Voina, Palace Revolution, 2010. Via Buenos Aires Street Art

“Revolutions in Public Practice,” a two-day conference held by New York-based Creative Time in 2009, brought together the usual suspects in today’s art world — published academics, in-house activists and well-known artists. While the conference was touted as concerned with “the work of international cultural producers whose practice engages the public sphere on questions of social justice”, in reality it wasn’t very different from any of the other myriad discussions about political art practices that have come into vogue recently. Hosted by the institutions, funded by the institutions, these “discursive platforms” provide cozy and safe places to talk about methods of making a political impact.

Last December Voina (War), comprised of five young Muscovites, made news by flipping police cars, at night, in the center of St. Petersburg, some of which still had officers inside. Not long after the raid, Oleg Vorotnikov (aka “Thief”) and Leonid Nikolayev (aka “Lyonay the F*cknut) were seized by police, transported to St. Petersburg, and tossed into a pre-trial detention facility. They have been charged with criminal mischief motivated by “national hostility”; their conviction possibly landing them in prison for up to five years. Banksy approved of their intervention, donating a tidy sum to their defense (late in February a judge ordered them released on bail). Though often very close to politics in practice, members of Voina prefer to think of themselves as artists on the road to a new artistic language.

Voina, Dick captured by KGB, 2010. Via Groundswell

Russia has a proud tradition of agitation by handfuls of dissidents. Whether anarchist or communist, secret or public, these groups have often exerted as much force on the national consciousness as on any actual levers of power. Voina locates itself firmly within the anarchist strand of this history: “Anarchism is the only cohesive, honest and fearless power” Voina’s members said in the interview for Don’t Panic.

Founded in 2007 by handful of philosophy students at Lomonosov Moscow State University, the youthful cadre — they average mid-twenties in age — often use the symbols of pirates, recently projecting the skull-and-bones onto the former Russian parliament building. Their “Jolly Roger” laser projection was some 164 feet high, covering most of the front of the White House in Moscow, now the the seat of Russia’s Premier, Putin. Unlike the organized, structured forms of protest in the West, Voina’s Jackass-style actions embrace unruliness and disorder, one of the few forms of protest available in Russia’s increasingly unstable political situation.

In December 2010 the oligarch Khodorkovsky‘s run-in with the Kremlin — covered extensively in the Western press — led to a 14-year prison sentence. Meanwhile, over 800 people were arrested in central Moscow for protesting rising nationalism, which had led to attacks against guest workers in many major cities in Russia. These assaults were carried out by members of the post-Perestroika generation, born in the 1980s, whose own aspirations are running up against the limits of Russia’s neo-liberal nepotism, which offers little to those who are not members of the de-facto aristocracy of the Kremlin-connected. In 2008 Voina performed a mock hanging of two gay and three illegal workers inside a department store. The action was called the In memory of the Decembrists — A Present to Yuri Luzhkov and was intended as a direct attack against Moscow’s Mayor Luzhkov, whose policies are frequently denounced as racist and homophobic. One recalls the suspended human mannequins used by Mauricio Cattelan, even if Voina engaged real people. Leonid Nikolayev explained: “Today the innovative art-language is the only instrument to understand the xenophobic nonsense and chaos which is around us.” In framing the work, Voina was quite clear about their satirical intentions, yet when spontaneity is the watchword, both in radical protests and in the street, slippage can occur.

