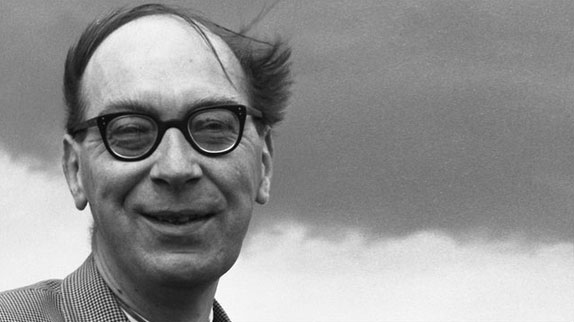

courtesy of The Paris Review

The Complete Poems of Philip Larkin

Edited by Archie Burnett

FSG. 2012.

Reviewing Anthony Thwaite’s edition of Philip Larkin’s Collected Poems, published by Faber & Faber and the Marvell Press in 1988, the great Ian Hamilton regretted the inclusion of eighty-odd uncollected and often unfinished poems. “The plumpened Larkin oeuvre does not carry a great deal of extra weight,” he wrote. In both literal and metaphorical terms I think he was right: with the exception of the indispensable “Aubade” — that soul-jolting meditation on mortality and death — there frankly isn’t much in Larkin’s leftovers I find worth the bother. Thwaite, I gather, didn’t either: my edition of the Collected Poems has been met with an editorial mop; the poems Hamilton (and many others, for that matter) found unreadable have been omitted, including the awful, jangling “Love Again,” which reads like something written by a lecherous and less-talented poet.

But here the poem is again on page 320 of Archie Burnett’s new edition of Philip Larkin’s The Complete Poems, along with hundreds of other uncollected, unfinished or (too often) unreadable poems, painstakingly extracted from letters and desk drawers and, presumably, the backs of grocery lists and lottery tickets. The editorial protocol of the book must have been something like: if Larkin wrote it, and if it vaguely resembled verse, it’s a poem. How else could you possibly explain the inclusion of:

Get Kingsley Amis to sleep with your wife,

You’ll find it will give you a bunk up in life.

Or:

High o’er the fence leaps Soldier Jim,

Housman the bugger chasing him.

One is tempted to reach for words like crime or injustice, but at the end of the day it just seems like lazy criticism. In his incorrigibly scholarly introduction, Professor Burnett assures us that “this edition includes all of Larkin’s poems whose texts are accessible,” and that “verses from letters, mainly short, and by turns sentimental, affectionate, satirical and scurrilous, are included.” And yet he claims that “mere scraps of verse” have justly been excluded. But if the following isn’t a “mere” scrap of verse, then I don’t know what is:

Oh who is this feeling my prick?

Is it Tom, is it Harry, or Dick?

The problem lies in Burnett’s motivation for this volume, which appears to have been born amid the whirr and clang of academic machinery. “An accurate text is, and always must be, the chief justification,” Burnett writes, before lobbing a handful of verbal grenades at A.T. Tolley’s Philip Larkin: Early Poems and Juvenilia (2005) which, we are told, “contains 72 errors of wording, 47 of punctuation, 8 of letter-case, 5 of word-division, 4 of font and 3 of format.” Even Thwaite’s Collected Poems does not emerge unscathed from Burnett’s introduction: its “record of sources” was often “unhelpfully rudimentary.”

Right. We’re obviously much obliged to Professor Burnett for bringing these mistakes and inconsistencies to light. We’re grateful that he has produced a text purged of inaccuracy and error. But it begs the question: how accurate is factual accuracy? What is its relation to the larger project of representing the poet accurately? Clive James once wrote that Larkin’s work “made a point of declining in advance all offers of academic assistance,” that his poetry “was, and always will remain, too self-explanatory to require much commentary.” The Complete Poems takes the opposite view. Here, Larkin is eagerly footnoted, indexed and appendiced; thirty pages of introduction, notes to the introduction, and notes on abbreviations, precede the actual poems. More than three hundred pages of exhaustive commentary documenting the formation of the poems succeed the poems. Then there are twelve pages on “Larkin’s Early Collections of His Poems,” followed by a redundant “Dates of Composition” — before the “Index of Titles and First Lines,” like the end credits of a very long and boring movie. The four collections of poetry Larkin published in his lifetime take up 97 pages. The Complete Poems of Philip Larkin clocks in at 729.

