via arbroath

Developing Animals: Wildlife and Early American Photography

Matthew Brower, Minnesota 2011

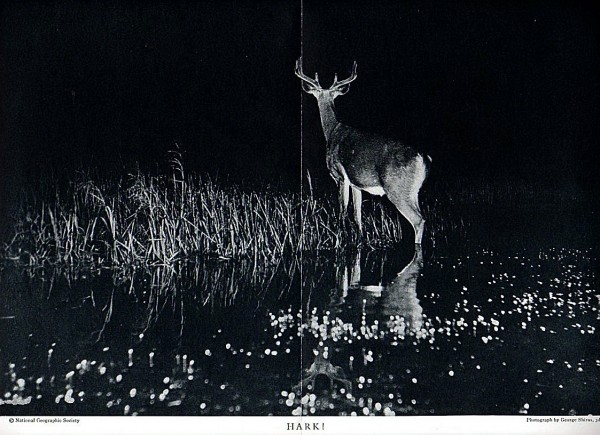

In the summer of 1906, National Geographic was in a state of uproar. The magazine’s pioneering editor, Gilbert Henry Grosvenor, despite protests from the board and editorial staff, had taken the magazine in a radical new direction. Rather than the magazine’s typical format—dense text punctuated by a few illustrations, the July issue included 74 photographs, taken from a former Congressman’s recent exhibition, and very little in the way of actual writing. Two members of the society’s board quit in disgust, claiming that Grosvenor had “turned the magazine into a picture book.” They could have saved their breath. The July issue was one of the most popular of the magazine’s history, cementing the role of photography in nature-focused publications. The photographer at the center of the controversy, George Shiras III, became one of the pioneers of American wildlife photography.

Shiras’ subject—deer caught in their natural habitat—wasn’t new. As Matthew Brower extensively proves in the opening chapter of Developing Animals: Wildlife and Early American Photography, animal photography dates back almost to the invention of the camera. In the 1850s, Victorian photographers, lacking the technology to capture live animals on film, took pictures of stuffed stags posed in woodland settings. By the time Shiras began photographing animals in the 1890s, dry-plate film, focal-plane shutters, and other innovations had made it possible to take pictures of subjects who weren’t willing to sit still for several hours. For the first time, images of animals outside of captivity became widespread. The first pictures of animals in the wild were taken by hunters and other gamesmen, who snapped photos of their conquests. Though for some of these camera-hunters the photograph itself was sufficient trophy, others simply snapped pictures of their prey before killing it. (One particularly dedicated hunter attached a camera to the end of a rifle in order to get pictures of his game as it was being shot.) Shiras, an avid woodsman, self-identified as a camera-hunter. Like other camera-hunters, he used tracking techniques to obtain the first photos of deer at night. Shiras would whistle to the deer to get them to turn around, blast them with a jacklight, open the shutter, and let loose with an enormous magnesium flash.

via api.ning

The resulting photos look today like poorly-done Xeroxes—high-contrast images with huge swaths of darkness, the light from Shiras’ jacklight reflecting from the terrified deer’s corneas—but they mark a shift in the way Americans thought about wildlife photography. Before Shiras’ series, photographs of wild game were inextricable from the photographer’s reputation as a hunter. But Shiras’ work was heralded in salons in Paris and art shows for its aesthetic prowess, even earning a name-drop in one of Ernest Hemingway’s short stories. The photographs no longer functioned as trophies, but as records of animal life, glimpses into the natural world unsullied by humans. And this, for Bower, is where the trouble begins.