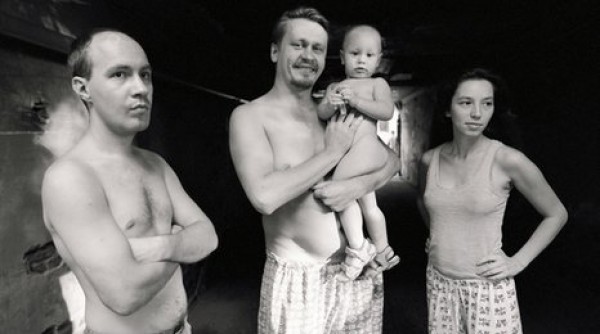

Voina members Leonid Nikolayev and Oleg Vorotnikov via BBC

There is a long tradition of political art in Russia taking place outside of institutions. With the Zeitgeist of perestroika in the 1990s, progressive artists swapped clandestine studios for protests in the streets. In 1993 the conceptual artist Anatoly Osmolovsky climbed onto the gigantic statue of the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky. In 1995 the provocateur Alexander Brener challenged Boris Yeltsin to a boxing match in Red Square. The art collective Radek built a barricade celebrating the 40th anniversary of May 1968, successfully blocking one of the major streets in Moscow. In the new century, with the tightening of Putin’s regime, political work changed tactics from pointed opposition to varieties of ridicule. The burlesque hints and tropes pushed by Voina rely on spectacle and shock. With Fuck for the heir — Medved`s little Bear! they staged an artistic portrait of 2008, pre-election Russia. This consisted of young people having group sex. The group stated in an interview that in Russia everyone metaphorically fucks everyone else

As in the West, there are Russian artists who prefer intellectual combat over risking their freedom zigzagging genitals in public. These operate on a high budget, and their work is often very professional and sleek. Antipodean to Voina, What is to be done? (Chto Delat?) started in 2003 with street actions and rallies confronting a resurgent capitalism. Recently however, the group has produced video work pursuing a kind of Brechtian mannerism. Curator Ekaterina Degot, recently describing the Russian art scene in ArtForum, noted that “everything is attuned to skillful production and visual coherence.” In contrast, Voina’s purposive vulgarity: “We struggle against glamor and conformism. In our action How to Snatch a Chicken? The Tale of How One Cunt Fed the Whole Group, a female activist stuffed a chicken into her vagina. We use the aesthetic of ugliness, absurd, and even nonsense.”

Voina, Fuck for the heir – Medved`s little Bear! via Don't Panic

It will be interesting to see if Voina acquires the new skills of “visual coherence” which Degot describes as now being part of the Moscow scene. Will Voina be invited to Biennales and asked to speak in the name of anti-professional, radical art? Their manifestos are unclear, mixing nationalist sentiment with more bombastic language. Alexei Plutser-Sarno, Voina’s chief ideologue, restricted the use of images early on. Counting anyone who has participated in any of their actions, Voina currently boasts 200 members, but the core is still six people planning in secret.

If there is an alternative to the relative violence of Voina, perhaps it is Tania Bruguera’s Party of Migrant People (PMP); an international institution with political aspirations could be considered as a new kind of radical practice. Creative Time’s audience had to be woken by a racket of a live instrumentalists — a flautist, a trumpeter, or a double-bassist. In Voina, no boredom beyond the bitter contradiction of authoritarian parody.

]]>

R.E.P (Revolutionary Experimental Space), installation view, via White Box

It is perhaps difficult for Americans to appreciate the extent to which national identity is contested throughout the rest of the world. Having maintained one form of government for so long, whose formation coincided with the birth of the nation itself, America has forever been concerned with what it means to be an American, rather than the validity of the identity as such. Consider the term ‘African-American,’ which was adopted in opposition to the more historically militant descriptor ‘black,’ which was in turn opposed to ‘negro,’ for obvious reasons. Without delving too deeply into history, it is possible to appreciate the unique status of the modifier ‘-American,’ not only here, but in other formations: German-American, Jewish-American, even Gay-American. In each case, the addition of the American identity is considered a positive, progressive step; something all the more remarkable given America’s history of intolerance. That the descendants of minority groups aspire to an identity whose history is little more than their oppression speaks to the peculiar appeal of American national belonging. The idea of America somehow contains both an institutional history of exploitation and the struggle against it.

In Europe, however, the situation is much different. While France has existed coherently almost since the the first century, for example, Italy and Germany weren’t unified as nation-states until 1861 and 1871, respectively, and only then amidst multiple claims for the primacy of other, counter-identities, religious, political, and ethnic. Socialism, in particular, as an inter-nationalist class-based identity, has played a central role in the constitution of European nationalism, not least as the common enemy of both German and Italian Fascism. But this same internationalism, when enforced on Eastern Europe by Moscow, reinvigorated the nation as a liberating concept – precisely as America’s capitalist international provoked national liberation movements throughout the third world. Thus what links, in 1956, the outbreak of the Hungarian revolution to Fidel Castro’s landing in Cuba, for all the ostensible opposition of free market theology and dialectical materialism, is this idea of national self-determination. If I dwell on it excessively here, it is only to emphasize the relative novelty of the nation outside of the American imaginary. For it is, to my mind, impossible to appreciate Minimal Differences, the exhibition that closed last month at White Box, without understanding the stakes, as it were, of Eastern European identity. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, this question of what it is to be European has only become more complicated, particularly for Poles, Czechs, Slovaks and those others who have suffered at the hands of both western nationalism and the eastern international. Minimal Differences elegantly considers how these problems have fueled social debates and become a field of artistic inquiry.