In all fairness, the commentary does occasionally manage to warrant a little interest. In the entry for “Aubade,” for instance, there’s a wonderful excerpt from a 1977 letter to Kingsley Amis, a few months before Larkin completed the poem: “Poetry, that rare bird, has flown out the window and now sings on some alien shore. In other words I just drink these days…I wake at four and lie worrying till seven. Loneliness Death. Law suits. Talent gone. Law suits. Loneliness. Talent Gone. Death. I really am not happy these days.” These sentiments poignantly made it into the text of the poem — his last, and possibly most enduring, convulsion of talent before he gradually dried up:

I work all day, and get half-drunk at night.

Waking at four to soundless dark, I stare.

In time curtain-edges will grow light.

Till then I see what’s always there:

Unresting death, a whole day nearer now,

Making all thought impossible but how

And where and when I shall myself die.

Arid interrogation: yet the dread

Of dying, and being dead,

Flashes afresh to hold and horrify +

The only problem is that the excerpt from the letter to Amis is buried in five and a half pages of notes and commentary — for just the one poem. Ultimately it doesn’t dramatically change our view of “Aubade,” it merely provides a little extra biographical padding here and there. Apart from that, Burnett’s insistence on documenting the development of the individual poem (a-ha! this line appeared slightly altered in this letter, and so on) is, well, unhelpful. The “poem” “Walt Whitman,” which, in its entirety, goes “Walt Whitman / Was certainly no titman / Leaves of Grass / …,” gets the following entry:

10 Apr. 1978, when it was included in a p.c. to KA (Huntington MS, AMS 353-393). L writes the text as four lines separated by slant lines, and leaves the fourth line as an ellipsis. He signs off as ‘young bum. ǀ Philip’. Previously unpublished.

From early on, readers have detected homoerotic feelings in Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (various edns. From 1855 onwards). 2 titman: a fancier of women’s breasts (slang); not in OED.

That “previously unpublished” bit is pretty good — as though those pathetic, left-handed lines were ever seriously meant for publication.

Does Professor Burnett imagine that the inclusion of “Walt Whitman” — or the many other bumbling snippets of nonsense like it — strengthens Larkin’s oeuvre? If so he is seriously mistaken. The only thing we’re reminded of is what a shit Larkin was in real life. There are little jibes at Donald Davie, Tariq Ali and Frank Kermode; infantile lines about feces and cunts; the odd homophobic taunt. Because so many of these poems appeared in private letters, the effect of reading them is to conflate Larkin’s art with his life — a fallacy his real poetry doesn’t deserve. It will be necessary, one fears, to rehash Martin Amis’s excellent New Yorker essay on the Larkin backlash that followed the publication of the Selected Letters in 1992. “None of this matters,” Amis wrote, “because only the poems matter.”

It’s annoying to have to drone on like this about things that seem so obvious. The Complete Poems ought to do what its title seems to promise: give us the four collections of poetry Larkin published in his lifetime, followed by the uncollected poems that appeared in magazines and anthologies and elsewhere. Instead, Burnett has given us a verbose and inaccessible tome — a heap of the half-formed and half-felt. Which is about as far from Larkin’s example as you’re likely to get: he relied on powers of economy and accessibility for effect. His gift was to combine a condensed and deeply poetic language (with its tremors of Auden, Hardy and Eliot) with ordinary speech, as in the devastating final stanzas of “Mr Bleaney” —

But if he stood and watched the frigid wind

Tousling the clouds, lay on the fusty bed

Telling himself that this was home, and grinned,

And shivered, without shaking off the dreadThat how we live measures our own nature,

And at his age having no more to show

Than one hired box should make him pretty sure

He warranted no better, I don’t know +

— whose last three words deliver so powerful and unsettling a blow and pull that long sentence to a crashing halt. “Mr Bleaney,” like “Aubade,” “Church Going,” “Next, Please,” “The Old Fools,” “For Sidney Bechet,” “Dockery and Son,” “An Arundel Tomb” and countless others, are poems wrenched from personal experience yet heightened by art into universal experience. Their endless quotability are a testament to their paradoxical generosity — the expansive reach that thwarts their brevity. Larkin’s life was by all accounts uneventful and drab, a kind of non-life, but it enabled him his many searing insights about life, age, death, disappointment and the passing of time. As he put it in his Paris Review interview a few years before his death: “I suppose everyone tries to ignore the passing of time: some people by doing a lot, being in California one year and Japan the next; or there’s my way — making every day and every year the same. Probably neither works.”

