A Nightmare on Elm Street, via retroist.com

New studies in nightmare research are coming to a sad conclusion: bad dreams serve no purpose. Though scientists like Ross Levin and Tore Nielsen have postulated “fear memory extinction” as the function of nightmares, the less exciting but more persuasive arguments of G. William Domhoff of UC Santa Cruz are winning the day. In chronic sufferers, nightmares are hard to get rid of, and Domhoff compares them to headaches. He advocates “rescripting” the nightmare, and that’s a tried and true home remedy. As Freud began his work on dream interpretation in Vienna, in England, Alice in Wonderland, whose heroine “takes control” of her nightmare and ends it of her own power, was rising to popularity. Once Freud himself became prominent in America, Shirley Jackson reacted with The Haunting of Hill House, which was the basis of both Disney’s Haunted Mansion and Wes Craven’s Nightmare on Elm Street. Jackson’s wonderful misreading of Freud was that there is a kind of telepathy between people, living and dead, which, when repressed, became The Uncanny, which could manifest in the disfigurement of wallpaper into grinning faces, possession by the malevolent dead, and worse. The cure, for Freud, Lewis Carroll, and Shirley Jackson, was expanded consciousness. Awareness saved the day, or at least evened the score. (H. P. Lovecraft mutated “horror” into “weird tale” by creating a cosmos where awareness made things worse, not better.)

The 1984 classic Nightmare on Elm Street, with its sub-par acting, stupid villain, and tacked on “twist” ending, has finally been remade. Far from pandering to lovers of torture porn, the new movie rescues of the slasher genre from Hostel fans. And it’s a good film. It may, however, be good for bad reasons.

We have the sense, in this remake, that the world is a very bleak place. The young heroes’ lives don’t look like they’re really worth living. They hang out in creepy diners, bemoan their breakups, and envy the sterile “romances” of couples at neighboring booths. All they could have, if they survived, is the well-photographed but superfluous dystopia with which director Samuel Bayer encumbered his vision. That lessens the impact of the deaths. Craven’s Elm Street was a bright and cheerful place, where kids could be kids. They could swear, they could screw, and Freddy’s appearance in their dreams didn’t phase them much at first. The same was true of the film itself: like a child’s nightmare seen through adult eyes, the original Nightmare is no longer frightening. Further, the bogeyman’s pedophilia, once implicit, is now the sole criterion for Krueger’s wickedness. This was a mistake. The revelation of the story absolutely relies on his having been a child murderer. Burning a child murderer is always the right thing to do. We’re meant to understand the parents completely on that score. But in Craven’s version, we’re meant to shudder when we realize that they simply replaced their dead children by having new ones, and never spoke of it.

We have to compliment the purification of the genre. This is slasher. Things jump out and yell “boo!” a lot, and to dislike a film for that is ethnocentric: to criticize that would be to condemn the audience for liking the effect (and, oh boy, did they) which we must not do. It’s a “boo!” genre now, and slasher never ascends to become horror. In horror, we might be startled, but the method of the demise is more horrifying than the initial fright. Dario Argento perfected this, and Saw kept repeating these tragedies until they became farce. This movie eschews it. Beyond the opening, when a teenager opens his throat in a crowded diner, the demises of the protagonists aren’t very dreamlike or interesting. But the phantasmagoria of suburban weirdness is gone, too. Indispensable lines like “Freddy’s dead, because Mommy killed him” are replaced with nothing. The kids do their own detective work and discover their own histories. Craven carefully faked the stupidity of the parents, leaving them tragically in control of the kids destinies at all times. As energetic as those original heroes were, they couldn’t do much without their parents cooperation, which they never really got, even when they begged for it, screaming, from barred windows and through a haze of sedatives. In this film, the parents are just dingbats.

Also gone from the remake are the mini-essays of the original, which none of the fans seem to miss. The Balinese method of dream-control is no longer quoted. The camp stupidity of high school scenes was broken up, in 1984, with a lecture on Hamlet as a play about the futility of trying to discover the meaning of images. Like the gravediggers, says the on-screen teacher, we dig for explanations and find only grim comedy. In the original, when the line, “I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams” is uttered, the heroine has already succumbed to the nightmare, and the suspense is buoyed by another layer of existential hopelessness.

