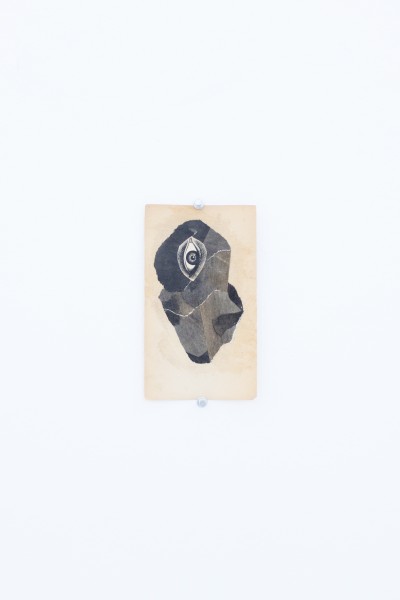

Song’s Deco Rerun, 2012. courtesy of the artist.

In Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, the titular artist told writer Pierre Cabanne:

I shy away from the word ‘creation’… on the other hand, the word ‘art’ interests me very much. If it comes from Sanskrit, as I’ve heard, it signifies ‘making.’

This is the same Duchamp to whom the quote ‘I consider painting as a means of expression, not as a goal,’ is attributed. The same Duchamp whose readymades challenged the understanding of pre-made pieces in gallery settings.

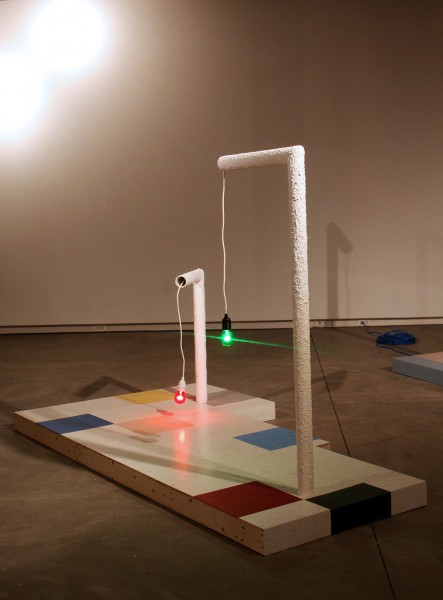

Chicago-based artist Min Song takes cues from the great, and from these quotes in particular, with her surprisingly solemn installations. Drawing from a wealth of history — of design, of architecture, of spaces both domestic and institutional — Song constructs small cross-sections of different architectural realms. We view what Song describes as ‘a struggle with site-specificity, in which I see dogmatic and ethical problems.’ For Song, ‘the transference of certain physical moments as present in a room to an object’ occurs when the object and the room are symbolically synchronized, ‘speaking similar languages.’ She references shelving, surfaces, lighting and decorative embellishments of the home, and morphs them into abstract forms that become almost painterly in their display. A dangling light bulb in a home is purely functional. Removed from its typical setting, Song seems to ask us to ponder and ultimately revere it.

Hence her work’s aforementioned solemnity: asked to view something like the triangular structure (is it a bookshelf?) of Display Function, or a portion of vinyl flooring in Marlene, as paintings, the everyday objects that serve as her media are transformed. The heart of each installation is their function as homages, commanding both inspection and appreciation. It makes sense, given her background — she was a painting major at Chicago’s Art Institute, and if painting is a classical art form, Song can make the most abstract shapes classic in presentation. A resident at the Miami-based Michael Jon Gallery, Song was featured in the gallery’s booth at the New Art Dealers Alliance (NADA) fair during Art Basel Miami Beach last year. Over e-mail, prior to the show, she explained that her construction of art objects — somehow connected to real objects in the world — ‘is a way of memorializing the things that are outside of myself, but still exist in the world in physical terms. Duchamp’s urinal — the memorialized, in this case, to me is a creepy doppelganger of the urinals that bear its likeness. That’s a good space to think about changes in functionality.’

Song’s Clementine, 2012. courtesy of the artist.

Song often expresses this literally (as in the instance of Duchamp’s urinal). Take Clementine — in which chunkily-textured PVC pipes house Christmas-color light bulbs, and dangle above vinyl-tiled cafeteria floor. The piece is easily an icon of a real-world living room. Accompanying her works are photographic or otherwise two-dimensional images, which Song explains function as ‘points of origin, where the objects find themselves metaphorically tethered to the images’: archival photographs of 1950s living rooms set the tone for Clementine and its accompanying structures. The standing lamps are so similarly posed the PVC pipe-and-bulb lamps in Song’s installation that they appear as the same objects, albeit in a more complete state.

However, it is the nature of any deliberately placed construct to evoke something other than itself, whether that is the intent of the artist or a projection of the viewer. Song is inherently complicit in this process of transmutation, displaying sculptures with the same veneration one would, again, give to painting. In a description for her show at Happy Collaborationists in Chicago, she explains: “special attention is paid to materials located in both the domestic and the institutional that mimic and suggest things other than themselves.”

At NADA, which took over the Deauville Hotel on Miami Beach and housed its booths in ballrooms, Song’s metal and chain sculptures Mediated Parallelogram and Mediated Square initially seemed to recall their materials in other settings. Here, there were no accompanying images to give the works a narrative. Instead, the two works hung directly on the wall themselves, becoming both frame and framework. “I wanted to be more direct and explicit with this body of work so explicit references became embedded in the objects themselves,” Song says, and it works.

Song’s Mediated Parallelogram and Mediated Square, 2012. image courtesy of Najva Sol.

Somber and sturdy like grave markers, the side-by-side pieces demand a kind of idolatry. The ‘mediation’ in the pieces’ titles might imply the reconciliation between the coexisting realms in which they live: the home (the hardware smacks of in-house DIY projects), sculpture, and, on a highly symbolic plane, the cemetery. Set aglow by the gallery lighting, they seem charged with a kind of otherworldly power. They are tomb-like, and it was Song’s intention, it seems, to render them reminiscent of death and its signifiers.

Mediated Square is especially dynamic: the draped chain, hanging from small screws, contains large loops, so long they nearly reach the floor. Viewed alone, it almost feels eerie — considering Song’s own deeming of Duchamp’s urinal-as-doppelganger, ‘creepy.’ But the two works, less doppelgangers of their components in the ‘real world,’ represent the melancholic, sobering, liminal space of the cemetery. Neither piece has a chain that covers the metal structure underneath it completely, as if they are revealing secrets. As Song explains, the ominous draping of the works’ chains is no accident:

One of the most common symbols one sees in the cemetery is the urn with a drape that never completely covers it. It’s a classical symbol of death attributed to the Romans that, through the partially-covering drape, symbolizes the spirit’s escape…the drape of the chain in either wall work borrows the gesture.

Song’s Neo Geo Candle Swindle, 2012. courtesy of the artist.

While design might be Song’s most keen and obvious interest, a new context emerges when Mediated Square and Mediated Parallelogram are considered: perhaps the messages contained in her works are more subversive or thematically exploratory than they appear. In Untitled (Log and Two Boxes), the log seems to both burst from and divide the plastic boxes, suggesting an intervention of real, breathing life in the midst of stoic display. Her Neo Geo Candle Swindle — a chunky red candelabra — is a nod to Deco design, but once the actual candles are burned, it becomes an eerie centerpiece, evocative of something’s end. Mediated Square and Mediated Parallelogram are not Song’s first forays into the subjects of life, death, and movement through the stillest of exhibitions. Of these two pieces, Song says:

They do cull physical and symbolic references from cemeteries and death. I associate candles, light with the finite in my work: the candles burn out, the light bulbs die. Despite the finite life span of life as represented in the two media, they can conversely talk about eternity. So it’s a way to consider mortality.