Though Shira’s work bears a clear imprint of human intervention—the frozen looks on the deer’s faces, the imposition of artificial light on a night-time habitat—his photographs pioneered a kind of wildlife photography that detached the human sphere from animals entirely. “The change from camera hunting to wildlife photography has been marked by a change in the function of animal photography from asserting the presence of the photographer to denying it,” Bower explains. This idea rankles, and most of Developing Animals circles around how and why we present animals in roughly the same way Toy Story presents Mr. Potato Head dolls: They’re only really alive when we’re not there. “According to the logic of the wildlife photograph, the real animal is not the one we see,” Bower writes. The assumption is that animals in settings where humans interact with them—on safari or in zoos—act differently than they would in the wild. Their behavior is different than when we aren’t watching them. He traces the origin of this separation to the Garden mythos, the idea that, since Eden, humans have ruined everything they’ve touched. And so, wildlife photographers must act as part-spy, part-magician, collecting information about animals that would otherwise be inaccessible to us.

Every staple of wildlife photography today—from the photographic blind to the telephoto lens—is, in Bower’s view, designed to maintain the line between wild animal and human. Bower has a particular grievance with the photographic blind, which he describes as a “reverse panopticon;” “a machine for controlling the relation between seeing and being seen.” The power dynamic of visibility versus invisibility is at the heart of wildlife photography. The whole idea is that we see animals even as we can’t see them, and if the animals could see you, the whole enterprise would somehow be a sham. “Wildlife photographs construct their viewers as unnatural…they suggest that our presence makes them inauthentic.” Because the way we see wild animals is, unless you happen to live in a national park, primarily shaped by photographs, it follows that wildlife photography has an enormous role in human-animal relationships. Ever since Shiras, the overwhelming message of wildlife photography has been simple: Photographs offer you access to the secret, real lives of animals. Any other animal-human interactions are contrived and false.

This is, of course, simply untrue. While the conservationist aspect of this way of thinking may benefit wildlife and their habitats, the artificial separation between humans and animals is patently false. Brower’s conclusion is apt, though you have to wade through several dense chapters of clunky academic writing to get to it: “I want to insist that human beings are part of nature and that…it is a conceptual mistake to accept the framing of wildlife representations that nature is something we can only authentically encounter from the outside.” In other words: forget about Eden.

Though Developing Animals gives a thorough—at times, excessively thorough—account of 19th and early 20th-century American attitudes to animals as shown through photography, it stops short before the explosion of wildlife-based entertainment of the last 40 years. Though most television programs maintain the distance between humans and animals—unless a human is actively being eaten by animal—there has been a recent uptick in programming that focuses on human-wildlife interaction. Ever since the dazzling, outrageously expensive nature documentary series Planet Earth became a staple in every college stoner’s DVD collection, our taste for gently narrated wildlife shows has been piqued. Channels like Animal Planet and Nat Geo: Wild have been competing to provide the next exciting nature show, combining tropes of reality television with animal-watching. Shows like Swamp People, which traces a group of Cajun alligator-hunters, and River Monsters, which follows an extreme angler, are a conceptual return to the days of camera-hunting and Shiras’ less-than-sporting techniques.

In this, what Developing Animals elucidates is a still more interesting shift: not only do we now document wildlife as if they were people, we’ve begun to document people as if they were wildlife. The techniques of wildlife photography are the new tropes of reality programming: you don’t really know who someone is unless you’ve seen them followed around by a camera for several weeks. The implied separation between the cast of Jersey Shore and its audience is as similarly problematic as the assumption that humans and animals live in separate realms. Of course, unlike baboons and meerkats, Snooki and the Situation are perfectly able to communicate and consent to photography. Whether either group is acting authentically is another question.

Jersey Shore, via igossip

Wildlife photography and reality television at their best serve the same function: They give us a chance to glimpse things we might never have gotten to, and they remind their audience how varied, strange, and wonderful the world is. National Geographic now serves not only as a dazzling compendium of photography, but as a reminder of just how much life there is out there. The folly in both is to pretend that the person behind the camera doesn’t exist. No matter how pristine those tigers appear, there was still a person there, somewhere, taking the picture. Even when we don’t interact with them directly, the habitats of animals and humans are inextricably linked, a fact that usually only gets attention when one species or another is dying thanks to poaching or acid rain or logging in the rainforest. What Bowers shows in Developing Animals is that, despite the distance imposed between humans and animals in wildlife photography, what we’re really recording is ourselves.