Though the first film looked cleaner, its cosmology was more fetid, a version of the quasi-mysticism of City of Glass: “This is how things are. Plenty of clues, no solutions.” (The franchise rewarded its customers with more and more revelations about Freddy’s origin, and the cosmology of withheld revelation is a commercial religion. Craven himself wanted the movie to be over once Nancy stopped believing in Freddy, and he wanted everyone brought back from the dead: it was all a dream. That ending is Alice in Wonderland‘s.)

Someone has a vested political interest in making sure nightmares never become tools of revelation: the remake’s failure to re-invent the central villain or maintain the affectedly beige personae of the parents (whose evil is the central insight of the 80s slasher genre–Jason’s mom, etc.) renders the film less eerie than simply wrong-headed. Because the fact is, the new film embraces the Catholicism of its doomed protagonist, Quentin, who, like the Pope, believes it was wrong to persecute a child molester. This is the message of this latest Nightmare, which should be recommended to all non-dissenting Catholics by their bishops: Nightmare on Elm Street is no longer an exploration. It is now an indictment, of Memory.

]]>

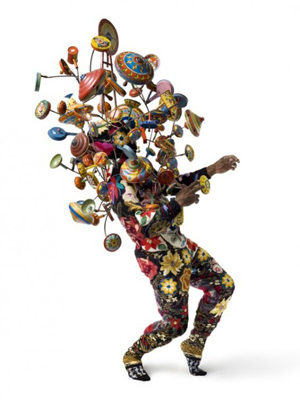

Nick Cave, recent soundsuits, installation view via endless lowlands

Trash is the one thing people, most emphatically, are not. Though the plight of an individual wearing trash is real, the vision of it seems like a crass and cruel joke. It is beyond sarcasm, more primordial, in its rendering of “regalia.” It is haute couture’s opposite. It is as close an analogue to the work of sculptor Nick Cave as we are likely to get.

Born in the 50s, Nick Cave was raised by a single mother in Missouri. He is black. He learned to sew in Kansas, but after watching Alvin Ailey perform, he realized his calling was performance. You should realize by now that he does not moonlight as an affectedly-gritty Australian pastiche-balladeer, that’s a different Nick Cave.

When the sculptor / performer Nick Cave first emerged from obscurity around 2006, fashion and art critics loved him for different reasons. He was still on probation when it came to his relevance, but he had an advantage over his contemporaries because he didn’t bear the curse of contemporary art, namely that it is very easy to walk past most of it. It is not at all easy to walk past one of Nick Cave’s “soundsuits.” Meanwhile, fashionistas would tousle his hair with comments like “What in God’s name is that?” in their blogs and magazines, and they loved him precisely because he was never really one of them. They never imagined that he threatened the status quo, but he does.

Nick Cave, Untitled Soundsuit, via digezine

Sculptures cannot be shut off like concert recordings, or closetted like gowns. They’re always on, and in a funny sense, however welcome the masterpieces of Michaelangelo might be in the museums of Europe, sculpture is defined by being sort of in the way; even in the case of ceremonial attire, whose DNA Cave says is present in his soundsuits. The ceremonial sculpture / costumes of Africa, whatever their vicissitudes of design and significance, were shaped to tell people: this is not what people look like. Something else is going on. His message comes with a painful twist: some of us have no tribe, and no hope.

Cave is the head of the fashion design department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. That said, the most helpful avenue to take when appreciating Cave is exploring how he is a sculptor and not a fashion designer. As outlandish as his clothes may look, they will not melt into mere novelty. Nor do they submit to the built-in obsolescence of the “fashion industry” as such. In the fashion world proper, a gown speaks for a specific season and month of a certain year, but sculpture is about timelessness.

Nick Cave, Untitled Soundsuit via UCLA

On the surface, a soundsuit made of disused socks might ask “What happens to the refuse of style?” Nick Cave addresses that but goes further, elevating the question to the level of cosmological inquiry. Because he’s concerned not only with discarded fabrics, but also with the musical instruments thrown from the progress of culture, the sticks thrown out by forests, the most meaningless and forgotten images in dreams. His soundsuits are not only in the way, they make noise and they cannot be ignored. More than that, they insist on causing their audience to rejoice. As indicated by the original title of his show, Meet Me at the Center of the Earth, Cave invites us into a no-holds-barred confrontation with anthropology. He is trying to reveal the proto-ceremony of which all other primitive ceremonies were echoes, the spastic dance of exuberant creatures trying, and failing, to find the true rhythm of matter, energy, and sound.