Mediated Parallelogram and Mediated Square feel strangely revealing. The pieces sit side-by-side in contrast: the dark heaviness of Square; the powdery beige frame and delicate chain of Parallelogram. As they become indicative of tombstones — and a spirit’s escape — they transform into something beautiful and unsettling. To be fair, there’s an already established quality to any piece in this sort of setting, even a readymade — consider Duchamp — and especially at NADA. But Song’s work contains meaning, inherently, in its very parts and unexpected movement– such as that of a burning candle or a seemingly innocuous chain. This might be another aspect of Duchamp’s take on ‘making’: Song’s ability to construct portraits of life, death, and the passage of time through placid, architectonic structures. Her painting background makes this kind of one-off portraiture possible, but so too does the broad definition of art as making. Even within the object’s own bounds, what one might construct of it spiritually and meaningfully is limitless.

]]>

viewers gather at an opening. courtesy of Ferro Strouse Gallery, Brooklyn.

Artists Maximiliano Ferro and Allen W. Strouse have last names that lend themselves well to a business. “Ferro Strouse Gallery” sounds and feels like a lot of rich, moneyed things, but, like so many cultural venues in the outer boroughs, it’s nothing more than the owners’ apartment. When Max, an artist and Cooper Union graduate, needed a place to live, Allen, a writer and current Ph.D. student in English at the CUNY Graduate Center, allowed him to sleep on the floor of his Harlem apartment. Ferro never left. Eventually, the duo transported to a one-bedroom off the Broadway-Junction stop in Bushwick and opened a gallery.

If Brooklyn apartments-as-galleries offer an alternative to the traditional, sterile gallery setting, Max and Allen’s space is, in turn, an alternative to any other apartment you’ve seen utilized for this purpose. The walls are wood-paneled and there’s enough flannel and soft material to give it the feel of a basement slumber party. There’s an unaffected purity to this setup: a lack of “gallery-feel” adjustments to the apartment is precisely why the viewing experience is so effective. One gets the sense that the displayed work is viewable for art’s sake, that it needs neither platforms nor explanations. It’s inviting, even warm.

Last October, Ferro Strouse’s first show, End Vehicles: Sketches for Later Works, was a testament both to the purity of art’s existence in a welcoming setting and Ferro Strouse’s own mission. The accompanying curatorial text stated:

The sketch is a statement of faith — faith in the artist’s vision, faith in the process of art-making, and the ability to side-step time. Mediating between the realized and the latent, the sketch encourages a posture of hope in the future. In its dedication, the sketch marks out a space for love.

This could easily be a description of the bravery that comes with churning out a labor of love from your own home. Max explains:

The show was a nice parallel to the beginning of the gallery. It’s still in its sketch form. When you see a sketch, even if you don’t see the resulting sculpture, you see the idea for it. And in a way, it’s already there. It already exists in your faith that reality and time and space exist. Starting this gallery is an act of faith.

The approach is almost spiritual at its core, less about art itself and more about belief and reality and the connectedness to oneself and to the community. Ferro Strouse is not a good blueprint for galleries of the future if the end goal is stability, and less idealistic experimentation. Transcend those for a moment, though, and it all makes sense. So much culture comes through D.I.Y. venues — music, art, news — and, beyond looking and feeling better than its mainstream counterparts, they’re vital and necessary. Ferro Strouse aren’t so much riding that wave as they are excitedly, prettily surfing it. In this way, with these ideologies, the space could exist anywhere, even in a typical gallery.

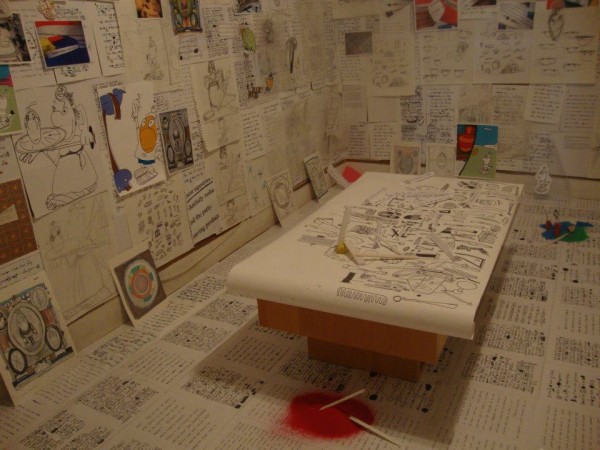

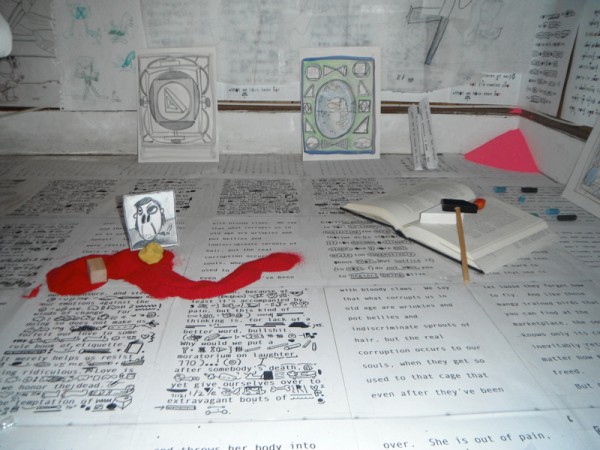

At the time of this article, the artist on view at Ferro Strouse is Katie Merz, a Brooklyn-born visual artist and former professor at Cooper Union, which is where she met Max. (Of their meeting, she says, “Max was a student of mine seven years ago. He absolutely stood out from day one; he was from another, beautiful place. His imagination was a planet.”) Merz’s latest project, pieces of which are on display at the space, is a MacDowell Colony-granted collaboration with writer John D’Agata. He translated the writings of Plutarch, she translated his words into accompanying cartoons. Merz was the perfect fit for the first solo show at Ferro Strouse, given her opinion on the gallery industry: “I don’t like galleries, not big business ones,” she wrote in an e-mail,

It makes art very status quo and makes artists a bit desperate to be included in a made-up hierarchy. Ferro Strouse is free-spirited — a do-it-yourself or ‘build it and they will come’ attitude. Why wait? For what? To be included by whom? Artists are engineers of their own fate.

installation shot of Merz’s ‘The Unpleasable One / The Beginning of Language.’ courtesy of Ferro Strouse Gallery, Brooklyn.

Max and Allen are engineers of the fate of every visitor, too, and their consequential experience and understanding of the displayed works. At the opening for both Merz’s show and End Vehicles, there was no wine — only cake. Ferro Strouse has its own manifesto, including the credo:

Wine at openings is stupid. We will have cake, ice cream, pizza, and chips. Because what you really want is to have a Birthday Party for your little kid self.

This is cute and tasty, but it’s also entirely strategic. “There is a theory to the birthday party,” says Allen:

I would really like to avoid the pretension and tediousness of the wine and cheese at the opening. It’s just really boring and everyone hardens themselves with liquor and avoids real emotional involvement. It’s just fake, tedious conversation. And I think what people really want is the joy of childhood and openness. When we did that at the first opening, it was so great! It was really obvious people were having a good time.

slice of opening cake. courtesy of Ferro Strouse Gallery.

