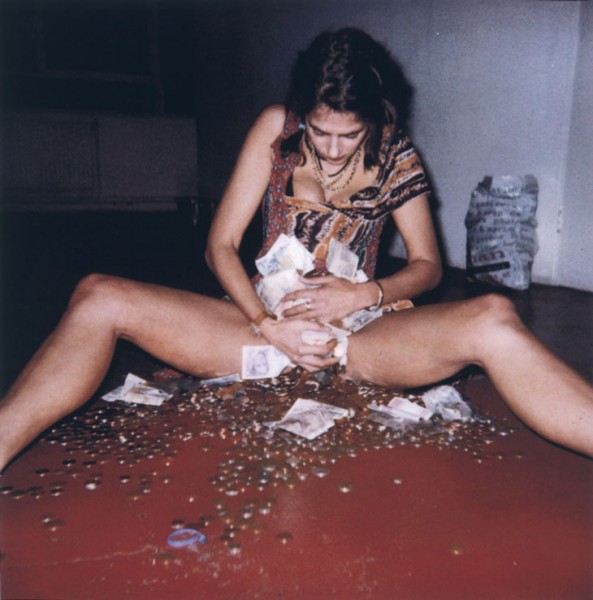

I've Got It All, 2000 © Tracey Emin via Saatchi Gallery

In her photographic self-portrait entitled I’ve Got It All (2000), Tracey Emin faces the camera with head bowed and legs splayed. Wearing a Vivienne Westwood dress and her signature gold necklace, she cradles an armload of banknotes and coins at her crotch. It’s a delightfully ambiguous gesture. Is she suggesting an appropriation of an exterior material economy into a physical interior in attempting to incorporate the money into her own body, or has she become a human slot machine, transformed into a progenitor of pure liquid capital? At the time I’ve Got It All was created, Emin was already a well-known media figure enjoying both commercial and social success, having stirred controversy by exhibiting her work My Bed in the Turner Prize nominee exhibition the previous year. Here, in her self-portrait, she celebrates the phenomenon of her success with tinges of both emotional poignancy and sarcasm. The presentation asks us to join her in celebrating such prosperity, while the tone of her depiction invites us to question both its nature and its value.

It is around these questions that the exhibition Tracey Emin: Love Is What You Want, which ended August 29th at the Hayward Gallery in London’s Southbank Centre, performs its discursive seduction. At its best, the show functions as a catalyst, propelling us into the dynamic and highly emotional world of the artist herself. Emin’s work, often frantic, sexual, abject, and contemplative — explores themes of love, grief, isolation, and longing, examined through the medium of an intimate biographical narrative. Emin is deeply, even chiefly, concerned with intimacy, both our reactions to it, and our attempts to move beyond it. Tracing her personalized engagement makes for a mesmerizing show, equal parts fascination and terror.

The show represents the most important retrospective of the artist to date, and its content gazes simultaneously backwards and forwards. This being a mid-career occasion, the past work is thoroughly surveyed, and is here arranged according to media, which also falls into a loose chronological correspondence. The most recent work fills a large second-floor room, while a series of sculptures created specifically for the exhibition occupy the rooftop courtyard. Natural light spills onto the upper floors of the gallery, where the more recent work offers a welcome sense of calm after the emotional hurricane housed on the windowless ground floors.

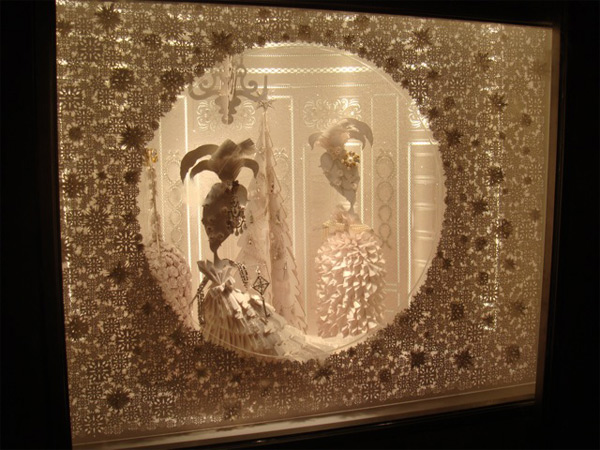

Hotel International, 1993 © Tracey Emin via Southbank Centre

We are greeted by a selection of Emin’s eponymous quilt pieces. Created using fragments of clothing from her own childhood or from the closets of family and friends, these hand-appliquéd blankets spell out textual messages that reference moments of biography or serve as expressive slogans. The first of these pieces, Hotel International, completed in 1993, states birthday details, names of family members, and places Emin lived during her childhood. Longer textual narratives are also included. Handwritten in tiny script lettering, these pieces invite the viewer to step closer to engage in detailed reading. The appliquéd words “KFC Margate”, a reference to the location of a flat Emin shared for several years with her mother and grandmother, are supplemented by a paragraph of hand-written text detailing personal memories from this period of her life.The various colors, sizes, and styles of lettering, reminiscent of banners used for political or religious purposes, further pays homage to both the tradition of second-wave feminist art, and, by extension, the traditional craft-based practice from which such work took its form and inspiration.

Sometimes the work crackles with mischievous wit, as we encounter in her neon sculpture Is Anal Sex Legal? (1998). Rendered in vivid purple, the sculpture reads simply “Is anal sex legal? Is legal sex anal?” Elsewhere, she performs with a more uplifting flair. In the 1995 video Why I never became a dancer, the artist narrates a story from her teenage years about her use of sexual behavior as a means of escape from the drudgery of her hometown. Scenes of Margate are depicted as visual points of reference underscoring Emin’s confession. After we hear of a dance contest in which she is forced offstage by a heckling group of local boys, she lists them each by name, telling them “This one’s for you”, before we see her dancing to Sylvester’s “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)” with an exuberant smile splashed across her face. Through reenacting the performance for which she was ridiculed, the artist revisits a painful memory while whimsically rehearsing an alternate variation of its outcome.