Most of us, I imagine, like to think of ourselves as belonging squarely in that first category. We might not be in California one year and Japan the next, but we’re certainly struggling to do a lot, to keep abreast of the passing of time. Yet Larkin’s way is always there with us, whether we like it or not, intensified at those moments when “we are caught without / People or drink.” It’s the voice of the unhappy — the disappointed, the ugly, the unloved — reminding us of what at certain moments we can only bear to intuit:

]]>Life is first boredom, then fear.

Whether or not we use it, it goes,

And leaves what something hidden from us chose,

And age, and then the only end of age +

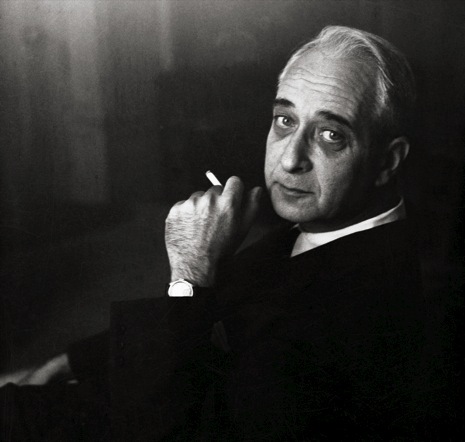

Lionel Trilling, photograph by Sylvia Salmi. via The New Yorker.

Why Trilling Matters

by Adam Kirsch

Yale University Press, 2011

Lionel Trilling is a critic to judge critics by. In 1950, when many on the far left were still writing travel brochures for Stalinist Russia, and the American political climate gave way to Senator McCarthy’s anti-Communist witch-hunts, Lionel Trilling published The Liberal Imagination, a collection of essays and reviews emphasizing “variousness and possibility…complexity and difficulty.” It was a muffled cri de coeur; muffled not by a lack of conviction, but by an aversion to slogans, pugnacity, and party politics. “These are not political essays,” Trilling wrote in the book’s preface, “they are essays in literary criticism”—yet they ascribed to literary criticism a profound moral purview that combined political, social, and cultural concerns. His essays were conceived at the “dark and bloody crossroads where literature and politics meet,” as he put it in “Reality in America.” Literature for Trilling was an art form with unique insights into the immense complexities of our lives, and he wanted those difficult insights to determine the way we think about society, politics, and culture.

This is roughly what he meant by liberalism: it is, or ought to be, an acknowledgment of complexity and difficulty and an awareness of the objections that can be raised against it. Trilling took no consolation from the fact that conservative ideas of his own time barely amounted to more than “irritable mental gestures”; he warned that “it is not conducive to the real strength of liberalism that it occupy the intellectual field alone,” citing John Stuart Mill’s admiration of the conservative Coleridge as a kind of ideal. “The intellectual pressure which an opponent like Coleridge could exert,” he wrote, “would force liberals to examine their position for its weaknesses and complacencies.” Without that kind of pressure liberalism is in risk of becoming too self-congratulatory, and thus complacent. “Emotions and ideas are that sparks that fly when the mind meets difficulties.”

Obvious parallels can be drawn to the current political climate in America, in which a floundering democratic left urgently needs the pressure of worthy opponents to rekindle some of that intellectual fire. This is part of the reach and scope of The Liberal Imagination; much more than just a “cold war book” (the first thing Louis Menand has to say of it in his introduction to the 2008 reissue), or an attack on Stalinism (as Trilling later in life acknowledged it to be), it is a book that demonstrates the moral value of the dialectical method. It considers both the yes and the no of its own argument, and encourages us to do the same.