It seems counter-intuitive to remove nature’s social lubricant for a good time — drinking at a gallery feels like a natural way to become less self-conscious. But, counters Max, “I think we don’t really need wine at the opening. People think alcohol loosens them up. But I think it robs them of that exciting awkwardness that happens when you’re approaching someone you don’t know. You think you can just do whatever you want when you’re drunk, but you miss the step where you have to say, ‘Oh, this is going to be a fun adventure,’ because you just jump into it. You don’t get to press START before the game. It removes the necessary acknowledgment that it might get weird.”

That’s why the first bullet point on their manifesto is: “It’s okay to be scared — we are, too.” Explains Allen, “It’s less like a birthday party and more like the junior high party before everyone starts illegally drinking, and it’s more awkward.” Is art minus a shield so scary, though? Max and Allen think so, primarily because they feel art is massive, important, and intended to make the viewer bemused, inquisitive, or even emotional. The manifesto goes on to say, “We aren’t afraid to speak of Truth and Beauty,” and — right below that — “We are sick and tired of art that’s ‘so bad that it’s good.’ We believe in making things that are actually good.” The next bullet point: “Does that make us naïve? Yes, but we read our post-modern theory. And we’re not going to be somebody else’s leftovers.” This is where the manifesto begins to read less like a list and more like a thesis. They seem to acknowledge that purposeful art is, as they described, “naïve,” but necessary.

When I ask what it means to believe in art that is actually good, Max explains:

It connects to the first line of our manifesto: ‘It’s okay to be scared.’ I think a lot of artists take this distanced stance through multiple lenses when they make their work. You can’t really see the author. That’s exciting if you’re trying to explore ambiguous authorship, but I think people often do it because they don’t feel comfortable in their worldview. They then mask that with an attitude of sarcasm or irony. They feel that nothing is worth anything, because anything can be criticized. But you don’t have to be afraid of being criticized.

When art is ironic, or mocking itself, the conversation “ends there,” Max continues. “You’re putting yourself above it, like you already understand it. And we don’t understand anything.”

Allen agrees:

I don’t know why people who make art, and people who make galleries and museums, don’t want to actually make art. It seems like for whatever reason, believing in art is really unpopular. Every piece of art is ‘art because it’s not actually art.’ And I always feel insulted by that, because I really care about art. Art is special and important and you can actually believe in it, even if that’s weird or unpopular. It goes back to creating those junior high moments, those awkward situations. We don’t care if it’s awkward, because art is worth looking kind of goofy for.

Ferro Strouse, then, is an attempt to right the wrongs of irony, complacency and sarcasm present in the commercial art world. It’s arguable, though, that art is guilty of those traits because people are guilty of them, too. In this way, Max and Allen aren’t just unique artists or unique curators, their specific understanding of the world is a complete contrast to the mass from which they’re attempting to distinguish themselves. Max feels that it’s important not to reduce any of Ferro Strouse’s ideas to statements about what is or what isn’t art, and to take note of the fact that our contemporary situation isn’t so contemporary. Max says:

When Allen says that people don’t believe in art, [remember] that people just don’t want to believe in anything. Or they do, but they think it’s not appropriate. It’s not appropriate because everything is on thin ice right now, but everything has always been like that. People just think it’s different now. They think it’s not worth believing in anything because they’re going to be let down. That’s so sad.

If that’s the problem, turning one’s apartment into a showcase of art that believes in itself is only one solution. It seems that Max and Allen — gallery or not — embody, holistically, beliefs in oneself, the world, and, ultimately, in genuine sharing. “We have this really strong faith that it’s possible to make art and that art really matters,” Allen explains, “I really think that it’s necessary, and that it’s the only thing that makes life worth living — in a broad sense.” According to Ferro Strouse, art and life ought to be intertwined in a way that’s sincere — one cannot verily live without the other.

“I think that everybody is creative, but not everybody is a creator,” says Max,

Creativity is not going to the art store. The way you start a conversation, the way you step onto the train, the way you place your pillow as you turn, half-asleep, at night. The way you write an essay or cook food or make an image. I guess you could even be accidentally creative, but as long as you feel that you’re utilizing your mind and spirit to make something, then I think you’re being creative. I think our ability to do whatever we want is a divine gift. Right now, I’m saying things that will become ideas in your mind. That’s no joke. I take that seriously.

detail of Merz’s current show. courtesy of Ferro Strouse Gallery, Brooklyn.

Merz, whose work is on view at Ferro Strouse until next month, shares this idea, this concept that the belief in art is the belief in living, and vice versa. “Art is the life force, the chi of culture,” she says. “We think we can survive without integrity, beauty, and spirituality, but it is not possible. It is necessary, because it feeds our spirit, and our body and spirit is all we have. Art is a force; we don’t realize how powerful and necessary it is, but it keeps us humane.” Merz’s own drawings vary between hyper-kinetic, childlike cartoons and soft, abstract, pastel lines — a duality derived directly from her childhood and that Max and Allen both found appealing. In her practice, as Merz’s accompanying statement explains, “no hierarchies are implied. Lines, and respect for the changing integrity of line, is what the practice is.” Merz elaborates, “A line, a breath — you follow it and it can go in any which way. But you play along. You follow it.” That’s it: Art is breathing. Art is how you move.

Katie Merz: The Unpleasable One/The Beginning of Language is on view at Ferro Strouse Gallery until December 6, 2012, at 77 Pilling Street #2, Brooklyn.

]]>

Philip Greenberg for The New York Times.

Much has been said about the hybrid role of Lower East Side legend Clayton Patterson: archivist, activist, artist. A former president of the Tattoo Society of New York — back when the act was illegal in New York State — the Alberta, Canada-born photographer, filmmaker, and painter has amassed over thirty years’ worth of video recordings and photographs documenting the Lower East Side of the 80s. Patterson photographed the neighborhood’s characters and ephemera almost obsessively, snapping gang members, cops, mystics, addicts, and anarchists in front of his apartment door. Eventually, Patterson’s practice took on a political slant: often working in tandem with his now-wife, Elsa Rensaa, the two filmed illegal evictions, the Tompkins Square Park Police Riot — the video of which landed Patterson in prison — and, eventually, the horrors of 9/11, effectively capturing on film what was arguably the end of an era.

The multiple layers contained in Patterson and Rensaa’s archives are rich, dense, too complex to enumerate, though they include the stories of characters like Lionel Ziprin, L.A. II — Keith Haring’s little-known collaborator — Bad Brains, street gang Satan Sinner Nomads, and drag queen Peter Kwaloff. They’re messy archives, too, neatly arranged but constantly growing and dissolving concurrently. A shot of the archives in a 2008 documentary about Patterson, Captured, is overwhelming: stacks upon stacks. Patterson has made a career of championing the underdog — he infamously quoted on Oprah that “Little Brother is watching Big Brother” — and documenting a substantial chunk of under appreciated but significant history. But: what to do with all of it?

