-

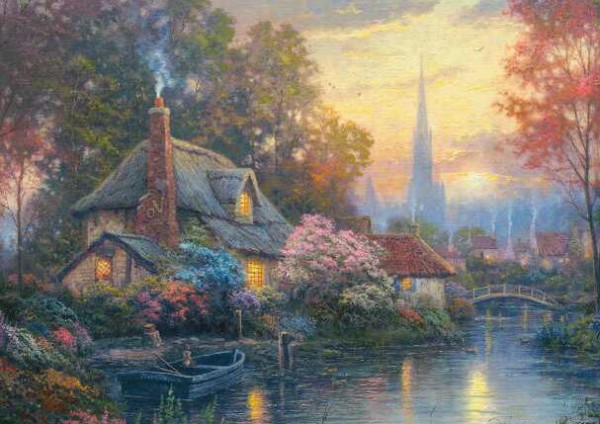

Cottage Pornography: The Charming Enigma of Thomas Kinkade

by Benjamin Evans April 17, 2012

Somewhere on the list of my top five art experiences is my first encounter with a “genuine” Thomas Kinkade. Like the first time I stood face to face with a Cezanne or a Basquiat (two other painters who have acquired a certain importance for me), the event had a surreal monumentality about it. For obscure reasons which I needn’t get into, one pre-Christmas not long ago I found myself wandering somewhat aimlessly in the Staten Island Mall. Unbeknownst to me, this was one of the select locations of an official Thomas Kinkade outlet. I immediately rushed in, enchanted and mesmerized. I knew the work, I knew his popularity among the general public, but somehow I had never been informed that the man owned his own retail outlets in malls across America. I must have been wearing a clean shirt, for the earnest sales clerk immediately identified me as something other than a regular looky-loo and approached me with a disarming smile as my head spun with the sheer vastness of Kinkade’s oeuvre. Calendars, prints, and posters, all displaying a bewildering variety of glowing cottages in all four seasons radiated in intense rainbow-pride color from every wall. Rendered defenseless by the opulence, the inconceivability of my surroundings, the besuited salesman easily led me to a kind of booth, a short hallway nook, all the while muttering what I took to be mystical incantations but were likely just bullet points from a brochure.

At the end of the nook was a painting, another cottage ready to explode with coziness beneath a gentle haze of woodsmoke. I heard something about a “recent innovation in painting technology”, and as the fellow manipulated a slider control on the wall, the lights in the booth dimmed, and before my very eyes the painting became darker and previously invisible stars began to glow in the sky. Against this descending wintry darkness no human soul could resist the impulse to make a dash for the cottage, to rush indoors and stroke a cat in front of a fireplace under a blanky with a mug of cocoa. An innovation in painting technology indeed!

I don’t know how I got out of the cottage and back into the mall. I just remember waking up at the food court having purchased a hot chocolate and checking to see if my wallet (and kidney) was still there.

Kinkade has always held an important place in my thinking about art, for several reasons. As has been noted in most of his obituaries, the “real art” world generally reviled Kinkade and his easy-cheesy sentimentality. As an artist, such easy dismissals are fine by me. Just as a fan of opera has no real obligation to consider the performances of a Britney Spears or a Shania Twain, neither does someone interested in, say, Rachel Whiteread or Neo Rausch have much obligation to pay attention to Kinkade (and of course, vice versa). As an artist, I have always thought that the dominance of this monolithic overarching concept of “art” is one of the most significant problems for artists today, and that we’d all benefit from following the example of the music-world with its obsessive but energizing categorization. But as a philosopher, or as someone who wants to think broadly about art and aesthetics, I do have an obligation to at least acknowledge the diversity of my field of interest. Thinkers about visual art have to face a phenomenon that includes not only canonical celebrities from Cezanne to Warhol, but also the Henry Dargers, Robert Batemens and Painters of Light.

Doing so, however, is difficult. Though debatable, let’s assume for now that all the recently lauded statistics are right, that Kinkade sold 100K worth of paintings per year, that 1 in 20 homes contains a work, and so on. Statistically he is the best selling painter ever to walk the planet. Jerry Saltz has (wisely) pointed out that sales figures are not a very interesting vector for evaluating an artist’s value1, but the point remains that his work (and its countless imitations) are extraordinarily popular, and demonstrate in an unequivocal manner just how undemocratic the structure of the “real” art world is. This observation itself may be something of a cliché by now, but I’m frequently staggered by how many young artists I meet feel that by practicing art they are associated not with an elitist, intellectual, aristocratic marketplace, but with a sort of grassroots populist movement, many of whom would agree wholeheartedly with Kinkade’s simple approach of art as an “inspirational tool.”