In 2004, when the European Union was formed, the disparities between Poland, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Slovenia, Slovakia and other countries became critical. Differences of nationality, ethnicity, religion, language, politics, and economics, formerly homogenized beneath the iron curtain, reemerged as these countries sought to join the nascent Union.

Anna Molska, Tanagram 2006-2007. Via White Box.

Such complex relationships became an endless source of investigation, as artists presented an array of differences filtered through their own, critical perception. Paweł Althamer, Azorro, Vesna Bukovec, Jirí Cernický, Oskar Dawicki, Katarzyna Kozyra, Zbigniew Libera, Joanna Malinowska and Christian Tomaszewski, Anna Molska, R.E.P., Slaven Tolj, Marek Wasilewski, Julita Wójcik, Martin Zet are each from countries of the former Soviet Bloc, but now partake in an ostensibly capitalist economy. Minimal Differences offers a retrospective, of sorts, examining personal versions of late 1990s history, taken with an edge of humor. In mocking the contradictions and peculiarities inflicted on them by the past, these artists display a kind of solidarity as cultural workers, as their common identity as artists is wielded against the inconsistent multiplicity of history.

Pawel Althamer, Slaven Tolj, R.E.P group and Zbignev Libera comment on the differences that originated within the political opposition between East and West. In Teledysk (Videoclip) Pawel Althamer from Poland gives us a history lesson, staging the antipathy between the younger generation and the older Poles who witnessed their country’s transition to a market economy. The differences are reflected in a set of care-free attitudes towards the past, flavored with a cynicism towards the future.

The Ukrainian group R.E.P (Revolutionary Experimental Space) presented a wall mounted vinyl cut-out formed by two shaking hands that appear as the wings of an eagle. This hand-shake takes its model from the Ukrainian coat of arms, satirizing both the history of socialist iconography and the shady handshake deals that are the hallmark of Ukraine’s new class of political oligarchs.

The exhibition also introduces artists who live outside of Europe and present a slightly different set of reflections. Johanna Malinovwska and Christian Tomaszewski are emerging artists who address issues of dress codes and representations of the future. In the series of photographs In Mother Earth Sister Moon the artists scramble references to the Soviet space program with sci-fi films and the peculiarities of Soviet dress.

Katarzyna Kozyra, The Midget Gallery buys artworks, 2007. Via White Box

The young Polish artist, Anna Molska, who was included in the Younger Than Jesus exhibition last year, revisits the legacy of modernism. In her video Tanagram two men are trying to assemble large pieces of a puzzle into distinctive shapes. The suprematist grammar of the constructions, the Chinese origin of the puzzle, the Russian song playing in the background, and the incomprehensible dialogue taken from a Polish-Russian phrase book offer a vivid portrait of the overdetermined legacy of abstract art, claimed by many nations but owned by none.

Katarzyna Kozyra’s video The Midget Gallery buys artworks offers a sort of rebuke to the international market. Her protagonists, a group of dwarfs from Poland, buffoon the de-facto regulation of the art market by certain players. Personally, I find Kozyra’s engagement of little people ethically problematic: the metaphor between art market’s spectacle and the those stereotyped as freaks seems a bit clumsy. The artist over-extends her power by utilizing demeaning clichés.

Previously I wrote about paintings by Dmitry Gutov an artist who marked historical difference by painting quotes from Karl Marx in a way that almost created a brand out of Marx’s name. Similarly Slaven Tolj from Slovenia plays on the similarities between gestures of a salute. The artist endlessly performs different variations of a greeting that was used both in parades across the Soviet Bloc and also in Nazi Germany. Tolj’s video documentation of his performance Patriot suggests that recognition and display of dominance maintains a certain consistency across contexts.

