installation shot of Harlan’s Cave (2012). courtesy of JTT, New York.

Charles Harlan’s Cave is, according to gallerist Jasmin Tsou, who was quietly painting the walls when I visited the piece, concerned with ‘the progression of certain types of architecture.’ By situating this installation in juxtaposition with an oblique text that describes various civilizations and various archeological artefacts or geographical features — ranging from Puente Viesgo, Spain, in 38,000 b.c., to 1997 A.D. in Smyrna, Georgia — Harlan has done precisely that: his own work concludes the timeline, as the most recent stage within the broad context of ‘caves’ in human history.

If the concept is initially inscrutable in its range, it is simultaneously fairly simple, revealing a deceptively laconic kind of focus and attention to detail that is fascinating and delighting. Ms. Tsou’s matter-of-fact housekeeping speaks to how the installation works: it is just there, transforming the space, as life goes on around it. The specificity of this moment — of taking the idea of the cave and the installation as a point in its overarching chronological progression — is compelling. For me, however, the most interesting and engaging aspect of the installation was its depth and impact as a physical experience. By zooming in on one specific form, with infinite variations, Harlan activates a whole network of experiences and associations, even as the physical experience is unique to being present in this space, at this time.

It’s for this immediacy and focus of physical presence that Harlan’s broad concept — this exploration of the mutation of a geographical features and multiple ideas it elicits — had to take the form of something as direct and grounding as an installation. The experience of the piece is as quietly astonishing as the concept is broad and evocative. How can a large piece of PVD-piping set in unsettling proportions within the small, low-ceilinged confines of a simple gallery, in an unremarkably dirty and clanging street in the Lower East Side, have the same effect, at once shocking and soothing, as the first breath of country air taken when one hasn’t left the city in a few months?

Part of the answer, I suspect, lies in the fact that both experiences are unemphatic but undeniable shifts in perspective. Photographs cannot convey the physical effect of the pipe’s weird proportions, its weight, its unaccented but uncontestable being there. It plays with the senses on every level, simultaneously muffling street noise even as air moving through generates its own barely perceptible hum. This kind of sensory transformation, encountering a moment or object that, quite literally, gives one pause is one of the sadly underrepresented powers of installation.

Harlan’s approach is not particularly concerned with presentational flourishes: another part of the installation, the pickle overflowing its bottle, seeming to strain the glass, is presented with precisely zero drama. This technique is all the more effective for its simultaneous contrast and affinity to the phenomenological effect of the pipe — completely different objects impact the body in echoingly similar ways. I point to the phenomenological aspect of the experience because I think this is precisely where the confident, meticulous thought-work that goes into these objects plays out. In his mid-century classic The Eye and the Mind , Maurice Merleau-Ponty articulates the subtle channels along which this precisely executed work reverberates:

the mystery lies in the fact that my body is at once seeing and visible. He who looks at everything, can also look at himself, and recognize in what he sees the other side of his seeing power. He sees himself seeing, he touches himself touching, he is visible and tangible to himself.

Cave is carefully calibrated to engender precisely this unsettling but deeply present state, and as Merleau-Ponty described, the viewer is both active in it and, crucially observing his or her own participation

From the first moment of seeing Harlan’s Cave through the glass, certainty evaporates. Sightlines are called into question. Can I walk in ? Is this the right entrance ? Do I walk through it, or go around it ? Like that first breath of country air, it transforms its environment through a series of sensorial shifts. It makes its own sound, which changes as you walk through the gallery, from wooshing, to echoing, to the shocking clanking of your own feet. Situated within the tube, you are frozen in time and space even as you continue to move through them. The pipe feels much longer than it is, because the experience of being contained within its full network of sensory impressions — optical illusion, sound transformation, body in space — is so completely transformative, for such a brief amount of time. Looking through the PVD pipe enacts the crucial difference between a door and a portal.

Ultimately, what makes this installation so successful is that it immediately makes you start looking. The viewer is not given the option of remaining passive for even an instant. The Cave’s real success is as a kind of telescoping or magnifying gesture : you will look here now. And what is the « here » in question ? It’s the gallery, it’s the installation, it’s the experience of looking at and being in and with art.

Charles Harlan’s Cave is on view through April 14 at JTT, 170a Suffolk Street, New York NY 10002.

