-

Parallel Lives: Ayn Rand in Illustration at Winkleman

by Yulia Tikhonova July 7, 2010

A long history of complex interactions between image and text has given rise to a set of expectations about their juxtaposition. Placed side by side, we expect important connections to be revealed, flowing in both directions, as text implicates image and vice versa. In his exhibition Ayn Rand in Illustrations at the Winkleman gallery, Yevgeniy Fiks‘ doesn’t quite achieve the depth we might hope for, though he and Rand’s shared status as émigrés from the USSR does add another layer of intrigue.

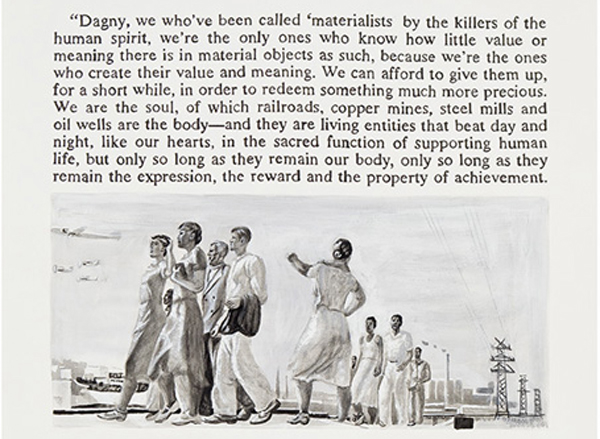

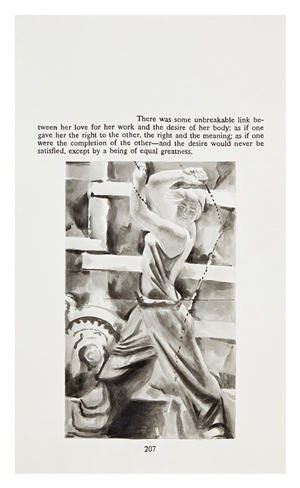

This is a very attractive exhibition, comprised of twenty-two works on paper held neatly in black frames. Each sheet of paper carries an image combining a drawing and a text. The image is dominant, consuming most of the page, whereas the texts are alternately short and long. Not all of the images are centered but float in relation to the edges of the paper. Rendered in watercolor, ink and pencil, each of these graphic studies is numbered according to the pages of Atlas Shrugged where the quotes originate. This ‘bookish’ format is sometimes convincing but it does reveal several arbitrary and simplistic combinations of text and image.

Overall, the texts are libertarian hymns praising industrialization and money. Included are phrases like “We are the soul, of which railroads, copper mines, and oil wells are the body “ or “ …he had no touch of that what people called culture. But he knew railroads. ” These texts are illustrated either by scenes of monumental construction or accompanied by tall, muscular people walking across newly developed landscapes. Fiks combines a quote about “some barefoot bum in some pesthole in Central Asia” with an image of a girl walking through a desolated rural area and clenching books in her hands. Her head scarf frames high cheek bones and almond-shaped eyes. Although these images are likely to be unknown to the Western viewer, the formal congruence between capitalist and Soviet ideologies has been widely studied, and Fiks flirts with simply offering a series propaganda diagrams.

There are several works that raise questions: a portrait of handsome man, open faced with styled hair accompanied by a phrase: “I want to make money.” A bronze sculpture by a Russian officer followed by a description: “He traced in space the sign of the dollar.” We are reminded of Rand’s peculiarly unapologetic promotion of capitalism. There is little humility, irony or (self-) critique when she write on behalf of book’s protagonist John Galt: “I don’t care about helping anyone, all I care about is making money.” Openly stated under normal circumstances this feels uneasy, if sort of comical; at present it sounds positively disturbing. Fiks challenges the viewer to see the extent to which our own ideological precepts mirror those of a previous, more classically repressive regime. Referring to contemporary Russian society, the artist has said that “they think that new money will buy a new happiness.” Thus Fiks uses Rand’s text to gesture towards the Russian nouveau riche, linking the new ideology with the old.

In Ayn Rand in Illustrations the question remains open as to whether Fiks sanctions these ideas in a post-Soviet, post-’common’ and definitely newly individualist consciousness; or whether his images show the dark and oppressive underside of Rand’s brand of individualism. What’s more, by prioritizing the aesthetic appearance of the work, Fiks risks creating just another series of consumer objects, undermining the conceptual labor of his project. In this last respect, though, there does emerge a meaningful contrast between the relative humility of the commodities on display and the caterwauling self-importance of both the Stalinist imagery and Rand’s ludicrous prose. Neither, it would seem, are the stylistic order of the day (the triumph of Rand’s ideology notwithstanding) and, in highlighting their parallel legacies, Fiks does well by his larger project. Still, its hard not to feel that some of the larger conceptual stakes go unappreciated and unexplored.