-

Idle Thoughts: An Apology

by Jessica Loudis October 28, 2010

A new feature debuts today on Idiom, Idle Thoughts, wherein writers engage with older, canonized or forgotten works and ideas. Jessica Loudis, who will be leading the charge, such as it is, begins, appropriately enough, with Robert Louis Stevenson’s “An Apology for Idlers,” as she wanders her way through Penguin’s Great Ideas series. More to come, if we can get around to it.

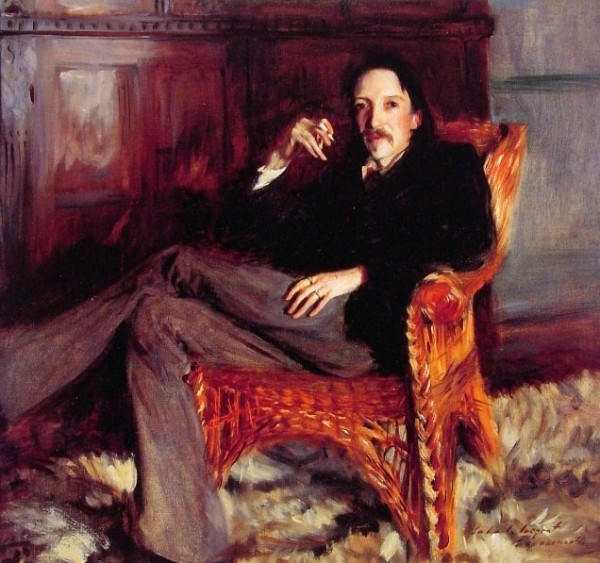

Seven years before Treasure Island was first serialized in a children’s magazine, Robert Louis Stevenson wrote “An Apology for Idlers,” a short essay on the virtues of sloth. He was 25 at the time—the ideal age to take up the charge—and had recently swapped a prospective future in engineering for one of books, bohemia, and his soon-to-be signature velveteen jacket. Most likely, he was feeling defensive about the decision.

Idleness is generally associated with 19th century dandies—Stevenson’s mustache alone earns him the distinction—and the French, but when “Idlers” was published in 1876, it intersected a longer tradition of literary lethargy. Japanese monk Yoshida Kenkō philosophized about the subject in his 14th century book, Essays in Idleness; Paul Lafargue wrote The Right to be Lazy from his prison cell in 1883, (he was, ironically, Karl Marx’s son-in-law); and fifty-six years after Stevenson, Bertrand Russell attacked the “immense harm… caused by the belief that work is virtuous,” in his own essay “In Praise of Idleness.” More recently, Cabinet Magazine has taken up the cause’s mantle, and assuming they ever go to print, several academic books are forthcoming on the subject.

Stevenson writes about idleness as it deserves to be written about—languorously, and with a hint of condescension. He characterizes the busy as a breed of latter-day zombies: glassy- eyed and driven, bereft of the imaginative capacity for dabbling, and thus resigned to a life of unacknowledged boredom. “As if a man’s soul were not too small to begin with, they have dwarfed and narrowed theirs by a life of work and no play; until here they are at forty, with a listless attention, a mind vacant of all material of amusement, and not one thought to rub against another, while they wait for the train.” It’s easy to mock Stevenson’s dismissiveness, but he’s quick to delineate between idleness—a form of inquisitive and generative aimlessness—and laziness, its apathetic doppelganger. The distinction is particularly relevant to the book’s desired audience: aspiring artists, or “young gentlemen,” as Stevenson would have it, eager to while away their time. In this regard, “Idlers” is less of an apology than it is a dispatch from the field.

Idleness is a slippery subject, as writing about it betrays its intent. There’s an out-of-time quality to Stevenson’s prose, a nostalgia for lazier moments that isn’t dissimilar to daydreaming or what I’d imagine light doses of morphine to feel like. After some musing about age, this intellectual meandering is called into relief in the final few essays—fond recollections of artists’ colonies outside Paris and seaside walks in the Bay of Monterrey—that feel vaguely as if they were written from a convalescent home. (Tellingly, Stevenson suffered from chronic illness for much of his life). Unlike travel writers who pack their writing with high-octane immediacy, Stevenson does the opposite, glazing everything over with a sepia-toned nostalgia, a wistfulness for things never to be recovered. This adds a slightly narcotic tint to his essays, but also makes it especially surprising when action does occur, like when the young artist sets fire to a California pine to see whether it will burn.

Reading “An Apology for Idlers” is to witness the process of aging over 113 pages. Idleness begins as a youthful pursuit, a form of undirected engagement; and ends as a mode of nostalgia, a trap door allowing the author to escape into literary solipsism. For those who can afford it, idling is a luxury as well as a curse. But as grim times make idleness more an imposition than a choice, “Apology” is an elegant reminder that sloth doesn’t always deserve its bad rep: It’s nice time, if you can use it.