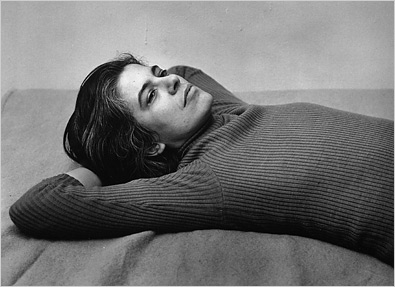

image courtesy of Farrar, Strause and Giroux.

Poems: 1962-2012

Louise Glück

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012

When I was a little bit younger, I thought of Louise Glück as the embodiment of one idea of a poet. She was incisive and dark, she knew how to be commanding, scornful, or tender. She kept her poise in the face of known or unknown terrors —

Look at the night sky:

I have two selves, two kinds of power.

I am here with you, at the window,

watching you react. Yesterday

the moon rose over moist earth in the lower garden.

Now the earth glitters like the moon,

like dead matter crusted with light.You can close your eyes now.

I have heard your cries, and cries before yours,

and the demand behind them.

I have shown you what you want:

not belief, but capitulation

to authority, which depends on violence.

I knew this was not the only way a poet could speak, not the only way a speaker could behave, but it seemed like the essence of a certain kind of ‘poeticism.’ Weren’t these the sort of things a poet should talk about? Shouldn’t a poet address his or her own loves and desperations as nakedly as possible? No matter what dimensions the poem took, she kept faith in the potency of a single lyric speaker.

The author of eleven volumes of poetry spanning more than forty years, both altering the commonplaces of poetry and her work to match time’s arrow, Louise Glück is far more complicated than my imaginary picture. But there is something persistent in the idea of her work and the way it stands apart. It is related to what readers of poetry often call a poet’s ‘voice.’

Part of the pleasure of reading a book of collected poetry, apart from the misplaced passion of the completist, is to watch the development of a poet over time. When a body of work is amassed, it becomes like geological strata. Each layer marks change and development, either gradually or by a rapid turning away from old materials. It is not the only way to examine a body of work, but it is always an attractive one — the narrative begins to write itself.

I’m inclined to read Glück this way for a few reasons. For one, Glück repeatedly explores her personal life in her poems: husbands, children, lovers, and family members are constant subjects of her work. Less directly, Glück is a poet popularly known for creating book-length sequences of poems. Several are organized by a classical myth onto which Glück maps her personal life and poetic voice (Odysseus, Orpheus and Eurydice, Persephone). Others are matched together in more subtle ways. To me, this suggests a constant, and self-conscious, search for unity from within in Glück’s work. It doesn’t seem like a reach to envision an attempt to curate a life through successive volumes — at least there exists an invitation to consider the poet herself (as personality) as the unifying idea behind the body of work.

I think every poet imagines his or her work to be cohere over time in some way, if only by virtue of the fact that the same mind arranges words on a page in both 1968 and 2009. When I look at the disparate books and the multitude of individual poems that cluster in a collected volume, there’s a natural tendency to generalize, to look for the threads that bind the work together and create a consistent idea of the author. In particular, it is the unique containment of Glück’s voice that interests me, the control that comes from her careful circumscription of language and concepts.

Here’s a simplified way of thinking about poetic voice: it is the imprint of a writer’s combined choices of words, phrases, and forms. It is grasped more easily as an entire impression (constructed from our reading) rather than as a specific understanding of particulars. As a reader, I build in my head a model of what kind of person a writer might be, and furthermore what kind of writer that writer might be. This abstracted sense of a writer often leads to the idea of voice, on one hand corresponding to what he or she actually wrote, but also allowing us to imagine what he or she might write in a different context. A sense of voice allows us to imagine what might have been in an author’s burned notebook.

This abstracted idea of voice is different from, but does not necessarily conflict with, the practice of reading a collected body of work like Glück’s. The abstraction runs alongside the particulars — it is a heuristic, a guide to impressions as we accrue more information. As we read, certain details may not match our larger picture. However, an increasingly complex view of a writer’s style does not make the generalization irrelevant. We must always be careful not to confuse the map with the territory.

Glück’s first book, Firstborn, was published in 1968. As one might expect in a first book, the distinctive parts of Glück’s voice are less obvious. This makes the poems instructive by comparison: the later hallmarks of voice are nascent but have not yet been developed. It is also fascinating to see the poet still dabbling with traditional forms of meter and rhyme before largely abandoning them. For example, take the poem Labor Day:

Requiring something lovely on his arm

Took me to Stamford, Connecticut, a quasi-farm,

His family’s; later picking up the mammoth

Girlfriend of Charlie, meanwhile trying to pawn me off

On some third guy also up for the weekend.

But Saturday we still were paired; spent

It sprawled across the sprawling acreage

Until the grass grew limp

With damp. Like me. Johnston-baby, I can still see

The pelted clover, burrs’ prickly fur and gorged

Pastures spewing infinite tiny bells. You pimp.

The hesitant insertion of a few rhymes seems like a reflex indicative of the poem’s larger project: an attempt to completely embody a particular moment. Miniatures like these work to create an image or discrete event, and the clear presentation of this morsel is a successful when it lets us know something new about our reality. It is only ambiguous insofar as the moment in life is an ambiguous one. To capture such a moment requires control — it is important to get the image exactly right as it occurs.

In the need for clarity, the roots of Glück’s distinctive voice can be easily seen, from the tone of scorn to the turn to nature at the poem’s end. There is something both solemn and invasive about Pastures spewing infinite tiny bells. The accusation of You pimp bluntly sums up the conflict of gender, the dual attraction and repulsion that is common in the author’s later books. The final words fall heavily, perhaps unartfully, but it gives an indication of the assertiveness of one of the most distinctive aspects of Glück’s work — of the voice.

In later books, the concreteness of poems like this becomes increasingly rare. Consider the opening lines of Mock Orange the first poem in Glück’s fourth book, The Triumph of Achilles:

It is not the moon, I tell you.

It is these flowers

lighting the yard.I hate them.

I hate them as I hate sex,

the man’s mouth

sealing my mouth, the man’s

paralyzing body —

You pimp can be accessed anyway, without having to create an image that the reader can visualize. The generality of voice and its characteristic gestures become more important than the idea of recreating a particular moment. The generalization often begins by the omission of particulars, creating a world only inhabited by broad nouns: moon, flowers, light, hatred, man, mouth, body. The stripping down of the voice to its essentials becomes an unusual self-consciousness: a voice primarily concerned with voice.

Another related tendency of the first few books is the attempt to embody other speakers in particular poems, often from extremely different perspectives or historical backgrounds. In reality these are less authentic inhabitations of other lives (as a certain kind of short-story writer might attempt) than new garments for the same persistent voice. In a certain sense, this adoption of nominally “other” voices attempts to strengthen the single Glück voice, asserting that its music is trans-historical. A representative example of this is Jeanne D’Arc, from The House On Marshland, Glück’s second book:

It was in the fields. The trees grew still,

a light passed through the leaves speaking

of Christ’s great grace: I heard.

My body hardened into armor.Since the guards

gave me over to darkness I have prayed to God

and now the voices answer I must be

transformed to fire, for God’s purpose,

and have bid me kneel

to bless my King, and thank

the enemy to whom I owe my life.

Like Jeanne D’Arc, it is a compact poem requiring little deciphering of its basic elements. It faithfully represents the story of Joan of Arc as we know it, but is also an obvious cypher for the features of Glück’s poetic language: self-sacrifice, the possibility of an ecstatic message in nature. It may seem reductive to paraphrase in this way, but really it is the lack of ambiguity that makes the poem interesting. Jeanne D’Arc, is an appropriate skeleton for the uncompromising voice, and through history she is more the idea of a person than a physical entity. Accordingly, in her later career Glück commonly favors myth, parable, and fable as the frameworks for poems, looking for narratives that can support an exact, simplified emotional language. The idea of form here and elsewhere is similarly spare, using line breaks more as a convenient pause (a suggestion of breath) than as a formal pattern. The implication of this choice is almost always a kind of urgency, as though the line were trying to break through into unmediated utterance.