Over the years much has been said and written of Trilling, some of it sensible and some of it outright nonsensical. As with Orwell, there has been some bickering among the left and the right as to where Trilling belongs on the political spectrum. This squabbling actually went on during his own lifetime; the writer and urbanist Richard Sennett accused Trilling of having no position and for being always “in between.” Trilling replied that it was the only honest place to be.

That said, Trilling remained a dominant figure of the democratic, anti-communist left popularized by the “New York Intellectuals”: Irving Howe, Dwight MacDonald, William Barrett, C. Wright Mills, Mary McCarthy, Philip Rahv, Hannah Arendt, Alfred Kazin, and many others—including Diana Trilling, Lionel’s wife. He may have influenced the likes of Irving Kristol and Hilton Kramer (so did Trotsky), but nothing in the pages of The New Criterion and Commentary today recalls either the fairness of Trilling’s arguments or the nuanced integrity of his method. The critic George Scialabba — contra the neocons and those on the left who derided his critique of their utopian ideals — more accurately places Trilling in a tradition of progressive liberalism: “[Trilling] was a friend of equality, of progress, of reform, of democratic collective action—a wistful, anxious, intelligent friend. He was, that is, a good — actually, the very best kind of — liberal.”

The poet and critic Adam Kirsch refers (by my count) just once to the issue of Trilling’s alleged neoconservative legacy in Why Trilling Matters, his new book—and the latest—in Yale’s ‘Why X Matters’ series. Kirsch sees a connection with Irving Kristol in Trilling’s regret, in an essay on Kipling (included in The Liberal Imagination), that the author of Just So Stories never made it clear to liberals “what the difficulties of not merely government but governing really are”: “It is not so far from this empiricist skepticism,” Kirsch argues, “to the impulse that led some New York intellectuals, in the 1960s, to critique the welfare state in Irving Kristol’s magazine The Public Interest. At such moments, the intellectual genealogy that connects Trilling with neo-conservatism becomes visible.”

Well, not to me. By Trilling’s own admission his politics were “complicated” — much to the chagrin of Partisan Review compatriots like Delmore Schwartz, who saw in the critic’s caution and multifariousness a kind bourgeois complacency. William Barrett tells the story of Schwartz’s animosity toward Trilling in The Truants: Adventures among the Intellectuals, still among the best narrative accounts of the New York Intellectuals. Schwartz was apparently alarmed by Trilling’s essay “Manners, Morals, and the Novel”, an essay read at Kenyon College in 1947 and published the following year in the Kenyon Review. It’s ironic that Schwartz’s should pick this particular essay to rail against; it contains what is (to my mind, anyway) one of the most powerful affirmations of Trilling’s belief in progressive liberalism:

It is probable that at this time we are about to make great changes in our social system. The world is ripe for such changes and if they are not made in the direction of greater social liberality, the direction forward, they will almost of necessity be made in the direction backward, of a terrible social niggardliness. We all know which of those directions we want. But it is not enough to want it, not even enough to work for it — we must want it and work for it with intelligence. Which means that we must be aware of the dangers which lie in our most generous wishes. Some paradox of our natures leads us, when once we have made our fellow men the objects of our enlightened interest, to go on to make them the objects of our pity, then of our wisdom, ultimately of our coercion. It is to prevent this corruption, the most ironic and tragic that man knows, that we stand in need of the moral realism which is the product of the free play of the moral imagination.

This is one of the best paragraphs of its kind — if there even are any others like it. It’s an intelligent, sensitive, and above all humane defense of literature, democracy, and progressivism. Born in 1905, Trilling had seen the crimes committed in the name of reactionary ideologies in Europe, and the revolutionary zeal of the Soviet Union collapse in on itself to produce a different, but equally deadly, reaction. Hence the moral obligation to acknowledge that even our most noble and generous wishes are neither innocent nor pure, and certainly no guarantee of progress. In short, life — with all its “complexity and difficulty” — does not permit easy solutions. “The problem with its difficulties should be admitted,” Trilling wrote, “and simplicity of solution should always be regarded as a sign of failure.”