Many pieces included in the show, however, explore darker themes. A 2008 painting entitled Black Cat takes inspiration from Poe’s 1843 short story of the same title, examining guilt and madness. Rendered with dynamic strokes that literally drip from the canvas, the painting depicts a large, partially nude figure positioned in the center of the composition. The figure’s face is obscured in a swath of black, while its hand masturbates above a deep-red pool of blood positioned at its feet.

Knowing My Enemy, 2002 © Tracey Emin Photo: Stephen White via Southbank Centre

Emin’s most recent work comprises the final segment of the exhibition. Color has here been drained from the objects, and biographical narrative further stripped away, allowing material and emotional content to move into the foreground. Salem (2005), constructed as a large timber sculpture arranged around a vertically positioned white neon tube light, evokes images of witch-burning, and the surrounding fear and sexuality. It Always Hurts (2005) finds Emin revisiting her earlier blanket forms, but with more explicit visual imagery. Created with embroidery and appliqué in delicate shades of cream, beige, and white, the piece depicts a central image of an embroidered nude bending provocatively away from the viewer under the headline, “Be with who ever it always hurts.” Upon moving closer, we discover tiny images of truncated torsos, a recurring image found throughout the scope of her work, nestled between small handwritten notes that read as whispers. “Nothing else but me,” one declares. It is a message as direct in its delivery as it is devoid of self-pity. By asking us to temporarily suspend our analytic impulses, she encourages a wider array of responses, and her work becomes both playful and haunting.

A broader inquiry into British art is at stake in the staging of this particular mid-career retrospective, one readily illustrated in its choice of hero image: a 2011 photograph of Emin running along a cobblestone street and away from the camera, her nude legs and torso exposed beneath the flapping union jack she waves behind her. As a headliner of the Southbank Centre’s four-month Festival of Britain, the 60th anniversary celebration of an annual festival that showcases “British culture and creativity”, the show seems to further position its content as representative of contemporary British culture.

Running Naked, 2000/11 © Tracey Emin via Wallpaper

Emin, of course, emerged as an affiliate of the Young British Artists, who were recognized as much for their unconventional practices as for their impassioned energy. Beginning in the late 1980s, they had started exhibiting in abandoned urban spaces across the southern and eastern areas of London. Emin exhibited her first solo show in 1993 at Jay Jopling’s White Cube Gallery. Meanwhile, as the world economy began to prosper, London began to experience a period of urban renewal. Cultural innovation began to parallel such development, and many see the story of the YBAs — the narrative of humble beginnings followed by a swift rise to success and subsequent periods of debauched excess, as an apt metaphor for the prosperity of the nineties themselves. As Patricia Ellis observes,

It’s nice to think of the YBAs as the art world answer to the dot-com whiz-kids- geniuses in their fields with insurmountable imagination and vision, nonconformists, reinventing the terms on which business is done.1

If the art of the YBAs served in the 1990s as the British cultural echo to the dot-com boom, as Ellis suggests, then we might expect Emin’s current work to have been tempered as much by a more sober economic climate as by the maturity that comes with experience. However, although the work has distilled into a distinctly middle-aged minimalist expressionism, we find its content more spirited than ever. By inviting us to step uncomfortably close, Emin continues to question the nature of intimacy, and to explore the limits of the boundary between self and other.

Although the effects of her work still resonate strongly, the shocked reaction that accompanied its debut has subsided. If the demographic when I visited is any indication, the British public now deems Emin appropriate for children under ten. Perhaps it was lingering American puritanism, as it seemed I was the only one uncomfortable when several children under the age of five were left to wander alone through What it feels like (1996), a video installation in which Emin recounts her first abortion in vivid detail. But perhaps this means her work has succeeded?

The exhibition includes an early work, Emin’s Army (1993-1997), which consists of a group of miniature cardboard tanks placed strategically across a world map that lies horizontally on a table. Flags bearing the hand-written names of Emin’s friends are planted triumphantly around the world. “S. Lucas” conquers New Zealand, while “G. Hume” takes upstate New York and “D. Hirst” dominates Hong Kong. The setup, cheerfully reminiscent of a board game, pursues a focused agenda beneath its whimsical tone. Emin asserts her community’s authority over an established market system with exuberance, her victory no less delightful for having long since been assured.

- Ellis, Patricia. 100: The Work That Changed British Art, ed. Charles Saatchi (London: Jonathan Cape and The Saatchi Gallery, 2003), 201.

Tim Thyzel, Wheelies (detail), 2004 via BRIC Arts

What happens when we confront certain unavoidable aspects of history? How does our relationship to the past impact the way we negotiate the complexities of trans-cultural identity? Two shows at BRIC Arts Media search for reconciliation among the shifting landscapes of compromise and cultural dislocation.

As Aaron Lazare asserts in his book On Apology, “Remorse must accompany an apology as a sign of its authenticity.” A further show of humility is also essential, and shame is an appropriate complement to remorse. To apologize, therefore, is to directly confront our fallibility, to humbly admit the existence of our humanity. The work presented in Apologies and Further Concessions investigates the ways in which individuals and institutions respond when forced into a confrontation with their own inadequate past.

Institutional and individual concessions alike juxtapose to create a playful, if rather melancholic, rhythm throughout the show. Tim Thyzel’s Wheelies, a group of cast concrete blocks placed on inept wheel appendages, recasts the familiar form of wheeled handcarts used by transient urbanites. Thyzel expands the reference to assert the ultimate impotence of our individual modes of adaptation. Lying derelict upon the gallery floor, the objects elicit our sympathy while playing out a dark satire of the unique awkwardness such futility engenders.

Jennifer Grimyser, Change is Now (photo of performance), 2007 via BRIC Arts

Other pieces apprehend impossibility in a slightly different way. Jennifer Grimyser’s Change is Now chronicles the artist’s performance at a Chicago gallery in 2007, wherein she wrote the title phrase on a wall, crossing out the last word and rewriting it at five-minute intervals. After three hours, her work clearly documented the limits of her language suspended against the movement of time.

