-

A History of Excellence: Women Photographers at MoMA

by Alice Gregory June 15, 2010

In the January 1971 issue of ArtNews, Linda Nochlin published her now-canonical essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? She must not have been talking about photography. At MoMA’s Pictures by Women: A History of Modern Photography it is clear that not only are there numerous great female photographers; they might be the form’s best practitioners. The show is like a party with an immaculately edited guest list. You look at the exhibition checklist the next day and realize there weren’t many, if any, disappointments. Who was in attendance? In no particular order: Dorothea Lange, VALIE EXPORT, Barbara Kruger, Roni Horn, Sally Mann, Hilla Becher, Cindy Sherman, Diane Arbus, Martha Rosler, Kiki Smith, Laurie Simmons. And those are just off the top of my head, never mind the many compelling works by artists I hadn’t heard of.

You can be certain that the male-only version of this party would be a no-go; a similar show for men only is unthinkable. (Or at least one so identified; there have been many male-only photography shows.) This might seem as though it should raise questions about the efficacy of Pictures by Women, but it doesn’t. The curators – Roxana Marcoti, Sarah Meister, and Eva Respini – were wise in their organization of the exhibition. Unlike Global Feminisms, the 2007 exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, Pictures by Women follows an agenda more historical than it is political. Going room by room or piece by piece, one doesn’t miss the lack of a pointed, loaded critique.

Pictures by Women chronicles the medium’s 170-year history with 200 works by 120 woman artists, culled from the museum’s permanent collection. If you navigate the six galleries correctly (I didn’t the first time), you’ll be following a chronological path from 1850-1995, from Anna Atkins’s delicate cyanotype to Carrie Mae Weems’s color prints superimposed with sandblasted text. The years in between, since the viewer’s progress is both spatial and temporal, abound with repeating motifs. The majority of the work could be described as portraiture, and more specifically still, portraiture of other women. It’s tempting to suspect prescription on the part of the curators. When afforded such an opportunity – to promote womens’ art – why wouldn’t you want to keep perspective and content twinned? And there could be worse conceits, certainly, than offering a tacit relation between portraiture and gender identity. But the curators take their responsibility towards history seriously, and one leaves the final gallery with the sense that the proportion of portraiture of women by women is not at all too thetic, but rather an objective sampling of what women really have been producing for the past 170 years.

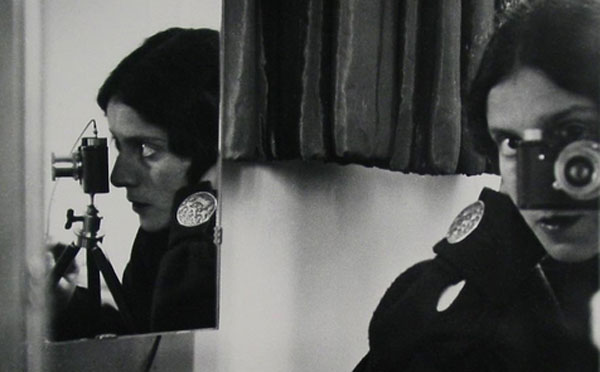

The first gallery is devoted to 19th and early 20th century work and showcases miscellaneous photographic exercises: cyanotypes; platinum, gelatin, and gum prints. The novelty of the medium is still very much apparent here. Dedicated to the rise of modernism in photography, the second gallery includes mostly work by European women from the 1920s and 1930s. Emerging in the third gallery are our heroines of empathetic journalism: Dorothea Lange, with her iconic imagery of the Great Depression and Helen Levitt, with her dramatic scenes of New York City street life.

Often the inevitable inclusion of superstar artists, like Kiki Smith and Cindy Sherman, is token, their chosen work forgettable and merely obligatory. And while this is sometimes the case here, there are surprises – Diane Arbus, for example, whose eight gelatin prints, all hung in a row, serve almost as an advertisement for the entire exhibition. Gone are the Coney Island misshapes and Lower East Side despondents. Rather, we get case studies of women, and though characteristically down and out, their female-ness remains primary: a nudist waitress, a widow, a lady bartender, a woman in a bird mask, a girl in a circus costume. They seem to synthesize their antecedents: at once technically brilliant and intimately documentary.

Other household names, such as Hilla Becher, Leni Riefenstahl, Nan Goldin, and Laurie Simmons, are given wallspace for their uber-representative work: industrial facades; muscled athletes; couples kissing in sickly light; and a belegged dollhouse, respectively. Roni Horn’s annotated, off-set lithographs came as a welcome reprieve from the memory of her lackluster retrospective at the Whitney earlier this year. One of the few exceptions to the general theme of portraiture, Horn’s close-ups of the Thames River are luscious; she conveys the materiality of liquid so successfully that it appears substantive and almost viscous. Taken in 1999, they’ve taken on a new timeliness in light of the tragic events in the gulf.

I returned, twice, to the exhibition’s entrance gallery to reexamine some the first photographs you’re meant to see: 8 of 156 platinum prints by Frances Benjamin Johnson. Originally commissioned in 1899 by the Hampton Institute, the prints were featured in an exhibition about African-American life at the Paris Exposition of 1900. The perspective lends a confusing sense of scale, and the meticulously arranged scenes look like miniature diorama setups. They satisfy that juvenile craving for detailed cross-sections, for modes of life illustrated and for privacy exposed. Here we get a “Class in American History,” in which diligent students study a “real life” Indian in headdress and “Gymnastics at Whittier,” in which children perform calisthenics – the boys in pressed suits and the girls in frilly, white aprons. We see children studying plants and seasons and learning about the history of Thanksgiving.

Johnson’s series, along with Arbus’s prints are the exhibition’s highlights. Both make a case for anachronistic photojournalism, for striking that essential balance between intimate imposition and disinterested remove. The work of Johnson and Arbus serve as mouthpieces for the rest, as questions of identity politics are subsumed into the larger account of history. Though each individual work speaks for itself, one’s experience of Pictures by Women is by definition cumulative, and the story it tells is a narrative one.

1 Comment

Women with Wall Space «

[...] 5. http://rathbonegallery.wordpress.com/ 6. http://idiommag.com/2010/06/a-history-of-excellence-women-photographers-at-moma/ 7. http://katylouisemedia.blog.com/2009/11/10/capture-research/ 8. [...]