]]>

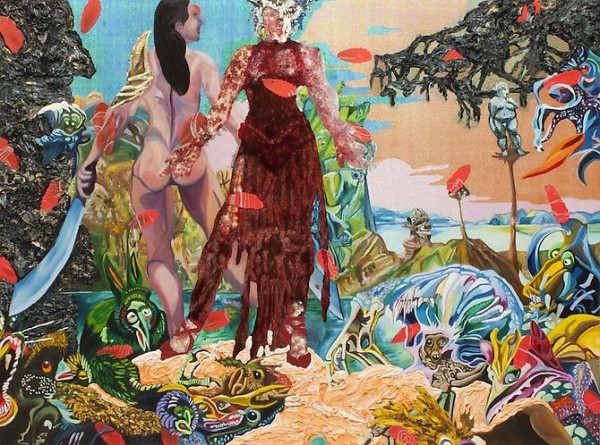

Min Hyung, Dual Side of Female Hero, 2011. Via Freight+Volume

Migration, currently at Freight + Volume, is an intimate show with a broad title. The gallery defines the rapport between four artists as a nomadic quality that brings them to the “support and camaraderie of…large urban areas” like “New York (or London or Berlin).” And if this feels a bit too vague and general, the exhibition is minutely scaled and benefits from the attendant specificity; it doesn’t miss the mark, but it could go further.

The work is interesting less for its nomadic creators or themes – whose divergences often make cohesion difficult – than for its focus on the perceptual refractions of the physical, often-feminine and unstable body. This is especially true for the most compelling pieces on display, by Min Hyung and Eunah Kim.

Eunah Kim, Lucy's Pelvic Bone, 2009. Via Freight+Volume

Min Hyung’s big canvases feature an exhilarating diversity of texture and depth, so thick and swirly that they sometimes look edible, like saltwater taffy. Working in a mode we might call ‘epic whimsy’ she flings, swirls, dots, daubs and carefully etches varieties of paint ranging from sheer, gold-flecked Mattel pinks to dense, fat edges whose viscous darkness sucks light from the central figures. These, nevertheless, remain central. Ms. Hyung says she is inspired by Savage Beauty, the McQueen show currently drawing crowds at the Met, and in particular by McQueen’s assertion that “I want to empower women. I want people to be afraid of the women I dress.” Even if this idea of empowering “women” doesn’t quite scan – either in Hyung’s paintings or McQueen’s creations – a kind of archetypal warrior woman is certainly in evidence. A blue-white feminine figure, her back turned to the viewer and holding a sword aloft is a recurring motif in two of the three paintings, in the third she holds a vaguely umbilical thread or rope reminiscent of Frida Kahlo. The influence of fashion, in particular of preparatory sketches for couture collections, is clear in the leggy, statuesque figures, scaled for spectacle, that double down on the McQueen-ish themes of facing/displacing, masking/revealing and directional dislocation. Discerning the fronts and backs of the bodies, despite their flat, declarative lines, is a challenge. The heraldic quality and mutable nature of these bodies adds medieval iconographies to an epic list of references that includes Bosch, Botticelli, Max Ernst, and Delacroix. Each of these operates on and around the body “real” and the body represented. Theorist Jeffrey Jerome Cohen:

Medieval bodies were caught between gravitational forces that pulled them at once toward a fantasy of impossible completeness….and at the same time confronted them with a daily spectacle of of the flesh dissolving into pieces, of bodies composed of metamorphic humoral fluids, of the corporeal as the scene for the staging of magic, holiness, perversity, wonder. Bodies were, quite simply, caught in a process of erupitve becoming.

Hyung’s work shares with medieval bestiaries this fantasy of impossible completeness, of the volcanically transformative potential of the body, even as the contemporary moment injects a mechanical, quasi-bionic quality. The flat figures at center, gilded and half-armored, work as a visual springboard for an entirely other network of bodies; each style relying on another to highlight its specific impact. At the bases of the canvases the eye endlessly recombines a careful mess of totemic, fragmented people and animals, reminiscent of illustration, to produce a menagerie of fantastic beings.

Eunah Kim, Happy Lung Flags, 2009. Via Freight + Volume

If Huyng is playing with skin, with the multiple registers in which the body’s outside is perceived, Eunah Kim was obsessed with its interior. Kim, who passed away from lung cancer last year, re-worked the intimate, crushing experience of her own insides. Her Happy Lung Flags are exactly that: a series of three flags “made…as a tribute to her besieged lungs and represent the artist’s aspirations for health and happiness.” ‘Aspiration’ is an excellent word here, because Kim’s work is wonderfully devoid of any overt sentimentality; like aspiration, it is direct, action-driven and self-reliant. Rather than impeding emotion, this spareness sharpens it. Hence, Lucy’s Pelvic Bone, a simple and affecting bronze cast of said bone, mounted at a tiny woman’s eye level and without further adornment on the blank expanse of wall. The pelvis is a touching choice, particularly for its sensual, generative functions, which Kim froze in time even as it is rushed from her. It is extraordinary how directly and delicately Kim’s work captures an unimaginable situation even as it refuses maudlin declaration. As the natural lines of bone softly carve the space, making it resonate with their symmetry, the shine of the bronze calls attention to this same effect and codes it with a one-note mark of value. ‘This shines,’ the glint suggests, ‘it is worth something.’