A book project by Melissa Dubbin and Aaron S. Davidson uses a form of natural disaster — earthquakes — to inquire after the status of knowledge amidst the tenuousness of human institutions. Fallen Books gathers photographs taken from various libraries in the moments after an earthquake has toppled the bookshelves. Assembled chronologically with documentation of place, time, and local media coverage, the collection becomes both an archive of these seismic events and an active participant within the depicted systems. A certain beauty appears within the disorder as we are reminded of the formerly material nature of the archive. The scattered, multicolored volumes mime the fragility of our organizational systems.

Other work takes on the complications proper to government-issued apologies. Hong-An Truong’s (who, full disclosure, writes for this magazine) video installation A Measure of Remorse engages the complexities associated with Japan’s official 2005 apology to China for its aggression during World War II. Composed of gently floating images of a Chinese novelist, the Japanese ambassador to the US, and an American journalist, by turns sitting quietly alone and embracing in slow duets, set to a subtle score of news clips surrounding the event, the piece becomes a powerful landscape, complicating our assumptions. Going beyond official apologies A Measure of Remorse offers a subtle suggestion of how we might bring the complex relationships between apology, forgiveness, and reconciliation into better focus.

Melissa Dubbin & Aaron S. Davidson Fallen Books (detail), 2008, via BRIC Arts

By turns sardonic, poignant, and quietly melancholic, the pieces in Apologies and Further Concessions create a lyric rhythm that explores the surface of these reactions without ever cutting too deep. The result is a vague tension that never quite resolves itself. But this is the point. To the extent that apologies are at once an admission of guilt and the beginning, perhaps, of a concerted attempt at remedying injury, they necessarily remain unresolved, extending far into the future.

A Wild Gander, curated by Baseera Khan, presents the work of five New York-based artists affiliated with the South Asian Women’s Creative Collective. The show’s theme takes inspiration from Joseph Campbell’s collection of essays entitled The Flight of the Wild Gander, wherein he describes the Sanskrit concept of the para mahamsa, a spiritual teacher who is able to transcend earthly banality much the way that geese are able to transcend gravity through flight. The work of the artists presented here explores the liminal spaces created by migration, digital communication, and inter-cultural identity, negotiating them in an effort to create trans-local dialogues.

An ironic text-based installation by Divya Mehra drolly asks after the show’s relationship to identity, scrawled vertically across the gallery floor and wall, it reads, “I’m Indian, so I’m in this Show.” A video installation by Mehra, situated nearby, is composed of a pile of 27 televisions that simultaneously play a loop of the artist in performance. Directly addressing the camera, Mehra asserts one phrase delivered in multiple styles: “I am a lot like Bruce Nauman.” The satiric performance, repeated throughout the 27 video channels, results in a cacophony of sound and image that foregrounds Western art historical influence while simultaneously rejecting, through parody, the appropriation of its instinct towards domination.

Chitra Ganesh, Ghostwriter, 2009. via BRIC Arts

Some work reacts to commonly exported depictions of South Asian culture. Chitra Ganesh plays with lenticular photography to subvert traditional notions of Indian femininity in two photographic installations. Here, the artist disfigures the face of a Bollywood heroine to produce continuously shifting images that gently mar a culture’s historic expectations of beauty.

Jesal Kapadia’s series of prints entitled Ditto, or “the same as what has been said” pairs iconic works by Western male artists with found images of similarly shaped South Asian industrial structures. The form of Buckminster Fuller’s concept for his Geodesic Dome City is compared to a row of large kilns, while the shape of Smithson’s Spiral Jetty is echoed in the form of a spinning industrial machine. The juxtaposition of these images here snickers at the presence of an apparently universal aesthetic sensibility that lithely transcends geographic and cultural boundaries.

Jesal Kapadia, Telegraph, 2005/10. Digital video. via BRIC Arts

Overall, the artists here adroitly navigate their various cultural and aesthetic influences to celebrate local dialogues within a broader landscape of cross-cultural discourse. Many go further, asserting the efficiency of these investigations taken on their own terms. The resulting work feels both inquisitive and self-assured.

Presented together, the shows offer several, subtle examinations of how we come to terms with ourselves within a large confrontation with established systems of social interaction and cultural representation. In both cases, the supplementary literature accompanying the exhibition proves to be a bit too explicit. This results in a presentation that feels slightly too conceptually controlled, leaving little room for playful interpretation. Yet given the focused scope of the subject matter, such precision can be appreciated, to the extent that it allows for the illumination of such intimate mediations.

Apologies and Further Concessions, curated by Erin Sickler, and A Wild Gander, curated by Beseera Khan, were presented at BRIC Arts Media from March 25- May 1, 2010.

]]>

Dragos Bucur in Police, Adjective; Marius Panduru via Interview

Corneliu Porumboiu’s latest film, Politist, adj (Police, Adjective), now playing at the IFC Center, explores the ways in which language operates as a source of authority via the narrative of an individual conscience set against a small-town Romanian bureaucracy. Set amidst a decaying post-Soviet urban landscape, the story follows a young police detective named Cristi who is assigned to investigate a group of teenagers suspected of using hashish. Caught between his professional obligation to uphold the law and his moral reluctance to mar the record of a vaguely wayward youth, we watch Cristi negotiate his personal beliefs within the context of an oppressive and didactic system of law enforcement .

We accompany the detective, thoughtfully portrayed by Dragos Bucur, over two days as he trails his main suspect, attempting to build sufficient evidence in his defense and avoiding a sting operation that would land the youth in jail. His reluctance towards the law in question isolates him from his colleagues and quickly establishes him as an outsider. Unable to orchestrate a sting operation with a free conscience, he avoids reporting to his captain and withdraws from his fellow employees. Several times, he expresses his belief that Romanian drug laws will change in a few years, citing his observations of such relaxed attitudes in the Czech Republic, where citizens are allowed to smoke in the streets. This international perspective, coupled with a strong fidelity to his own values, puts him in ideological opposition to his native government. It is a familiar conundrum, but one that resounds here with poignancy and wit.

