…graves at my command

Have waked their sleepers, oped, and let ‘em forth

By my so potent art.

— Prospero; The Tempest Act V Scene 1

An Irish ballad written in the mid-nineteenth century tells the story of a drunk named Tim Finnegan, who was taken for dead after falling from a ladder in an alcoholic daze:

[They] laid him out upon the bed

With a bottle of whiskey at his feet

And a barrel of porter at his head.

When his mourners get to drinking, the wake devolves into a town-wide brawl: “woman to woman and man to man.” Eventually a flying whiskey bottle shatters just above Tim’s corpse and, drenching him, revives him from death:

Timothy rising from the bed,

Sayin’: “Whittle your whiskey around like blazes!

Thanam o’n Dhoul! D’ye think I’m dead?”

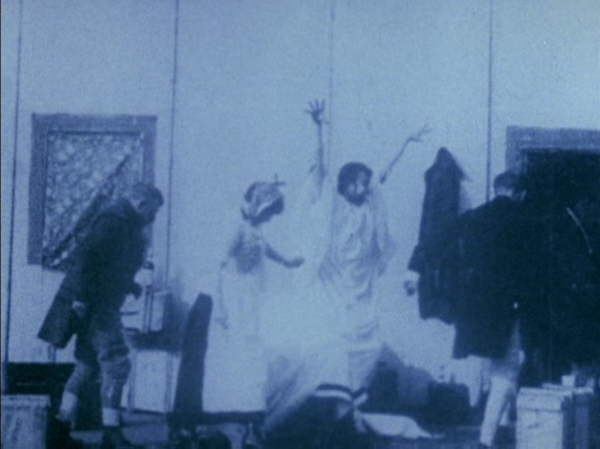

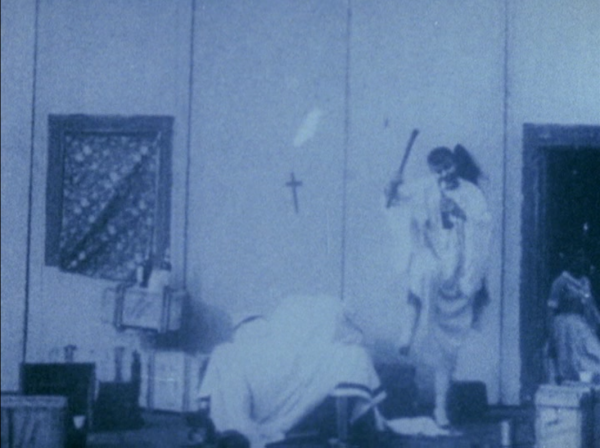

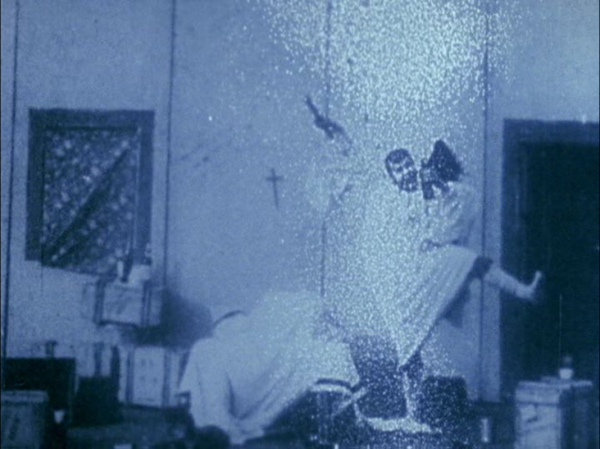

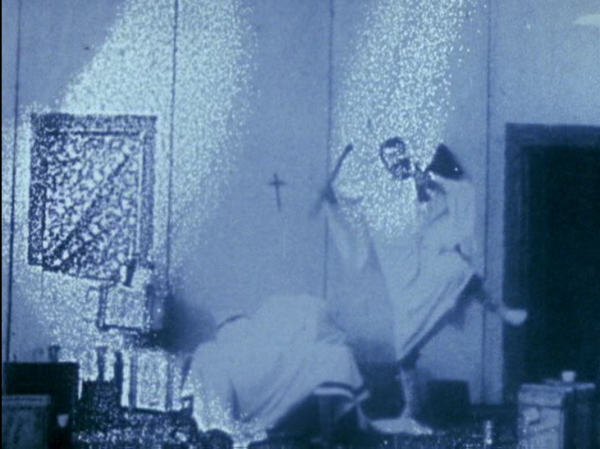

In the silent-film re-enactments of “Finnegan’s Wake” that bookend Hollis Frampton’s 1979 short Gloria!, the ballad’s story plays out in broad, puppet-like gestures: dancing, weeping, fighting, limb-flailing. When Tim wakes near the end of the final clip, he waves his arms around like a boogeyman and sends his well-wishers scattering away. Left nearly alone in the frame, he kicks the last mourner out the door, raises his fists to the ceiling and leaps around triumphantly, clutching a bottle in one hand and a club in the other. These clips bookend two longer episodes. On a solid green screen, scrolling digital text spells out a series of sixteen “propositions” about Frampton’s maternal grandmother—including that “she remembered, to the last, a tune played at her wedding party by two young Irish coalminers who had brought guitar and pipes.” We then hear, against a now-empty green screen, that same tune played from start to finish.

Gloria! was the last completed component of an intended thirty-six-hour-long film cycle inspired by the travels of Magellan, whose literal attempt to “encompass all human experience,” as Frampton once put it, corresponded to the director’s own compulsion to leave no subject unfilmed, no technique untried, no medium unexplored. The film found Frampton looking forward in multiple senses: eagerly adopting new technology (digital interfaces; computer-generated text) and frankly anticipating his own death. At the same time, Frampton’s circumnavigation of human experience ended up taking him back to his earliest childhood memories, his family history, and the origins of cinema itself. Gloria! begins and ends with a resurrection: a moment when, there being no more future to anticipate, life rewinds itself and begins again.