Meridith Pingree, Magic Curtain, 2011. Via Freight + Volume

Presented in a small room towards the back of the gallery, Kim’s work is deprived of some of the frame of scale it deserves. This may be because Meredith Pingree’s “kinetic sculptures” and Genevieve White’s installations require more specific kinds of spaces. Pingree’s Magic Curtain looks, at first, like nothing so much as a room-divider in a 1970’s beach house. Sit with it a moment, though, and it reveals its delicate mechanisms, its sinuous, amphibian movement, as it quietly settles you in time and space. It is an unobtrusive presence, one that provides a lovely corporeal context for Migration’s carnal wanderings.

]]>

Tiny Creatures at Closing Creatures, via their Facebook page

Chris Kraus is a nearly prolific writer who keeps fashionable intellectual company. She’s on the faculty of the European Graduate School with Slavoj Zizek and Manuel DeLanda; she has won numerous prestigious awards and founded a division of the semiotext(e) series dedicated primarily to women’s voices in fiction. Her books of fiction and criticism, with glib, wry, attention-grabbing titles like Aliens and Anorexia and I Love Dick, have garnered praise. Her latest, a slim volume in the semiotext(e) intervention series called Where Art Belongs, is described as follows: “Chronicling the sometimes doomed but persistently heroic efforts of small groups of artists to reclaim public space and time, Where Art Belongs describes the trend towards collectivity manifested in the visual art world during the past decade, and the small forms of resistance to digital disembodiment and the hegemony of the entertainment/media/culture industry.” For all its faults, Kraus argues, the “art world remains the last frontier for the desire to live differently.” The claim is ambitious, but it also begs the question of what, exactly, is being resisted, and whose desire is being reflected. Where Art Belongs is an interesting, but ultimately uneven, effort at answering its own title question.

Kraus takes a critical approach that strives to be radically democratic, suggesting decades of interest in participatory and the influence of the DIY nineties. There’s a delightful arbitrariness to the works she chooses, which seem as much informed by personal experience as by overarching philosophical, ethical and narrative concerns. The first essay, for instance, on the art collective Tiny Creatures, gives credit to a series of haphazard and often juvenile happenings of dubious impact, both inside and out of the art world. This goes back to the difficulty of measuring, for example, how LA Chinatown’s art scene in the early 2000’s changed our relationship to art or life. Without a focused metric of measurement, the central question becomes not only impossible to answer, but the answers make the question itself look a bit silly.

Kraus correctly realizes that the only way to engage with something so broad is through targeted analyses. Consequently, the book is organized into four sections with specific, pithily oblique titles, like “Body not Apart” and “Drift”. Though its structure is ambitious, the writing of Where Art Belongs doesn’t hold it up as well as one would like. Its lack of tonal consistency is more confusing, even jarring, than charming or productively destabilizing.

Take, for instance, Kraus’s dealing with Janet Kim’s Tiny Creatures, a loose and deliberately (even stubbornly) unstructured series of Los Angeles-based events and network of artists united by Kim’s “Tiny Creatures Manifesto.” “In the winter or spring or maybe the summer– depending on who and when you ask– of 2006, Janet Kim moved into the storefront at 628 North Alvarado that would become Tiny Creatures.” Kraus affects this tone – which I suspect is a strongly love-it-or-hate-it affair – on and off throughout the book, a kind of wasn’t-it-cool deadpan casual that reads a bit like a Rolling Stone article about the early days of Nirvana. Here’s a description of Kim during one of their conversations: “She pauses and puffs on a $1.50 cheroot […] Teaching piano and working part-time as a coffee-shop waitress in Montebello, she felt completely alone.” Kraus is eager to glamorize the starving artist working a dead-end-job and feeling alienated. She does it a lot, and her focus on veneer is often distracting, preventing the reader from getting a sense of the art. There are many moments when Kraus does let the work shine through, and those are exciting and engaging, but they are too often interrupted by the writer’s riot grrl routine.