This is not to say that this directness is an absolute good, but simply that it is one of the defining elements of Glück’s voice — though her tone softens in later books, it would be hard to imagine her voice modulated into, say, found language or even prose poetry. In her work the limits of lyric are defined, the adherence is essentially religious. Though voice is often recognized in gestalt, we can point to many of the choices made that create Glück’s in particular. The parameters of subject are narrowed down quickly: nature, family, season, myth, love, death. The speech act itself is usually highly charged, manifesting as accusation, confession, or a sharp statement of preference.

This is an old-fashioned universe that has been built up with care. To many modern readers of poetry, those at home with the now-pervasive skepticism of contemporary art, it may seem obsolete, like an obstinate landscape painter who continues toiling, outflanked by more daring peers. A sophisticated reader naturally questions the validity of this voice as an intact, seamless phenomenon exactly because it comes on so strong. The reader is rarely, if ever, provided with the relieving wink that demonstrates that the speech was a performance. Added to this, Glück does little to display her intellectual credentials, consistently favoring the language of emotion. This is just as one might have questioned the claim of an Abstract Expressionist painter to his own personal visual or aesthetic hallmark in the face of something like Pop Art. The interrogation is apt, but is maybe also missing something.

A common expression of this skeptical tendency in poetry has been to raise questions of the incommensurability of language. By putting the power of poetry on trial, writers hope to be vindicated when the world answers in the affirmative. It is interesting that Glück very rarely makes such a gesture. She lies on the opposite end of the spectrum: here the poet declares her absolute power over words. In the final words of Parodos, the first poem of Ararat, Glück makes this explicit:

I was born to a vocation:

to bear witness

to the great mysteries.

Now that I’ve seen both

birth and death, I know

to the dark nature these

are proofs, not

mysteries–

There is some irony here, but perhaps only a touch. Glück’s self-assigned project is to turn mysteries into proofs with her power of vision: she looks to find clarity in poems again, as opposed to the modernist heritage of opacity that still looms over literary discourse. Reading the above words, it becomes apparent how used to reflexive gestures I am, and that their absence is both interesting and risky. I naturally ask myself the question of whether the poem that has come before these final lines can sustain such a deeply serious punctuation, or if there is some clever counterpoint I’m missing. What skeptic of art would even attempt to write such lines? To me, this is the appeal of Glück’s circumscribed voice: instead of reaching outward, she gains power by dominating poetry’s most familiar territories.

The title Parodos evokes ancient Greek theater, so there is some reference to the artificiality of this kind of speech, but only a passing one. The Greeks for Glück have much more resonance as an icon of deep seriousness, where tragedy is the only truthful outcome. The limitations of this approach can be seen in Meadowlands, a collection that joins in the tradition (now nearly as ancient as the source itself) of re-creating Homer’s The Odyssey in a modern context. Odysseus’ journey becomes a map of correspondence for poems that reach into Glück’s personal life, particularly her marriage and the raising of her son. In this edition the distant husband becomes Odysseus, the wary son becomes Telemachus, and the long-suffering wife becomes Penelope. It is perhaps because of the facility of the comparison that the seams show a bit too much. I’m not convinced that the value of The Odyssey lies completely in its similarity to us. Meadowlands is also, not coincidentally, the first book that seriously begins the treatment of the subject of aging. This in itself is not a disquieting additive to a lyric voice, but with Glück it begins to weigh on the poems, blunting their ability to be arresting.

In Ararat, along with The Wild Iris, two of Glück’s most characteristic collections, the power of her voice’s distillation is most apparent. In some ways, we can think of voice is simply an over elaborate way of saying style. In a strict sense this may even be true. Voice, however, has an extra connotation: voice always presupposes a unified consciousness. The lyric poet relies more than any other artist on this conception of a unique, individual voice, a personality behind the screen that breathes life into the artifact. Maybe it is more complete to say that voice is the play between our abstraction and the recognition of a concrete individual who creates his or her own poems.

It is important to make this clarification, as Ararat is the most direct example of what could be called the confessional tendency in Glück’s work, a critical buzzword of poetry now long bypassed. Glück’s personal revelations of marriage and raising a family provide a link to the classic generation of postwar American poets like Lowell, Sexton, and Berryman. It does not seem like a stretch to think that these authors are among the strongest contributors to contemporary poetry’s conventional idea of having a voice. If one goal of poetry is to surprise a reader, one way to do this is to disclose a secret. These poets realized that one way to do this was to literally render up the secrets of their lives. However, any trope is subject to fatigue by repetition. Glück’s poems here are stark and sharp, but they never seem to give too much away about her personal life. Confession is more of a frame for that same raw voice than an attempt to reveal the actual secrets of the author’s life.

In The Wild Iris, Glück’s voice reaches its most intense and most abstract heights. Several of the poems are named either Vespers or Matins, bolstering the intuition that this language is fundamentally a religious language, a language that might have the power to transform through utterance:

As I perceive

I am dying now and know

I will not speak again, will not

survive the earth, be summoned

out of it again, not

a flower yet, a spine only, raw dirt

catching my ribs, I call you,

father and master: all around,

my companions are falling, thinking

you do not see. How

can they know you see

unless you save us?

In the summer twilight, are you

close enough to hear

your child’s terror? Or

are you not my father,

you who raised me?

The collection is constructed around the idea of a garden and its inhabitants. The flowers are able to take up Glück’s voice and thereby become conscious of their own cultivation and repeated destruction. It’s an appropriate framework for mapping the author’s normal concerns. The relationship between lily and gardener easily becomes the relationship between god and man, father and child, or master and slave. Lines like How / can they know you see / unless you save us? are in some ways profound, but are also somewhat contentless. Glück can ask the same question in all circumstances described above. It is the sound of a voice in motion, and the reader concentrates on the sound of the plea rather than the specific question asked.

Between The Wild Iris and Meadowlands it’s hard not to detect a fundamental change. Glück’s early career seems to lead up to The Wild Iris, and that book’s cohesion and stringency is not to be underestimated. Meadowlands, on the other hand, feels like the beginning of a descent. In the later books, I sense the reins being loosened. After the author’s voice has been constricted to the narrowest possible specifications, the only answer that lets a poet keep writing is to expand the range of possibilities. There are many fine poems from Glück’s later career, but they sometimes feel less sharp, more forgiving. Attempts at humor and lightness seem jarring. This is perhaps unfair, but it was the fine-tuning and precision that made the early poems so powerful. Later on, there is more of a complex person behind the poems, but the language itself — simple, dark, emotive — is still equipped to serve the sharpness of the old disembodied voice.

There is both power and weakness in Glück’s poetic language. It is as if a partition is being constructed in order to hold in what is most valuable in poetry and to keep out whatever might threaten these essentials. But circumscription has its costs too: there is a distinct sense of fatigue in reading so many examples of one finely tuned model for poems. The risk of cliché is real when the same archetypical gestures return to poems again and again.

But Louise Glück is not intended to be a model for all other poets. It is difficult to imagine a poet today choosing such radical self-limitation. Perhaps the strain of the Information Age is too great, the perceived need to constantly respond to diffuse surroundings is too demanding. In that case, Glück’s voice is a reminder of the usefulness of a kind of aesthetic discipline, a ruthless desire to seek out the core of the poem. At least in my case, the love song and the image of light streaming through the trees brought me into the world of poetry. We have to be careful in thinking about these most well worn parts of poetic language, the parts that rest on the precipice of cliché. If the changing of the light in the seasons can only become chatter, we must be careful to see that we have not lost the ability to speak of such things at all.