Marked by long passages that show Cristi walking, eating, smoking, and waiting while he carries out his assignment, Porumboiu’s filmmaking celebrates the quotidian while simultaneously isolating his subject within the psychology of his increasing solitude. In a particularly compelling and hilarious moment, we see him eating dinner alone in the kitchen of his apartment while his wife plays a popular love song from the other room. It blares loudly into the kitchen (his pleas for her to turn the music down remain unheeded) as he shovels food into his mouth in a gesture of desperate self-preservation. The use of diagetic sound as the sole accompaniment anchors us in the details of the Cris’ everyday existence and he quickly garners our empathy.

The extended cinematic description is juxtaposed with dialogue that examines the nature of language itself, and it is here that we see the film’s central theme emerge. In a final confrontation between Cristi and his boss, the formidable police captain Anghelache, the latter condescendingly doles out a lesson in semantics. After explaining that it is ultimately his conscience that prevents him from arresting the teenagers, Cristi is instructed to offer his definition of this word. His reply, “Conscience is something within me that prevents me from doing something bad that I’d afterwards regret,” is compared with the definition found in a Romanian dictionary, from which Cristi is forced to read. Further definitions are read aloud: law, moral, police. The scene is shot in a single long take, with several smaller cuts added for narrative continuity. Its sardonic, deadpan humor rings with situational irony, and it becomes hard not to laugh at the ridiculousness of the scenario.

Beneath the scene’s cutting irony lies a subtle investigation of language’s relationship to power. Here, law enforcement’s strict adherence to the letter of the law rehearses the reliance of authority on language as a source of power. We see power derived directly from linguistic definition, delimiting itself according to the dictionary’s prescriptive code. Accordingly, each police officer must be the definition of a law enforcement official, and each offense of the law must be treated precisely as such. If language can here be read as an allegory of state power, then the act of definition performs as a metaphor for the law, delineating rules about how this society uses words much the way that laws demarcate boundaries of human behavior.

Porumboiu here suggests that the state’s obsession with semantics is symptomatic of the impoverishment of its ruling ideology. To the extent that this semantic rigidity permeates every level of legal offense, the system is revealed as vulnerable, even broken, and the film subsequently begins to emerge as an examination of such endemic disability. Crumbling urban infrastructure frames Cristi as we follow him throughout his day. Graffiti litters decaying concrete walls and deep potholes speckle the roads. Even the technology within the government offices seems on the verge of collapse. A mammoth-sized computer sits unused next to Cristi as we watch him hand-write his police reports. The dispassionate attitudes of his fellow government workers, who seem vaguely disinclined to help him execute background checks that could potentially exonerate his suspects, similarly illuminate such dysfunction. Caught within the mechanics of a dilapidated system, they have become too preoccupied with meeting friends for coffee or performing their own rote administrative functions to be fully effective.

The form and subject matter of Police, Adjective arguably recalls Bruno Dumont’s 1999 film L’Humanité, wherein a police detective’s investigation of a horrific crime consequently illuminates his struggle with the limits of human understanding. Set in a small village in Northern France, the film similarly employs long shots and relies exclusively on diagetic sound to explore a psyche perched on the verge of disillusion. Porumboiu’s film departs from Dumont’s, however, in its overall lightness of tone. Beneath the strict formal surface of Police, Adjective lies a sardonic playfulness that makes it extermely enjoyable to watch. It is to this extent that the film can be read as a deadpan parody of the traditional police genre, as its self-referential title indicates. Porumboiu seems to suggest that irony’s subtle fluidity can perform as a counter-discourse, and he constructs the film’s tone as a vehicle for such delicate subversion. Ultimately, Porumboiu offers us a darkly humorous look at the relationship between linguistic and political structures, one that cuts to the core of how we operate as individuals within these shifting, dominant systems. Presented with such complicated negotiations, we can certainly hope to find solace in the nuance of irony, as Porumboiu suggests.

]]>

Heiner Goebbels, Stifters Dinge, photo: Stephanie Berger for Lincoln Center

The work of Adalbert Stifter, the 19th-century Austrian novelist, has been the subject of a polarizing critical debate since its earliest publications. Marked by long and detailed descriptions of characters’ environs, his work is often criticized for being tedious and overly mannered. Yet there seems to be a deliberate rhythm to his method; by forcing the reader to slow down and contemplate objects and landscape around his characters, he reveals something unique about the way humans relate to their various surroundings.

Heiner Goebbels takes such inspiration from Stifter’s texts to create Stifter’s Dinge, a mechanized installation presented last month at the Park Avenue Armory as part of Lincoln Center’s Great Performers Season. Offering a multimedia performance work that takes the writer’s affinity for objects and landscape as a point of departure, Goebbels investigates to what extent humans can control ecological forces and negotiate an uncertain future.

The work is presented as a self-contained multimedia installation that incorporates sound, video, and moving visual elements to create a tableau synthesizing these disparate forms. Were it not for the absence of actors, the piece would undoubtedly read as a modern formulation of a 19th-century Gesamtkunstwerk. Instead, it is precisely this absence that Goebbels explores. By foregrounding elements that usually serve to underscore or illustrate main action within a traditional theatrical setting – lighting, sound, fog, projection – the artist focuses audience attention on detail, asking us to slow our sensory perception to examine objects as signifiers of human presence.

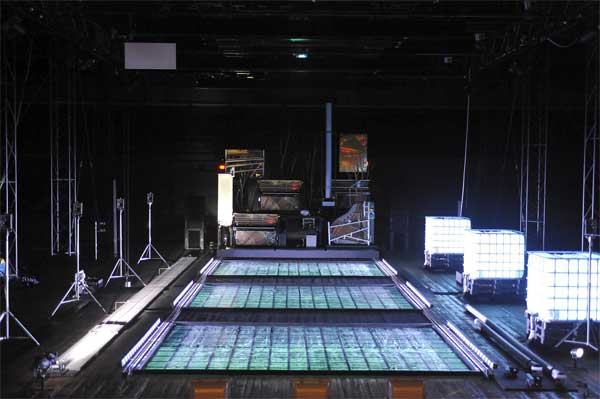

Heiner Goebbels, Stifters Dinge, photo: Mario Del Curto for Lincoln Center

The installation is centered on a group of five pianos whose cabinets have been stripped away to expose their inner workings. Sound is produced by mechanical manipulation of the instruments in several ways; the automatic movement of keys on some resembles traditional player pianos, while the strings of others are plucked directly with a mechanical arm. One instrument consists solely of a grand piano’s soundboard, plate, and bass strings, which is tilted vertically and played with a device that strums along the length of the strings. Here, the copper coils that wrap around the steel core of the string are physically articulated, resulting in a low ratcheting sound that adds a distinct tension to the music.

