-

Archive Of A Changing City

by Monica Uszerowicz November 5, 2012

Much has been said about the hybrid role of Lower East Side legend Clayton Patterson: archivist, activist, artist. A former president of the Tattoo Society of New York — back when the act was illegal in New York State — the Alberta, Canada-born photographer, filmmaker, and painter has amassed over thirty years’ worth of video recordings and photographs documenting the Lower East Side of the 80s. Patterson photographed the neighborhood’s characters and ephemera almost obsessively, snapping gang members, cops, mystics, addicts, and anarchists in front of his apartment door. Eventually, Patterson’s practice took on a political slant: often working in tandem with his now-wife, Elsa Rensaa, the two filmed illegal evictions, the Tompkins Square Park Police Riot — the video of which landed Patterson in prison — and, eventually, the horrors of 9/11, effectively capturing on film what was arguably the end of an era.

The multiple layers contained in Patterson and Rensaa’s archives are rich, dense, too complex to enumerate, though they include the stories of characters like Lionel Ziprin, L.A. II — Keith Haring’s little-known collaborator — Bad Brains, street gang Satan Sinner Nomads, and drag queen Peter Kwaloff. They’re messy archives, too, neatly arranged but constantly growing and dissolving concurrently. A shot of the archives in a 2008 documentary about Patterson, Captured, is overwhelming: stacks upon stacks. Patterson has made a career of championing the underdog — he infamously quoted on Oprah that “Little Brother is watching Big Brother” — and documenting a substantial chunk of under appreciated but significant history. But: what to do with all of it?

With the help of willing volunteers and organizations — among them Steven Stories Press — Patterson has been turning his archives into books, the first of which was Captured: A Film and Video History of the Lower East Side. The latest,Jews: A People’s History of the Lower East Side, was recently funded by Kickstarter and is still in production. OHWOW published and distributed Front Door Book in 2009. I met with Patterson and Rensaa at their home — which doubles as the Clayton Patterson Gallery and Outlaw Art Museum — to discuss their history, the archives and their future.

Monica Uszerowicz: You’re an activist, but you’re also a visual artist. Can you tell me about your artistic background?

Clayton Patterson: I’ve always been an outsider artist. I started getting things going in Soho after I came to New York in 1979. I really didn’t like that yuppified world. It was heavy on gossip. What’s interesting is that Richard Brown Baker collected some of my stuff, and after he died, it was given to Yale. I’m now helping Jeremiah Newton with his collection of work by Candy Darling. Candy Darling, aside from being part of Warhol’s world, is also this kind of icon in the transgender world. There’s this collector, Laura Bailey, who is transgender, and she had this huge collection of gender and transgender material that got purchased by Yale, so we’re trying to get part of Candy Darling’s collection to Yale, taking into account that she, too, was transgender.

The thing about Yale is that it has three active archivists working on this transgender collection. That’s really important with archives. If you give an archive to a place and they don’t have money to deal with it, it can sit in boxes forever. But anyway: there’s a crossover if it goes to Yale, because it turns out Laura Bailey collected my book, Captured, because of some of the Lower East Side characters documented in it. That means it’s connected to Richard Brown Baker, and these links start getting made. Links are truly important.

MU: And your work is really all about links, in a way. Links between people.

CP: Exactly. Back to the art: I continued working outside of the mainstream, and then in 1985, I opened the Clayton Gallery and Outlaw Art Museum. I showed mostly outsider art. The ‘outlaw’ factor pertains not only to criminality, though that is included. My time as a so-called outlaw plays a role, too. The police considered a lot of my documentation a criminal law; I went to court for well over twenty years for documenting on the street, such as the Tompkins Square Park Police Riot video, which I made in August 1988 with the assistance of Elsa Rensaa. I was arrested after some of the portions of the tape were put on the news. This was the first time a hand-held, commercially available video camera was ever used in a case like this. Eventually several cops were fired.

It’s said that history is really created and made by the victors. And in a way, it’s true. Artists must document everything they do in order to stabilize it. The chance of you being recognized for your contribution can be lost. You need to clarify your own work. Even now, I might be considered a legend in certain arenas, but that’s not part of the larger arena. If you go to Harvard and ask who I am, nobody will know. But if you’re hanging out at Max Fish, someone will say, “Oh yeah, that guy’s a legend!” That doesn’t really translate in a historical way.

MU: Your archives hold a lot of stories. You’ve gained a very broad, encompassing understanding of that world.

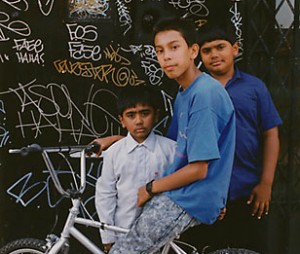

CP: That’s true, but I never focused on the upper echelon. My interest was always in the outsiders, the low end. The focus is inner city people. On the cover of the Front Door Book, which I published with OHWOW, there is a picture of a security guard. He is no longer alive. I know his son, and that’s really one of the only pictures of his father that exists. There are a lot of pictures like that in the archives — pictures of kids who were in gangs, too. But these images aren’t really important on a larger, social scale.