So the question is how to get Kinkade out of the picture, how to justify his dismissal. Saltz, in a very recent article2 that also acknowledges the “thought problem” generated by Kinkade, suggests quite simply that he is dismissed because of his total lack of originality:

Not one…of his ideas about subject-matter, surface, color, composition, touch, scale, form or skill is remotely original +

But I think we’ll have to do better than that. Surely Kinkade takes unoriginality to breathtakingly original heights? If cliché was fat, Kinkade’s cottage paintings would be the equivalent of deep fried bacon burgers floating in a warm butter soup. They’re just so unbelievably over the top, so pornographic in their banality — for my money they’re much closer to Koons Made in Heaven series than Norman Rockwell illustrations. They’re extensions of the great Komar and Melamid project that generated oil paintings based on surveys conducted by professional pollsters to determine the artistic preferences of different countries.3 Kinkade, without the aid of surveys, just tapped into an idea of what people like and proceeded to systematically generate dump-truck loads of it. Moreover, arguably this whole production was conceived of as a kind of deliberate critique. Fed up with the elitism of the art world in which he was trained, he responded with a very specific and intense rejection. A picture of a lovely little village at sunset is (paradoxically) a great fuck you to the theory-heavy debates of the 90’s art world, and the inevitable result of following a particular line of thinking to its logical conclusion.

One could also argue that Kinkade out-Warhols Warhol and beats Koons at his own game. With Warhol, for example, there were always overt statements, claims that it was all about money and fame, but these claims were frequently treated by apologists as cover for genuine occult or critical concerns. With Kinkade, his cover is so good we have no cause to suspect him of anything else (except, perhaps, during his occasional lapses into alcohol-induced escapades and pooh-bear urinations, which make him sound like just another Bushwick hipster on any given Sunday). It is not without some reason that Kinkade described himself as “the world’s most controversial artist.” For crying out loud — the guy designed entire subdivisions in which people actually live. By this standard, Koons has a long, long way to go.

Saltz writes:

The reason the art world doesn’t love Kinkade isn’t that it hates love, life, goodness or God. We may be silly or soulless or whatever, but we don’t automatically hate things with faith and love or that other people love. We’re not sociopaths. (Well, most of us aren’t) +

But the trouble is (as Saltz’s caveat hints), most of us sort of are sociopaths. If nothing else, Kinkade reminds us, or at least many of us, that we don’t like things that are popular, mostly because they are popular. We hold on to the notion, with increasingly stiff fingers, that art must be oppositional, confrontational to what is popular, and Kinkade makes this delightful bit of ideology (for that is what it is) clearly visible for us. This is not to say that there is anything wrong with being oppositional per se (surely there is a very great deal that is popular that does need opposing), but just to point out that rendering invisible ideology visible is itself a worthy project, and one that better respected artists have tried and failed to achieve. If we consider how previous avant-garde fuck yous have been reified and disarmed to become status symbols for the wealthy, we would do well to consider the challenge posed by Kinkade a little more deeply, even if it is partially a posthumous challenge presented by others.

A coda: Kinkade suggests that when people put his paintings on their walls, they are putting their values on the walls too. And that is likely true of me too: I put Siobhan McBride4 paintings on the wall, and that reflects my valuing of mystery, fatigue, ennui, discomfort, escape, release, life, and hope. Kinkade is a painter of light, McBride a painter of shadows. My preference is a reflection of deeper forces at work, forces of socialization as well as perhaps something deeper, at a more obscure part of my human being. Kinkade, in what is for me an experience of almost unforgivable badness, nevertheless reveals this deeply aesthetic core of myself almost as powerfully, if perhaps less pleasantly, than McBride’s more nuanced gouaches. Kinkade’s work reflects for me an “other” that I can never be but must only imagine: sitting inside the cottage, warm and toasty with a cup of tea in front of the fireplace, while I stand outside in the art world, in the mall, in my complex shadow, watching the glow-in-the-dark starlight emerge.

– April 15, 2012, Paris

- Jerry Saltz on ArtNet here, or originally on New York Magazine‘s Vulture blog here [↩]

- Ibid [↩]

- Likely the best place to review this project is through the DIA website and on their own site [↩]

- Siobhan McBride’s website [↩]