]]>

The Wades' dining room. Carolyn made the chandalier; the ghostly figure seated at the table was part of Margot's fall show. Photo: M. Eby

“Museums are places where art goes to die,” Alan Watts once opined in Artforum, and he’s hardly the first art-lover to think so. Many contemporary artists have frought relationships with museums as institutions: No matter that great works are collected and cared for, no matter that landmark sculptures and paintings are impeccably preserved in temperature-controlled room, protected from camera flashes and finger oils by watchful guards, something about the museum forever alters the interaction between the art and the public. Les Demoiselles D’Avignon, viewed alongside the works of Van Gogh and Matisse, doesn’t have quite the revolutionary spark that it did in the salons of Paris. In the stifled atmosphere of the museum—don’t sit on this, don’t touch this, don’t speak that loudly—things begin to acquire a certain glazed over look; the life-force ebbs out of them. In 1961, pop artist Claes Oldenburg wrote a manifesto that neatly articulated the frustrated relationship he and his contemporaries had with the museumification of art:

I am for an art that is political-erotical-mystical, that does something other than sit on its ass in a museum. I am for an art that grows up not knowing it is art at all, an art given the chance of having a starting point of zero… I am for the art of underwear and the art of taxicabs. I am for the art of ice-cream cones dropped on concrete. I am for the majestic art of dog-turds, rising like cathedrals… I am for the art of things lost or thrown away

Integrating this interactive element of art into the museum space has been one of the challenges of curators of modern art museums, the brass ring institutions like MOMA and the Brooklyn Museum are leaping for.

The entranceway ceiling, dotted with snakes and chairs. Photo: M. Eby

But how do you construct a museum without the attendant effects of museumification? Birmingham-based artist Margot Wade discovered an elegant solution to this paradox: Keep living in the art. Wade, a recent graduate of Mount Holyoke, is turning her grandparents’ house into a museum, one that’s partially dedicated to her grandparents’ impressive art collection and partially a monument to her family history. Robin and Carolyn Wade will continue to live in the house and admit curious museum-goers twice or three times a week, who will take an audio tour through the house and hear family anecdotes. Margot decided to go easy on the art history because, well, it’s just not as interesting as the way her family has interacted with the art. Take, for example, the Santa Claus-shaped chocolate butt plug her grandparents have in their collection. “We could talk about the artist’s intentions,” Margot said, “or we could talk about my uncle’s reaction when we were all eating dinner with a chocolate butt plug on the table.” Another chestnut is about a human skull that Carolyn brought home on one of her expeditions after bargaining with cannibals. At one of the Wades’ parties, a guest unwittingly used it as a bowl for dip, much to Carolyn’s horror.

The Wades' den. Photo: M. Eby

Clearly, this is no ordinary grandparents’ house. Robin and Carolyn Wade’s house has been a point of local curiosity since they began collecting art in the 1980s, eventually allowing local artists free reign in various rooms. When you arrive at the house, you’re greeted by what looks like a gargantuan mechanical spider and a couch shaped like a pair of lips; the ceiling of the entrance hall is covered in upside-down chairs and painted Styrofoam snakes. The kitchen ceiling is encrusted with twisted pots and pans; above the garage a series of mannequins writhe under pink insulation paint. (That piece, called Crime Scene, originated when the garage had a leak and Robin and Carolyn liked the way the insulation looked. At night, lights illuminate the “bodies,” which look to be trying to escape from the roof..) Every possible nook of the house is stuffed with artwork, curiosities, mementos from traveling, and photographs of the Wade family.”People used to drive up and just ask to see the house,” Margot said. “I’ve had to give so many tours; I know what story goes with what piece.” Some of the artwork has attachable “penis flaps” to obscure genitalia for more conservative visitors. I had been in the house before—Margot is a high school friend of mine, and Robin and Carolyn generously hosted many art class field trips—but as Margot gave me a tour of the museum-in-progress, it was difficult to focus on any one part of the house. Here was a garage full of stuffed animals Robin had bagged over many years, here was a Kiki Smith drawing next to a series of paintings by Carolyn’s art class, here was a Rauschenberg drawing hanging along the staircase, here was a Franz West chair people actually use for sitting in, here was an enormous stuffed bear next to a coat so angular it would make Lady Gaga blush. The effect is dizzying, even before you get up to the attic crammed full of art and art materials.

