-

A Painter’s Painter’s Paintings: Bill Jensen at Cheim and Read

by Brian Dupont February 27, 2012

One has only to look the length of recent exhibitions on Chelsea’s 25th street to understand: abstract painting that grows out of gesture, color, and an engagement with material pigment remains a touchstone of artistic practice, despite the waxing or waning fortunes of the medium1. The viscous stuff of paint will congeal into networks or scrawl, an écriture individual to each artist despite their common material. From the linear scratching of Dubuffet’s late paintings at Pace to Margaret Evangeline’s dry, ropy networks at Stux2, this mode of abstract painting engaged with an elemental consideration of line, and of late, commonly on view, forms a kind of informal family, drawing from various points along the form’s history. The toughest relation falls at the end of the block. After a few years and exhibitions in this crowded homestead, Bill Jensen has shown that he was just passing through.

Despite showing with well-respected blue chip galleries3, Jensen has remained restless and constantly searching within his painting practice, forgoing the comfort of signature subjects to focus on the process of making a painting. Where contemporaneous painters Brice Marden and Terry Winters4 emerged from the post-minimal era with a specific and identifiable interest in their respective thorough procedures (all founded on a deep respect for and understanding of the craft of painting), Jensen’s early work spoke a language built of forms excavated from the unconscious, and rife with totemic weight and symbolist reference. Scraping the canvas bare to start a singular investigation over (and over, and over) again, his references were the unfashionable Ryder and Hartley, Stout and Dove. This process, focused on finding a single path for each work has left him the respected Ethan to the adored Martin of his contemporaries. His work shuns any polish that would render them easier to live with, that would ingratiate him to wider public5. His work is easy to respect, but difficult to love.6

This respect is a result of Jensen spurning7 what the art world wants from painters. His surfaces have gone from thick, armor-like accumulations to raw, scraped traces highlighted with translucent color, but they are always unflattering and tough. His quest for a single image yields tendencies, not anything that could be described as a brand. Likewise he has not embraced the grand scale that signals high ambition (and high prices) within the art world. His works remain easel sized, and even at their largest, speak in a voice more intimate whisper than bombastic shout for attention. Quiet and unassuming, he is content to allow his pictures to stand for themselves, and as they always seem to be moving, the artist becomes hard to pin down.8

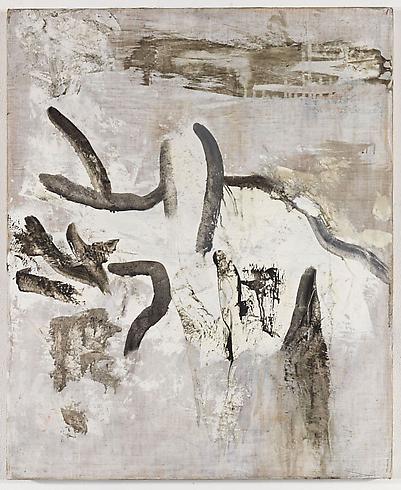

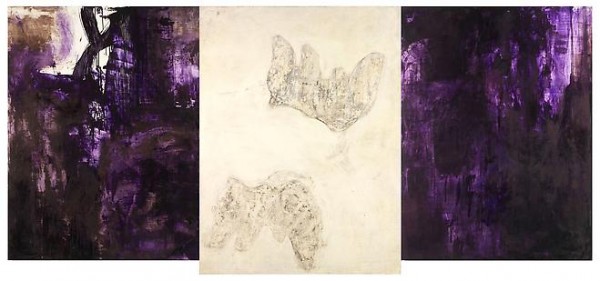

Jensen’s continual pilgrimage has been rendered in miniature in his current exhibition. Greeted by a triptych (The Trinity) upon opening the door, this show already promises new directions and ideas from the artist. The presentation is a dramatic introduction, centered through the archway and with dark, atmospheric purples of the central panel flanked on either side by forms seemingly unearthed from monochrome white. Entering the space (you are after all, invited) the other works in the front gallery show the first steps towards the triptych. The remaining works are all small, and predominately pale, with forms and spaces not quite coalescing into anything more solid than the paint they are made of. The paint itself is not an insubstantial matter: through it, the artist discovers new forms. They are not strictly sketches, but as small, autonomous works, they reveal the first steps of an artist working his way out of the bright colors and references to Asian calligraphy that dominated his last show, bridging an Chinese sense of space with a Northern European light and treatment of paint.9