]]>

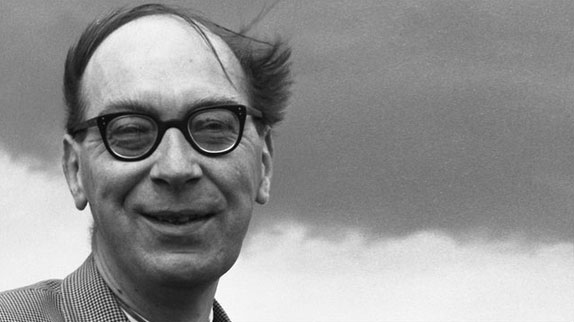

My Struggle: Book One

Karl Ove Knausgaard

translated by Don Bartlett

Archipelago, 2012

In order to become an author, how should a life be? Lurking somewhere in brain or heart of the ambitious writer who seeks to harvest his or her own story, this question seems both obvious and somewhat disreputable. One thinks of, among many examples, the anxiety of Stephen Daedalus, who asks himself by what right can he be transformed into an artist, later finding an obscure answer in his own sense of beauty. It seems that if you have to ask, you’ll never know. Yet the question is overcome time and again, and the künstlerroman is alive and well.

One traditional solution to this question of authority has been the methods of the roman à clef. The proposition of the roman à clef is to mine the material that comprises the author’s life, combing the years to discover the memories and experiences that are most vivid for the author (and those which can be most vividly expressed). This material is reincorporated into the framework of the novel’s fiction, and the author thereby gains distance and the freedom to reshape events as necessary. In this mode, literary form dominates life.

In recent history, the straight memoir or autobiography has held a subsidiary position to the novel. One crucial difference rests in a traditional assumption about the ocean of detail that fills out a life. Life, as it is lived, is full of detail that has no obvious literary value: what we eat on a given day, where we go shopping, the buildings on a walk we take between two places, people we see on the street. The roman à clef is a tool that digests the details that would otherwise fall into a memoir, rearranges them as necessary, weaves them into fabric of literary tropes, and raises them to the status of a universal. The distinction of changing a name, a person’s characteristic tic, or what was served at a meal seems small, but its strength is belied by the persistence of the convention.

However, it’s a convention that raises an equally persistent counter: if the desire of an author is to tell or explain something about the world as it is, how can this manipulated reality be more real than the events as they occurred? Presumably this is part of the appeal of memoirs and biographies: to gain unmediated access to real events. To know about things as they really were and are. Recently it has been suggested that the craving for this type of information has begun to exceed the desire for symmetry and order of the old literary forms.

Karl Ove Knausgaard is a Norwegian author, forty-three years old, and the author of two previous novels. My Struggle is the first translated volume in an enormous, six-volume project of autobiography, subtitled as a novel in the original edition (though this appellation, interestingly, is omitted from the US edition).

This first volume is divided into two sections. The first is largely a series of childhood recollections unassumingly told, spanning the mundane, the humorous, and the poignant. The second part deals with the death of Knausgaard’s father, a solitary and sometimes cruel figure who is constantly present in the young Karl Ove’s thoughts throughout the book. Knausgaard’s father abandons his family and slips into a spiral of alcoholism, leaving the adult Karl Ove and his brother to pick up the pieces when he dies in squalor. These are the two main keys in which the book is played, but the structure is loose, and along the way are digressions, miniature essays, and detours back to the “present tense” of writing the book itself, where Knausgaard reflects on subjects as diverse as contemporary art and the displeasures of raising children.

The books have created a scandal (as well as record-breaking sales) in Norway for the frank disclosure of the secrets, deeply private and occasionally sordid, of Knausgaard’s family and marriages. Knausgaard has himself called the writing of the books a “Faustian bargain.” The outrage comes from a specific cultural context (Americans, for instance, are no strangers to the tell-all memoir), but Knausgaard’s ambitions are clearly international. As the stock of nonfiction continues to rise and the memoir is not only critically accepted, but is regarded as having equal footing with the novel, My Struggle is a particularly timely work. However, the role that My Struggle fills in this shift is not exactly clear.

The most obvious literary forefather is Proust, who Knausgaard acknowledges early on as a generative source: “I not only read Marcel Proust’s novel À la recherché du temps perdu but virtually imbibed it.” However, Knausgaard does not aspire to the perfect architecture of Proust, or his ability to create a disquisition on any object that falls into his field of vision. Nor is he a descendant of the postmodern impulse to interrogate the line between truth and fiction, or to question the sources of truth or the author’s authority. Knausgaard is an aesthete, with an affinity for Old Master painting and some views that could be called conservative. It may be more helpful to think about My Struggle as a contestation of conventions dividing fiction and memoir, but with roots in an older tradition that unironically holds up the power and self-sufficiency of works of art. Knausgaard seeks to destroy, but also to reinvigorate.

For instance, the book opens with an early episode in the interpretation of life’s raw material. The young Karl Ove, aged eight, is watching a TV news report about a sunken fishing boat and suddenly sees the outline of a face appear in the contours of the sea. He runs to tell his father, who remains impassive and uninterested, hammering away at a boulder in the garden. The moment seems almost overripe with metaphorical significance, but Knausgaard deliberately takes care not to exploit the moment in a conventionally “novelistic” way. Instead, he moves to an almost essayistic register, explicating this formative moment in a surprisingly forward way:

Meaning requires content, content requires time, time requires resistance. Knowledge is distance, knowledge is stasis and the enemy of meaning +

From the start, the reader is forced to consider the proposed schema. Knausgaard, both as character and as narrator of his own life is obsessed with the idea of “meaningfulness.” To many readers, taking “meaning” wholesale as a concept may seem rather dubious. Knausgaard’s mission is partly to rescue the term, and he tends to think of meaningfulness as the feeling of meaning. If the impression of meaningfulness is paramount, it seems natural that Knausgaard’s pole stars are childhood and family tragedy, particularly the death of a parent.

By contrast, “knowledge” is considered to be a less valuable way of looking at the world, a way of abrogating experience and replacing it with information. In childhood, everything is meaningful exactly because so little is known, and everything is invested with potential of what things might be. An adult may still have meaningful experience, but it is always mediated by the voice of reason in his or her head. For instance, when Karl Ove’s father dies, the adult narration looks for an explanation for his emotional reaction, only to find that it can’t be properly articulated. In one scene, Karl Ove has boarded a plane to go see his father’s body, and finds that he can’t reconcile his train of thought with his grief:

Everything I saw, faces, bodies ambling through the cabin, stowing their baggage there, sitting down, was followed by a reflective shadow that could not desist from telling me that I was seeing this now while aware that I was seeing this, and so on ad absurdum, and the presence of this thought-shadow, or perhaps better, thought-mirror, also implied a criticism, that I did not feel more than I did +

Of course, shortly thereafter he bursts into sobs and laughter as the airplane takes off, and continues to cry while being aware of the woman next to him stonily staring into her book.

This and other moments in My Struggle are not a retelling of memory as much as a transcription of it, and the experience is strangely compelling. It is an outpouring of anything and everything that Knausgaard associates with a given moment in time, and the feeling of reading it is somehow purgative. Much of its strength comes from the absence of typical novelistic “shaping” of the author’s experience: in the same airplane scene, after his outburst Karl Ove notices the book that the woman is reading and absurdly remarks to himself, “I had read it once. Good idea, poor execution.” His adult reflections are filled with doubts, hesitations, asides, and intellectualizations that circle around events and seem in tune with our own often-uncertain reception of events in real time.

However, in the first section of the book, Knausgaard’s childhood, the outpour competes less with the intellect. His childhood is suburban, middle class, and largely uneventful. Karl Ove plays in an untalented band, slacks off in school, has different short-lived crushes on girls in his class, and sneaks out of the house on New Year’s Eve to get drunk. A great deal depends on the reader accepting the importance of the access to these thoughts as much as the thoughts themselves, as if Knausgaard has presented a diary, one written simultaneously for himself and for you. Here is a typical example of Knausgaard’s attention to the detail of the past:

This evening, the plates with the four prepared slices awaited us as we entered the kitchen. One with brown goat’s cheese, one with ordinary cheese, one with sardines in tomato sauce, one with clove cheese. I didn’t like sardines and ate that slice first. I couldn’t stand fish; boiled cod, which we had at least once a week, made me feel nauseous, as did the steam from the pan in which it was cooked, its taste and consistency. I felt the same about boiled Pollock, boiled coley, boiled haddock, boiled flounder, boiled mackerel, and boiled rose fish. With sardines it wasn’t the taste that was the worst part — I could swallow the tomato sauce by imagining it was ketchup — it was the consistency, and above all, the small slippery tails +

This continues. No memoir is free from an amount of situational detail, which confers a sense of authenticity to the moment as it was lived. The same type of description is commonly seen in a great deal of fiction, a mimetic gesture that helps make things tangible. Knausgaard’s intent is not merely to make a gesture, but rather rather his goal is to fill his account of life with as much of this type of detail as possible. Like automatic writing, it becomes the key that returns the meaningfulness to moments as the sense of proportion between the “important” and the “unimportant” is lost.