The pianos are arranged on a moving platform among several flat metal sheets, which are also mechanically manipulated to produce sound. Pipes, speakers, and audio equipment are added to the stage, and tree branches are tucked between instruments. Taken together, these elements become a single entity that functions as the visual protagonist of the work, producing most of the live sound and acting as a backdrop for the video projection. Its movement within the environment scores the piece’s visual rhythm; it moves, by turns, downstage and back until finally arriving at the foot of the space in a grand climatic gesture.

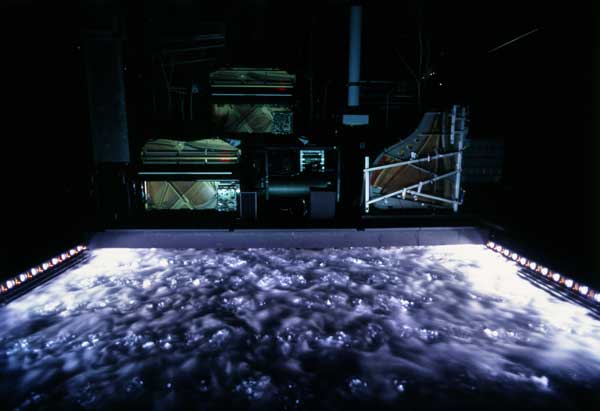

The platform is situated behind three large troughs, which are sprinkled with dry ice at the beginning of the piece. Water from three adjacent tanks is siphoned into the troughs, causing the ice to bubble and create a mystic, foggy atmosphere that evokes the restive subtext of Stifter’s phrasing. Speakers are placed alongside the troughs, as well as various other sound-producing elements, including industrial pipes that bellow when struck upon their open ends, and a stone that produces a grating noise when mechanically dragged along a longer length of rock.

If the entire piece can be viewed as something of a multi-sensory symphony, then these physical elements play an supporting role to the overarching melodic line created by recorded songs, spoken text, and projected video that carry the narrative forward. A mélange of international sources is evoked to create a distinctive collage that explores the human response to both nature and to humanity’s own, historically dominant power structures.

Heiner Goebbels, Stifters Dinge, photo: Stephanie Berger for Lincoln Center

Early 20th-century recordings of indigenous songs from Papua New Guinea, Greece, and Colombia are played over lit speakers. A movement from Bach’s Italian Concerto in F Major is performed with surprising subtlety by the player pianos. In an excerpt from a 1988 radio interview, a contemplative Claude Levi-Strauss describes his own solitary nature and intimates a loss of faith in humankind. We hear William S. Burroughs denounce free-market capitalism, and Malcolm X reject the dominance of Eurocentric ideas to assert the emergence of a new value system.

A recording of Stifter’s short story “The Ice Tale” is played over a speaker while a van Ruisdael landscape, Swamp, of 1660, is projected onto an upstage screen. Here, Goebbels creates a potent visual and aural environment that directs appreciation towards both the form and the content of the spoken text. Meanwhile, the color tone of the landscape is slowly modulated from vibrant green to dark sepia in a slow loop that rehearses the passage of time upon objects. Stifter’s text describes a first-person narrative account of a journey through a winter landscape, wherein the characters become awestruck upon hearing, and later seeing, ice falling from the trees around them. The exhaustive detail with which natural elements are described invites the listener to slow her attention and contemplate the drama in the description. A slow plucking of piano strings accompanies the recorded text and further heightens the ominous nature of the scene.

By juxtaposing these various elements of sound and image from across a cultural and historical landscape, Goebbels aims at constructing a broadened, alternative viewpoint from which to consider our relationship to nature. In his program note, the composer states that the work takes Stifter’s texts as a “confrontation with the unknown and the forces that man does not master, as a plea for the readiness to adopt other criteria and judgements than our own and even as an opportunity to come to terms with unfamiliar cultural references.” Goebbels references certainly present us with a diverse international perspective that explores human history’s grappling with itself, represented through a metaphor of struggle with the unknown wilderness. However, to the extent that the work attempts to reference the “unfamiliar cultures”, well-intentioned though this goal may be, it places itself on a rather more slippery slope, insofar as that concept has become somewhat more loaded in the contemporary moment.

Ultimately, the work offers a striking interpretation of Stifter’s language that is at once visually stunning and aurally provocative. The title of the work, Stifter’s Dinge, translates to “Stifter’s things”, and it is precisely Stifter’s fondness for the objects he describes that Goebbels explores. By limiting human presence within the piece and focusing on atmospheric elements, the artist celebrates both natural and man-made material. These effectively become signifiers of human presence, simultaneously reminding us of our collective achievements – and our shortcomings – within the presence of larger natural forces. Considered this way, the work becomes a celebration that continues to linger long after the sound of the piano strings’ final plucking has died away.

Stifter’s Dinge (2007), composed and conceived by Heiner Goebbels, was presented by Lincoln Center on December 16-20 at the Park Avenue Armory as part of the Great Performers Season.

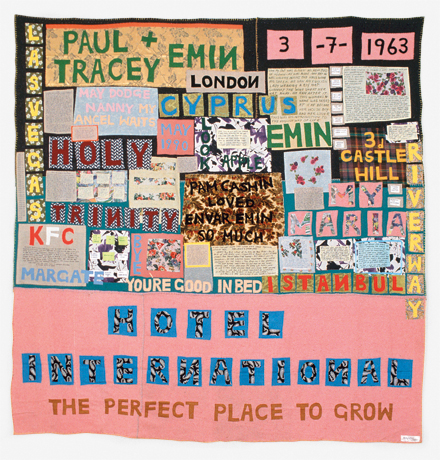

Bloomingdales Shoe Department

Nowhere does the spectacle of holiday consumption offer a more visually compelling performance than in the window displays of Midtown’s luxury department stores. Each year, these flagships deck their windows with ornate displays that feature promoted items set against props and backdrops, creating miniature installations that perform as public spectacles designed to delight, amuse, and entice.

