-

Unwanted Timelessness: Nick Cave’s Anti-Fashion

by Michael Merriam April 9, 2010

Trash is the one thing people, most emphatically, are not. Though the plight of an individual wearing trash is real, the vision of it seems like a crass and cruel joke. It is beyond sarcasm, more primordial, in its rendering of “regalia.” It is haute couture’s opposite. It is as close an analogue to the work of sculptor Nick Cave as we are likely to get.

Born in the 50s, Nick Cave was raised by a single mother in Missouri. He is black. He learned to sew in Kansas, but after watching Alvin Ailey perform, he realized his calling was performance. You should realize by now that he does not moonlight as an affectedly-gritty Australian pastiche-balladeer, that’s a different Nick Cave.

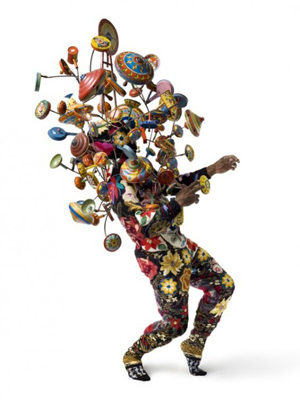

When the sculptor / performer Nick Cave first emerged from obscurity around 2006, fashion and art critics loved him for different reasons. He was still on probation when it came to his relevance, but he had an advantage over his contemporaries because he didn’t bear the curse of contemporary art, namely that it is very easy to walk past most of it. It is not at all easy to walk past one of Nick Cave’s “soundsuits.” Meanwhile, fashionistas would tousle his hair with comments like “What in God’s name is that?” in their blogs and magazines, and they loved him precisely because he was never really one of them. They never imagined that he threatened the status quo, but he does.

Sculptures cannot be shut off like concert recordings, or closetted like gowns. They’re always on, and in a funny sense, however welcome the masterpieces of Michaelangelo might be in the museums of Europe, sculpture is defined by being sort of in the way; even in the case of ceremonial attire, whose DNA Cave says is present in his soundsuits. The ceremonial sculpture / costumes of Africa, whatever their vicissitudes of design and significance, were shaped to tell people: this is not what people look like. Something else is going on. His message comes with a painful twist: some of us have no tribe, and no hope.

Cave is the head of the fashion design department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. That said, the most helpful avenue to take when appreciating Cave is exploring how he is a sculptor and not a fashion designer. As outlandish as his clothes may look, they will not melt into mere novelty. Nor do they submit to the built-in obsolescence of the “fashion industry” as such. In the fashion world proper, a gown speaks for a specific season and month of a certain year, but sculpture is about timelessness.

Fashion is about time, about a human’s participation in a period or epoch. Sculpture, almost the opposite, seeks either to embody eternity, and fully, or to ignore it and win exemption from erosion and entropy. In fashion, gowns are supposed to become obsolete. The failure of a garment to vanish into out-datedness is not a positive quality in fashion circles. Obsolescence is the very paint of fashion. Immunity to obsolescence might sound good to the uninitiated, but it’s playing tennis without a net. You can do it, but your score won’t count, because just as status among fashion writers is determined by “having been there,” fashion is for people who can participate fully in their era. Well, Cave is making the art of people who have been thrown out of their time. It’s about unwanted timelessness, not couture. Like the man dressed as trash, these soundsuits would rather not have to be emblems of cosmic inappropriateness. His gigantic cyllynder of yellow and violet fur is an animal, but it’s an animal which could not have evolved. It cannot offer its species any genetic advantage. It is an animal who cannot participate in biology, as it cannot reproduce, or even die. How is it possible for anything to fall so far outside its proper context? It’s a frightening question for anyone who’s ever felt an awkwardness that’s profound rather than inconvenient, and these costumes dance in that void-space, that kenoma, that flaw in the cosmos that can never heal.

Fashion is about time, about a human’s participation in a period or epoch. Sculpture, almost the opposite, seeks either to embody eternity, and fully, or to ignore it and win exemption from erosion and entropy. In fashion, gowns are supposed to become obsolete. The failure of a garment to vanish into out-datedness is not a positive quality in fashion circles. Obsolescence is the very paint of fashion. Immunity to obsolescence might sound good to the uninitiated, but it’s playing tennis without a net. You can do it, but your score won’t count, because just as status among fashion writers is determined by “having been there,” fashion is for people who can participate fully in their era. Well, Cave is making the art of people who have been thrown out of their time. It’s about unwanted timelessness, not couture. Like the man dressed as trash, these soundsuits would rather not have to be emblems of cosmic inappropriateness. His gigantic cyllynder of yellow and violet fur is an animal, but it’s an animal which could not have evolved. It cannot offer its species any genetic advantage. It is an animal who cannot participate in biology, as it cannot reproduce, or even die. How is it possible for anything to fall so far outside its proper context? It’s a frightening question for anyone who’s ever felt an awkwardness that’s profound rather than inconvenient, and these costumes dance in that void-space, that kenoma, that flaw in the cosmos that can never heal. On the surface, a soundsuit made of disused socks might ask “What happens to the refuse of style?” Nick Cave addresses that but goes further, elevating the question to the level of cosmological inquiry. Because he’s concerned not only with discarded fabrics, but also with the musical instruments thrown from the progress of culture, the sticks thrown out by forests, the most meaningless and forgotten images in dreams. His soundsuits are not only in the way, they make noise and they cannot be ignored. More than that, they insist on causing their audience to rejoice. As indicated by the original title of his show, Meet Me at the Center of the Earth, Cave invites us into a no-holds-barred confrontation with anthropology. He is trying to reveal the proto-ceremony of which all other primitive ceremonies were echoes, the spastic dance of exuberant creatures trying, and failing, to find the true rhythm of matter, energy, and sound.