The adult Knausgaard implies that this method is what has made the book possible, but he couches this admission in an unusual way:

For several years I had tried to write about my father, but had gotten nowhere, probably because the subject was too close to my life, and thus not so easy to force into another form, which of course is a prerequisite for literature. That is its sole law: everything must submit to form. If any of literature’s other elements are stronger than form, the result suffers +

Knausgaard is only able to complete a book about his father by refusing to reincorporate him into a typical novel. The memories must be exhumed exactly as they are, without the restructuring of a “classic” literary form. But not without form altogether. The torrent of memory requires a supplement, the thoughts of the mature writer, to keep it coherent and give it the form it requires.

It would be a mistake to attribute the interest of Knausgaard’s work solely to its transparency or essential truthfulness. It is certainly not the first work to assume the mantle of complete correspondence between characters as they appear and as they are in the world, while maintaining a loosely “novelistic” structure. For Knausgaard the transparency has a purpose in mind, and relates back to the idea of finding the meaning in things. As the second part of My Struggle begins by recounting Knausgaard’s attempt to write his second novel, the work is lifted into a more rarified aesthetic argument. Knausgaard implicitly acknowledges the somewhat unfashionable nature of this line of thought, aligning his interests with pre-20th century painting and its goal of representation. He writes movingly about a Rembrandt self-portrait he admires, describes his strong but ineffable feelings as he flips through a book of Constable paintings. In these passages he gives more insight into the underpinning of his project:

Those…who call for more intellectual depth, more spirituality, have understood nothing, for the problem is that the intellect has taken over everything. Everything has become intellect, even our bodies, they aren’t bodies anymore, but ideas of bodies, something is situated in our own heaven of images and conceptions within us and above us, where an increasingly large part of our lives is lived. The limits of that which cannot speak to us — the unfathomable — no longer exist. We understand everything, and we do so because we have turned everything into ourselves.

The point of this remark is taken in the previous stream of memory; the intellect has been evaded, at least temporarily, by simply taking up the act of accurate representation, as one might paint a landscape. We can try to have experience without thinking about experience.

Knausgaard doesn’t ask you to identify with the details themselves, but instead to investigate your own private memories and to share in the commonality of having your own unique experiences. How did you feel about your childhood meals? What records did you listen to as a teenager? The feeling of those moments is not based on the experiences themselves but instead an invitation to share in the kind of experiences they are. The effect can be almost hypnotic, as recollection after recollection passes in front of you, almost casual but full with the residue of fact. It is like being let in on a secret, but ultimately the secret revealed is a window into the specific experience of another person.

Yet there is a fragile tension here. Looking for the thread of non-intellectualized experience seems deeply at odds with a work that is willing to ruminate at length on (and quite abstractly) on the search for meaning. At the same time, it doesn’t seem as if the outpouring of memory could survive without these types of essayistic passage to provide context, to situate them in a framework that keeps reflections from simply being an undigested catalog of thoughts. And once the above passage has been read, hasn’t the book’s project of creating meaning by transcription become an instrument of a more reflexive, even intellectual, project?

But this is no great contradiction. The importance of Knausgaard’s work lies in the ability to engage honestly with his subjects: as a thinking, educated person, he would be remiss to suppress the intellectual mechanism that is constantly spinning in his mind. A completely unmediated experience would be a deception, a literary artifice just as deliberate as the taking of novelistic liberties. The objective then is a balance instead of a synthesis, a method of contrast and separation between our thoughts and our experiences that attempts to preserve each.

In the work’s second section Karl Ove and his brother spend a great deal of time preparing the funeral and cleaning the house in which their father died, leaving behind a deep record of decay and filth. As he systematically scrubs the trace of his father form each room, Knausgaard recognizes the inevitability of meaningful experience in any life, and these moments naturally become reincorporated back into Knausgaard’s question of form and meaningfulness. Scrubbing away the layers of decay left by his father needs no intellectual foundation, but an intelligent person can (and inevitably will) provide metaphorical significance for the situation.

Knausgaard bookends the work with some reflections on death, imposing one final boundary of form by meditating on the event in life that, according to Knausgaard, makes its form most apparent:

For humans are merely one form among many, which the world produces over and over again, not only in everything that lives but also in everything that does not live, drawn in sand, stone, and water. And death, which I have always regarded as the greatest dimension of life, dark, compelling, was no more than a pipe that springs a leak, a branch that cracks in the wind, a jacket that slips off a clothes hangar and falls to the floor +

In the end the circle between meaning and form is closed. For Knausgaard, death gives form to life by providing a terminus, a common boundary, just as each inanimate object has its own properties. But moreover, the strength of death as a form lies in its inability to be thought: as much as we’d like to make death merely intellectual, we cannot do so. The ceasing of experience is the definitive sign that we must attempt to hold onto whatever experience in life we can, whatever that life may end up being.

]]>

courtesy of Houghton Mifflin.

Manual of Painting and Calligraphy

José Saramago, translated by Giovanni Pontiero

Mariner Books, 2012

Ardent followers of the late writer Jose Saramago, I’m sure have long noticed a gaping hole in their collections. Until recently his translated work available to his American readership — an oeuvre spanning decades — had yet to include his first novel ever written, first published in Portugal in 1977.

When first released in his native country, Manual of Painting and Calligraphy, did not provoke a following or garner much attention — The Gospel According to Jesus Christ, for instance, sparked a row with the Catholic Church and was censored by the Portuguese government. Manual remained largely unnoticed, unlike the next phase of his writing career, which was filled with prestigious literary prizes, the Nobel Prize in Literature among them.

According to the back flap, a copywriter would have you believe it’s a “brilliant juxtaposition of a passionate love story and the crisis of a nation.” Peripherally speaking, those things happen, but what it really is about is the artist’s existential progression. It’s not so much about love, but of enduring fame; it’s not a protest against a fascist regime, but a meditation on fate. Manual is not a manual in the literal sense, but closer in kin to a journal, written by a sardonic portrait painter under the pen name H.

Diary-like in its construction, it also shares components of other literary genres. H explores writing autobiography, along with mini-profiles of other artists, and by including a letter from a scorned lover, even tries his hand at some minor scrapbooking. Though formally trained, H is mistrustful of his ability to paint a lifelike portrait of his subjects. He muses, “[I turn] to writing without knowing its secrets,” paradoxically, in the hope to unveil those very secrets that separate technically skilled painters from actual artists. Manual is in fact, the anti-instructional guide — the titular irony underscored by H’s fervent autodidactic approach to writing.

His clients’ likeliness isn’t the only thing that’s revealed in his portraits. H claims, “anyone who paints portraits portrays himself.” Like strolling into a carnival tent of funhouse mirrors, each portrait renders a caricature of a fraudulent painter at a philosophical fork in the road — provoking his increasing desire to create a “truthful” portrait — one that is a faithful representation of the sitter and the painter. He likens the experience to “asking a psychoanalyst to take interest in a patient just a little bit further, which could lead him to the edge of the precipice and his inevitable downfall.” His plunge into the abyss is his nearest hope towards attaining the form of salvation he’s looking for — letting go of learned techniques and embracing unfiltered intuition.