A close viewing of such displays often reveals carefully composed presentations that celebrate a heightened level of craft. Frequently taking color as a point of departure, the best displays explore juxtapositions of shape, texture, and material presented within a dynamically staged narrative composition celebrating featured objects (i.e. clothing, jewelry, or home goods). By distilling narrative elements and focusing on formal qualities, the displays obtain a level of abstraction that keeps the message light while encouraging the viewer’s imagination to roam freely within the presented fantasia. We feel as if we are peering into ornate jewel boxes, magical realms, or simply worlds of obscene luxury which the average spectator can glimpse but never quite grasp. While there is no art in these displays, there is a logic – a sort of kitschy rhythm – to these shock and awe spectacles of contemporary consumption.

Glitter emerges as the central theme at Bloomingdale’s, whose windows sparkle in multiple colors. One features two large, heavily bedazzled bears reading to a baby, while smaller bears dance around a rotating, multi-tiered display laden with fabricated, oversized gummy bears. A caption on the glass titles the piece and provides whimsical food for thought: “Colorific/Holiday cheer changes a world of black and white/To one filled with all things brilliant and bright”. Indeed. The viewer wishes she had brought her sunglasses.

Another window proves more interactive. Titled “Smile-O-Matic”, this display features smiling lips that float around a giant central mirror. By stepping onto a spot marked on the sidewalk, the viewer can insert her image directly into the installation. From this position, the spectator’s image is reflected along the bottom half of the mirror while simultaneously being recorded and displayed along its upper half.. By inviting the viewer’s likeness into the center of the installation, the display rehearses the evolution of commodity into image.

Installations at other stores take a more understated approach. A few blocks down Fifth Avenue, the windows at Tiffany’s glow with intricately crafted white paper cutouts. The tiny displays evoke the whimsy of animated music boxes and the delicacy of Victorian paper doilies. A delicate proscenium frames a seventeenth-century court salon scene that features turning figurines draped in various diamond accessories. The presence of a glittering key that dangles from the hand of a downstage figure foregrounds the sense of privilege the viewer feels upon gazing into this private scene.

Meanwhile, outrageous displays reign at Henri Bendel, the luxury purveyor of makeup and women’s accessories. In the main window, various modes of consumption are depicted with erotic undertones. Female mannequins don sparkling body suits and harlequin masks to perform a bacchanal scene that celebrates an orgiastic vision of consumption. One mannequin answers the door to find another laden with Henri Bendel gift boxes, while a third sits hunched over a laptop beneath a table dripping with fruit. Another swings from the chandelier, pouring champagne into a tower of glasses that overflows with froth. By thematically linking the consumption of luxury material with food and sex, the display solicits our physical instincts, recasting the act of shopping as naturally pleasurable behavior.

No holiday spectacle-viewing would be complete without a trip to Bergdorf Goodman, the uncontested champion of such holiday displays. Taking Wes Anderson’s recent Fantastic Mr. Fox as inspiration, the men’s installations feature original sets and puppets from the film, adorned with various ensembles that complement its quirk-prep aesthetic. The character Mole is presented in his underground dispatch among bowties that cascade down the side of his desk. Boggis, Bunce, and Bean, the film’s antagonistic human characters, stand under a carved-out section of hillside while pointed Oxford shoes traipse overhead. Here, the miniature set is juxtaposed against human-sized accessories, encouraging a step closer to contemplate the exquisite craft of shoe and set alike.

Across the street, the women’s department riffs on various recognizable scenes from Alice in Wonderland to create a larger series titled “Compendium of Curiosities.” Here again we find a celebratory emphasis on the heightened craftsmanship of designer clothing and decorative art. The Queen of Hearts is evoked in a massive display that depicts three mannequins dressed in Alexander McQueen regalia, playing cards in and amongst an opulently propped environment that features over-sized chess pieces, backgammon boards, and card towers. Here, the entire set is tilted vertically, flattening the scene to create an intricate surface pattern that allows us to survey its layout as we would a game board.

A looking-glass theme marks one of the more dazzling installations. A cut-glass proscenium frames the window as reference to an 18th century Venetian mirror. Versions of such Murano-glass mirrors are prominently displayed atop mirrored Art Deco furniture. Wearing a dress of silver lamé, a mannequin stands on a mirrored console table and gazes into a large hall mirror. Her image is reflected not only in the mirror itself but throughout the installation, whose sleek surfaces bounce light and image within the piece to create a self-referential landscape that confuses our perspective while attracting our eye with its striking aesthetic.

These miniature spectacles offer a carnivalesque appeal, drawing us in with bright lights and shiny objects. The overall effect is delightful but also disorienting. The French term for window-shopping, lèche-vitrines, translates to “window-licking.” And sure enough, the act of touring such displays seems to overflow the typical confines of visuality into some strangely evacuated gastronomical experience; the viewer is left with the feeling of having gorged on too much eye candy.

This fantasy aesthetic of glitter and decadence feels uncomfortably familiar. One wonders if we haven’t become so accustomed to work re-appropriating this particular ultrakitsch style (as in Koons, say, or Murakami) that we forget when we are viewing the real thing. If this is the case, then we have Debord’s image transition performed twice: first in the traditional sense, with commodity becoming image -which Bloomingdale’s reenacted so efficiently – and then a second time as the seemingly ubiquitous artistic parody of this process evaporates, itself, into image.

Each of these moments gestures at a common backdrop, gently exposing a certain ambient pastiche of kitsch spanning the distance from the museum to the retail hub. In the latter, holiday displays perform as spectacular representations of wealth that entice the individual consumer. The former, on the other hand, ostensibly offers a critical community that arrives to appreciate the power and complexity of remixed consumerist tropes. It is interesting to note, then, the extent to which it is the window displays that serve as a social lubricant for passersby to engage collectively. Impromptu social spaces spring up as crowds gather around different installations. People stop to gawk, take pictures, and offer commentary upon the spectacle. Celebratory cigars are smoked and holiday pleasantries are exchanged among strangers. For tourists and locals alike, viewing these windows becomes an opportunity to play out fantasies of wealth, which, in practice, conjure a close approximation of holiday cheer. Here we perform the New York Christmas of our imaginations by strolling down Fifth Avenue to contemplate luxury goods we can certainly see but rarely afford.