Steps leading to the attic. Photo: M. Eby

“My grandparents are packrats,” Margot explained, “They save everything. So when I first started to go through all this, a year ago, the attic was so full of boxes that I had to just start making little rat trails into it.” At one point, Margot had to throw boxes of Christmas ornaments out the window, since the struggle to get back down the attic stairs seemed impossible. The treasures she excavated are an antiquities specialists dream: safety goggles, lighting fixtures, dusty leather-bound ledgers, linens, porcelain figures, a cabinet full of 1950s hardback books and animal skins, bags of newspaper clippings, needlework, accidental and on-purpose action paintings, maps of the world, hand-made lace, bejeweled insects, ball gowns, scraps of wallpaper, suitcases, a pile of mannequin parts, NRA badges, dessicated black-eyed peas, and paint long ago turned to powder. When the museum is done, Margot will display some of these alongside the art work; she plans to make the attic into a “white cube” where people can watch recordings of themselves looking at the art downstairs, a wink to the museum culture that Margot is pitting herself against.

A pair of Franz West chairs, for sitting. Photo: M. Eby

When the museum opens, it will be a combination of folk art and high art, a family cabinet of curiosities that combines the wonder of your grandparents’ attic with the experience of seeing a famous work of art. “It’s my favorite collection, and people need to know that we have this in Birmingham. We have Louise Bourgeois, and a Frank Gehry chair, and Kiki Smith.” But it’s also about everyday treasures, Margot said. “It’s about finding something and saying, look, Grandaddy, I found this picture you’ve been looking for for 30 years. It’s a memorial, monument, and museum. But it’s also the ultimate way to say ‘thank you.’”

]]>

Clarksdale, Mississippi via Wired

Clarksdale, Mississippi isn’t much of a convention town. Tucked into the north of the Mississippi Delta, about an hour’s drive from Memphis, the town has an official population of about 20,000, but even that seems like a stretch. No stores stay open after five, and there’s not much activity downtown between Sunday night and Wednesday. It’s barely more than an oasis amidst miles of neatly groomed cotton fields, rows of stubbly plants interrupted only by gleaming metal catfish tanks and the odd piece of farm equipment. Getting there requires an active imagination and a detailed map. The surest sign that you’re approaching is when the AM radio suddenly shifts from static and Glenn Beck sermons to the sound of Hammond organs and B.B. King. Clarksdale is a blues town, one of the required stops along Highway 61 for music history buffs. It’s a town with a tourist economy based on ghosts: Ike Turner grew up there, as did Sam Cooke. Bessie Smith died in downtown Clarksdale after a car crash, and Robert Johnson supposedly sold his soul there to learn how to play guitar. The whole place is awash in tall tales, carefully preserved memorabilia, and historical markers. If you judge Southern-ness not by geography but by a penchant for anachronism, a certain over-zealousness for preserving the past, than Clarksdale is the most Southern place on earth.