Slaven Tolj, Patriot, 2007. Via White Box

The title Minimal Differences is a pun. Socialism, the common historical denominator for each of these considerations, vigorously suppressed difference and identity. Once the state-system collapsed, however, many of these ghostly demarcations re-emerged, sometimes with a vengeance, as in the former Yugoslavia. But to their credit, these artists also make fun of the peculiarities, and the way in which differences were instrumentalized by propaganda and perpetuated by ideology. The exhibition’s co-curator Denise Carvalho has said that “ the exhibition shows a kind of irony on the issue of difference. So, the idea of difference or sameness is in the show something to be looked at as absurd.” Monika Szewczyk, the other co-curator, has said that she purposefully attempted to highlight the question of artistic representation and what it means for past histories.

By mixing more established and emerging artists Minimal Differences revives the twentieth anniversary of the Fall of Berlin Wall from two years ago. It is one of many curatorial efforts to survey art’s ongoing fascination with identity. In America, this exhibition presents a rare view of many of the strongest artists currently arriving from Eastern Europe. Being Eastern European certainly means to carry the marks of many differences, and those these might be minimal, they are often crucial.

]]>

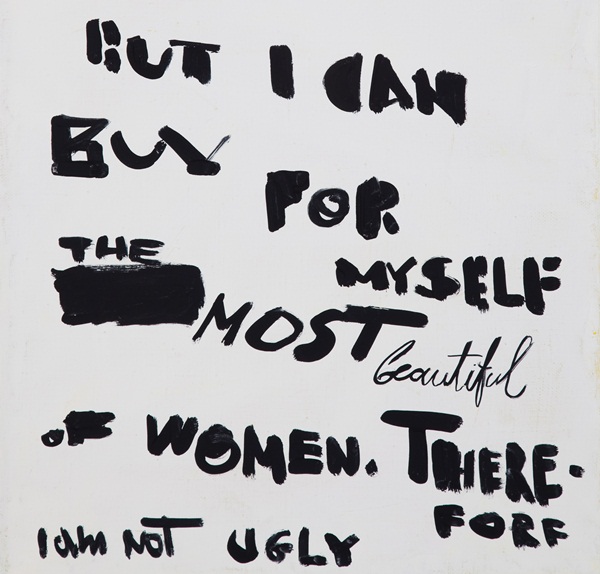

Dmitry Gutov, I am Ugly, but I Can Buy for Myself the Most Beautiful of Women. Therefore I am Not Ugly (detail) 2010. Via Scaramouche NY

At the opening at Scaramouche, a gallery on the Lower East Side, visitors drank wine and murmured appreciation for canvases emblazoned with words calling people to revolution. The work came from Russia: it was leading Moscow conceptualist Dmitry Gutov’s solo debut in New York, where he offered attractive renderings of various phrases once thundered by Karl Marx.

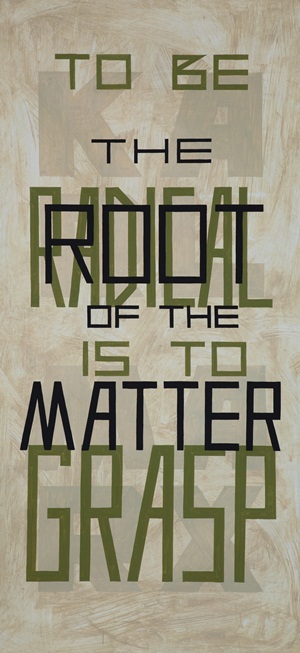

Dmitry Gutov, To be Radical is to Grasp the Root of the Matter, 2010 via Scaramouche NY

