-

Tommy Hartung’s Anna: Constructing Dead Cinema

by Rachel Wetzler February 4, 2012

For his first solo show at the Orchard Street gallery On Stellar Rays, The Ascent of Man (2009), Tommy Hartung created a video inspired by scientist and historian Jacob Bronowski’s 1973 BBC documentary of the same name, which presented a vision of human history as a sweeping narrative of progress from proto-ape to modern civilization. In his second show at the gallery, Hartung once again took on a canonical narrative, albeit of a different kind: Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, often regarded as the greatest novel ever written, the crowning achievement of literary history, and one that is itself fundamentally concerned with notions of progress and social change.

The connection between Hartung’s film Anna and its ostensible subject, however, is hardly straightforward: The novel is less represented in the film than alluded to obliquely, its major themes and symbols torn out and reconstructed into a fragmented display of images. Indeed, the titular character of Anna is absent altogether, reflecting the fact that Hartung’s work is as much about the process of filmmaking as it is social and cultural history. The films are created in the artist’s studio using hand-crafted models and sets, stop-motion animation, low-fi special effects, and appropriated archival footage — in the case of Anna, the 1930 Soviet film Earth, part of director Alexander Dovzhenko’s “Ukraine Trilogy”. It is a process that draws attention to the ways in which a film is constructed, much as its disjointed imagery highlights the equally constructed nature of the large-scale narratives of history and progress that Hartung probes.

If the themes he addresses are often universal and triumphant, they appear, in his films, to be decomposing — literally broken apart through staccato cuts and disorienting effects. The film has no plot to speak of, at least not in any traditional sense; instead, its most appreciable message revolves around the collapse of narrative. The film presents a world in which ideology is shown to be suspect, linearity resisted. Hartung aptly refers to his work as “dead cinema,” pointing not only to the nature of the materials he employs — mannequins instead of human actors, handmade dioramas constructed in the studio that function as sets, archival footage borrowed from the medium’s past — but perhaps also to the much-discussed decline of “grand narratives” proclaimed by Lyotard to be the defining mark of postmodernism.

The ideas that Hartung’s films revolve around are ones that are outmoded, in decline, have failed, or no longer hold any currency. Earth, scenes from which are superimposed over Anna’s stop-motion tableaux, chronicles a fictional Ukrainian peasant insurrection against landowners resisting collectivization, the promise of a new social order in which a community of equals is at one with the land they work. From the vantage of the present, in which Stalinist collectivization policies signal totalitarianism rather than utopia, what was once an image of hope for the future comes to represent the failures of the past — we know how this story ends, after all. Both Anna Karenina and Earth are portrayals of society in the midst of upheaval, in which ideological battles and competing visions of progress come to the fore; as the exhibition’s press release notes, Hartung is concerned precisely with the “paradoxical failure of emancipatory ideologies to serve the needs of ordinary people,” and in his own film this failure seems to be embodied in a resistance to any semblance of a coherent narrative, a challenge to the notion of the forward march of progress.

Hartung’s films constantly call attention to their status as constructed images, refusing the viewer any illusion that they might be visions of reality: the mannequins and sets are crudely assembled, and, to an eye accustomed to the seamless effects of contemporary Hollywood cinema, Hartung’s techniques are plainly — and intentionally — obvious. As if to insist that we acknowledge Anna’s artifice, in the center of the gallery itself Hartung placed an installation composed of the mannequins and props used to create the film, accompanied by a camera track system, highlighting the process of making it by openly displaying the tools that facilitated its creation.

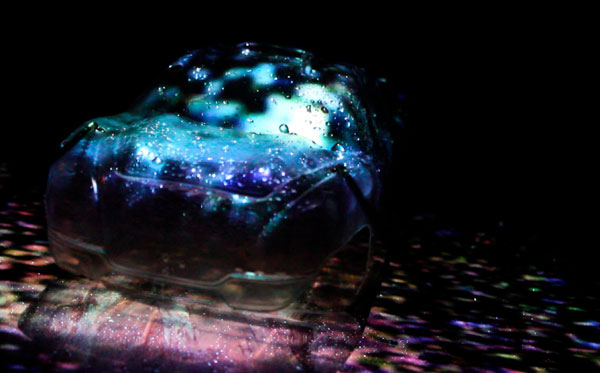

Within the gallery, sharing the viewer’s physical space, the mannequins have an unsettling presence: These are not the smooth, perfect plastic bodies of department store displays, but crudely rendered casts, daubed with paint and glitter. More importantly, they are dismembered and hollow, stuffed with candles, pipes, and wires, and surrounded by piles of salt and incense, creating a kind of perverse, uncanny shrine. Indeed, the image of the body-in-pieces carries its own loaded set of associations, both art historical and theoretical, immediately recalling Hans Bellmer’s Surrealist poupées, but also war imagery, with the mannequins’ metal appendages suggesting prosthetic limbs.

And yet foregrounding the means of constructing the film also serves to emphasize Hartung’s role as creator: As opposed to the large-scale operations of mainstream filmmaking, Hartung’s films are essentially one-man productions, in which the artist acts not only as director, but also set designer, cameraman, editor, and, indirectly, actor, as he brings the inanimate mannequins to life. That the films are created in his studio, often employing his own possessions — as part of his installation for MoMA PS1’s “Greater New York” in 2010, Hartung relocated his fish tank to the gallery, pet koi included — only serves to further confuse the boundary between process and product. A member of the gallery’s staff mentioned that Hartung would continue to shoot new footage throughout the run of the show, suggesting that the artist conceives of the project as an open-ended experiment rather than a finished work, itself a gesture of resistance against the notion that a narrative, whether cinematic or otherwise, must begin and end.

In this regard, the decision to show Anna on a flatscreen monitor at the back of the rather brightly-lit gallery, as opposed to a large-scale projection in a darkened room as the artist has done in the past, makes sense in theory, as it places equal emphasis on the film and the implements enabling its production, and allows the two to be viewed in tandem rather than privileging the final product. While this installation, which denies the viewer the immersive experience of cinema, might have been a conscious choice, intended to draw attention to the artifice of the medium, and, as the press release notes, “the problem of achieving credible representations of violence in today’s highly saturated visual culture,” it acts to the work’s detriment: What was undoubtedly both visually engaging and conceptually sound work felt slight in this context, with the small scale of the monitor diminishing the turbulent energy of the film. That Hartung’s art still manages to captivate in spite of less-than-ideal display conditions and poorly conceived exhibition design is a testament to its strength.

Tommy Hartung, Anna

On Stellar Rays, New York

October 30-December 23, 2011

Leave a Comment