How is it possible, Frampton seems to be asking, to organize something as elusive and circuitous as memory into sequential thoughts? Frampton’s attitude toward remembrance in Gloria! is almost mathematical, as if the past were a series of facts to be manipulated and derived. At the same time, he’s careful to distinguish between the mushy, vague language with which we often talk about memory and the ambiguities built into memory itself: “these propositions are offered numerically,” reads the first line of onscreen text, typed out in start-stop keyboard rhythms, “in the order in which they presented themselves to me; and also alphabetically, according to the present state of my belief.” The structure(s) of Gloria! are meant to account in equal measure for time as it exists in the abstract—a linear, unbroken, one-way progression of minutes, seconds, and hours—and for time as it’s actually experienced by those subject to it: jumbled, overlapping, doubling back. The tension between these two competing structures is, Frampton suggests, essential to the logic of memory, where every moment exists in theory as a single, unrepeatable entry in a linear sequence, and in practice as something stickier, more resonant, available to be savored and returned to at length.

It’s also, by extension, the logic of the movies, which remind us of the temporal distance separating us from their subjects even as they make the past seem like something tangible and close. It’s possible for us to be so swept away by this second illusion that we forget the fact that precedes it; so taken with a film as it plays itself out in the present, our present, that we overlook its essential point of origin in the past. Occasionally, a cut will cue us into the illusion, remind us that the footage we’re watching isn’t so much a natural emanation of the present as a re-animated, re-assembled product of the past, stitched together from moments of dead time. I’m thinking, for instance, of the abrupt leap in Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln from a springtime courtship to a graveside vigil, or the cut late in Ozu’s Late Spring that displaces a moment of father-daughter tenderness in favor of the daughter’s marriage to an unseen and unloved groom. There is something cruel, final, and decisive about these cuts; they are about the impossibility of clinging to the present and the equal impossibility of returning to the past. Just as Lincoln can never revive his beloved, we can never return to that moment when a young Henry Fonda stooped by a studio-built grave at the behest of a pre-Searchers, pre-war John Ford.