Manual leaves Saramago more exposed than what is characteristic of the writer. Biographical elements are deeply embedded within its pages. His experience in Lisbon under Salazar’s dictatorship mirrors H’s own. Both men came of age, and grew well into it, while grappling with livelihoods in constant danger of being easily extinguished by a tyrannical government at the sign of any infraction. During particular heady meditations their voices appear to coalesce into one, and I wonder if we are actually glimpsing the pages of Saramago’s journal, when passages like the particular following lament:

If the straits of Tagus are located where I hoped to find India, will I be obliged to relinquish the name Vasco and call myself Ferdinand? Heaven forbid that I should die en route, as always happens to the man who fails to find what he is searching for in life. The man who took the wrong route and chose the wrong name +

Strangely, H’s emphasis on biography appears to be his prescribed antidote for these ill-fated men, the tragic victims of fate. Though crude, through sheer cleverness, he more or less achieves what he champions as a “freedom to be won” by filling reams of paper with a “written” portrait, he’s created a work guided by faith alone. In essence, he’s put on a blindfold, climbed a chair, and has fallen backwards trusting someone will catch him, which is the most honest piece of art he’s authored. If a painter portrays himself painting, it can also be said, anyone who writes, writes himself. He’s casted people from his life as characters within his narrative while he remains the unadulterated protagonist.

H has picked the lock and freed himself of his own limitations as an artist by writing the skeleton key. By relinquishing his christened name in favor of his initial H, he proves he is neither Vasco nor Ferdinand, philosophizing:

To give…a name is to capture him at a given moment in his earthly journey, to immobilize him, perhaps off-balance, to present him disfigured. A simple initial leaves him indeterminate, but determining him self in movement +

Names denote limitations and impose boundaries, and this, is a story about grown and rebirth.

H self assesses, “What do I want? First, not to be defeated. Then, if possible, to succeed.” This also appears to be Saramago’s ideal for Manual. It may lack tidiness, emphasized especially by H’s pedantic ramblings, (“Careful! What have I just written? Paint the saint. I know exactly what I am about to do, but could anyone reading these three words know it?…But what does it mean to pain the saint?” gives you an idea) but Manualneither ends in defeat for either man. By the last page H’s papers reveal a portrait of an artist whose reflection is crisply and clearly defined than any portrait painted.

As far as first novels go, it’s an endearing snapshot of the author, not as a young man, for he wasn’t young when he began writing professionally, but as a young writer — exhibiting exuberant energy in his prose, yet lacking matured restraint only experience can teach to pull back when necessary. However, it’s this vulnerability that results in Manual being a far more intimate read than some of his later work. If you’re an admirer of the late writer, Saramago slightly undone makes it worth the read.

]]>

courtesy of New Directions Books.

The Passion According to G.H.

Clarice Lispector, translated by Idra Novey. New Directions, 2012.

Why This World: A Biography of Clarice Lispector

Benjamin Moser. Oxford University Press, 2009.

The Portuguese word saudade appears three times in Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector’s 1964 novel The Passion According to G.H. There is no English-language equivalent for saudade, and its meaning is interpreted in two different translations of the novel — the 1988 version by Ronald Sousa and the new edition by Idra Novey, released by New Directions in May — as follows:

“I shall have to bid a nostalgic good-bye to beauty”

“I’ll have to bid farewell with longing to beauty”

“A suffering with a great sense of loss”

“A suffering of great longing”

“I long to go back to hell”

“I miss Hell”

Several years ago I had dinner with a group of non-English-speaking Brazilians at a Cuban restaurant populated by men in hats drinking alone, each at their own small table, listening to old mambo music and looking into their cups. “They have saudade for Cuba,” observed one of my Brazilian friends, and everyone nodded. They were disappointed to learn that the concept is not articulable in English. “If Americans were ever forced to leave their country,” offered our party’s eldest from a pensive slump at the head of the table, “they would have a word for saudade.”

The English translations are not wrong, they’re just incomplete. saudade is indulgent, cinematic, a satisfying wallow; it’s like tonguing a canker sore to explore the pain and make sure it’s not gone. The Passion According to G.H. — the story of a philosophical and spiritual crisis brought on by the guts of a dying cockroach — is all saudade, a woman spelunking in her own existential ache.

G.H., roach-killer, is a reasonably successful sculptor, financially independent and located in a sort of neutral place — competent but not excellent, accomplished but not extraordinarily so, a person others refer to as “someone who does sculptures which wouldn’t be bad if they were less amateurish.” On the day in question, she finishes a leisurely breakfast alone and spends a pleasant idle stretch rolling the soft insides of a loaf of bread into little balls with her fingers. As she rolls she contemplates the satisfaction of cleaning the room once occupied by her recently former maid. She expects filth and stacks of old newspapers, but when she enters, she finds the room spotless, hot, bare, and loathsome. The maid has left a simple charcoal drawing on the wall, which G.H. interprets as an expression of her hatred. From the depths of a parched wardrobe, a cockroach ambles into view. G.H. despises cockroaches.

She can’t leave the room. She wants to. She keeps recalling a recent newspaper headline, “Lost in the Firey Hell of a Canyon a Woman Struggles for Life.” She slams the door of the wardrobe on the roach, but not hard enough. It looks at her, trapped and broken but not quite dead. It occurs to G.H. that she is disgusted with herself, not for nearly bisecting the roach, but because she has, she says, thus far lived a life of “not-being.” “I always kept a quotation mark to my left and another to my right,” she says. “An inexistent life possessed me entirely and kept me busy like an invention.” She is nothing more than the initials engraved on her luggage. This empty comfort is what G.H. is talking about when she says “I’ll have to bid farewell with longing (saudade) to beauty.” Because “loving the ritual of life more than one’s own self– that was hell,” which is what she means when she says, “I miss (saudade) Hell.”

G.H. discovers that she has never really looked at a roach, and contemplating this one, she understands another great saudade of human existence:

The mystery of human destiny is that we are fatal, but we have the freedom to carry out our fatefulness: it depends on us to carry out our fatal destiny. While inhuman beings, like the roach, carry out their own complete cycle, without ever erring because they don’t choose. But it depends on me to freely become what I fatally am. I am the mistress of my fatality, and if I decide not to carry it out, I’ll remain outside my specifically living nature.

So what is G.H.’s “specifically living nature,” which she tortures herself by avoiding and tortures herself to find? She never really says. But the terror underlying her tale is like a sheet of ice beneath the carpet, a murky, self-loathing dread of sitting around rolling bread balls while time slides comfortably away, and a horror with allowing herself to be undefined. And then there is euphoria that comes with shutting oneself away and staring down the roach while “white matter” spurts from its crushed shell — this, in fact, is the only way to become something beyond the empty mark of one’s initials.

G.H.’s crisis so acutely captures how I feel about writing that the whole thing, to me, is like a frighteningly internalized Room of One’s Own. Maybe in 1928, when Virginia Woolf was writing, a quiet room and a little financial security were the primary concerns, but once those are in place your main obstacle is yourself, your doubts, and the daily machinations of your petty, lovely life. G.H. is cursed with too much comfort, too much choice. With a whole apartment to herself, her “room of one ’s own” is her maid’s. “The plays of Shakespeare are not by you,” Woolf wrote. “What is your excuse?” She was kidding, but only sort of. G.H. has no excuse. She longs to be distracted by the telephone, which she has taken off the hook, and complains, in the midst of a thicket of philosophical tangents, that if she had known what was going to happen that day in the maid’s room she would have brought some cigarettes. When the book’s conclusion is in sight, she wraps herself in parentheses and says:

(I know one thing: if I reach the end of this story, I’ll go, not tomorrow, but this very day, out to eat and dance at the “Top-Bambino,” I furiously need to have some fun and diverge myself. Yes, I’ll definitely wear my new blue dress that flatters me and gives me color, I’ll call Carlos, Josefina, Antônio, I don’t really remember which of the two of them I noticed wanted me or if both wanted me, I’ll eat “crevettes a la whatever,” and I know because I’ll eat crevettes, tonight, tonight will be my normal life resumed, the life of my common joy, for the rest of my days I’ll need my light, sweet and good-humored vulgarity, I need to forget, like everyone.)

A double saudade — one lament for the life before and another for its inevitable return, on one side a desperate need to shut the door and articulate something important and on the other a positive mania to return to the vapidity of life as usual the second it is done. “It’s such a high unstable equilibrium that I know I won’t be knowing about that equilibrium for very long,” says G.H., “the grace of passion is short.”

