young boy despairs that he is not as precocious as his mother was when she was his age, Sontag does not answer as one would expect her to — assuaging a child’s insecurity with a white lie — but instead simply lets him sit with the unhappy comparison.While the bulk of As Consciousness, like Reborn, turns inward in self-examination, Sontag does give us glimpses of the larger world, particularly in May of 1968, when she is invited, as part of a delegation of American antiwar activists, to North Vietnam by the North Vietnamese government. Here, as we rarely do in the book, we get to see through her eyes rather than into them:

A bare room, a low table, chairs. We all shake hands, then sit down. On the table: two plates of half-rotten green bananas, cigarettes, soggy cookies, a dish of paper-wrapped candies from China, tea-cups.

…

The first few days I am constantly comparing the Vietnamese with the Cuban revolution….And almost all my comparisons are favorable to the Cubans, unfavorable to the Vietnamese — by the standard of what is useful, instructive, imitable, relevant to American radicalism.Ultimately, though, it would not be this trip that changed Sontag’s attitude toward Communism. Instead, Rieff tells us in the foreword, it was Sontag’s close relationship to Joseph Brodsky that eventually motivated her to publicly recant her faith in Communism’s liberating potential, not just in its various iterations around the world, but wholly, as a system.

It is surely unfair to read a private diary in the hopes of liking its author. After all, we turn to our own diaries, if we keep them, more often when we are unhappy than happy. What, then, is the value of reading such private volumes, besides voyeurism? Perhaps the conscientious reader can derive some delight in linking up Sontag’s nascent ideas and notes with her essays (I, for one, found her admission of enjoying the sight of “deformed people” interesting considering her defense of Diane Arbus’s work as not sensational in On Photography); but even the casual reader can find some charm or bemusement in the fact that one of our greatest public intellectuals worried about her “fat legs” and kept lists of her likes (urinating, tall people) and dislikes (Robert Frost, German food), as a child would. Sontag uncensored, it turns out, can be as playful as she can be pitiable.

In the end, however, it may be what Sontag doesn’t write that reveals the most about her: most notably, her metastatic, stage-4 breast cancer — either her diagnosis in 1974, her radical mastectomy, or the harrowing regimen of chemotherapy and immunotherapy she underwent in the following years. For someone who has so much to say about everything, she has surprisingly little to say about this very grave matter. If she mentions it, it is brief or obscure, at times requiring David’s editorial hand to explain to the reader, This is a cancer reference. In 1976, she writes one image, “Surgeon’s green hospital shirt,” nothing else, and a few weeks later, she is immediately back to Beckett, Woolf, and the declaration that American poetry is weak — it contains no ideas. A few more pages in, she quotes an intern at Memorial Sloan-Kettering who calls cancer “a disease that doesn’t knock at your door first.” Not a particularly profound or illustrative statement, but that, oddly, is where Sontag begins and ends her thinking on the subject.

Compare this, say, to Joan Didion’s approach to her husband’s and child’s diseases in The Year of Magical Thinking, in which the very act of research, the wishful work of accumulating facts and statistics, helped to serve as a psychological buffer against death. Granted, she herself was not ill, but certainly she was terrified at the prospect of losing her dearest and nearest. Was Sontag in denial? Was she trying to distract herself from the physical suffering, the fear, with her work? Both seem likely, and reasonable, but the cryptically flat nature of her descriptions (“Changes in the body, changes in language, changes in the sense of time”) read oddly, revealing a bizarrely uneven equating of a life-threatening illness with her usual intellectual preoccupations, as if the former could not, without warning, simply wipe out everything. Perhaps this is how she survived, by dwelling on life as it was and insisting that life remain so. But such circumlocutions — for this reader at least — suggest that the true heart of these notebooks and of Sontag’s character lie not in what we see on the page, but rather, in what we can only limn in its white inviolate spaces.