The Main gallery turns to predominately dark works, and the confident statements of a painter who has found a new way. The triptychs take on references to the form’s use in medieval and renaissance altarpieces, combining familiar references to Chinese painting with the swirling atmosphere of Goya’s late black paintings. They offer a stark juxtaposition: thin and vaporous purples, umbers, and ochres contrast with plaster pale whites and off-whites that fill a ragged form, perhaps a rock formation or clenched hand, emerging or turning out of field with minimal gestural inflection. Where these scholar’s rocks are divided by the edge of a stretcher, the form continues and echoes, but does not retain any density. The picture continues, but the viewer must account for the shift between modes of abstraction. This shift between panels is a common trope within the format, from Bacon’s classic triptychs to Marden’s joined panels. Jensen’s success lies in a strikingly different manipulation of material that avoids disrupting the continuation of the image, while working neither figuratively nor with a lack of internal referent.10 The single paintings magnify the scale of the dark triptych panels by amplifying the impact of the gesture within a smaller physical space. While these singular pieces don’t make a bold challenge to historical form as the multi-panelled works do, they point to a greater range and synthesis of experiment, emotion, and mood within a single picture.

Stepping into the last gallery with a single painting on each wall is an exercise in playing catch-up, as Jensen has already set off on another search, looking for a new way. Black Sorrow (I) eases the transition, as distinct web-like traceries emerge from his scraping process, but the remaining three Book of Songs diptychs are an all together different animal. The forms are the same, but his paint is Tupernol thin and matte, and easily confused for smeared charcoal. The differently sized panels hang slightly apart, as rude forms reminiscent of Carroll Dunham are reduced to diagrams, mirroring each other from across the gap, their symmetries slightly contorting to match a unique perimeter. It is impossible to tell if the Black Sorrow (I) is a work in the same vein that was continued, or if Jensen saw the addition of a second panel as a divergent process yielding new results and thus deserving new consideration. These works are more reminiscent of drawings than finished paintings: where the mud and labor of dredging has always been important to his process, these works are notational and matter of fact. They return to line in a manner new to the artist, but are not open to interpretation or allusion. I suspect that it will be impossible to tell just which way Jensen will step next based on these works, if they are exercise, at an intermediate stage, a new beginning of false start.

Of Marden, Winters, and Jensen, all three have sought to find their way through a shared engagement with grids, traceries, and other manners of linear organization, though each artist is noted for working through different concerns. Winters moved inside his networks,11 focusing on the planes between vectors, applying his paint in a way less built than a matter of straight description.12 As Jerry Saltz noted, Marden has continued to refine himself out of his paintings, all the while producing handsome works. His bands and lines of color became more mechanical, yet carry a deeper charge of color, as if his early monochrome panels were stretched like taffy and looped around the canvas. His most recent show highlighted a sense of this return: flat, monochrome painted panels flank the edges of his web. Where Saltz asked if Marden might have another act left in him, it is ultimately a question that Jensen is beyond. Wherever his search takes him, Jensen’s practice is in constant motion. It is not a question of acts, but of steps along the journey.

Bill Jensen’s solo show ran at Cheim and Read, January 12 – February 18, 2012.

- Punctuated by the inevitable call of “is it dead yet? [↩]

- Punctuated by non-sequiters of actual bullet holes through steel panels. [↩]

- Showing with Mary Boone before he moved to Cheim and Read. [↩]

- who opened several shows across Matthew Marks spaces below 23rd street. [↩]

- And lead to mid-career retrospectives at major New York museums. [↩]

- Which is about the simplest definition of a “Painter’s painter” that I can think of. [↩]

- Obviously to a degree; one doesn’t wind up commanding a large ground floor space in Chelsea by being completely unmarketable. [↩]

- Branding is essentially the action of pinning a practice, person, or commodity down to a board, like any other butterfly. The collectors of the art world, like any other collector, certainly find pinned butterflies easier to manage than live ones. [↩]

- If one follows the order of works on the gallery website, the titles shift directly from Asian to European references, moving by way of Russia to the Netherlands. [↩]

- The brushstrokes themselves provide a minimal reference to space and scale, unlike a traditional monochrome (as in Marden). Frances Bacon has the canvas as window metaphor to fall back on, something he encouraged with elaborate framing. As this exhibition follows Joan Mitchell’s late works, herself a noted triptych-ist, there is a subtle difference in ambition. Mitchell would often simultaneously treat the seam as both continuation and starting point for a new mark, but the scale, pallet, and écriture remained unified. Jensen’s shift across the seam is much more dramatic. [↩]

- As he once appeared to move inside his seed-pods and flowers. [↩]

- In this sense his works have become more illustrative, his colors more decorative. Of the Variations being shown at Matthew Marks I find his notebooks and source material to be much more interesting than the paintings themselves, but I do not think the scale of these works as collage or drawing would satisfy his “brand.” [↩]