The computer-generated text that occupies much of Gloria! deals in concrete, vivid details: we learn that Frampton’s grandmother kept pigs in the house, though never more than one at a time; that she hailed from Tyson County, West Virginia; that she was obese; that she taught her grandson to read; that she “gave him her teeth, when she had them pulled, to play with”; that she gave birth to nine children, four of whom survived (all daughters); that she was married on Christmas Day at age 13; that, when the filmmaker-to-be was three years old, she read him The Tempest. And yet these bursts of digitized text, even as they point toward a specific point in time, keep that point at a threefold remove: by the time we encounter that woman reading Shakespeare to her toddler grandson, the scene has been filtered through Frampton’s imperfect memory, abstracted into a series of words and phrases, and digitally rendered by a process that further abstracts those words and phrases into streams of numerical data. With Gloria!, Frampton was anticipating a time when information about the physical, time-bound world would be stored outside that world, in an immaterial digital space made up not of ink, matter, or sound waves but digits and pixels. But he was also, I think, encouraging us to consider that scene between grandmother and child as if it existed independently of any one set of digits, pixels, letters, words, or grains, in a space outside of time. The paradox, he suggests, is that such a space—if it did exist—would only ever be accessible to us through a material, time-bound medium.

Shakespeare critics have often taken Prospero’s abjuration of his magic near the end of The Tempest for the Bard’s own thinly-veiled farewell to the stage. If it is a goodbye, though, it’s also a kind of celebration. On Prospero’s part, it’s a statement of faith in the power of the wizard’s art to provoke storms, dim the sun and raise the dead (sixteen centuries after Lazarus and two before Finnegan). And on Shakespeare’s part, it’s a statement of faith in the power of words—if not to resurrect the dead, then at least to call forth their ghosts. The autobiography in Gloria! is both more explicit than that of The Tempest and subject to more layers of ironic distance. Even Frampton’s coming-to-terms with the idea of autobiography is winkingly impersonal: “she convinced me, gradually, that the first-person singular pronoun was, after all, grammatically feasible.” But no amount of tongue-in-cheek detachment or digitally-imposed distance could conceal the flesh-and-blood woman at the film’s center, who once scolded her three-year-old grandson for liking Caliban best out of all the cast of The Tempest, and who lives on in a space where time-bound images blur into computerized text: a brave new world that may or may not also be a world long gone.

]]>

The House Is Black (Forough Farrokhzad, 1963)

Extreme affliction, which means physical pain, distress of soul, and social degradation, all at the same time, is a nail whose point is applied to the very center of the soul… He whose soul remains ever turned towards God though the nail pierces it, finds himself nailed to the very center of the universe.

– Simone Weil

The House Is Black opens with a zoom and ends with a retreat. At first we can’t see a thing—we need to be prepared. “On this screen will appear an image of ugliness,” a male narrator tells us, “a vision of pain no caring human being should ignore.” After a moment of silence and darkness, a woman’s face appears, or something like a face. We flinch; the camera doesn’t. It zooms in, holds, and holds some more, urging us to look. Twenty-two minutes later, the camera recedes, this time away from a large crowd. A gate clanks shut in its wake bearing two hastily scrawled words, less a name than a warning: “Leper Colony.”

Forough Farrokhzad made The House Is Black in 1963, during a twelve-day stay in the Baba Baghi Leprosarium. It is, or was, a small outpost on the outskirts of Tabriz, in the East Azerbaijan province of Iraq’s mountainous far north. As shown in The House Is Black, Baba Baghi is a place of dust and brick; the walls are whitewashed, the trees dead. Scattered leaves float in pools of standing water. In the streets people dance, laugh, play games, scuffle. Kids run around and hurry to school. We almost forget their flaking skin, their missing hands and feet, their drooping lips. We never really forget, though: their suffering is too close, too visible, too present. Here, affliction touches everything.

***

Three voices make themselves heard in The House Is Black. The first is a man’s, careful, steady, precise. He tells us what leprosy is, that it’s chronic and contagious; that it eats away at the body, blinds, deafens, invades. What kind of world this is in which leprosy exists, what these men and women did to deserve their affliction, doesn’t interest him, at least not directly. Two thoughts guide him: that suffering exists, and that we ought to stop it. “To wipe out this ugliness and to relieve its victims,” he tells us before the film’s first shot, “is the motive of this film, and the hope of its makers.”

