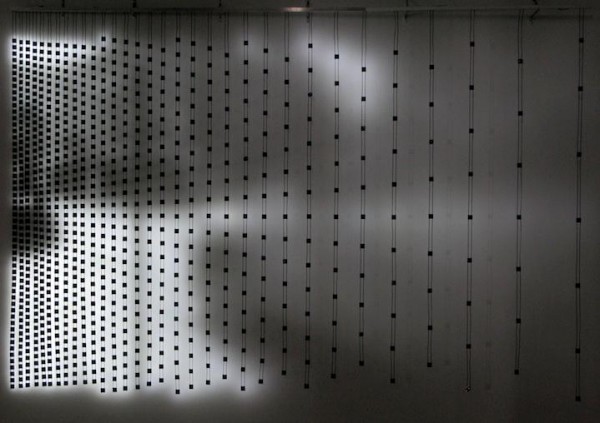

Jim Campbell, Taxi Ride to Sarah's Studio, 2010. Via Hosfelt

There are no errant cords or switches in Jim Campbell’s four works at Hosfelt Gallery. The artist’s pieces, which rely on LED technology, are tightly installed, his degrees in mathematics and engineering from MIT showing only in the precision of his construction. The total effect is poetic and surreal.

Though strung flat against a wall, the geometric spreads of tiny LED bulbs in Taxi Ride to Sarah’s Studio light up and change to represent a pulsing abstract image. Campbell has his viewers walk a line between perceiving this image and merely experiencing it moving in front of them. Elsewhere, in another work, the changing, flickering lights repeat, only now the artist has put them in motion on a three-dimensional scale. Even if one’s eyes have just barely adjusted to the nearly-dark gallery, it’s imperative to find a way through the wall of mesh netting, into a room filled by a tilted plane of evenly spaced, suspended light bulbs. With their innards replaced by gentle LEDs, the room still feels dim despite hundreds of bulbs. Depending on your height and where you choose to stand, the piece gives either the feeling of being high up and just under a pitched, starry sky, or grounded in an alternate, blinking universe.

Outside this room, a small, illuminated red box, wall mounted as a bas-relief, displays a cloudy image that scuds along just under its surface. This too seems like an image blown out to the point of abstraction, and again, one experiences its lazy movement while trying to understand what it might be. Nearby, an old-fashioned slide show clicks loudly through alternating images of scratchy family photos and their nearly whited-out counterparts. When these flash on and stay on they look, for an instant, like nothing. But a closer look reveals white-on-white ghosts of the images that follow. This, along with the red box, are as two-dimensional as it gets in this particular Campbell show, his ninth with Hosfelt.

Jim Campbell, Scattered Light, 2010. Via My Remote Radio

Though the artist has often worked in the form of flat grids – represented here by Taxi Ride – Campbell recently delved into three-dimensional territory by “pulling apart” two-dimensional work. And this is lucky for us. Campbell’s show is as much an experience, quiet and dark and all-encompassing, as it is a sight to see.

The four works at Hosfelt unintentionally coincide with Scattered Light, which occupies Madison Square Park through the end of this month. As far as an indoor show is concerned, this particular gallery is about as perfect as can be for Campbell’s museum-scale pieces. Hosfelt’s wide-planked dark wood floors and rustic beamed ceilings are a surprisingly appropriate backdrop for the Campbell’s almost bucolic take on technology. The exhibit – as it is correctly called – is truly beautiful.

]]>

Stephen G. Rhodes, Inkantinent Mochte Gemacht; Arizona, 2011. Via Metro Pictures

Entering the successive set of rooms holding Stephen G. Rhodes’ new show at Metro Pictures, a viewer might get the impression he’s walking through Grandpa’s garage, cleaned up, albeit resentfully, after fifty-some years. In a way, one is peeking in on the mess of an idiosyncratic old man – Rhodes’ referent for his work here is Immanuel Kant’s relationship with his servant, Lampe. His introduces the show with an excerpt from Kant’s “The Illness of the Head” which the artist translated himself, either very directly or incredibly sloppily, depending on one’s stance on translation.