In other words, a writer’s struggle, the author’s experience fitted onto a fictional character. True, G.H. was poor once — the roach horrifies her, in part, because it brings back a childhood memory of lifting a mattress to find a black swarm of bedbugs — but so was Clarice Lispector. As an adult Lispector, like G.H. was well off, the wife of a diplomat with whom she traveled and lived in three countries before divorcing him and returning to Brazil in 1959. She had two sons and all the obligations of the matriarch of a family of stature. Her husband didn’t think much of her work. Surely G.H.’s fight to articulate herself is Lispector’s struggle to write books, maybe even this book. But this is not so obvious to every reader. A recent essay likens G.H.’s fear of an unarticulated self to the feelings of gay couples unable to wed, and another notes that it is a precise expression of the conflicting desire to be known yet anonymous in the age of Twitter and Facebook. Benjamin Moser, who oversaw the new translation of G.H. and wrote the excellent Lispector biography Why This World, reads G.H. as the story of a Jewish mystical crisis, asking and answering “all the essentially Jewish questions: about the beauty and absurdity of a world in which God is dead, and the mad people who are determined to seek Him out anyway.”

We are all correct. Remember that this is the passion according to G.H., or in Portuguese, segundo G.H., which comes from the Latin secundus, or “follows,” and is similar to saying “as interpreted by.” But G.H. herself offers very little interpretation. She specifies only passion, the map of an emotional state, into which we intuitively build the architecture of our own obsessions. And G.H. obliges everyone’s interpretation. It says yes to us all.

This malleability is the book’s most striking and brilliant feature, and is a function of Lispector’s insistence on the inadequacy of words. “The unsayable can only be given to me through the failure of my language,” says G.H. “Only when the construction fails, can I obtain what it could not achieve.” Lispector’s writing is elastic and refuses to point at any one thing, it gathers into puddles of unspecified shape. You must swim through vague digressive paragraphs clinging intermittently to the buoys of G.H.’s philosophical aphorisms. She tries your patience. But the resulting “story” forms itself around whatever questions it is asked. We find that it is touchingly personal. It is about the fears that plague us; it names the saudade we feel.

The temptation is to use Lispector’s biography to prove the truth our own understanding, to fill her words with the shape of the woman herself, confirming of the meaning of G.H. segundo us. Those of us who love Lispector’s books are deeply in Moser’s debt for the sheer amount of detail in Why This World. The only thing wrong with the book is that it’s too much fun, and it has enticed nearly every Lispector critic since its publication to spend a great deal of time pinning the facts of her life to her work. But the facts distract us from the prose itself, and sometimes they are no help at all. In real life, Lispector disliked being compared to Virginia Woolf. She said she had never read any Woolf until after she had published her first novel, and besides, “I don’t want to forgive her for committing suicide,” Lispector wrote. “The terrible duty is to go to the end.” Lispector’s end came in 1977, of ovarian cancer, and even this simple fact is interpreted by her fans as a literary event of great yet varied metaphorical significance. Moser says Lispector’s death was “spookily appropriate,” given “a lifetime of writing about eggs and the mystery of birth.” (I don’t deny it. “That roach had had children and I had not,” muses G.H., who herself has had an abortion.) Lorrie Moore disagrees with Moser. “[H]er illness seems less significant as a figuration,” she wrote in the New York Review of Books, “than it does as a disease that disproportionately afflicts Ashkenazy Jewish women. In other words, despite everything, a Jewish death.” But I must point out that the fact of Lispector’s death was foretold by G.H., who says: “One day we shall regret those who died of cancer without using the cure that is there. Clearly we still do not need to not die of cancer. Everything is here.” In a characteristically weird way, Lispector died of what she didn’t need to not die of, a cancer that was an omission of desire for life, or at least for a different death. Moser tells us that Lispector, in a taxi on the way to the hospital where she died, told a friend that “everyone chooses they way they die.” But I don’t need to know this. I knew G.H. first, and she shouldn’t have to live according to Lispector’s life. Lispector can die according to G.H.

]]>

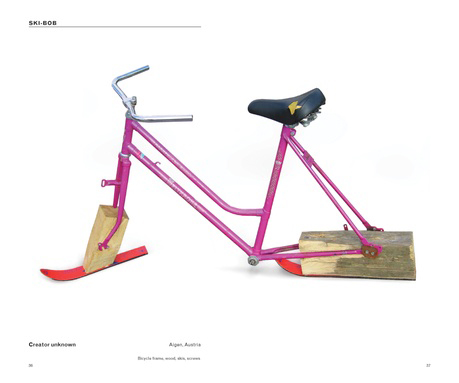

image from Arkhipov’s ‘Home-Made Europe,’ courtesy of FUEL.

Home-Made Europe: Contemporary Folk Artifacts

Fuel, 2012

Determined to hang a picture on the wall but lacking a hammer, I recently assigned half a loaf of bread to do the job. At first it felt awry and a little Chaplinesque, but the loaf had spent the past few weeks in a neglected corner of the pantry and had become so stale that it had taken on the characteristics of a small but heavy rock. The nail sailed into the wall after one hit and I found myself eyeballing this lump of ossified dough and praising it as a marvelous creation. Who knew it could defy its fate and re-invent itself in the spirit of necessity, emerging as an unlikely and spontaneous hammer? Of course the bread hadn’t done anything but follow the logic of its starchy molecules, but there it was, in a context where the appropriate tool was missing and any solid, weighty, cudgel-like implement would do.

I wondered if my bread-hammer would qualify for Vladimir Arkhipov’s Home-Made Europe: Contemporary Folk Artifacts. Upon reflection, probably not, but I did feel as though I’d touched, however pathetically, on a nerve that dictates many of the inventions and utilitarian mash-ups documented in the book. If the title is familiar it’s because this is the second of its kind, the younger sibling of Home-Made: Contemporary Russian Folk Artifacts (2006). I remember picking up this book with a friend, and sensing the air and aura of a rare find, even though we were in a multi-story bookshop. It is difficult to know why a book emanates that kind of vapor. In this case, it seemed to have something to do with how it had organized and compressed a universe of stuff. How it had observed, and through that observation attributed value to what was previously obscured. Or, was it just how it quietly parted that vast and turbulent sea of crap in order to demarcate an agenda? Does Arkhipov’s latest version achieve a similar feat? I want to nod and give a phlegmatic yes, but the truth is I’m still vacillating.

The natal conditions for Arkhipov’s category of ‘thing’ are more or less explicit: the prevailing, mass-produced object is absent so an unlikely material, item, bit or gobbet is recruited and rubbed with gumption. We’re probably all familiar with this kind of greenhorn ingenuity, where objects are jammed into reality in the same way you might fashion an ersatz bathplug out of a scrunched up plastic bag (this works), or appoint a spent piece of chewing gum to stick a photograph on the wall (this sometimes works, depending on the brand of gum). Arkhipov’s biography indicates that he probably knows a thing or two about trying something out and seeing if it sticks; having worked as an engineer, a physician and now as a self-taught artist. He has maintained the ‘Post-Folk Archive’ or ‘Museum of the Handmade Object’ (two iterations of the same project) since 1994, of which the two books draw from. If you’re willing to pilot through a puzzling website where the archive continues to grow google “powerstrip Arkhipov”.

Back to the book. It contains 221 examples of home-made-hand-made artifacts from around (mostly rural) Europe, and is usually accompanied by the maker’s passport-sized photo and a brief account of how the object came to be, which Arkhipov records on a dictaphone and then transcribes. In this way, the book has a pace similar to a collection of show-and-tells or untidy short stories. The pages are peppered with anecdotal vim, colloquial commentary, complaints and taciturn (occasionally bordering on frustrated) explanations about how the object functions, its history, why it exists at all. This makes for an eccentric assortment of talk — the artifacts are commonly described in a flat and direct manner that comes from earnest, often slipshod, conversation.