“Leprosy goes with poverty,” we’re told. It destroys the body, but it also sections off its sufferers from the social world, crosses them out from the books. They aren’t just afflicted, they’re ignored. Simone Weil, in her essay “Forms of the Implicit Love of God,” imagined the marginalization of the poor and afflicted as a steady process of de-humanization, the sole thing capable of reducing a human being to “the state of an inert and passive thing.” True charity is to return the afflicted their humanity, their claim to justice, even their very existence; it is also, conversely, an act of self-sacrifice, a conscious choice to take up “a share in the inert matter which is [theirs].” Before she even had a chance at dignifying her subjects, Farrokhzad had to risk sharing quite literally in their affliction: leprosy is contagious, and it’s hard to watch The House Is Black without thinking how great a risk it took just to keep the camera rolling inside those walls.

That risk taken, Farrokhzad found herself with another challenge: how to film the afflicted so that they inspire not just pity or respect, but affection. It’s easy to consider these lepers as noble, painted icons of suffering. It’s harder to see them as people with whom one might converse, argue, or crack jokes. Those of us who make it through the first shot of The House Is Black will have acknowledged these lepers’ presence; now we must recognize their humanity.

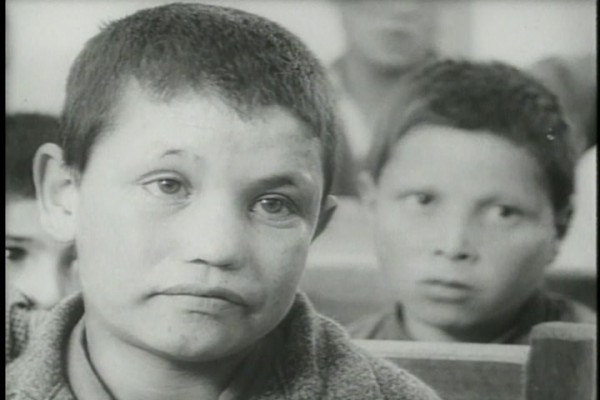

Farrokhzad’s first step was to have the afflicted speak for themselves. Their collective voice, the second of the film’s three, might come from many speakers, but it has a common theme. Toward the end of that first shot, we hear a young, pockmarked boy praying out loud. “I thank you, God…” he reads. “I thank you for creating me.”

Once we give these lepers our attention, we might expect them to protest their lot, to demand attention from a society that’s long ignored them, to say to all who might listen, we don’t deserve this. Some of us might even want them not to stop at their fellow men: why not go to the ultimate source of their affliction, bring their complaint to the feet of God? That, having been given a platform from which to speak, they choose instead to supplicate themselves before God, demanding nothing and accepting everything—and with gratitude, no less—is beyond comprehension. Was Farrokhzad, in giving these lepers the right to demand justice, really giving them the opportunity to renounce that right all over again, this time of their own free will.

If there’s one lesson to be gleaned from The House Is Black, it’s that the afflicted don’t always think or act as we expect them to—that they often refuse to play the role of the dignified victim. Theirs is a community forged by affliction, but not necessarily defined by it. To respect the inhabitants of Baba Baghi as free agents like ourselves, not just lumps of pitiable flesh, means to honor their intentions even when they seem voluntarily to shrug off the very rights Farrokhzad has been trying to win for them. What if they don’t care for rights, claims, or complaints? What if they don’t even care for justice as we might define it—or, still more bafflingly, what if they find their situation just? Charity is quick to point fingers in favor of its charge; it takes a very different sort of empathy to grasp that life, seen through the eyes of the afflicted, might be something to receive not with indignation, but with gratitude.

“I thank you for giving me eyes to see the marvels of this world,” prays one young boy, squinting through drooping eyelids. Farrokhzad gives us a tall order: to see in the dusty alleys and ramshackle streets of Baba Baghi what that boy sees, to trade our way of looking, and feeling, for his. The House Is Black does more than challenge us; it overrides us, beats us down. It can never do so fully, of course, and that failure on the part of the film to make us see anew is really a failure, inevitable but disappointing, on our part—a failure to see these lepers as they see themselves, as defined by something apart from their affliction. It is, ultimately, a failure of empathy. Still, there are occasional breakthroughs: in one late-film scene, we dart with Farrokhzad breathlessly from team to team in a children’s soccer game, hooking, diving, hopping, bouncing around. Maybe at that instant we’re capable of forgetting the kids’ affliction, or at the very least of letting it slip off to the background, replaced by the arc of a soccer ball in mid-air, the rush of bodies through space, the fall of light on hair and skin.