With the help of willing volunteers and organizations — among them Steven Stories Press — Patterson has been turning his archives into books, the first of which was Captured: A Film and Video History of the Lower East Side. The latest,Jews: A People’s History of the Lower East Side, was recently funded by Kickstarter and is still in production. OHWOW published and distributed Front Door Book in 2009. I met with Patterson and Rensaa at their home — which doubles as the Clayton Patterson Gallery and Outlaw Art Museum — to discuss their history, the archives and their future.

Monica Uszerowicz: You’re an activist, but you’re also a visual artist. Can you tell me about your artistic background?

Clayton Patterson: I’ve always been an outsider artist. I started getting things going in Soho after I came to New York in 1979. I really didn’t like that yuppified world. It was heavy on gossip. What’s interesting is that Richard Brown Baker collected some of my stuff, and after he died, it was given to Yale. I’m now helping Jeremiah Newton with his collection of work by Candy Darling. Candy Darling, aside from being part of Warhol’s world, is also this kind of icon in the transgender world. There’s this collector, Laura Bailey, who is transgender, and she had this huge collection of gender and transgender material that got purchased by Yale, so we’re trying to get part of Candy Darling’s collection to Yale, taking into account that she, too, was transgender.

The thing about Yale is that it has three active archivists working on this transgender collection. That’s really important with archives. If you give an archive to a place and they don’t have money to deal with it, it can sit in boxes forever. But anyway: there’s a crossover if it goes to Yale, because it turns out Laura Bailey collected my book, Captured, because of some of the Lower East Side characters documented in it. That means it’s connected to Richard Brown Baker, and these links start getting made. Links are truly important.

MU: And your work is really all about links, in a way. Links between people.

CP: Exactly. Back to the art: I continued working outside of the mainstream, and then in 1985, I opened the Clayton Gallery and Outlaw Art Museum. I showed mostly outsider art. The ‘outlaw’ factor pertains not only to criminality, though that is included. My time as a so-called outlaw plays a role, too. The police considered a lot of my documentation a criminal law; I went to court for well over twenty years for documenting on the street, such as the Tompkins Square Park Police Riot video, which I made in August 1988 with the assistance of Elsa Rensaa. I was arrested after some of the portions of the tape were put on the news. This was the first time a hand-held, commercially available video camera was ever used in a case like this. Eventually several cops were fired.

It’s said that history is really created and made by the victors. And in a way, it’s true. Artists must document everything they do in order to stabilize it. The chance of you being recognized for your contribution can be lost. You need to clarify your own work. Even now, I might be considered a legend in certain arenas, but that’s not part of the larger arena. If you go to Harvard and ask who I am, nobody will know. But if you’re hanging out at Max Fish, someone will say, “Oh yeah, that guy’s a legend!” That doesn’t really translate in a historical way.

MU: Your archives hold a lot of stories. You’ve gained a very broad, encompassing understanding of that world.

CP: That’s true, but I never focused on the upper echelon. My interest was always in the outsiders, the low end. The focus is inner city people. On the cover of the Front Door Book, which I published with OHWOW, there is a picture of a security guard. He is no longer alive. I know his son, and that’s really one of the only pictures of his father that exists. There are a lot of pictures like that in the archives — pictures of kids who were in gangs, too. But these images aren’t really important on a larger, social scale.

MU: But you still feel what you’ve documented is significant, right?

CP: Of course. I understand that the real genius comes from the roots and up. So many people accomplished things while riding on the backs of others. I always tell people, if you really want to be famous, you have to groom and develop one idea. Eventually, the idea will expand and other people will understand it and it will become palatable. RuPaul is a good example of this. I started shooting photos at the Pyramid Club because of my friend Peter Kwaloff, who is now known as Sun PK. The Pyramid Club really contributed to the 1980s East Village drag scene. That’s where Nelson Sullivan — the person who turned me onto the video camera — filmed RuPaul and Peter in their early days. Peter had a different drag character every week at the Pyramid Club shows, which made it very complicated for people to catch onto him. RuPaul, on the other hand, was just one, accessible character. Nelson let all these people stay at his place: Lahoma, Larry Tee, RuPaul. Nelson made the introductions, made it all possible. Nelson introduced me to the video camera, so I have to respect that. RuPaul doesn’t write about him in his book, but Nelson changed a lot of people’s lives.

And you know, so much genius came from cheap rent, from the ability of people to just move here and live capably. Those roots are now being cut off. New York is so gentrified that it has eliminated the gene pool. Genius is the fresh ideas, the outside ideas, the ones that change how we see and think. A lot of it came from the poor, the impoverished, the inner city.

MU: And so much of it is in the archives.

CP: One of the reasons I make these books, the anthologies, is that you need a hard copy of this. When you get on the Internet, you skim. You do searches. With a book like Captured, I included people who I felt were really critical to the whole situation, but were maybe unknown or obscure. Different people have different opinions about why something happened. You want to give everyone a voice. In the end, you’ll never know who was really right. In Resistance: A Radical and Social History of the Lower East Side, we featured an excerpt from a book by Ron Casanova, who was homeless and living in Tompkins Square Park during the police riot. He mentions that the police made a deal with the homeless population regarding a portion of the park in which they could legally stay. So the story about the police giving the park a curfew, thus closing it to everyone there, was an outrage. That’s what the riot was about.

MU: When you read history, it’s usually filtered through one voice, one idea. And that’s what the history becomes. Maybe you’re trying to prevent that.

CP: Right. I’m finishing up Jews: A People’s History of the Lower East Side, and I included a history of Lionel Ziprin, who was a major voice of his time period. He never became to famous — he wanted to remain obscure — but he will exist in the book. People who look in the book for Allen Ginsberg will eventually be led to Lionel. They’ll find Lionel and then a new door is open, new ideas flow. When you look back at art history, all those people you read about — Cézanne, van Gogh, DuChamp — the reality is that, yes, they were outside thinkers who were way ahead of their time, but many of them came from rich families. They were saved. Their work was saved. Other people who have made equal contributions, who were maybe influential to van Gogh — you’ll never know about them, because they will never exist.

MU: It’s overwhelming to think of all the incredibly creative people who were missed by history. But there are certainly famous artists who weren’t rich. Do you think luck plays a role in helping people become famous?

CP: I think a lot of it is attached to money and power and being within the system — or who you know. A lot of the ideas that percolate from the bottom take a long time to be understood. That’s why I say, if you develop an idea now, the masses have to understand it. But the masses aren’t the ones who change history. It’s the people who have a different understanding of things that change history — and that takes years to get to a wider public. That’s why it’s important to have those voices saved: if you don’t preserve it, it won’t exist. And that’s why I started doing these books. Hopefully, roots will grow out of this.

MU: When did you realize you were building this archives? When you first started documenting the neighborhood, did you know you wanted to specifically “store” these people, or was it just for artistic purposes at the time?

Elsa Rensaa: They asked Edmund Hillary why he climbed Mount Everest, and he said, “Because it’s there.” That’s what Clayton does. Because it’s there.

In a way. This is a very interesting question. It wasn’t really a plan or strategy. It developed naturally. I captured the last of the free and the wild and the crazy Lower East Side. It’ll never be that again. It was such a mix. And the great thing about immigrant populations, like you had in the Lower East Side, is that you get everyone from the idiot to the genius, because they’re all contained in that one package. A lot of it flourished — this great wealth of people that changed the history of New York.

MU: So you captured some of the last moments of the neighborhood containing a mix of different kinds of people.

