-

Unguarded Affect: Leon Levinstein at the Met

by Jessica Loudis July 15, 2010

There’s always something dissonant about street photography in a museum. Polite observation and quiet reflection aren’t what these photos ask of their viewers, and when standing before a Robert Frank or Gary Winogrand, it’s difficult not to register a vague note of jealousy over the rift between well-behaved voyeurism and the glancing exuberance of the subjects. Or perhaps it’s just that on a nice summer day, I’d rather be outside. In any case, I’ll assume that the faulty air conditioning at the Met’s Hipsters, Hustlers, and Handball Players show was intended to address this concern, and to recreate the sweltering intimacy of photographer Leon Levinstein’s post-war New York.

Levinstein moved to New York in the late 1940s to study art and painting at the New School, and while he wasn’t partial to titles or dates, his photos from the ensuing decades carry many of the city’s signatures. During these years, Levinstein lurked on the streets and beaches of hardscrabble neighborhoods—the Lower East Side and Coney Island were favored targets—stealing shots before the show’s eponymous subjects could catch him. In the pre-paparazzi days of the 50s, conditions still worked in his favor. Photography was relatively rare, and many of his subjects, Levinstein noted in a 1988 interview, “didn’t know what the lens was.” This lack of affect suffuses every photo—his subjects sneer and pose in ways that should be impossible under the gaze of a camera. Seeing his world from the panoptic age of social networking, Levinstein’s work feels hyper-modern, and what’s more, utterly un-reproducible.

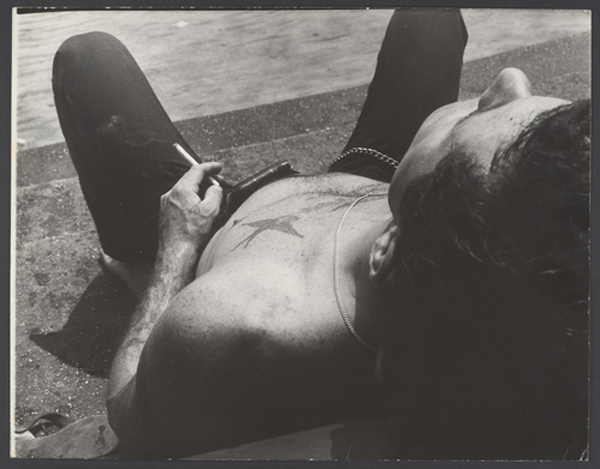

Levinstein’s photos recall the vibrancy of Robert Frank’s urban scenes and the unselfconsciousness of Walker Evans’ hidden-camera subway shots, but with elements of levity and the grotesque. He’s happy to trade unguarded expressions for the instant of surprise, to capture the shock of recognition when making eye contact with a stranger. As a result, Hipsters has the democratic feel of surfing the crowds during a New York summer. Levinstein’s portraits, often taken point-blank, are like catching a fleeting detail while crossing the street, or noticing a reflection in a store window. His affinity for high-contrast tones only heightens the drama. A notorious loner, Levinstein cast himself as a ghostly flaneur, piecing together fragments of a city that seems especially sly and solitary when seen through his eyes. In two works hanging side-by-side, a bloated male torso (head excluded) takes up the whole frame, while in the other, a pair of spindly, disembodied legs can be seen relaxing at the beach.

Given his theme and his predecessors, Levinstein’s photos are refreshingly unsentimental. Class and race are present, but they don’t suffocate under a heavy moral hand, and instead are intricately linked to a sense of place. Levinstein is stingy on details, but the photos are rife with visual clues. Neighborhoods are recognized at an almost visceral level—a young man on a dingy stoop evokes the Lower East Side of the 60s, while a shot of a well dressed woman—nose skyward, pill-box hat in place—provides all the detail needed to know that that the artist has hopped the train uptown. Levinstein revels in the dynamism of neighborhoods, and true to lived city life, his photos evoke the moment of seeing before meaning is registered. Tattooed arms are folded politely behind a squat frame. Couples kiss on the beach. A young hipster preens in a storefront window. This is New York, before there’s too much time to think about what it all means.

If street photography must fight to be more than a postcard to a single evolving second, then Levinstein, like Kerouac and Coltrane in their respective mediums, succeeds by summoning and shaping the force of his cultural moment. His New York is all movement and dirt, rife with the smell and noise of unpolished democracy at a time when technology was only beginning to reach the people. Levinstein recognized this and made it central to his work, approaching the city—and his role in it—with a wink, subtlety but deliberately caricaturing photography’s place in the changing era. It’s a show well worth seeing. I hope the air conditioning works when you do.