-

Echoes of Ibsen at Vigeland Sculpture Park, Oslo

by Michael Merriam November 2, 2009

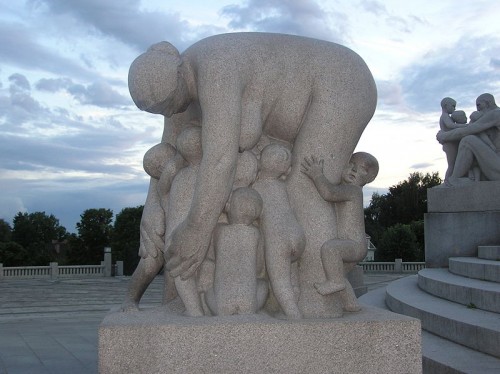

Entering Vigeland’s statuary garden, the visitor is greeted with smooth statues of nude men and women in more-than-intimate contact with naked children. Naturally, an inner alarm warns us not to trust our first instinct; these are not statues of pedophiles. We force ourselves into an attitude of mature appreciation, but as the statues graduate from a naked man holding two children under his arms to more garish and off-putting displays of familial intimacy (two identical twin sisters in a lesbian embrace, a bearded man beating a naked teenager, which I’m told represents a cherished Norwegian ideal of fatherhood) the effect of Vigeland’s passionate misreading of Rodin becomes, for lack of a better word, “icky.”

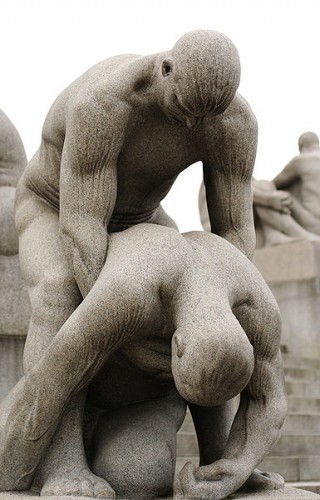

Though it is too easy to giggle at the wrestlers, contorted with exertion, that statue is the exception that proves the rule: while the former was just a naive representation of athletics, the rest of the statues actually deserve our initial knee-jerk reaction. Especially once we get to the man grinning at us while pinching his own nipples. It is impossible to deny the beauty of the statues, but the smoothness Vigeland was expectorating was not solely his own; the Norwegian government, which sought always to be represented as untroubled, non-violent and as a country without trolls, was no doubt the original source. This Will-to-Smoothness was so desperate in Vigeland’s patrons that he used this park to purge it from himself: it is peopled by things which look smooth but are not smooth. There are other parallels with Ibsen, as we shall see.

Where Rodin studied the dynamic of Man and Woman, Vigeland celebrated a fantasy of family with a daemonic muse of something richer and stranger than naïveté. I’ve called this place “The Inappropriate Garden” and have wanted to visit it for years, picturing whole families staring at the statues in puzzlement as I have always imagined the French might stare at Beckett plays. But that, of course, is not how it plays out in practice. The smoothness has caused the statues’ message to slip beneath the consciousness of the observer. They are not transfixed by disquiet, they’re laughing and taking pictures. And they are touching each and every slab of granite.

And it’s natural to want to touch them. They were made to be touched. They possess an appealing texture which owes, really, to the way in which this national commission was completed. Time being a factor, the actual stone-carving was transferred to professional artisans, and, for this reason, and to preserve the granite’s natural sense of volume, simple designs were the most practical. Perhaps this always accompanies expectoration in the arts –a conspicuous practicality that covers for operations of the artist’s unconscious. The utopia imagined here is all about the tactile possibilities within “the family” and the Vigeland – who was famous also for the creation of Hellscapes, and who made money by depicting battles of men against lizards and serpents – is not trying to disguise the tormented machinery therein. He is retching it forth, and the smoothness here does for sculpture what Ibsen did for drama. It’s a cousin of irony: You’re saying these people are smooth?

More boldly, Vigeland is to Rodin what Ibsen is to Strindberg: a version so well-oiled that the machinery of torment, which screeches elsewhere, is silent. To shake Hedda Gabler’s hand is to feel the perfectly warm touch of a human woman. We do not leap back from her as we do from a Strindberg grotesque. Nor do we flee, or even feel, really, the sights and shapes of human heaviness at work in Vigeland’s park. Instead we are left with finely crafted forms, pinching themselves beneath their smooth polish of stone.