]]>

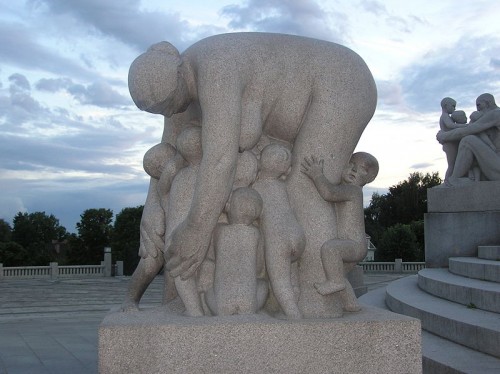

Vigeland Sculpture Park, Oslo. detail photo: Roberto Frison via wikipedia

Entering Vigeland’s statuary garden, the visitor is greeted with smooth statues of nude men and women in more-than-intimate contact with naked children. Naturally, an inner alarm warns us not to trust our first instinct; these are not statues of pedophiles. We force ourselves into an attitude of mature appreciation, but as the statues graduate from a naked man holding two children under his arms to more garish and off-putting displays of familial intimacy (two identical twin sisters in a lesbian embrace, a bearded man beating a naked teenager, which I’m told represents a cherished Norwegian ideal of fatherhood) the effect of Vigeland’s passionate misreading of Rodin becomes, for lack of a better word, “icky.”

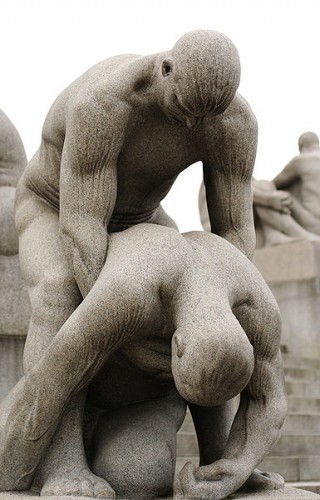

Vigeland Sculpture Park, detail. photo: Bob Marit, via wikipedia

Though it is too easy to giggle at the wrestlers, contorted with exertion, that statue is the exception that proves the rule: while the former was just a naive representation of athletics, the rest of the statues actually deserve our initial knee-jerk reaction. Especially once we get to the man grinning at us while pinching his own nipples. It is impossible to deny the beauty of the statues, but the smoothness Vigeland was expectorating was not solely his own; the Norwegian government, which sought always to be represented as untroubled, non-violent and as a country without trolls, was no doubt the original source. This Will-to-Smoothness was so desperate in Vigeland’s patrons that he used this park to purge it from himself: it is peopled by things which look smooth but are not smooth. There are other parallels with Ibsen, as we shall see.

Where Rodin studied the dynamic of Man and Woman, Vigeland celebrated a fantasy of family with a daemonic muse of something richer and stranger than naïveté. I’ve called this place “The Inappropriate Garden” and have wanted to visit it for years, picturing whole families staring at the statues in puzzlement as I have always imagined the French might stare at Beckett plays. But that, of course, is not how it plays out in practice. The smoothness has caused the statues’ message to slip beneath the consciousness of the observer. They are not transfixed by disquiet, they’re laughing and taking pictures. And they are touching each and every slab of granite.

Vigeland Sculpture Park, detail. via visitoslo.com

And it’s natural to want to touch them. They were made to be touched. They possess an appealing texture which owes, really, to the way in which this national commission was completed. Time being a factor, the actual stone-carving was transferred to professional artisans, and, for this reason, and to preserve the granite’s natural sense of volume, simple designs were the most practical. Perhaps this always accompanies expectoration in the arts –a conspicuous practicality that covers for operations of the artist’s unconscious. The utopia imagined here is all about the tactile possibilities within “the family” and the Vigeland – who was famous also for the creation of Hellscapes, and who made money by depicting battles of men against lizards and serpents – is not trying to disguise the tormented machinery therein. He is retching it forth, and the smoothness here does for sculpture what Ibsen did for drama. It’s a cousin of irony: You’re saying these people are smooth?

More boldly, Vigeland is to Rodin what Ibsen is to Strindberg: a version so well-oiled that the machinery of torment, which screeches elsewhere, is silent. To shake Hedda Gabler’s hand is to feel the perfectly warm touch of a human woman. We do not leap back from her as we do from a Strindberg grotesque. Nor do we flee, or even feel, really, the sights and shapes of human heaviness at work in Vigeland’s park. Instead we are left with finely crafted forms, pinching themselves beneath their smooth polish of stone.

]]>