CP: Now it’s homogenized. It’s about money, status. After the ’87 stock market crash, which didn’t affect real estate, rent kept going up. Now you have competition like NYU, which a corporation buying up billions of dollars worth of real estate. Then you have all of these real estate investments in companies. You have luxury hotels. These are solid bases that will forever change the structure and the economy of the neighborhood. America had a short period of time during which you could experience this Horatio Alger idea — pulling yourself up by the bootstraps. The possibility of coming up from the bottom and working your way up has been eliminated. Coming here from western Canada was like seeing the United Nations. Each culture that came from through the Lower East Side left something behind. You could experience a small part of their culture, and it was all very affordable.

MU: But how do you feel about places in the outer boroughs — neighborhoods that are ethnically diverse, cheaper than Manhattan, where a lot of artists are creating spaces for themselves?

CP: Well, the rent is cheap in those places for New York. But you still have to be working all the time to make that rent. And you don’t have that same cluster, that same density, of different kinds of people clinging together.

MU: Do you think that vibe can happen anywhere now, though?

CP: Well, I think the muse has left New York. People talk about New Orleans or Detroit as possibilities. I think China is a good example of a place where repression is happening, where it’s difficult, but the artists coming out of there — even the tattoo artists — are high-profile, really incredible. In the film, Captured, there’s a photograph of me leaving court during the trial for the Tompkins Square Park Police Riot tapes; it says “DUMP KOCH” on my hands. Ai Weiwei took that photograph.

Something else I documented was the transitional period the police experienced at that time. You didn’t just see artistic creativity there. In this instance, the creativity belonged to the cops. In the Riot tapes, one particular shot is interesting: the white shirt is waving for the blue shirts to stop, and they don’t listen. That meant the chain of command no longer existed. That’s what made it a police riot. In 1988, the police couldn’t control a ten-and-a-half-acre park in the Lower East Side. By 1992, the police were a razor-sharp, military organization that could control the streets anywhere.

Those cops spent four solid years down here re-organizing. This was the perfect petri dish for that. You had the anarchists, squatters, the drugs. They had lots of chances to practice down here, because they experienced real resistance from the locals. That resistance helped them to reorganize.

MU: Let me go back to the building of the archives. There is a struggle with it, regarding both its size and future purpose. Can you say more about this?

CP: Getting it recognized is hard. People are not really interested in this history. The people who were the geniuses, who bubbled up to the top, left the neighborhood and never looked back. By the time you get to their grandkids, who started coming back in the 1980s, or other people from that era — people like Blondie, John Zorn — they grow up and develop, too, and don’t necessarily think of themselves as part of the neighborhood’s history. They’re part of the history of punk, of rock. You kind of lose that connection to the roots of the neighborhood. And nobody has any real interest in the archives—nobody who could substantially do something with them.

MU: What are some other struggles?

CP: Economically, it’s a struggle. Trying to preserve the material is a struggle — a lot of it is dissolving and breaking down. Organizing everything is difficult, too. The lack of outside interest is hard. Making the books is hard. By the time the archives really get appreciated or loved or understood, a lot of it could be broken down. Also, Elsa and I are getting older, so it’s not something we’ll be able to manage or take care of.

MU: When you turn parts of the archives into books, they become utilitarian, educational tools. Why are the books important?

CP: It condenses the information and preserves the history. It creates layers. I think it’s one of the only ways to save the history down here, because it was so complex. History changes, memories change, and there’s no crust that holds the whole pie together. The books, hopefully, are that crust. Though I would like the book-making process to become easier. I have the ability to gather the information, but somebody in this world who can publish these books has to be interested. You want to be known and valued for what the archives really represent. So much of the roots of America came out of the Lower East Side.

ER: Years ago, Marshall Berman predicted what was going to happen with New York, and he was right in a lot of ways.

CP: There was always this big idea to turn the Lower East Side into what it wasn’t. You had Robert Moses, who wanted to put a big highway that cut through here into Williamsburg. Cooper Square caused that to be halted. Anyway, you don’t really have a radical community here anymore, no radical roots, so there’s no resistance to any of this.

MU: How do you feel about smaller-scale radical groups or artist communities in other neighborhoods, in New York or in other cities? I know the rent here is impossibly high, but do you feel that things like that are legitimate elsewhere?

CP: It’s not a matter of legitimacy. I think it’s a matter of passion and of connection. For example, I think a lot of people in Williamsburg aren’t really connected to the roots of the neighborhood the way people in the Lower East Side were.

MU: They’re not working with the people who’d been there.

CP: You can’t take a predominately black neighborhood and expect the new, white neighborhood to have any roots to it in the same kind of way. You don’t really have that base. There were people on the Lower East Side connected to the prior five generations. And for anything that artistic or radically significant to ever exist again, the model has to change. The model of the past was always connected to poverty and cheap rent.

MU: Yeah. It’s more expensive to do anything now, and I think people are more cynical. So — sum up for me what you’d like to see happen with these archives, besides the books. Do you want to see another Renaissance, or do you just want to make people understand the history?

CP: Of course I’d like to see another young generation develop and grow and flower out of this place, and to see people that didn’t come from wealth make a contribution to the world. My whole goal is to save the archives and put them in a place where they’re accessible to other people. I want people to be able to use them — to write, to learn. That’d be my ideal goal: something that isn’t static. I want this to be energized, to function, to be part of a community. I want it to be a wealth of material that other people can mine, get joy from, discover.

]]>

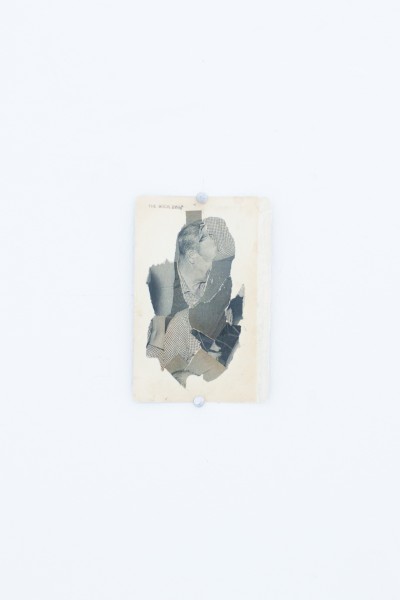

Denver-based Mario Zoots’ collages exist in a dreamlike reality: faces and shapes are reformed, their individual parts becoming cleverly hidden or exposed until they coagulate into something entirely transformative. The viewing experience can be disorienting, which in itself implicates Zoots’ belief that there is a presupposed psychology and ideology inherent in images. It is his intention, it seems, to distort that language, ultimately reappropriating it and raising questions about how — and why — it exists. Ideas regarding the Internet and the fetishism of its exigencies — and the ways in which both have reformatted typical modes of thinking — have seeped into Zoots’ recent work via digital images and manipulation. The result: the aforementioned dreamy quality of his work becomes curiously juxtaposed to its roots, which is more hyper-cerebral than whimsical.

Polymathic to the core — he is one-half of art and music collective Modern Witch — Zoots’ foray beyond small print zines and into galleries has produced works more inherently introspective than before, as the placement of his pieces in visceral print form ultimately complicates them. The accompanying description to his upcoming exhibition at Mexico City’s Preteen Gallery, ‘I JUST WANNA BE AS PRETTY AS I FEEL,’ is a collaboration with Preteen’s curator, Gerardo Contreras, and discusses the exploration of notions about hallucination and the existence of the self, appropriately manifested in Zoots’ new, psychedelic collages. We discussed over e-mail the details of both the show and his earlier work.