Which is why The Oxford American, a Southern literary journal based in Arkansas, chose Clarksdale as the site for their weekend-long shindig, a convention/festival/editorial vacation on July 9th and 10th entitled “The Most Southern Weekend on Earth.” The hundred or so intrepid festival-goers who descended on downtown Clarksdale managed to book out all the hotels and swamp the afterhours juke joints. Most of the Southern Weekend events were staged at Ground Zero, a newer blues club with a carefully curated rundown look opened by Clarksdale native Morgan Freeman—most of the locals refer to it simply as “Morgan Freeman’s place.” Along with ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons, Freeman has been instrumental in the marketing of Clarksdale as a Southern tourist spot—a piece of authentic blues history, still kicking, still accepting donations. Both Friday and Saturday at Ground Zero, The American booked a lineup of blues musicians and bands that grew up listening to them. The first night featured Jimbo Mathus, another native known chiefly for his big band revival outfit the Squirrel Nut Zippers. His act was a kind of bizarro musical, a washboard-strumming folk band that, dressed in what can best be termed as Appalachian chic circa 1875, told the history of Mississippi from the Civil War on up to “Wild Bill Faulkner.” The headliner of the night actually played first—Robert “Wolfman” Belfour, R.L. Burnside’s protégé, now closing in on 70. His music had a country twang, the blues washing over the crowd as they moved in to watch Belfour patiently coaxing long wails from his guitar.

Saturday’s Southern activities included a tamale tour—one of the culinary vestiges left by the wandering Hernando De Soto on his way further South—and a Q&A with music writer and Elvis buff Peter Guralnick, and Oxford American editor-in-chief Marc Smirnoff, in which Guralnick revealed tidbits about Jerry Lee Lewis, Charley Patton, and working for Rolling Stone. Later in the afternoon, Daniel Bradford, publisher of All About Beer, led a Southern beer tasting, and inspired in this reporter a renewed appreciation for Budweiser as the world’s preeminent Bohemian light lager. But the main event was back at Ground Zero, where hipster hero and blues pianist Mose Allison played a rollicking set. Allison’s keyboard stylings are one of the hidden columns of pop culture—he’s been covered by The Yardbirds and the Clash, memorialized by musicians from Frank Black to Elvis Costello to Keith Richards. In the low-lit space of Ground Zero, Allison wove deft, familiar melodies, producing more sound than seemed possible for his frail frame.

American popular music, the kind Mose has mastered, has always been equal parts sugar and grit. The blues, when it began, was many things—a lament, a series of coded complaints about racial injustice, and a way to blow off steam on a Saturday night—but it was also the music of sinners. You heard it where people came to forget, to drink, to dance and to otherwise make the Southern Baptist preachers shudder. It was dangerous and catchy, sweet and powerful. Long before Elvis’ lower half was censored, before parents bemoaned their children for listening to Kiss, before hip-hop gave us the parental advisory, the blues defined American popular music. In 2010, it no longer does—it has become, despite the efforts of its champions—a museum display. However haunting the melodies and skillful the practitioners, it is a genre that has changed hands, the rough edges have been sanded, the demons autotuned out. The blues that lives in Clarksford have been pickled, preserved in order to be trotted out on demand. Like any popular music, once the makeup of the audience shifts the songs take on a different character. You would be as likely to see Allison in Carnegie Hall as in Clarksdale. That’s the trouble with the search for authenticity, the all-consuming quest for what Greil Marcus called the old, weird America. Like anthropologists who inadvertently destroy a culture by documenting it, we change places like Clarksdale irrevocably when we identify them.

The problem with the juke joints, with the barbecue pits and abandoned warehouses and old-time motels and the whole town, in fact, is that it feels ossified for your benefit—like you’re taking a vacation in an institution. The romance of the past that draws visitors is the same thing that prevents the city from moving forward. The monuments in Clarksdale, like the ones sprinkled all over to the South, are to a different Mississippi, a dangerous, brutal place that managed to produce some of the most innovative and beautiful pop music of the 20th century. The Most Southern Weekend ever is a nod to the authenticity of the old Southern town—the real, down-home, fried-chicken-eating, cotton-pickin’ South—but that South is as much a construction as any Disney theme park. Watching the overwhelmingly white crowds dance to Mose Allison, wriggle at the juke joints, and lap up barbecue sauce, it’s hard not to think of the whole thing as a sort of spirited do-over, a way to go back and rectify the injustice of the past through sheer cultural enthusiasm. It’s a lovely illusion, a grand tall tale—one that Faulkner surely would recognize. But it’s an illusion nonetheless.