There are limits to identification. We want to demand relief for the meek and afflicted–all the more so if, out of their unconditional love of life, they never demand relief for themselves. The more these lepers consider themselves blessed, the more inclined we are to take count of their blessings and find them lacking. The House Is Black, then, is a film torn between two diverging desires: the desire to identify with the afflicted so completely as to take on their way of seeing, and the desire to defend them from the balcony, to argue their cause to the world. Both find an uneasy balance in the film’s third voice, Farrokhzad’s own. That’s her in an early scene, looking on at a schoolroom of leprous children knee-deep in prayer, asking a question that is really a challenge: “Who is this in Hell praising you, O Lord?” In other words: Who in Hell would praise you? Or perhaps: Why would those who praise you be in Hell?

The voice belongs to Farrokhzad, but who’s speaking? Sometimes first-person, sometimes third, neither internal monologue nor outsider testimony, at once collective and personal, this third voice seems to float from speaker to speaker, subject to subject, soul to soul. It’s the voice of a community, but also of its defenders, including those behind the camera. It tends to appear over footage of nature, perhaps recalling Christ’s prediction that if his disciples fall silent, “the stones themselves will cry out”; though if they cry now, it’s likely more out of sorrow than joy. Late in the film, an aging, one-legged man hobbles toward the camera, framed by rows of trees, backed by the setting sun. Meanwhile, Farrokhzad reads a few verses, derived from one of Isaiah’s especially pained laments:

Alas, for the days are fading,

the evening shadows are stretching.

Our being, like a cage full of birds,

is filled with moans of captivity.

And none among us knows how long he will last.

Like doves we cry for justice…

and there is none.

We wait for light, and darkness reigns.

There’s not much anger here, and what little there is, it’s muted by a sorrow so profound and so total that it doesn’t allow for righteous indignation. But it’s a sorrow suffused with hope, and made still more acute for it; in the high-contrast, black-and-white world of The House Is Black, patches of shadow look all the darker next to comparatively blinding streams of light. The two seem often at odds, sometimes ill matched: in this instance, that one-legged man marches toward the camera until his body engulfs the frame in dark. For a few seconds, we hear only the repeated clanks of his walking stick. Then, a child’s voice, reading aloud: “Sometimes at twilight we see a bright star.” For most of The House Is Black, light and dark are present onscreen in equal measure, vying for control, but perhaps the lepers’ condition can best be expressed by light’s absence, or at least its deferral—by light as something not yet attained, but longed for, glimpsed, and expected.

Near the end of the film, a child sitting in class is asked to name a few beautiful things—the moon, the sun, flowers, playtime—and another a few ugly things. “Hand,” he replies, giggling, “foot, head.” A third has to come up to the blackboard and use the word “house” in a sentence. He hesitates, turns, and slowly writes out, the house is black.

There are many films in which the beautiful and ugly coexist, and many that propose some way of easing the resulting tension, whether by giving one the last word, or (less frequently) by reconciling the two. The House Is Black doesn’t propose a thing. It’s a film not about striving, ascending, or transcending, but about waiting—sometimes patiently, sometimes fitfully. There is beauty, but not enough to compensate for affliction; hope, but no sign of its fulfillment. No sign even of an object on which hope could settle, any potential source of grace.

Well, maybe one. If in watching The House Is Black we witness and even briefly participate in the giving back of humanity to the afflicted, if it was by filming these lepers that Farrokhzad managed to return them their dignity, if not their health, then perhaps The House Is Black is in some meager and incomplete way its own source of grace. For twenty-two minutes, these men and women have the chance to see their shattered bodies re-written in light—if only on a screen, by the flickering glow of a projector. They haven’t been healed, but they’ve seen their present sufferings reproduced in a new, immaterial substance, one untouched by bodily affliction. It isn’t a solution, but it might at least be a promise.

]]>