The performance of these holiday rituals serves to mask the reality of social stratification by posing as a class equalizer. By taking on the role of public art, these displays offer mass appeal while ultimately catering to an élite few. Pausing to take a peek at these displays is both to experience a playful holiday fantasy and to participate in a carefully orchestrated worship of luxury goods. But this is not so rare, or new, and by now we are accustomed to taking our fantasy with a healthy grain of salt. Perhaps this training is what allows us to find such rituals both pleasurable and heart-warming, even with the lingering stomachache that comes from too many holiday sweets.

All photography taken by the author.

]]>

Emma Hart and Benedict Drew, Untitled Performance, 2009 photo: Marten Elder via Light Industry

There is experimental film and then there is experimenting with the mechanics of filmmaking itself. In the hands of Emma Hart and Benedict Drew, a collaborative London-based duo, film operates as both medium and subject. The artists sculpt provocative multi-dimensional performances that delight while destabilizing our established notions of the genre.

Last Tuesday, Hart and Drew presented three works from an ongoing series of untitled performances at Light Industry in association with Performa 09. Taking the formal deconstruction of the moving image as a point of departure, the duo re-appropriates the medium to create a triptych of performance installation aimed at constructing new ways of looking at the form.

Emma Hart and Benedict Drew, Untitled 6, 2009, photo: Marten Elder via Light Industry

The first piece presented within the series, Untitled 6, explores the extent to which film can act as a physical agent within its own process of production. A bevy of vibrantly-colored balloons float in front of a projection screen. Each balloon is attached to a long piece of clear 16mm film, which runs into a projector at the far end of the room. When the projector is switched on, the balloons are pulled, one by one, toward the machine, where they are released from the film and climb toward the ceiling. As the blank film is played, its clear image projects onto the screen behind the balloons, recasting their forms to create deeply saturated colors that frolic within the warmly textured environment of the 16mm’s projection. The uniquely tactile quality of 16mm film evokes a familiar cultural nostalgia, giving the viewer the sense that she is watching a forgotten image unfold. Yet by exposing the mechanics of the image as we watch it take shape, the work firmly grounds us in the present moment. This experience of viewing process and product simultaneously serves to gently disorient our established notions of how time functions within film’s production, and repositions our conception of the medium as a purely two-dimensional form.

The second performance, Untitled 1, sets up a similarly contained creative system. Here, powered laundry detergent is placed in a cone speaker. When the film projector is operated, the sound of its fan is recorded and looped into the speaker, causing the white powder to jump and dance in time with the audio’s rumblings. The event is recorded with a digital camera at close proximity and projected onto the wall of the space. The patterns and shapes that emerge from the activated powder are at once microcosmic and monumental. We feel as if we are looking at an ambiguous primordial image that could simultaneously represent the Big Bang, volcanic activity, or the frantic choreography of subatomic quarks. By allowing the sound of the projector to initiate, Hart and Drew celebrate the rude mechanics of the film’s instrumentation, and subvert the traditional hierarchy that places image before sound within its presentation.

Emma Hart and Benedict Drew, Untitled Performance, 2009, photo: Marten Elder via Light Industry

The third piece presented, Untitled 2, constructs a scenario in which the physical filmstrip is given further agency. The 16mm strip is run behind the strings of an electric guitar, which Drew holds in front of the projection screen. As the projector is operated, the film strums along the strings of the instrument, creating a low growling noise. Splices along the filmstrip pluck the strings in a rhythmic fashion to punctuate the music at increasingly frequent intervals throughout. The clear 16mm projection is flashed on and off, first erratically, then with greater recurrence as the performance builds to a climax. This unstable movement between light and dark sharply juxtaposes against the stasis of the tableau and creates an atmosphere of suspenseful disorientation.

The ephemeral nature of these performances reverses the traditional understanding of film as a reproducible form. This inversion allows the medium to function fluidly among multiple genres- as sculpture, musical text, and performative agent. By recasting the medium in such a way, Hart and Drew open up film’s potential for further interpretation and offer new ways of seeing. The effect is pleasurably unnerving and, frequently, totally sublime.

Untitled Performances by Emma Hart and Benedict Drew was presented at Light Industry on November 17 in association with Performa.

Lilibeth Cuenca Rasmussen: The Present Doesn't Exist In My Mind and the Future is Already Far Behind, 2009, via Sculpture Center, photo: Photo: Maria Paninguak Kjærulff

Lilibeth Cuenca Rasmussen’s The present doesn’t exist in my mind, and the future is already far behind, presented last Saturday at the University Settlement as part of Performa 09, explores the influences of early Futurist poetry on the artist’s contemporary voice, creating a cross-generational dialogue investigating to what extent today’s feminism can take influence from the Futurists.

The performance consists of Rasmussen’s physical interpretation of seven poems, written by the early modernist poet Mina Loy, and by the artist herself. Loy’s words underscore the work with rich symbolic imagery, while Rasmussen’s sharper tone brightens and provokes. By bringing these distinct voices together in dialogue, Rasmussen celebrates the influence of Futurism on her work while using it as a point of reference to orient herself within the landscape of feminist performance.

The work takes the form of a spoken word jam fest in which the artist’s lyric storytelling guides the audience through a non-narrative journey rife with sensual poetic imagery and feminist self-assertion. Standing alone onstage, Rasmussen explores various embodiments of these poems through vocal and choreographic interpretation. Original music composed by Pete Drungle and Brian Bender, who create eerie dissonance with piano, drums, and guitar, imbues the performance with theatrical effect. The incorporation of video projection, depicting abstract geometrical patterns that meander behind the artist onstage, adds a pleasingly meditative visual element that further frames the work within a Futurist aesthetic.