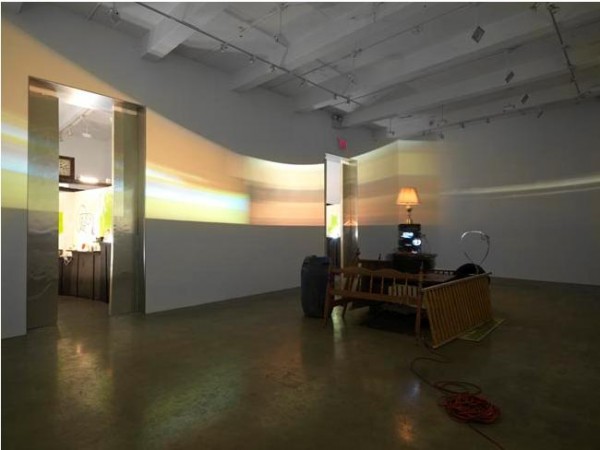

Stephen G. Rhodes, installation view, 2011. Via Metro Pictures

Rhodes points out in a footnote that Lampe woke his master daily with several cups of coffee or tea, in order to relieve “writerly and bodily” constipation. Hence the dozens of mugs, some broken, some silly – one actually says “Grandpa” on it – that line rough shelves and fill cabinets built throughout the gallery. Makeshift walls give way to semi-hidden display cases, themselves messy little satellites located in a specific, curated relationship to the whole of the show. These contain yet more mugs, along with a pointed selection of books.

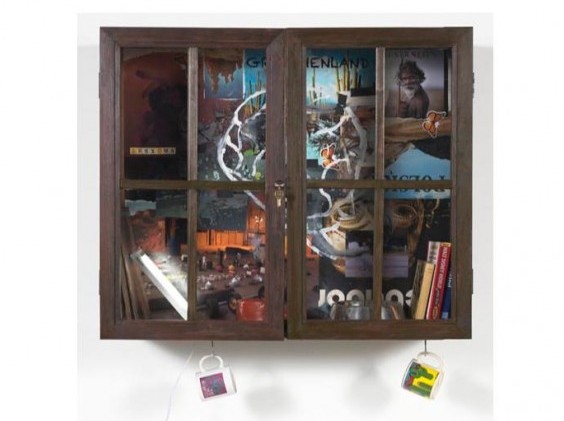

Stephen G. Rhodes, Untitled, 2010. Via Metro Pictures

In a separate footnote, Rhodes mentions that Kant was obsessed with travel and masturbation, though he never actually left Kaliningrad and resisted masturbating. The cabinets’ contents refer to these tensions. One case contains a copy of the Kama Sutra leaning against a guide to Walt Disney World leaning, in turn, against Lonely Planet: Poland. The backs of the cases are roughly decoupaged, and though it’s easy to miss the images while looking at all the mugs and assorted texts, peer closely and you’ll see a photograph of a man in the woods pulling down his pants, or magazine clippings of an Australian Aborigine. Other images in the cabinets are stills from the four films projected simultaneously in the gallery’s second room. Hopefully these are supposed to be funny, because that is what they are. Booming, drumming, and yelling make up the soundtrack to a man in a long white wig – presumably Kant – doing mundane things. A woman in an old-fashioned dress walks around outside. A truck drives past. Watching the be-wigged character sweeping or curling a flaming ball, in darkness and futility, is engrossing.

Stephen G. Rhodes, installation view, 2011. Via Metro Pictures

Suddenly the stacked quadri-projector apparatus in the center of the room spins, and all the videos rotate along the walls. This might serve as inspiration to run along with them to avoid getting caught in the light. It’s a better effect if the moving and spinning happens when the room’s bass-heavy background suddenly cuts to “Running On Empty” by Jackson Browne. Time is of the essence here, quite literally. In a separate footnote, Rhodes writes that after his first round of coffee or tea, “they say the ladies would mark the time of day when [Kant] passed.” And so the mugs adorning almost every flat space in the show are interspersed with clocks. Alarm clocks, digital clocks, clocks of all kinds. One of the last pieces before the exit is an oversized, white-faced, roman numeral clock, leaning by its lonesome against the wall. Is this a kind of coda to the rest of the installation or an invitation to the viewer to make like Kant and get punctual?

]]>