Kraus’s work spans several genres, and the strength of each section is determined not only by which genre takes precedence, but also genre’s relationship to the work itself. The Tiny Creatures section, for instance, better succeeds as a microcosmic cultural history than as a work of art-philosophy or criticism. This may be because the works in question are not that interesting, or because the writing about the works is unsuccessful in piquing our interest, or, finally, because what is interesting is not the work but what happens around it. “Pioneered by MFA graduates, [In 2006] Chinatown was still the epicenter of Los Angeles art,” Kraus writes, raising charged issues of class and praxis with just three little letters. In referencing this “scene” in this way, Kraus creates (or at least, doesn’t resist) the division between those who “get it” and those who don’t, letting us know, as she does, that that scene is over, that Chinatown is no longer the epicenter of LA art.

Insider-ness is a problem in other places; too, like in Kraus’s description of a community art space in the border town of Mexicali Rose: “Edgar Moreno, a pizza delivery boy, strapped a video camera onto his bike to create a poetic montage of city lights that struck me as more accomplished than most MFA-program neo-structuralist films.” That’s intended as a compliment, but the implied surprise and accompanying condescension at the fact that a pizza delivery boy could create something “accomplished” (whatever that means) is intense in its class implications, and more than a little off-putting. You Are Invited to Be the Last Tiny Creature is the essay that raises the question most sharply: is Kraus matching her cadences to the aesthetics of the scene? Or is she allowing them to intervene where they don’t contribute much? I suspect it’s the latter. Happily, later essays deal with work that’s more interesting, giving Kraus space to step back and let us see them through a less stylized intermediary.

Bernadette Corporation, The Complete Poem installation view, via artnet

While not immune to the flaws of the subject in question, Kraus’s study of the Bernadette Corporation is the most satisfying engagement with the questions the book sets out to answer. Engaging with the Corporation’s production of an epic poem displayed as art in a commercial gallery, Kraus finds the perfect dynamic subject for her inquiry, and this allows her to do some really fine critical work. “For dozens of pages, the poem turns on the formal conceit of “branding” the text by including words beginning with the letters B and C in each skinny line.” In addressing the materiality of the text and the physical shape of the letters, Kraus details how the conceit — “branding” — is successfully carried out at the level of form.. We see how the Corporation brands itself (as an artistic presence, art-world commodity, participant in and perpetuator of gallery economies) through the piece’s construction. Kraus’s dexterity in mapping the internal consistency of a “successful” piece reflects a sensitive and incisive critical approach that the book could stand more of. These focused and intriguing observations are much more powerful than sweeping generalizations about “the raw material of poetry.” Her articulations of place are also illuminating, as when she writes, “By sheer proximity… the poem, though written in turns by individuals, assumes a single collective voice.” Kraus, though, has an advantage here. Through the Corporation’s focus on genre, space and place — and their strongly articulated sense of purpose — Kraus can ask, where does art belong contextually, historically, geographically, philosophically, spatially? The philosophical consistency of their work gives Kraus (and the reader) a solid springboard for consideration, and her essay succeeds in raising huge questions in minimal space.

The various artistic practices examined here are relatively successful at demonstrating how it is possible to embody the kind of “living differently” Kraus claims. In some ways, it’s hard to see what artists are living differently from — after all, art-school grads working in each other’s ad-hoc spaces hardly represent a new phenomenon. These unanswered issues make it difficult to say with certainty whether Kraus has made her point. When she goes on to write that “Art direction succeeds to the extent that it locks down our fleeting perceptions of an ambient present into coherent images. There’s an amazing potential contained in that freeze”, she gives hints at what she’s getting at, and begins to justify her approach. If we accept that artists are searching for a new kind of living, documenting their approaches and placing them in relation to each other gives us a context in which to understand their particular relationship to the art-world, and their larger relationships to structures outside it. Consciously or not, Kraus is also offering an excellent criticism of her own work. The works she chooses to freeze — and the alternatives they represent — are exposed to our inquisitive gaze, but they also suffer some in this particular becoming coherent of their otherwise fleeting image.

]]>

Filip Noterdaeme, HOMU Booth, 2010. Photo by Daniel Isengart

I like the art world and the art world likes me—at the EFA Project Space through 5 March suffers from a slight identity crisis. By turns engaging and muddled, the questions it raises, not all of them rewarding, are more about the show as a whole rather than individual pieces. What, for instance, is a “ ‘bootleg’ artist” (as organizer Eric Doeringer has styled himself)? Can’t everything be “read as either sincere or sarcastic” (as the press release instructs us to read the title)? Perhaps most pressing is the first question the title suggests—which art world? We’re meant, of course, to immediately understand the “New York art-world-as-hegemon” construction, though its solidity is anything but universally established. The conception and tenor of the show are shifty. In true children-of-the-nineties style it refuses to be really serious, while being really serious, preemptively shielding itself from attack by calling your attention to its inevitable shortcomings, and to its own painful awareness of those shortcomings. Suffice to say it was the first time in years I had thought of A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius.