]]>

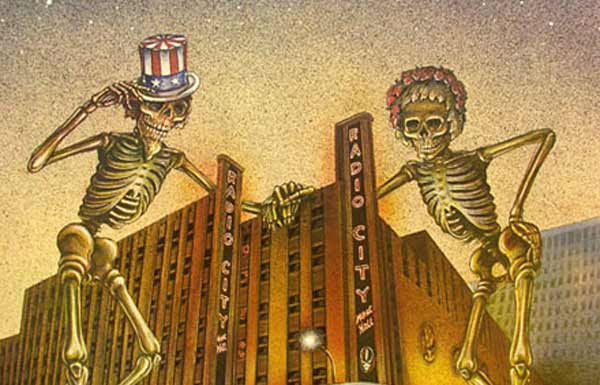

Dennis Larkins and Peter Barsotti, Radio City Music Hall poster Oct. 22-31, 1980. via New York Historical

In 1971, Grateful Dead manager Jon McIntire slipped a notice into copies of the Grateful Dead (Skull & Roses) LP that became the liner note heard ’round the world: “Dead Freaks Unite! Who are you? Where are you? How are you? Send us your name and address and we’ll keep you informed.” Thus was established one of the most prolific and intense bonds between a band and its fan-base in pop music history. Before Justin Bieber became king of the twitterverse and Lady Gaga inspired an academic journal, before the age of Myspace profiles and instant e-mail newsletters, the Grateful Dead established a diverse and loyal group of followers the old-fashioned way, maintaining a rapport through newsletters and a general openness towards their adoring Deadheads. For close to three decades, the Grateful Dead successfully constructed their own subculture, a hallucinogenic-friendly, tie-dyed group with Jerry Garcia as their gentle, bearded leader.

The New York Historical Society initially seems like an odd place to commemorate the achievements of the Grateful Dead, rubbing shoulders with artifacts of the American Revolution and John James Audubon’s watercolors. But browsing through the Society’s exhibit of items from the Grateful Dead Archive at UC Santa Cruz, it begins to make sense. The Dead’s roving entourage included a number of graphic designers, photographers, illustrators, and filmmakers that rode along with the equipment crew, effectively creating a mobile artists commune. And then there’s the fan art: carefully decorated envelopes, jigsaw puzzles, comic book strips featuring Bob Weir. The Grateful Dead may not have invented the fan-band interaction, but they perfected it, and their insights have spread their tendrils throughout popular culture recently reaching as far as the Obama campaign. It’s no accident that the remaining members of the Grateful Dead gathered twice to perform benefits for the president’s 2008 campaign and though he might be less heavy on the psychedelics, many of Obama’s strategies came right out of Phil Lesh’s playbook. (Even Obama’s rising sun campaign logo has some fleeting resemblance to the Dead’s “Steal Your Face” skull—if you stare at it long enough).

Amalie Rothschild, Fillmore East Marquee, December 1969 via New York Historical

The exhibit, which was curated by Bill Kreutzmann and Grateful Dead archivist Nicholas Meriwether, traces the group from their beginnings as Ken Kesey’s house band to their status as rock-roots legends, dotting the path with glass cases full of memorabilia and day-glo t-shirts. There are Alton Kelley and Stanley Mouses’s famous skeleton and roses posters, photographs of the Dead playing at the Columbia University protests in 1968 (They snuck onto campus in a bread delivery truck), and all manner of ticket stubs, backstage passes, platinum records, and gently used instruments once plied by ex-Grateful Dead members. Perhaps the most impressive part of the collection is the arrangement of the life-sized skeleton marionettes used in the music video for “Touch of Grey,” slumped in various poses in front of an enormous American flag.