Monica Uszerowicz: When did you start making work? I’m hoping you can think as far back as your childhood for this, and explain your eventual transition to collage.

Mario Zoots: As a child, I used to draw mazes. My mother told me that I would sit at the table and stare at these drawings and spend a lot of time making complex tunnels on paper. I think this is something that I have carried into what I do now, being totally obsessed with repetition. The years leading up to collage were filled with studies of typography as hieroglyphs, using the spray can as scalpel.

The first collages were made in 2007, a friend of mine showed me his process and introduced me to Best-Test rubber cement. For the last six years I have been very active with my collage practice, physical and digital. In 2009 I became interested in NetArt. Around this time I stopped producing physical work; I wanted my imagery to only be viewed online. I was obsessed with immateriality. Time went by, and now I am back to making physical collage objects again.

MU: In your own words, you are “engaged in the excavation, re-imagination and manipulation of contemporary culture.” Can you discuss your personal take on the importance of media figures — and the visual depictions of them — as symbolic language for our culture?

MZ: Contemporary life is a series of images that repeat themselves again and again. My immediate surroundings inspire my work; it’s a simple formula. Have you ever been in line at a grocery store and noticed all the gossip magazines in the stands before the register? Globe, InTouch, Star Magazine. Big, bold letters: “J-LO BETRAYED!” Images of Tom Cruise and Angelina Jolie. It’s image, text, and color all working together. It’s beautifully disgusting, a complete ready-made in my opinion. I want to enlarge these magazine covers by 900% and hang them in public places.

MU: I understand you’ve taken an interest in exploring these same concepts as applied to the Internet, to the “Tumblr generation.” I feel like the cyber world has reworked our general mode of thinking. How does your appropriation and re-appropriation of contemporary culture extend to the Internet?

MZ: The Internet allows me the freedom to work at a fast pace. I like working through multiple ideas at once and going back and forth between using images found on the Internet and those in magazines and books in my studio. But even with the works I make completely analog I really enjoy viewing on a screen; the Internet browser is the perfect frame sometimes.

MU: In the description for your latest show, ‘I JUST WANNA BE AS PRETTY AS I FEEL,’ you reference Daniel Lagache’s notion of auditory hallucinations. His take on them: it is the result of an alienation of speech which gives rise to philosophical questions about the source of the voice. It’s usually the self’s own voice — its body specifically — and this touches upon the question of existence, self-awareness. You mention “the horrors of consciousness,” of memory, of being. How does your newest set of work address this kind of question of being and existence?

MZ: ‘I JUST WANNA BE AS PRETTY AS I FELL’ is a collaboration with the director of PRETEEN GALLERY, Gerardo Contreras. Gerardo has created a written piece that describes the show and he has also chosen specific collage works of mine made during 2012. In this show I am exhibiting four works on paper using source material found between 1967 and 1969. These collages are black and white and are made on the insides of 1960s science fiction book covers. For the most part, I have only shared these collages online through sites like Flickr and Instagram. People are always surprised to see how small they actually are. When viewed online you can see every detail and blemish. In real life, they feel and look different.

Together we have married language and image to create a psychotic exhibition in Mexico City. Gerardo touches on themes of psychology and hallucination in his writing via the theories of Daniel Lagache. I think his interpretation and deconstruction of the work is interesting and it works well. It made me view this collage series in a whole new way. My work is always experimental — I make images and leave it up to the viewer to complete it in however they see fit.

MU: You once said, “When I change images, I believe the psychology of the image is still intact…but then I find the disruptions and interruptions in my art to be haunting and mysterious.” I’m wondering if you can elaborate on that. In popular media and images in general, there is a deeply-embedded language and meaning and thus a particular psychology. How does your rendering them mysterious alter their meaning, if at all?

MZ: Obscuring and interrupting the embedded psychology of an image creates mystery. When viewing an object or image, I take everything I know about it from memory and try to make sense of what I am looking at. I believe the viewer can experience the same process. The interruptions in my work, most times crude, are haunting because they question motive. Why would you remove the focal point of an image? What am I supposed to be looking at? You tell me.

MU: Is one of your goals to make the viewer feel a sense of detachment from the original image, as the image itself has literally become displaced? This reminds me of the aforementioned displaced auditory hallucinations. In what ways does your alteration affect the viewer’s perception?

MZ: Detachment, uneasiness and sensations of the uncanny are the themes I work under. Living in an age of chaos, collage takes the excess scraps of post-culture and tries to make some sort of sense or confusion of it, my work being the second. Appropriation to me means creating a new world within an existing one. Each viewer takes away something different. My goal is to dissociate the familiar.

MU: One of your earlier pieces — a repeated, deconstructed image of Elizabeth Taylor — got me thinking about how the image itself was probably extracted from the Internet. You can see an “original copy” of something online, but it’s never a solid image, and this is just inherently understood. How does an image’s placement in this sort of “cyber reality” affect its presentation? How did that piece come about?

MZ: I made the piece ‘Trance End’, the day after I read about Liz Taylor’s death on the Internet. The way I found that particular image was through an image search I did on google. I searched for ‘Liz Taylor’ larger than 10mp (3648×2736). I found an intense black and white portrait of a young Liz Taylor. I made fifteen 24×36 prints of this celebrity headshot; I also made a smaller version that could circulate tumblr. There are so many copies of copies online and in the real world. The original now comes second to the multiple in contemporary society.

MU: Shifting gears a bit: you’re also a musician. Is expressing yourself or an idea via music more fulfilling in any way? In what ways does music satisfy you (in ways visual art does not)?

MZ: Performing late in the night at a stinky underground club with a crowd dancing to our music is one of my favorite things to do. I feel that my music can reach a much more diverse audience than any of my art could. I’ve created so many works things that exist online, and you have to be privileged enough to have a computer with the Internet to experience them. However, bringing people from all backgrounds together for a celebration of being alive is a real powerful feeling; it’s these experiences IRL [in real life] that I value most.

MU: Through the stylings of Modern Witch and your own visual work, I’ve become curious about your interest in the occult, in magic and spirituality. Can you tell me about this? Is it correct to assume this is a genuine interest of yours?

MZ: Modern Witch is a project that allows me to explore themes of the Occult and Ritual. It’s a fascination and longing viewed from afar. I am not a practicing occultist; it’s more of an aesthetic interest of mine. Modern Witch is techno-spiritual. We repeat technique and theme in a ritualistic way through audio recording and related artwork, all the while using Internet technology as the main vehicle for distribution of this media. A goal at the time was to make the visual elements just as important as the audio.