There is a ‘summer shower’ in Yuzhonye Butovo, Moscow, as recounted by Boris Petrovich:

There’s not much to tell, it’s a summer shower. Well, the man who lived next door worked as a bus driver. There were loads of old broken bus doors at the bus depot, doors that had been written off. So he decided to use them. He put them together here, fixed them together to make corners, like this — so they stand up, they don’t move. They’re heavy, sturdy, they stay up. That’s it…

A toy machine gun (one of the many imitation weapons for kids in the book) from Staritsa, Tver region, Russia, begrudgingly described by its maker Petr Naoumov:

I’m not going to talk about it, what’s to tell anyway? It’s obvious isn’t it? I made it for my son to play with. He likes it…I made it with whatever I had at hand. The trunk is from when we knocked the apple trees down, there were branches lying around. There’s some plywood, the wheels are taken from his own pram, from when he was very little.

And who could ignore the marvelous verisimilitude and craftsmanship of Olga’s dildo?

Well I was stupid, I stole something and they locked me up. I was in prison in the Yaroslavl region [Russia], sent down for five years. We used to sew slippers and mittens, I was young so I was frisky. And where’s a girl to go without a man? It was real torture, you’d start humping any stick. A carrot or a cucumber – everyone does that. And what happens when you want one and there aren’t any around? So I found a piece of rubber and used that. Fuck knows what kind of rubber it is, I just carved it up with a knife when nobody was looking. I still keep it in case it comes in handy again!

Or, changing the focus to another tool of necessity — and possibly one of the most historically compelling and remarkable objects in the book — a spoon made by Ivan Kuzmitch Satchivko in Kiev, fashioned just after the second world war following the Nazi occupation of Ukraine:

My father worked in a factory, where he did reconstruction work. When any spare metal came along, he made things with it for family and friends: a plough of some sort or spade — people didn’t have anything, you see. Yet there was a lot abandoned, broken military equipment left in the fields. One day some relatives from the country brought him some aluminum from a downed German bomber, and asked him to make useful household things out of it: combs, spoons, mugs, bowls. Nothing went to waste, nothing was left of the wreckage when he’d finished. We used the crooked saucepans and frying pans that my father made for a long time. Then, when our living conditions improved, we threw everything away.

Except the spoon. The spoon survived. It’s objects like this that seem to challenge our definitions of design and what it really means to grapple with necessity and the material world. There is a sense of fate-redirected here; a crashed German bomber with all the weight of its history (the ideology behind its production, the workers who made it, its purpose, its pilot, its downfall) converted, eventually, into a domestic utensil. Sitting at this Ikea desk on this Ikea chair it’s difficult to completely comprehend that kind symbolic and material narrative, where an object has tumbled from a radically complicated past and context but simply exists as a spoon — used like any other. If we can confidently say that history is altered by objects, we also have to admit that objects alter history: they give a shape, and entangle history with the everyday.

This is what many contemporary artists spend their time doing. All you have to do is peer down the line of institutionalized ready-mades (look, for recent examples, at the work of someone like Gedi Sibony or Tom Sachs) to see an entire gang of objects revered for their ‘impoverished’ style and the way they ‘blur’ the line between life and art. I’m using quotation marks here because the problem is — and always has been — life doesn’t really care about art. How could it when it comes before it and remains after it? Art and life are in a perpetually unequal relationship and it’s clear which one wears the collar. In Arkhipov’s brief afterword he wonders about this, asking:

According to Aristotle, Art is an imitation of reality, so couldn’t creating the reality preceding this imitation itself be an important earlier stage of the artistic process? How is this creativity subtly different from Art?

It’s a good question. Phrased as a riddle it might sound something like: what comes before art, which could in fact be art, but is not art? Whatever the answer, Duchamp really screwed us. However, the objects collected in this book are semi-separate from this conundrum precisely because they inhabit a larger world, the world of use (dildo, toy, spoon, post box). This is what Arkhipov is seemingly obsessed with and ultimately where the power of his project resides. By simply paying attention to these used things — things outside professional categories or putative disciplines — he has managed to show some of the bits and pieces that escape standard notions of contemporary art and design and the slick belch of consumer goods. So, you might say that these objects sit in front of or beyond the canon of art and design simply because they ignore it.

And what about the proximity of these artifacts to DIY? Let’s be clear. There is nothing radical about Do-It-Yourself hobbies occurring on the weekend or in the garage of the eponymous retiree. It is the British artist Jeremy Deller, in the forward to Home-Made Europe, who is careful to separate this species of object from that of DIY, a hobby, he writes, “that seems so pleased with itself”. Deller, who has maintained his own ‘folk archive’ since 2000, views Arkhipov’s objects to have “a healthy disdain for traditional DIY values of finish and professionalism.” Indeed, DIY culture has never strayed too far from a well-stocked shop. Its emergence in the 1950s coincided with a wealth of new and available materials, hand-held electric tools and the introduction of the VCR (significant for the stream of instructional and home improvement videos). Add to this the baby boom, the value placed on home ownership and self-improvement and you have a recipe for varnished kitchen cabinets and birch wood spice racks, but that’s about it.

In honesty I’ve got nothing against this kind of weekend construction, but the value of this book seems to rely on a clearly defined area of creative production: design in the face of a lack of materials rather than an abundance. It is here that I think Home-Made Europe might lose some of its grip. While the examples I cited before come from Russia and the Ukraine, the book documents objects from eleven other countries around Europe. In Austria we find a basketball hoop fashioned out of a long piece of wood and an old bucket, in England we see a ‘yeast paddle’ made from an old frying pan (for stirring home-made beer), in Switzerland we admire a three-dimensional ice-cream menu carved from pieces of wood, in Italy we find an Italian dog sitting on a make-shift doggy bed. These objects are compelling, no doubt, but they also lack that ingenious brutality born from necessity that most of the Russian objects seem to possess.

This might be why Arkhipov’s first book, which focused solely on artifacts from Russia, came across with more urgency; a potency where the artifacts so perfectly represent the countries history of just not having that much. Perestroika — the policy reforms enacted by Mikhail Gorbachev in the 1980s that marked the dissolution of the Soviet Union and signaled a time of great absence — is mentioned (often casually) by many of the Russian contributors. Spreading across Europe in the recent version, it’s harder to get a sense of what these objects reveal beyond their individual inventiveness, but maybe this is enough. That we are in the midst of the European soverign-debt crisis goes unmentioned in the book, but is worth pondering. Can objects like these, no matter how funny or silly, take on the symbolic weight of the European financial debacle? What are the patterns, reoccurring contexts and solutions to common material problems? Can we read these artifacts as abstract yet physical by-products of global and national policies and politics? Or, does this merely patronize the singularity of their designs?

There will be those who flick through Home-Made Europe and chuckle at the zany forms and collaged crudity, relegate it to the category of loony-thingamajigs or show it off on a coffee table as a trophy that shines with enough obscurity and folkish charm to be deemed ‘interesting’. While the format and tone of the book certainly lends itself to this kind of fate (it is essentially a picture book) appreciating it solely in this way, I believe, misses the point. What we should notice here is the kind of ingenuity that is possible when confronted with a material world in fragments; a broken leg but no crutch, a heavy coat but no hanger. On occasions like this, it seems that you either become a designer or you don’t.

]]>

How Should a Person Be?

Sheila Heti.Henry Holt and Co., 2012.

Writing on the French artist Sophie Calle’s True Stories (or Autobiographies), the art historian Rosalind Krauss asked, “Under what circumstances are stories true?” An ongoing project begun in 1988, True Stories is comprised of autobiographical texts narrating significant moments in Calle’s life, juxtaposed with quasi-anthropological photographs of related objects (and more recently, with the objects themselves). Drawn from the artist’s memories, fantasies, and dreams, Calle’s stories are true to the extent that she has claimed them as her own. Yet, taken as a whole, these ‘truthful’ fragments form an unwieldy composite portrait that can neither be considered wholly accurate, nor entirely fictional — a work of art is always, on some level, constructed, even if cast entirely from life.

In the recently released US version of Toronto-based writer Sheila Heti’s novel How Should a Person Be?, a revised edition of the novel she published in Canada in 2011, there is a disclaimer in small print at the bottom of the colophon:

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel either are products of the author’s imagination are used fictitiously.