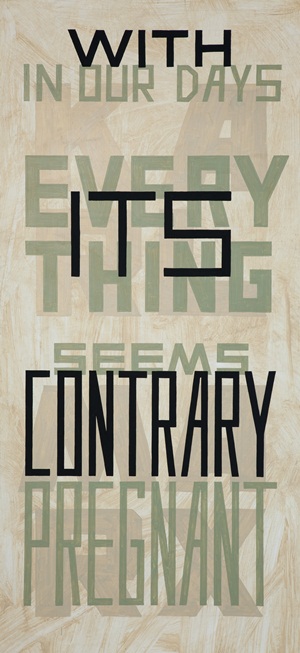

For his own part, Gutov has not allowed the collapse of the Eastern Bloc to dent his enthusiasm for the old ideas, having long been an active member of the Karl Marx School of the English Language in St. Petersburg. This group aims to purify Marx’s thinking, distilling still-revolutionary concepts from decades of officially sanctioned misinterpretations. Upon beginning his work with the school, Gutov started to hand-write Marx’s statements on canvas and cast them into metal sculptures. The very title of this show, In Our Days, Everything Seems Pregnant with its Contrary is from a speech given by Marx at the founding of the People’s Paper, and testifies to the high esteem in which Gutov continues to hold the philosopher. There is a distinct tension, however, between the sheer attractiveness of Gutov’s work and the seriousness with which he would have us approach the ideas represented therein. Though the perceived antagonism between left politics and pretty surfaces is perhaps less a theoretical position than a religious hangover – a kind of lingering, Judeo-Christian suspicion of appearance – this does not make it any less present or powerful. And what is America–the Soviet Union’s great capitalist nemesis and victor of the Cold War–to make of Gutov’s intentions?

The painted word has informed Gutov’s works for the last two decades. Previously the artist has copied lyrics of Pushkin, Shakespeare, and a controversial Russian revolutionist Mikhail Lifshitz. Similar to Robert Barry but on more painterly scale, Gutov either doodles (included in the show are smaller works written by free-hand) or neatly prints the phrases.

Dmitry Gutov, In Our Days Everything Seems Pregnant with its Contrary, 2010. Via Scaramouche NY

Here, Gutov highlights the words in the middle of a phrase in large bold, black font. The rest of the quote, cast in a lighter hue, recedes into the background. Often key words are barely readable, inscribing into the work the historical process of collective memory that has filtered these quotes along their jouney to the modern viewer. The visual play of light and dark, push and pull creates an inverted perspective, transforming the surface of the canvas into a site packed with contested meaning. The titles become a sort of key against which we juxtapose the artist’s reorganization of the words, and the distance between the two arrangements becomes significant. In one work To be Radical is to Grasp the Root of the Matter, Marx’s words pile on top of each other, with “root” pressing in on “matter.” In order to get the order ‘correct’ we have to pay close attention to the colors and layers, but by this point we are already interpreting, already rethinking Marx’s words in reference to their context. Almost without our realizing it, Gutov has us rehearsing precisely the philological relation to Marx’ work that was eclipsed by Soviet dogmatism. Looking even deeper, we see the elegant, capitalized name of Karl Marx, laid out as a sort of logo for the thinker. At the literally deepest level of the work, Gutov veers dangerously close to branding. What is he pursuing here? Is Gutov claiming that any reanimated Marxism must negotiate the reality of the world system – in which marketing, branding, and image play paramount roles? Or is he cynically commenting about his own presence within the gallery, drawing attention to its neutering effect on radical ideas?

Perhaps the artist is simply lamenting the lost legacy of Marx, as not even a contemporary crisis of capitalism seems capable of resurrecting him. Today, while exhibiting in major international venues, Gutov is part of revolving gallery world. This world may not be interested in the failure of the past, but clearly remains happy to endorse its branded reclamation. ]]>

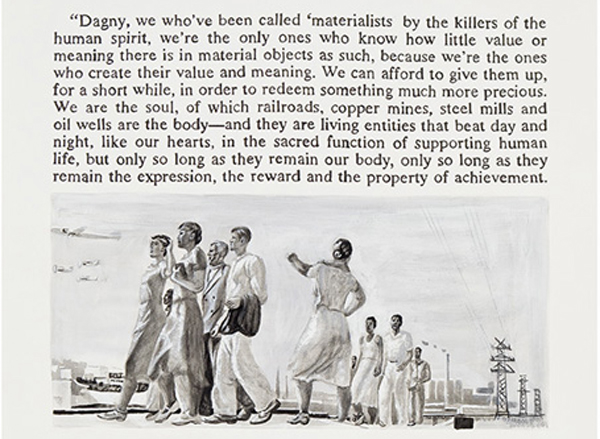

Yevgeniy Fiks, Ayn Rand in Illustrations, Atlas Shrugged page 519, 2010. Courtesy the artist and Winkleman.