The word “occult” means hidden, and at the beginning of this project that is what our intentions were: to remain anonymous to a certain extent. We had a heavy online presence, but there was no information on who was making the music and art. We kept releasing music videos on Youtube and music through our Myspace page; we gained a following through this mysteriousness. Eventually that all changed.

all images are installation shots of ‘MARIO ZOOTS: I JUST WANNA BE AS PRETTY AS I FEEL’ courtesy of PRETEEN GALLERY, Mexico City

]]>

I'll Cross That Bridge When I Get to It, installation view at Fredric Snitzer Gallery, via

Bert Rodriguez is a Miami-based conceptual artist. He has worked with Fredric Snitzer Gallery for the past thirteen years. Emotional Blackmail, a group show featuring his most recent work, opens at the Saag Gallery in Alberta, Canada on September 24th. A member of the now L.A.-based OHWOW arts collective and community and a winner of a Frieze Foundation Commission, his work has also been displayed in the 2008 Whitney Biennial, in Berlin at Sassa Trülzsch and, last year, in Naples at Annarumma 404. While his works range in medium–sculpture, neons, and large-scale, sight-specific installation–their common threads are humorous and critical displays of the art market and the simple examination of the human condition’s complexities. We met with him in his studio in Wynwood to discuss the playful quality of his work, his light-hearted mockery of the art industry, and the economy of gesture.

Monica Uszerowicz: I want to discuss a statement you made in your interview with Charlie Rose. I feel it’s a good reference point. You said if what you’re making is not considered art, if it fails to register in the brain as an expected “artwork,” it’s potentially something bigger, something that can trigger an unusual reaction. The discussion of what “art really is” is very trite, and surely traditional “art” can produce various reactions, but could you speak more to this idea?

Bert Rodriguez: Sure, though I’m afraid of sounding presumptuous, or like I think I’m ‘bigger than art.’ That’s not what I mean. There’s this idea of allowing an object to elicit a response or experience that can exist within any context, whether it’s in or out of the art conversation. I began making art in the first place because I felt like an outsider. After getting introduced to art history, I thought: ‘I can do that, too.’ I began doing whatever I thought seemed like fun to do, then placing it within that [art] dialogue.

It’s become an unconscious part of my practice. All of my ideas come from outside of the art world; they’re designed to filter through that conversation and then come back to the rest of us, to the viewer. The viewer can then be part of this conversation. It’s not a political thing, because I’m not intentionally strategizing to alienate the art world or make it seem pompous. It’s a beautiful place that allows me to do whatever I want. But I want to be conscious of its qualities that exclude a certain part of the world — as if some people can’t be part of the dialogue because they’re not educated in the history. Experience is experience. In its purest form, it has a value and a meaning to anyone, and people can understand it on their own terms. That allows them to evolve, to become self-aware and more articulate — literally an evolved human being.

I like to think about art in terms of cultural or physical human evolution. As an artist, you create an experience that causes a change in the brain. I imagine synapses of the human brain firing off or building connections with other synapses. Your brain is actually changing and evolving and you’re becoming a more advanced creature. I could make some small thing, and whether it’s good or not is irrelevant. That stuff is still happening. It happens everywhere, all the time, really. It is a matter of consciously creating circumstances where you’re exponentially growing the potential for that to happen so people can walk away from the experience with the seed planted. Now it gets to grow inside of them.

MU: I remember reading that you said one of art’s most important, subtle abilities is its knack for taking human experience and condensing it into something small.

BR: Yes. To me, there are generally two different sorts of artists. One makes things that are, on one hand, based on simple ideas. But they take this simplistic gesture and make it seem more complex than it is, in order to give it meaning. They give it value with a grandiose or over-complicated surface. Once you get through that, it’s so simple. An example of this — and he’s not the best example, but he is the most famous — is Matthew Barney. I think his sculptures are a little more effective, because they’re quiet and give you time to breathe with them. But take, for example, his films: he’s built a very esoteric language and system of expression, and it’s almost impenetrable. Of course, we can take something away from this, but it’s very frustrating to be able to see that there’s a specific idea to be gleaned from that, and when you finally get to it, it isn’t so complex.

I hope I am the other artist; it’s the one I would prefer to see out in the world. This person works with complicated ideas that are a part of everyone’s life and experience — I mean, just the idea of love itself is such an intricate thing to navigate. They take these beautiful complexities we all share, then whittle them down to simple, effective objects or experiences. The condensed thing is so unobtrusive that bigger concepts can easily grow out of it. That’s beautiful to me. That’s like magic — taking multi-layered ideas and figuring out how to express them with a simple gesture. It’s the economy of gesture, which is a very important term. I think about it all the time.

MU: That’s an excellent way to encapsulate it. I want to talk to you about I’ll Cross That Bridge When I Get To It. This was the first work of yours I’d ever seen, and I was fascinated by the concept of making a piece every day. I also thought it was a wonderful comment on the art market, since the prices were set before the pieces were made. The humorous suggestions it makes about the nature of a future market seem inherent.

BR: I got that idea because, well, the kind of work that I make is labeled “conceptual,” which is a term I’m also not very comfortable with. What action or gesture isn’t based on an idea, a concept? There has been the historic criticism that conceptual artists are lazy. I typically don’t produce that much work; I focus on sight-specific installations most of the time. I don’t have a traditional studio practice in which I make a bunch of things in a room, then transfer them to a gallery. Something out there has to elicit a conversation that I continue and somehow resolve. It’s more like problem-solving or social anthropology. So I thought I’d challenge myself to not think about the work I was making.

I think my brain tends to lock ideas in there and work through them. I wanted to set up a situation in which I would not have that luxury. I would have to wake up, make something, and put it in the gallery. That was one aspect of the show: to challenge myself and make work in a completely different way, the way a traditional studio artist would. But I wanted to push it to a comedic extreme. Instead of working on one piece for a month, I had to do something every day, nonstop, like a machine. That’s where the title comes from: “I’ll cross that bridge when I get to it” describes my usual way of thinking, not worrying about things until they’re there. I had to constantly cross that bridge.

The preset prices came from my being so hyper-aware of the context of the art market. The work was in a gallery, and galleries are designed to sell art. That is their purpose within the system. It does get a little tiring for me to address that every time I do a gallery show, but I can’t help myself. The fact that the gallery wants to sell it has to be part of the work. It seems unnatural to not include every variable. That’s why I wanted to touch on the idea of the future. I was becoming more successful and gaining a much more critical reputation, so I wondered if I could sell my work, sight unseen, before it was even made — a futures market. I wanted to gauge how much that reputation is worth in some false way. I wanted to see how many of the twenty-six pieces I could sell before they were even made, to see how many people trusted in me. This is what I mean about doing something simple that can expand into larger ideas. The issue of faith is presented in this piece by its nature — having faith in a person to follow through with his promise. If you make a promise to me in the form of a check, I have to promise to give you something that is at least worth that. That’s a relationship, that constant exchange.

MU: You said you get most of your ideas from outside the art world. I think every artist does. But you speak highly of the human mind, the human experience. At the risk of posing such a large, abstract question, what are some of the experiences that inspire you?

BR: That is not the first time I’ve been asked that, and I don’t think I’ve ever answered it well.

MU: Let’s narrow it down to a specific piece, then. We can use I’ll Cross That Bridge When I Get To It. The individual works in that definitely employ the “economy of gesture.” What were some of the other, more humanist ideas you drew from? I remember a note from your girlfriend excusing you from making anything. The note itself was marketable.

BR: My girlfriend was going back to Seattle for the summer that day and I was bummed. That triggered a thought about how people constantly make up excuses to not do their job, because they’re tired, sick, or sad. I wanted to work that in, and it triggered a memory of my elementary school experience. I was a nerdy, sickly child, and often had to skip out on P.E. In those instances, a kid’s mother writes a note asking for him to be excused from the activities. That led me to ask my girlfriend to write a note for me. And that was the piece. It was a perfect stream of consciousness process, and the object itself became interesting. It elicited all these ideas about excuses, denying your role and function in society, and getting away with things, which the art world gets accused of all the time — artists being able to get away with whatever they want. So I worked in a conceptual angle that was funny but still solicited some layers, although it was a very small gesture.