Billed as “a novel from life,” How Should a Person Be?’s protagonist is a recently divorced twenty-something writer named Sheila, whose biography conforms more or less exactly to that of the author. Much of the book focuses on the relationship between Sheila and her best friend, a painter named Margaux, who is likewise modeled on Heti’s real-life best friend, the painter Margaux Williamson. The majority of the characters are similarly recognizable as members of Toronto’s art and literary scenes. Large portions of the novel take the form of emails and transcripts of conversations recorded by Heti, ostensibly reproducing her own words, as well as those of Margaux and others, verbatim. That a novel consists of fictitious characters, organizations, and events would normally seem self-evident, but in How Should a Person Be? such a categorization becomes somewhat more ambiguous. Under what circumstances are stories fictional, if the people, places, and events they depict might equally be recognized as fact?

When asked about the difference between herself and the character Sheila of the novel, Heti answered: “I’m a person and not a piece of paper…A person is not a static thing, or a bunch of words.” The novel calls attention to this distinction throughout, directly addressing the tension implicit in creating a “novel from life.” Heti does not merely use her repository of recorded and transcribed material as the model for the book, but foregrounds the process of collecting it, narrating the novel’s own formation: Sheila begins taping her conversations because she is struggling to write. Commissioned by a feminist theatre company to write a play about women — a subject she professes to know nothing about — she hopes that analyzing her own real-life dialogue will provide insight into how to give her characters weight. Though the play is the pretense for her obsessive documentation, Sheila’s inquiry soon takes on a life of its own. Realizing, after a trip to Miami with Margaux for Art Basel, that her research into the lives of those around her is more interesting than the fictional people she’s been attempting to make lifelike, Sheila begins transcribing the recordings, along with her own recollections of events: “It wasn’t my play, but it felt good….I felt closer to knowing something about reality, closer to some truth.”

It seems significant that Calle’s work looms large in How Should a Person Be?’s most obvious literary precursor, Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick, a novel in which the author similarly mines her own life, leaving proper names in tact (I Love Dick also narrates its own formation). Equal parts confessional and analytical, Calle’s work seems to be the conceptual forbear for Heti’s novel. Through a practice that turns a documentary lens to the artist’s own subjective experiences, Calle’s life is not only her source material, but her medium: she documents her actions, but also acts so that she can document.

For Krauss, the structural principle guiding Calle’s work — what she calls its “technical support” — is photojournalism, a kind of forensic research into her own life, as well as the lives of those she encounters: for The Address Book (1983), Calle photocopied the contents of an address book she found on the street and reached out to the contacts listed within, inquiring about the owner’s character, interests, and routine, ultimately publishing the results of her investigation in the French newspaper Libération. Likewise, Heti cannibalizes the words of her friends, transforming those around her into subjects.

When the owner of Calle’s address book caught on to the project, he retaliated by publishing a nude photograph of her in the same newspaper, an attempt to match his own feelings of violation. In the novel, Heti’s subjects also push back against her treatment. Though they consent to being recorded — as Margaux states, “You know I have more respect for your art than I do for my own fears” — Sheila’s transformation of their friendship into an object of study is a constant source of tension: “I’m doing a lot, what with letting you tape me, but — boundaries, Sheila. Barriers. We need them. They let you love someone. Otherwise you might kill them.”

As Calle noted in an interview with Heti in The Believer, where the latter is, appropriately, the Interviews Editor, the question of truth in art is never straightforward:

The truth? Which truth? Your truth? Their truth? The truth today at two o’clock in New York, or the truth tomorrow at five o’clock in Paris? The truth now that it’s raining? What does it mean? Me, I would say things happened or didn’t happen, but I would not say that’s the truth.

This shifting definition of “truth” seems equally applicable to Heti’s novel. Though she insists upon the distinction between its characters and the actual people whose lives she borrows — a person is not a piece of paper — it is impossible to divorce the two entirely, as Heti surely understood when she chose not to assign her friend-characters new names. Heti has regularly cited the influence of reality television shows on How Should a Person Be?, particularly docudramas like MTV’s The Hills. The comparison is apt, at least on the level of form: we can say conclusively that the events depicted are real to the extent that they happened, and someone recorded it, but the final product is artificial — fiction composed from fragments of life.

]]>

Sontag, 1975 by Peter Hugar. Courtesy of The Susan Sontag Foundation.

As Consciousness is Harnessed to Flesh: Journals and Notebooks 1964-1980

Susan Sontag, ed. by David Rieff. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012.

As Consciousness is Harnessed to Flesh: Journals and Notebooks 1964-1980 is the second volume in the three-part series that comprises Susan Sontag’s journals and notebooks, and follows Reborn, published in 2008 to apprehensive reviews. David Rieff, who edited the series, writes in the foreword that if Reborn can be seen as his mother’s bildungsroman, the equivalent of her youthful literary hero Thomas Mann’s Buddenbooks, then As Consciousness might in turn be seen as “the novel of vigorous, successful adulthood.” The book, of course, is not a novel, but a notebook — a collection of ideas and diaristic episodes, possibly written with the future goal of an autobiography or large autobiographical novel in mind. As a result, this second volume, saddled with a rather cumbersome title (one of Sontag’s notes in the margins of 1965) and weighing in at a hefty 500+ pages, is unlikely to be read cover to cover with much enthusiasm by anyone not already a Sontag aficionado. The book is notational and elliptical at best, brimming with vague pronouncements (“The only acceptable life is a failure”); unanswered questions (“The autobiography of a guru? How do I feel about sublimation?”); fragmentary ideas; borrowed quotations; to-read and have-read lists; and enigmatic, often poetic, monads (“A spy in the house of life”).

That said, As Consciousness does manage to reveal an adult Sontag very much consistent with the budding adolescent intellectual we met in Reborn — self-critical, categorical in her tastes and opinions, deeply anguished, and always, always at work. The very nature of these journal entries attests to the constancy of her mind and her efforts, although she is self-aware enough to realize that the psychological underpinnings of this ambition may be undesirable. “I valued,” she writes, “professional competence + force, think (since age four?) that that was, at least, more attainable than being lovable ‘just as a person.’” The quotes around “just as a person,” not to mention the “just,” are telling, implying not only an unfamiliarity with, or suspicion of, the concept of being loved merely for who one is, but perhaps also a twinge of disdain for the notion of not being proficient enough in a particular métier to be loved for a reason.

Perhaps at the urging of her therapist Diana Kemeny, Sontag spends a good deal of this notebook examining the roots of such feelings in her childhood, finding her mother — an alcoholic who, she believed, equated her daughter’s happiness with disloyalty — in part to blame. Later, Sontag writes that the familial roles in her childhood were perversely inverted, as often happens in the homes of alcoholics.

This inherited dysfunction, not surprisingly, manifests itself in Sontag’s later relationships as feelings of subjugation, as well as sexual inadequacy. At the opening of the book, her tumultuous relationship with the Cuban playwright Maria Irene Fornes, whom she calls “I” or Irene, appears to be ending. Sontag is devastated — penning strange, flatline statements such as “There are people in the world” and alluding to Irene’s icy stonewalling: “There is no responsiveness, no forgiveness in her…Even a grunt of assent ‘violates’ her.’” And what seems even harsher about this rejection is that Sontag blames at least some of it on her deficiencies as a lover. “Self-respect,” she writes (her italics), “It would make me lovable. And it’s the secret of good sex.”

By 1970, however, she seems to regain some happiness and stability or “mastery,” as she calls it, with C (Carlotta), calling her “the first big intellectual event (this past week) since my trip to Hanoi.” Despite this self-professed mastery, however, Sontag’s vulnerability in love is still in full force. Indeed, gone in these entries is any trace of the self-assured critic; in her stead is a desperately insecure schoolgirl, chastening herself before a mirror: “I must be strong, permissive, unreproachful, capable of joy (independently of her), able to take care of my own needs (but playing down my ability, or wish, to take care of hers).” So much calculation and performance! And yet these feelings of insufficiency do not seem to cloud her joy. Instead she writes that at last she is no longer “busy dying” but “busy being born” — a bright, if not fraught, echo of her exhilarated teenage discovery of lesbianism in the first volume of notebooks, in which she famously declared she was reborn and then inexplicably married Philip Rieff.