MU: But you still feel what you’ve documented is significant, right?

CP: Of course. I understand that the real genius comes from the roots and up. So many people accomplished things while riding on the backs of others. I always tell people, if you really want to be famous, you have to groom and develop one idea. Eventually, the idea will expand and other people will understand it and it will become palatable. RuPaul is a good example of this. I started shooting photos at the Pyramid Club because of my friend Peter Kwaloff, who is now known as Sun PK. The Pyramid Club really contributed to the 1980s East Village drag scene. That’s where Nelson Sullivan — the person who turned me onto the video camera — filmed RuPaul and Peter in their early days. Peter had a different drag character every week at the Pyramid Club shows, which made it very complicated for people to catch onto him. RuPaul, on the other hand, was just one, accessible character. Nelson let all these people stay at his place: Lahoma, Larry Tee, RuPaul. Nelson made the introductions, made it all possible. Nelson introduced me to the video camera, so I have to respect that. RuPaul doesn’t write about him in his book, but Nelson changed a lot of people’s lives.

And you know, so much genius came from cheap rent, from the ability of people to just move here and live capably. Those roots are now being cut off. New York is so gentrified that it has eliminated the gene pool. Genius is the fresh ideas, the outside ideas, the ones that change how we see and think. A lot of it came from the poor, the impoverished, the inner city.

MU: And so much of it is in the archives.

CP: One of the reasons I make these books, the anthologies, is that you need a hard copy of this. When you get on the Internet, you skim. You do searches. With a book like Captured, I included people who I felt were really critical to the whole situation, but were maybe unknown or obscure. Different people have different opinions about why something happened. You want to give everyone a voice. In the end, you’ll never know who was really right. In Resistance: A Radical and Social History of the Lower East Side, we featured an excerpt from a book by Ron Casanova, who was homeless and living in Tompkins Square Park during the police riot. He mentions that the police made a deal with the homeless population regarding a portion of the park in which they could legally stay. So the story about the police giving the park a curfew, thus closing it to everyone there, was an outrage. That’s what the riot was about.

MU: When you read history, it’s usually filtered through one voice, one idea. And that’s what the history becomes. Maybe you’re trying to prevent that.

CP: Right. I’m finishing up Jews: A People’s History of the Lower East Side, and I included a history of Lionel Ziprin, who was a major voice of his time period. He never became to famous — he wanted to remain obscure — but he will exist in the book. People who look in the book for Allen Ginsberg will eventually be led to Lionel. They’ll find Lionel and then a new door is open, new ideas flow. When you look back at art history, all those people you read about — Cézanne, van Gogh, DuChamp — the reality is that, yes, they were outside thinkers who were way ahead of their time, but many of them came from rich families. They were saved. Their work was saved. Other people who have made equal contributions, who were maybe influential to van Gogh — you’ll never know about them, because they will never exist.

MU: It’s overwhelming to think of all the incredibly creative people who were missed by history. But there are certainly famous artists who weren’t rich. Do you think luck plays a role in helping people become famous?

CP: I think a lot of it is attached to money and power and being within the system — or who you know. A lot of the ideas that percolate from the bottom take a long time to be understood. That’s why I say, if you develop an idea now, the masses have to understand it. But the masses aren’t the ones who change history. It’s the people who have a different understanding of things that change history — and that takes years to get to a wider public. That’s why it’s important to have those voices saved: if you don’t preserve it, it won’t exist. And that’s why I started doing these books. Hopefully, roots will grow out of this.

MU: When did you realize you were building this archives? When you first started documenting the neighborhood, did you know you wanted to specifically “store” these people, or was it just for artistic purposes at the time?

Elsa Rensaa: They asked Edmund Hillary why he climbed Mount Everest, and he said, “Because it’s there.” That’s what Clayton does. Because it’s there.

In a way. This is a very interesting question. It wasn’t really a plan or strategy. It developed naturally. I captured the last of the free and the wild and the crazy Lower East Side. It’ll never be that again. It was such a mix. And the great thing about immigrant populations, like you had in the Lower East Side, is that you get everyone from the idiot to the genius, because they’re all contained in that one package. A lot of it flourished — this great wealth of people that changed the history of New York.

MU: So you captured some of the last moments of the neighborhood containing a mix of different kinds of people.

CP: Now it’s homogenized. It’s about money, status. After the ’87 stock market crash, which didn’t affect real estate, rent kept going up. Now you have competition like NYU, which a corporation buying up billions of dollars worth of real estate. Then you have all of these real estate investments in companies. You have luxury hotels. These are solid bases that will forever change the structure and the economy of the neighborhood. America had a short period of time during which you could experience this Horatio Alger idea — pulling yourself up by the bootstraps. The possibility of coming up from the bottom and working your way up has been eliminated. Coming here from western Canada was like seeing the United Nations. Each culture that came from through the Lower East Side left something behind. You could experience a small part of their culture, and it was all very affordable.