So no, I don’t really see the neo-conservative genealogy all that clearly. If anything, Trilling’s belief in “social liberality” and the “direction forward” suggests otherwise. His models were Arnold and Mill; his political persuasions anxiously liberal. He remained aloof from the polemical mud-slinging of the 60s and 70s, having no appetite for simplification and ready opinion. This was not, from what I can glean, consonant with a conservative turn. For “despite his plea that the Conservatives had a case,” Barrett sensibly writes, “he himself remained a thoroughgoing liberal to the end: the cast of his mind was the rational, secular, and non-religious one of classical liberalism.”

Anyway, back to Kirsch. Why Trilling Matters is an odd book, its eight short chapters not so much about Trilling as they are variations on ideas or essays of his. Kirsch provides a sensible first chapter, “Does Literature Matter?”, in which he discusses the tendency among contemporary critics to assign to Trilling the “role of literature’s superego”; when writers like Cynthia Ozick lament the decay of literature’s cultural authority, it is usually Trilling who is upheld as “the emblem of those lost virtues.” Kirsch clears away the doomsday verbiage, arguing that “the current crisis of confidence in bookselling, publishing, journalism, and so on, can make it much more difficult to be a writer or a reader; but it cannot finally lead to the death of literature, because literature does not live by those things in the first place.”

Trilling himself offered one of the most cogent responses to this form of anxiety. In “The Function of the Little Magazine,” his introduction to a decade of writing in the Partisan Review, he wrote that “generally speaking, literature has always been carried on within small limits and under great difficulties.” We should not be guilty, he went on, of what Tocqueville called ‘the hypocrisy of luxury’. A good reason, then, to argue for the importance of a critic like Trilling. “The name of the activity by which readers and writers communicate,” Kirsch notes, “by which they make the private experience of reading into the common enterprise of literature—is criticism.” Trilling’s engagement with the literary culture—and his engagement of the literary culture with society at large—is a model for anyone who believes that literary discourse is an indispensable part of our public discourse.

But Why Trilling Matters fails to make this case. Maybe it’s a failure of form; one hundred and seventy pages on why Lionel Trilling matters sounds more like a really terrible exam prompt. What’s more is that twenty pages are dedicated to the issue of Trilling’s Jewishness — that is to say, the non-issue of Trilling’s Jewishness: “I cannot discover anything in my professional intellectual life which I can specifically trace back to my Jewish birth,” Trilling wrote. “I should resent it if a critic of my work were to discover in it either faults or virtues which he called Jewish.” Enter Kirsch: “Trilling approached modern literature from an explicitly Jewish perspective.” A little later on: “it is clear [that] Trilling made Jewishness the name of a way of being that is “pacific and humane,” and that stands opposed to a seemingly more attractive way that is “fierce” and “militant” … to be Jewish, for Trilling, is to stand both inside and outside the modern, to embrace its liberations and mourn its casualties.”

How so? Kirsch writes earlier on that “Trilling was too intellectually rigorous to believe that he could be nourished by the legacy of Judaism, when he knew almost nothing about it” (my italics). So he has to rely on just two essays — “Isaac Babel” and “Wordsworth and the Rabbis” — to construct his overarching theory of Trilling’s “explicitly Jewish” identity. The great critic’s failure (for that’s what it was) to engage publicly with modernist writers (not to mention Allen Ginserg’s Howl) becomes part and parcel of some vague, specifically Jewish embrace and non-embrace of the modern — according to Kirsch. The whole thing brings to mind Ilan Stavans’ absurd and reductive claim that “modern Jewish literature is a kind of clandestine universal club — so clandestine, indeed, that often its members might not be aware of their own membership.”

This is finally less of a Trilling book than it is a Kirsch book — a shame, because at its best Kirsch’s criticism sometimes approaches the Trillingesque (his book on Disraeli, and his study of midcentury American poets, are both excellent). In Why Trilling Matters, however, he tries to enlist Trilling in his own, strange battle against the legacy of modernism, quoting selectively from a select few of Trilling’s texts. The best thing that can be said for the book is that its publication may or may not convince an unfamiliar few to glance at the old master. Which they should: Trilling does matter, even though Why Trilling Matters doesn’t prove it.

]]>