A Wall I Built With My Father (Paris), via

MU: A Wall I Built With My Father and A Meal I Made With My Mother are also very straightforward pieces that suggest several elements.

BR: Right, everything I do can or can’t inspire something. My dad and I have always had a tense relationship when it comes to what I do for a living. I was going to Paris for a residency, which felt very prestigious. I was in a foreign country, doing precisely what parents would want their children to do — making money, traveling. They are signifiers of success and I was a living example of it. But my parents still don’t completely relate to what I’m doing. They’re slightly offended by it because they don’t understand it. I realized I could use that money to fly them over and figure out what to do with them. My dad is a carpenter, my mother’s a cook, and I thought I could apply the language of what they know — with me as a partner — to see if it could alter their perception of it. What they do can subtly and subtly change once it’s in a white-walled gallery, and I wanted them to see this. They’re both very interesting tasks — building a wall is traditionally associated with masculinity and cooking with femininity, politically speaking.

MU: So even politically-charged ideas were naturally ingrained in these actions and their display.

BR: They were growing from those basic gestures. There is also the metaphor of the wall representing emotional and physical distance. Building a physical wall with my father in the real world was a simultaneous act of tearing down the invisible wall between us. It was completely intuitive. That is sort of how my process goes: one small idea triggers another, and then I have this one simple thing I can do that discusses the entire process, along with other subjects I wasn’t even thinking about. This piece ended up suggesting sexual politics and cultural politics, too. My parents came from Cuba to Miami and never left. The idea was to make a better life for their children so they can live more leisurely lives. Now, I’m that person they made the sacrifice for, bringing them to a foreign country and taking care of them. I’m now the parent, using them in these pieces to give them an understanding of it all. The roles reversed via this piece.

A Meal I Made With My Mother (Paris), via

MU: Can we go back to the statement you made about not trying to express a sentiment of anti-establishment in your work? You’re certainly poking fun at that establishment — the art market — while you’re positioned within the same industry.

BR: As a kid, my dream was to be a comedian. To me, it’s the highest form of human expression that exists. It is the most vulnerable, the most fragile, the most direct. Good comedians allow everything about themselves to be scrutinized. And they’re putting all of us out there at the same time — they’re pointing out all our weaknesses, vulnerabilities. For me, it’s not about animosity; I just want it to be known that we’re all the same. It’s as if I’m on stage making fun of how stupid I am, then doing the same thing to an audience member. It’s funny and acceptable because you’re within that context. I don’t think anyone’s ever asked me this, and answering the question is what’s making me think of an answer. I think this is a pretty good one. It’s a great example. Once I’m in the art world itself, in that space, I’m able to make these statements. I’m just interested in having everyone — me, the collectors, the viewers — be completely vulnerable and exposed on every level all the time. It’s good to jab at them to get them to open up.

Regarding the humor in my work, I’ve found that laughter — which is why stand-up comedy is so sophisticated and beautiful — opens people up without them knowing. It opens them up to allow for more thoughtful meditations. When you’re done laughing and you’re exposed to all this stuff, you actually start to think. You become more considerate about the thing you were laughing about. I think I’m lucky that whatever knack I had for being funny has made its way into my work to enable that thing we discussed: the cultural, human evolution. It occurs more effectively. Wow, did that even answer the question?

MU: It did. I understand your interest in taking members of different spheres and, through humor, allowing them to connect to something larger. But do you ever wish the market was more egalitarian? Art is a luxury, which can be problematic. When the nuances of any system are put on display by an individual within it, even jokingly, one questions if there’s a way to reconcile the artist’s perception of the institution in which he works with the work he makes.

The True Artist Makes Useless Shit For Rich People To Buy, via

BR: Well, you have to ask what the problem with that is. When I see artists who are angry at the art market, it seems ego-based. It’s all just issues of control. Artists are so egomaniacal to begin with. I had to learn early on that I don’t have any control over what happens after I make something. There’s no amount of effort or action that’s going to give me control over that thing. I want to evolve in a certain way, or trigger a certain evolution, whether I know where it’s going or not. What happens once it’s out there is for everyone else to figure out. The fact that these objects are traded and commodified, that there is a monetary value for them — well, there is a value for everything. We live in a capitalist society.

On the other hand, I think it is extremely irresponsible for any artist to disregard that aspect of their practice. They must know its rules of engagement and understand it so that they are not taken advantage of. You may not have control over it, but you certainly don’t have to be a victim of it. There shouldn’t be any surprises. Yet I have nothing against it. I love the idea that I get to pay my rent by making weird, esoteric pieces. However, I’m not saying there aren’t other problems. I definitely think art schools, especially master’s programs, are not encouraging exploration and intuitive questioning and processes.

MU: What do they seem to be encouraging instead?

BR: They’re including the market in the conversation way too early. They have gallerists and curators coming through about once a month, doing studio visits with kids. But students are supposed to mess up and hammer things out. Like comedy, it takes years to refine and hone who you are. The other problem is that they’re not as encouraging of intuitive creation, like making something and discussing it afterward. Students need to know exactly why, when and where they are going to make each gesture, so that when it’s complete, it’s a soulless reference to other things. They’re trying to build really smart artists because the art world is constantly under scrutiny for its cultural value. So I think they do this unknowingly, without realizing it, in an attempt to give the work more external validation. But I don’t think anyone has to be a victim of that. The great artists are still going to come out of that system. The weakling artists who wouldn’t be making art after they finished school anyway don’t end up doing it, because they didn’t get in touch with that thing.

MU: It feels inconclusive to end this without asking you about Miami. You’ve seen it grow into a once-a-year-Mecca for Art Basel, and have stated that this negatively impacted the local art climate. I’m hoping you can discuss this further, but I’d also like to know about your general relationship to Miami and its growth. Do you feel you must represent it in a particular way?

BR: This is always difficult. I have some kind of responsibility for it, but my ideas about what that responsibility means have changed. Before, I wanted to live and die here and be the intellectual grandpa of it all. Then Basel showed up and brought us an international eye, and it’s had a lot of positive benefits. But I’ve seen it shift the creative output of this city — it’s made galleries kind of complacent. In terms of the artists, it’s affected their practice in such a way that they don’t see the value of a continued process of making work. Their practice has become market-driven — they only start to make work when Basel is coming. That is not a healthy practice. Like I said, a lot of these kids who are just leaving art school can’t be entirely blamed for doing that. But more successful artists can definitely be blamed. Plus, Basel has created the facade that there’s something happening here, and when you actually navigate and look through it, it’s not there.

I’ve realized that in order to be truly responsible to the place I love, I have to expand beyond its borders in an aggressive way. If you can become a historical relic that comes from and always returns to a particular place, then you’re building a layer of history. That’s what culture needs; it’s what this city needs, because it’s still so young. Given all the crazy things that have happened, like the Mariel Boatlift and an influx of Cubans changing the landscape, it’s experienced so many quick alterations. Nothing’s ever had a chance to ground itself and lay root. I have to gather materials from elsewhere to build upon that. The other artists that come out of here and take that approach will add layers, too. Soon there will be an actual foundation, and a real arts community can be built.

]]>