Part of the Grateful Dead’s aesthetic mission was to make their music as unfiltered and undistorted as possible; the audience should hear the same thing that they heard on stage, free of monitor interference. As they filled bigger and bigger venues, this became what sound engineer Bob Matthews called “The Gig Worm Orouboros.” In one of the sketchbooks on display he writes succinctly: “Dilemma: the threshold for relevance—optimum, psycho-social distance (ambience) with audience.” The solution he and fellow audio engineer Owsley “Bear” Stanley—also famous as an LSD chemist—arrived at was a speaker tower of Babel-like proportions called the “Wall of Sound.” The blueprints present the details of a gargantuan structure, a mad architectural project set up during the band’s 1974 shows before the impracticalities and cost of the thing, which took up to 14 hours to set up and towered 40 feet high, forced it into early retirement.

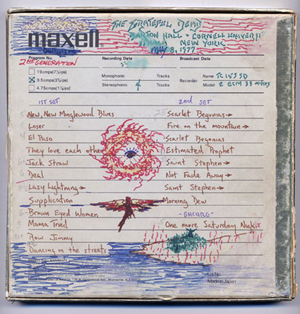

Dick Latvala, 7 Inch Audio tape box, reverse with list from May 8, 1977 show at Barton Hall, Cornell University. via New York Historical

Between the framed riders and guest lists—the Dead apparently required Budweiser, Dr. Pepper and fruit juice at every show, whiletheir honored guests included Bill Murray and Robin Williams –there isn’t much room devoted to the actual music. Throughout the exhibit, speakers at the top of every placard softly play an array of Grateful Dead’s greatest hits, but there’s not much to inspire the sort of fervor displayed all around. Part of this is a practical limitation: In such a small space, it would be difficult to play more than one song at once without becoming an incubator for migraines. But partly, I suspect, it’s because the Grateful Dead phenomenon exists independently of their music. They weren’t hardened showmen like the Rolling Stones or objects of teenage lust like the Beatles. Instead, they carved out a new space between musicians and music-lovers, a forum of mutual exchange. Fans could call up a hotline for Dead news and petition for backstage passes, and even record live performances with the band’s blessing. It’s testament to the band’s dedication to their fans that this exhibit exists, filled with the hand-crafted “Steal Your Face” yarmulkes and lovingly hand-colored illustrations that were sent to and saved by the members of the band. The exhibition, in fact, is as much about Deadheads as about the members themselves—and that is what secures the archives a place in an historical emporium instead of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame or an aging hippie’s basement. The Grateful Dead harnessed the power of the crowd before crowd-sourcing was a verb, and they’re not going to fade from our cultural lexicon anytime soon. Whatever you think of “Box of Rain,” there’s no denying the significance of method that produced it. The Dead, it would seem, are here to stay.

]]>

Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses, via Gotham Gazette

The Battle for Gotham: New York in the Shadow of Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs by Roberta Brandes Gratz. (Nation Books, April 2010)

In 2009, Janette Sadik-Khan, the lithe, stylish Transportation Commissioner of New York City, cut the ribbon on Times Square’s newest makeover. Sadik-Khan, under the direction of Mayor Michael Bloomberg, had closed Broadway to automobile traffic from 42nd to 47th streets, transforming Manhattan’s famed neon temple into a vast pedestrian plaza, sprinkled with metal beach chairs and concrete planters. “Streets are public space,” Sadik-Khan later proclaimed at a lecture at Occidental College, “We want to see streets for the people.” Her detractors accused her of hindering circulation; her supporters hailed her as a visionary, a worthy diplomat in the constant struggle between New Yorkers on foot and those behind the wheel. An article in New York Magazine claimed Sadik-Khan as a luminous compromise between mayoral bureaucracy and neighborhood-level planning, “equal parts Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses.”

For any city planner, architect, advocate, or transportation engineer in New York, a comparison to either Jacobs or Moses is inevitable. The rivalry between Jacobs, an architecture critic and community organizer who fought for an organic approach to neighborhood rehabilitation, and Robert Moses, grand poobah of New York City public works for some 30 years, is the most famous city-planning clash of the 20th century. In New York, both figures’ philosophies are inescapable, inscribed into the very streetscape of the city—no corner park, glass-paneled hotel building, or traffic plan can escape association with either Moses’s large-scale clearance programs or Jacobs’ community-based revitalization efforts. Often, real-estate developers and municipal officials claim pieces of both legacies, citing the grandness of Moses’s ambition and Jacobs subtler, interventionist approach.

