-

Notes on Art and Ideology in Israel

by Greg Afinogenov February 1, 2010

The Tel Aviv Museum of Art doesn’t host many exhibitions featuring Western artists; the insurance, they say, is too expensive. The same banners on which London or New York museums advertise their gleanings, picked often indiscriminately from widely separated places and times, here, almost exclusively, bear the names of living Israelis. But inside, each exhibition is provided with an explanatory panel written lovingly, and impenetrably, in the typically turgid, and familiar, language of the profession: “Formalizing nature into human body outlines or into its frames of vision is the common denominator of all the details of the exhibited total.” The very seriousness of these panels testifies, not quite mutely, to the museum’s driving passion: its desire to be taken seriously as a legitimate institutional member of the Euro-American art world, and not simply as yet another Holy Land tourist trap filled with Oriental and Orientalized exotica.

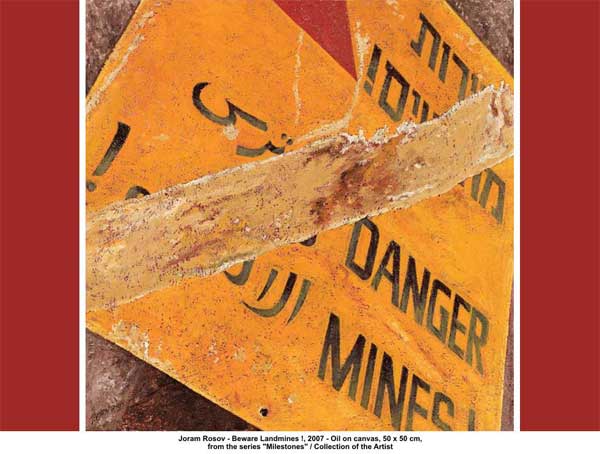

The artists themselves seem to share this thirst for belonging. Alex Kremer (the statement helpfully explains) inscribes his expressionist Israeli landscapes in the common lineage of Western art; the immense signature on his Homage to Mondrian is as much a plea for recognition as a mark of ownership. Aram Gershuni, whose landscapes are muted and precise, aims at nothing less than the recovery of painting—which he considers a lost way of seeing—through “loyalty to the visual experience.” But it is Joram Rozov who, perhaps, gets most acutely and painfully at the central problem. His paintings move chronologically from the copses and valleys of his native region to the gas masks, barbed wire, and military equipment that surrounded him during his stint in the IDF. For Rozov, the movement reenacts his own disillusionment with the Zionist and socialist ideals that animated his parents’ generation and the failure of any comparable new ideals to emerge. If some Israeli artists want so desperately to be taken seriously on their own terms, as participants in the history of Western art and not simply as representatives of an “Israeli School,” it is in part because they sense a deficit in the Israeli national idea.That deficit becomes glaring as one moves from the basement (where Kremer, Gershuni, and Rozov are exhibited) to the upper floors of the museum.

One of the upstairs galleries, for the moment, houses an exhibition of paintings from the collection of David Azrieli, a millionaire architect best known in Israel for his eponymous trio of geometric skyscrapers at the center of Tel Aviv. The paintings revisit, again and again, the familiar touchstones of Israeli conservatism: religion, motherhood, military prowess, the return of the diaspora, the struggle for national survival. From their thematic arrangement a kind of total worldview emerges—self-sufficient and, no doubt, inspirational, but also ossified and incapable of change. None of the paintings even seem to acknowledge that Israel is a country undergoing rapid and unsettling transformations (which are symbolized, not least, by Azrieli’s own skyscrapers). Their most common visual idiom is a vaguely Chagallian, vaguely sentimental image of shtetl life, which serves only to illustrate the process by which an artistic style developed by the marginalized and downtrodden has become the dead matter of institutional art.