Throughout the first four poems, Rasmussen inhabits a large white modular costume that bends to create a variety of geometric shapes, alternating exposing and hiding the form of her body according to its mode of employ. During her interpretation of Mina Loy’s She-He-We, a sensual poem exploring points of intersection between masculine and feminine entities, she molds the costume into an egg-like structure that hides her body. For Surfing the Surface, her own poem about the role of self-empowerment within digital culture’s disembodied space, she pushes her body against the fabric of the costume to emphasize its form.

Lilibeth Cuenca Rasmussen: The Present Doesn't Exist In My Mind and the Future is Already Far Behind, 2009, via Sculpture Center, photo: Photo: Maria Paninguak Kjærulff

Later, she completely breaks free of its confines, shedding the costume to reveal a white spandex jumpsuit beneath. She dons a white Afro wig and sunglasses to perform her poem Fuck the F Word. Here, she takes influence from Futurist ideology to reject the use of the term “feminism” and assert the need for a newly imagined identity, proclaiming “Fuck the F, relight the fire/Let the granny feminist retire/Feminism suffers, because of a name/This gotta change, we can attain!” She calls upon women to “Make a promise to never get tame/Be a daredevil and don’t be ashame.”

After speaking a Mina Loy poem that explores the ambivalence of Loy’s feelings about motherhood, Rasmussen ends the performance with her own Artist Song, a poem that renounces the political structure of the contemporary art world. Here, she claims Futurism as an inspiration and rejects the influence of art historical context in an effort to move forward, declaring “Futurism useful for my access/In their spirit, I must detach to progress/Art was never made to last/Cut off nostalgic strings to the past.”

Lilibeth Cuenca Rasmussen: The Present Doesn't Exist In My Mind and the Future is Already Far Behind, 2009, via Sculpture Center, photo: Photo: Maria Paninguak Kjærulff

By investing in a reanimated Futurism, Rasmussen detaches herself from previous aesthetic and cultural influence, and asserts the need for new order. Yet such detachment is more easily asserted than achieved. A scratch along the surface of the work reveals deep feminist influences that run the gamut of the movement. Most notable is her corporeal appropriation of écriture féminine, illustrated in the form of her embodied textual performances. Her direct addresses to women also place her work solidly within the realm of identity-centered politics, with a sprinkling of radical feminist overtones garnishing the text. For all its calls to revolution, her work remains embedded within the very influences she denounces, and could offer more in the way of forward-thinking alternatives.

The piece would perhaps be more effective if both Rasmussen’s text and body were slightly more compelling in performance. The poetry’s adherence to a strict AABB rhyme scheme quickly grows tiresome, confining the language to a set of formal aesthetic regulations that undermine her empowered message. In addition, her delivery of the text is often difficult to understand above the atmospheric music. Furthermore, by confining herself to the center of the stage for the duration of the performance Rasmussen prevents her body from fully expressing her text’s meaning. While the work ultimately offers a playful interpretation of early Futurist poetry, some of Rasmussen’s more radical assertions don’t quite hold up.

Lilibeth Cuenca Rasmussen’s “The present doesn’t exist in my mind, and the future is already far behind”, presented by SculptureCenter and supported by the Danish Arts Council, was performed at University Settlement on November 7 in association with Performa.

Kate Levant splitbroke sheet curve, 2009 Plastics, rubber, fiberglass, broken glass and marker 6 x 52 x 68 inches, via zachfeuer.com

Blood Drive, composed by Kate Levant and presented at the Zach Feuer Gallery, explores the layers of cultural symbolism behind the simple act of giving blood. Effective, if under-realized, the show celebrates the body as a primary active agent in producing useable biological material while gently investigating the limits of socialized connection within an individual-centered culture.

The exhibition is staged in two parts. First, participants engage in the physical act of giving blood through the New York Blood Center, which set up a drive within the gallery space. For us donors, slight physical pain is endured and emotional response evoked as we witness our blood — that encoded material that both defines us as individual and binds us together as a species — flowing out into small plastic bags. Here, the involuntary production of organic matter is consciously introduced as currency into the physical economy of biological exchange , transitioning the role of the body from passive manufacturer to active merchant. By choosing to donate, we perform within the carefully staged medical ritual that facilitates the most direct and democratic contribution an individual can make towards sustaining other human lives. In this intimate physical state, we each become vulnerable and honest.

Kate Levant, highsweep , 2009 Plastics, wood, rubber, fiberglass, broken glass, aluminum and aerosol enamel

The second part of the exhibition is textually based. After donating, participants are given a packet of small booklets to peruse while sipping sugared juice and resting under the vigilant gaze of the medical staff. The booklets are composed of textual material interlaced with graphics by Maude Standish, Kate Levant, Michael E. Smith, and Jacques Vidal, with a photographic essay appendix by Elaine Stocki. An introduction lyrically details the central themes of the work. One leaflet explores the role of the individual in relation to a larger social framework through a narrative account of the role of blood transfusion as ideological vehicle during the formative years of the October revolution. Another focuses on the primary drive of the individual through the connection between the fluidity of performative artistic personality and Freud’s theories of ultimate masochism. A conversation between Jacques Vidal and Noel Anderson reads as a poetic yet focused brainstorm on the appropriation of individual personality within racial identity.

Taken together, these texts read as dramaturgical material that serve to explain and supplement the work from the outside, rather than taking coherent place within the work itself, leaving little room for playful interpretation. A more permeating visual integration of the ideas outlined in these texts would perhaps speak more eloquently to Levant’s message. Why not integrate these richly layered ideas as performance or visual-based interactions instead of including them as a didactic afterthought?

The disjuncture here between these performative and textual elements illustrates a recurrent problem. By compartmentalizing these dual artistic genres, we deny ourselves the opportunity for substantive connection between these forms and ultimately limit both the sensual and the intellectual impact upon the spectator/participant/observer. Kate Levant’s ideas are superb, yet her execution doesn’t quite do justice to their potential.

Blood Drive, comprised by Kate Levant, opened on July 16th and ran through September 4th at the Zach Feuer Gallery.

]]>