MU: But how do you feel about places in the outer boroughs — neighborhoods that are ethnically diverse, cheaper than Manhattan, where a lot of artists are creating spaces for themselves?

CP: Well, the rent is cheap in those places for New York. But you still have to be working all the time to make that rent. And you don’t have that same cluster, that same density, of different kinds of people clinging together.

MU: Do you think that vibe can happen anywhere now, though?

CP: Well, I think the muse has left New York. People talk about New Orleans or Detroit as possibilities. I think China is a good example of a place where repression is happening, where it’s difficult, but the artists coming out of there — even the tattoo artists — are high-profile, really incredible. In the film, Captured, there’s a photograph of me leaving court during the trial for the Tompkins Square Park Police Riot tapes; it says “DUMP KOCH” on my hands. Ai Weiwei took that photograph.

Something else I documented was the transitional period the police experienced at that time. You didn’t just see artistic creativity there. In this instance, the creativity belonged to the cops. In the Riot tapes, one particular shot is interesting: the white shirt is waving for the blue shirts to stop, and they don’t listen. That meant the chain of command no longer existed. That’s what made it a police riot. In 1988, the police couldn’t control a ten-and-a-half-acre park in the Lower East Side. By 1992, the police were a razor-sharp, military organization that could control the streets anywhere.

Those cops spent four solid years down here re-organizing. This was the perfect petri dish for that. You had the anarchists, squatters, the drugs. They had lots of chances to practice down here, because they experienced real resistance from the locals. That resistance helped them to reorganize.

MU: Let me go back to the building of the archives. There is a struggle with it, regarding both its size and future purpose. Can you say more about this?

CP: Getting it recognized is hard. People are not really interested in this history. The people who were the geniuses, who bubbled up to the top, left the neighborhood and never looked back. By the time you get to their grandkids, who started coming back in the 1980s, or other people from that era — people like Blondie, John Zorn — they grow up and develop, too, and don’t necessarily think of themselves as part of the neighborhood’s history. They’re part of the history of punk, of rock. You kind of lose that connection to the roots of the neighborhood. And nobody has any real interest in the archives—nobody who could substantially do something with them.

MU: What are some other struggles?

CP: Economically, it’s a struggle. Trying to preserve the material is a struggle — a lot of it is dissolving and breaking down. Organizing everything is difficult, too. The lack of outside interest is hard. Making the books is hard. By the time the archives really get appreciated or loved or understood, a lot of it could be broken down. Also, Elsa and I are getting older, so it’s not something we’ll be able to manage or take care of.

MU: When you turn parts of the archives into books, they become utilitarian, educational tools. Why are the books important?

CP: It condenses the information and preserves the history. It creates layers. I think it’s one of the only ways to save the history down here, because it was so complex. History changes, memories change, and there’s no crust that holds the whole pie together. The books, hopefully, are that crust. Though I would like the book-making process to become easier. I have the ability to gather the information, but somebody in this world who can publish these books has to be interested. You want to be known and valued for what the archives really represent. So much of the roots of America came out of the Lower East Side.

ER: Years ago, Marshall Berman predicted what was going to happen with New York, and he was right in a lot of ways.

CP: There was always this big idea to turn the Lower East Side into what it wasn’t. You had Robert Moses, who wanted to put a big highway that cut through here into Williamsburg. Cooper Square caused that to be halted. Anyway, you don’t really have a radical community here anymore, no radical roots, so there’s no resistance to any of this.

MU: How do you feel about smaller-scale radical groups or artist communities in other neighborhoods, in New York or in other cities? I know the rent here is impossibly high, but do you feel that things like that are legitimate elsewhere?

CP: It’s not a matter of legitimacy. I think it’s a matter of passion and of connection. For example, I think a lot of people in Williamsburg aren’t really connected to the roots of the neighborhood the way people in the Lower East Side were.

MU: They’re not working with the people who’d been there.

CP: You can’t take a predominately black neighborhood and expect the new, white neighborhood to have any roots to it in the same kind of way. You don’t really have that base. There were people on the Lower East Side connected to the prior five generations. And for anything that artistic or radically significant to ever exist again, the model has to change. The model of the past was always connected to poverty and cheap rent.

MU: Yeah. It’s more expensive to do anything now, and I think people are more cynical. So — sum up for me what you’d like to see happen with these archives, besides the books. Do you want to see another Renaissance, or do you just want to make people understand the history?

CP: Of course I’d like to see another young generation develop and grow and flower out of this place, and to see people that didn’t come from wealth make a contribution to the world. My whole goal is to save the archives and put them in a place where they’re accessible to other people. I want people to be able to use them — to write, to learn. That’d be my ideal goal: something that isn’t static. I want this to be energized, to function, to be part of a community. I want it to be a wealth of material that other people can mine, get joy from, discover.