There is another museum in Tel Aviv where the problem of national ideology becomes even more starkly defined. It is called the “Museum of the Diaspora,” but, as we see in an explanatory display, it actually denies it: the diagram shows the diaspora’s branches separating off from the original state of Israel only to reunite and lose their particularity with its current incarnation—as if the thousands of Jewish communities still scattered across the globe had suddenly, one summer day in 1948, ceased to exist. The message here, it seems, is that there can be no salvation for the Jews outside of Zionism, and another display drives the point home. The visitor is presented with a panel bearing a selection of historical situations (the French Revolution, the rise of the Nazis, the postwar era, and so on). For each, there are two buttons—one offering the path of assimilation, the other loyalty to Jewish culture and ultimately to Israel itself. Each button, when presseed illuminates the results of the visitor’s choices in an accompanying text, and they are unambiguous. The former choice inevitably leads to disappointment; the latter produces complete self-fulfillment and the satisfaction of participating in a collective nation-building project. Meanwhile, other displays honoring Jewish cultural achievements systematically exclude religious and cultural apostates (like the philosopher Spinoza or the poet Osip Mandelstam) from the ranks of the national elect.

Like the Azrieli collection, the Museum of the Diaspora presents a self-enclosed, self-justifying ideological narrative that at first glance seems remarkably powerful. But this, too, conceals a central absence. After exerting every effort to tell Jews that the state of Israel is their homeland and their destiny, it fails to say anything about what they should do once they have returned to it. The peculiar feature of the Israeli ethnic-religious-national teleology, in other words, is that its telos has already been achieved. Under these circumstances it is unsurprising that it should fail to offer any coherent or satisfying vision of future change, much less a national project amounting to anything more than sheer survival. The only path it appears to leave open is that of purity—the expurgation from Israel of anything that is not Israel. This accounts, of course, for the increasingly inflated perception of the Islamic threat, and at least partially for the continued failure of the peace process: the Palestinians, as the national Other, have the unenviable role of keeping the national Self coherent and unified. But it also has repercussions for life within Israel itself. For instance, as every Israeli knows, there are two kinds of Israeli passport. The first, nominally for religious Jews, has dates written in the Hebrew calendar; the second, for everyone else, has them in the Gregorian. Although holders of the latter are not quite second-class citizens, the threat is constantly looming—which is why a labyrinthine, years-long bureaucratic process of official conversion has been established for those who cannot prove matrilineal Jewish descent. (Ironically, this echoes the efforts of various European countries to control false conversions in the days of the “Jewish question.”)

Thus the internal logic of Israeli national ideology drives, for lack of any other consistent options, towards various kinds and degrees of purging and purification—meaning in this case, as indeed in most others, the elimination of the gap between Israel as a secular political entity and Israel as a religious Promised Land. The problem is not just that this is a metaphysical goal unrealizable in practice, or that it once again fails to imagine a positive future; it is also that it abandons the official vision of 1948 even as it lays claim to it. Built on a series of compromises between uneasy political allies, Israel was conceived in an ambiguity, as both an ethnic-religious homeland and a modern social democracy. To deny the latter aspect is just as ruinous for the carefully-constructed edifice of national ideology as it would be to deny the former: the streets of Tel Aviv and the photographs in the Museum of the Diaspora, which bear the names and faces of Israeli founding fathers who were both Zionists and socialists, cannot simply be revised away. (The collectivist principles of the first kibbutzim, for one thing, are an inalienable part of Israeli national identity.) In short, if religious Zionism represents yet another attempt to give Israelis something to belong to, it must be regarded as an unsuccessful one. And, worse yet, no better alternative seems to be in the offing.

In the end, the creatures who are most at ease in Tel Aviv are the cats. They inhabit every house, every courtyard and dumpster, in families or singly, scavenging and hunting without any regard for human eyes. They show unmistakable signs of their mixed descent, the native Siamese having interbred with waves of once-domestic immigrants from Russia, Europe, and Central Asia. The poet Shaul Tchernichovsky, a minor Zionist culture-hero, wrote famously that “man is the imprint of his native landscape”—and these vigorous hybrids are certainly the imprint of theirs. Like their cats, modern Israelis have something their idealistic grandparents, by and large, did not: a rootedness and a local’s instinct for place. Perhaps that is why the country’s cliffs and scrublands recur so frequently in their paintings; for when ideology ceases to make any sense, only the native landscape remains.