To journalist and urban critic Roberta Brandes Gratz, author of The Battle for Gotham: New York in the Shadow of Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs, the idea of mixing Moses’s and Jacobs’s theories is laughable. “Trying to blend Moses and Jacobs is like trying to push together the old black-and-white Scottie dog magnets: the harder you push the more resistance you feel.” The Battle for Gotham mixes Gratz’s personal manifesto against the planning practices and ideological approach of Robert Moses with recollections from her childhood in Greenwich Village, investigations from her reporting days at The New York Post, and accounts of the destruction various Moses projects wrought upon the urban fabric of the city. It’s a confusing hodgepodge, part policy critique and part memoir it’s a litany of complaints as much as it’s an analysis.

In the book, Moses emerges as a kind of urban-studies super-villain, the tyrannical, automobile-friendly Goliath to Jacobs’ pedestrian-defending David. This is Disney movie stuff: the scrappy, bespectacled community advocate versus the big-government, cigar-chomping transportation boss. His policies are to blame for the city’s decline into near-bankruptcy; his eventual defeat by bands of Jacobs-inspired grassroots planners the reason for New York’s revival since the 1970s. Gratz’s loyalty to Jacobs is unwavering, her depictions of Moses scathing and resolute:

No matter that in his early good government career Moses was a legitimate reformer, no matter how noble one thinks Moses was because he amassed only unbridled power and not bags of money for himself, no matter how wonderful one might judge Moses’s parks, he was probably the most undemocratic, arrogant, ruthless, and racist unelected government official of the twentieth century.

Gratz’s position isn’t an unusual one: Moses’s reputation has long been in shreds, and Jacobs’s theories championed as a panacea for any number of urban woes, from racial clashes to the MTA’s budget deficit.

It’s an attractive dichotomy, and Moses makes a good target. Doubtless, Moses’s idea of the city as a nexus of cloverleafs and expressways clashes with the sustainable, foot traffic-friendly version favored today. Certainly, Moses’s slum-clearance projects displaced hundreds of families and businesses and hastened the decline of working-class neighborhoods, partitioning the metropolis instead of knitting it together. Without question, New York would be a very different place if not for Jacobs’s impassioned activism against the Lower Manhattan Expressway, originally slated to demolish SoHo. But to lay the blame squarely at Moses’s feet for everything from the new Yankee Stadium to Atlantic Yards is too easy; it denies the very richness and complexities of the urban fabric celebrated so memorably by Jacobs. To treat Moses as a straw man and Jacobs as a saint ignores the national, economic, and societal forces that shape the city just as surely as city planners and neighborhood organizations.

Gentrification is the unacknowledged elephant stomping through Battle for Gotham, the consequence of the influx of upper-middle-income families back into the refurbished city. Gratz extols the virtues of Greenwich Village and SoHo, but has little sympathy for the small businesses and lower-income residents forced out by the influx of upscale retailers. “Whatever and whoever have left exist elsewhere,” she writes, “Some of the very people leaving SoHo and moving elsewhere are helping the process take hold in emerging SoHo-type districts in other cities.”

It’s a remarkably tone-deaf position, one that gives little consideration to the class segregation that occurs in cities like New York. The displacement of long-time residents in Bushwick and Harlem may result from rising rents rather than demolishing wide swaths of the city, but it is displacement nonetheless, and an equal threat to the mixed-income communities Jacobs celebrated in her Death and Life of Great American Cities. The structural and economic dilemmas New York City faces never came from just one man; the historical forces shaping the city came into play long before Moses signed on as Parks Commissioner. Nor did Jacobs, for all her astute observations about community conservation, have all the solutions for an ever-evolving metropolis. Both figures loom large over the city, but they cast only shadows. The victories—and failures—of New York can’t be attributed to either of them alone. They belong to all of us.

]]>