A long history of complex interactions between image and text has given rise to a set of expectations about their juxtaposition. Placed side by side, we expect important connections to be revealed, flowing in both directions, as text implicates image and vice versa. In his exhibition Ayn Rand in Illustrations at the Winkleman gallery, Yevgeniy Fiks‘ doesn’t quite achieve the depth we might hope for, though he and Rand’s shared status as émigrés from the USSR does add another layer of intrigue.

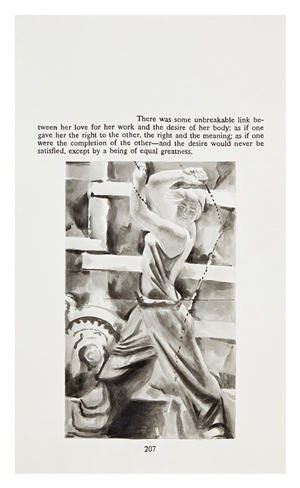

This is a very attractive exhibition, comprised of twenty-two works on paper held neatly in black frames. Each sheet of paper carries an image combining a drawing and a text. The image is dominant, consuming most of the page, whereas the texts are alternately short and long. Not all of the images are centered but float in relation to the edges of the paper. Rendered in watercolor, ink and pencil, each of these graphic studies is numbered according to the pages of Atlas Shrugged where the quotes originate. This ‘bookish’ format is sometimes convincing but it does reveal several arbitrary and simplistic combinations of text and image.

Yevgeniy Fiks Ayn Rand in Illustrations, Atlas Shrugged, page 207, 2010. Courtesy the artist and Winkleman

Overall, the texts are libertarian hymns praising industrialization and money. Included are phrases like “We are the soul, of which railroads, copper mines, and oil wells are the body “ or “ …he had no touch of that what people called culture. But he knew railroads. ” These texts are illustrated either by scenes of monumental construction or accompanied by tall, muscular people walking across newly developed landscapes. Fiks combines a quote about “some barefoot bum in some pesthole in Central Asia” with an image of a girl walking through a desolated rural area and clenching books in her hands. Her head scarf frames high cheek bones and almond-shaped eyes. Although these images are likely to be unknown to the Western viewer, the formal congruence between capitalist and Soviet ideologies has been widely studied, and Fiks flirts with simply offering a series propaganda diagrams.

There are several works that raise questions: a portrait of handsome man, open faced with styled hair accompanied by a phrase: “I want to make money.” A bronze sculpture by a Russian officer followed by a description: “He traced in space the sign of the dollar.” We are reminded of Rand’s peculiarly unapologetic promotion of capitalism. There is little humility, irony or (self-) critique when she write on behalf of book’s protagonist John Galt: “I don’t care about helping anyone, all I care about is making money.” Openly stated under normal circumstances this feels uneasy, if sort of comical; at present it sounds positively disturbing. Fiks challenges the viewer to see the extent to which our own ideological precepts mirror those of a previous, more classically repressive regime. Referring to contemporary Russian society, the artist has said that “they think that new money will buy a new happiness.” Thus Fiks uses Rand’s text to gesture towards the Russian nouveau riche, linking the new ideology with the old.

In Ayn Rand in Illustrations the question remains open as to whether Fiks sanctions these ideas in a post-Soviet, post-‘common’ and definitely newly individualist consciousness; or whether his images show the dark and oppressive underside of Rand’s brand of individualism. What’s more, by prioritizing the aesthetic appearance of the work, Fiks risks creating just another series of consumer objects, undermining the conceptual labor of his project. In this last respect, though, there does emerge a meaningful contrast between the relative humility of the commodities on display and the caterwauling self-importance of both the Stalinist imagery and Rand’s ludicrous prose. Neither, it would seem, are the stylistic order of the day (the triumph of Rand’s ideology notwithstanding) and, in highlighting their parallel legacies, Fiks does well by his larger project. Still, its hard not to feel that some of the larger conceptual stakes go unappreciated and unexplored.

]]>