The wide range of depth and quality is interesting for the prevalence of two kinds of fin-de-siècle themes: one, an obsessive kind of cataloging reminiscent of the 19th century Decadents (cf. Huysmans’ exhaustive descriptions of Des Esseintes’ home décor, library and art collection in À rebours, or Zola’s minute recreations of laundries, bars and apartment buildings in the Rougon-Macquart); the other a knowing, overly personal, faux-folksy, quasi-naïf intimacy that recalls the end of the more recent century.

Jennifer Dalton’s Every Descriptive Word used to Describe Artists and their Work in Artforum’s ‘Best of 2007’ displays some of the former’s palpable monomania. It’s exactly what the title promises—a long white sheet of paper, thousands of words written in a minute, careful hand coursing down the page, which extends beyond the vertical wall space and continues across the floor. Copying them, in pencil, feels like an appropriation: an artist’s ephemeral, physically personal re-interpreting of the self-ascribed permanence of the printed page. It’s a simple, strong idea executed successfully and with intelligence. Dalton chooses to divide the modifiers into two columns, one for men and one for women.“Modest” stands out in the latter.

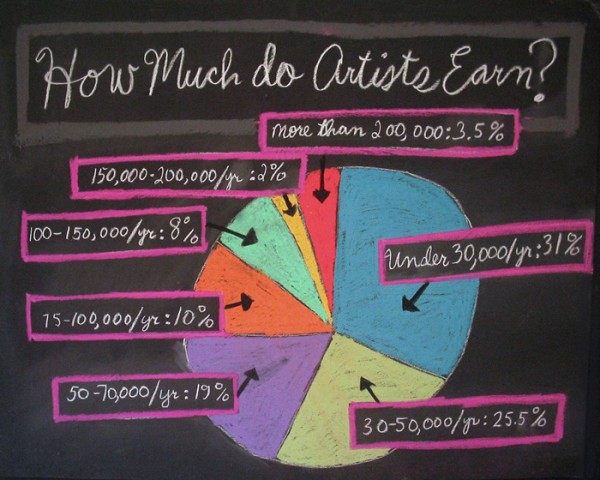

Jennifer Dalton, How Do Artists Live? (slide from a 35mm slide show), 2006. Via EFA

Artforum makes other appearances in the show—perhaps it’s assumed to be synonymous with the art world of the title. Conrad Bakker’s Untitled Project: SUBSCRIPTION [ArtForum International September 1969-June 1970] (Artist’s Proof Edition) are carved and painted covers of the magazine that, like Dalton’s re-framing of the words, re-appropriate the perceived visage of power. They demonstrate, again, the preoccupation with cataloging, reproducing and collecting objects deemed aesthetically important—and, in this case, commercially powerful. Pieces like Bakker’s and Dalton’s are the strengths of the show: direct, coherent and effective engagements with each artist’s specific interpretation of what “the art world” means. Through words and representation, Bakker and Dalton engage with a significant textual arbiter of the image.

The overly familiar register of the most recent fin-de-siècle, its Brooklyn-cutesy trend towards an earnest voice that somehow manages to never sound sincere, is exemplified elsewhere by a series of letters by Filip Noterdaeme, founder of the Homeless Museum of Art. Addressees such as “Dear Stranger,” “Dear Art Museum,” “Dear Artist,” the Director of the New Museum, Jesus and so forth receive messages imploring them to “Please stop going to art museums”, or “Please stop attracting the masses”. The missives then go on to inform the recipients of their particular shortcomings, of the evils they are supporting (“rehashing the same ideas forever, etc.”) and of the threats they pose to “the passionate and carefree world of the amateur.” The letter-as-medium is not an uninteresting concept, the problem is in the homogeneous, self-conscious precocity of the writing. The “Dear…” salutation, the casually friendly, pseudo-arch tone, the surfeit of exclamation points all characterize an overwhelmingly twee aesthetic that belies the “Sincerely” with which each letter concludes. The letters might be read as a kind of fragmented manifesto, but it’s a manifesto that tries to be too many things without fully grasping any of them. In spite of themselves, they come across as museum pieces, the archives of a particular aesthetic.

”Conrad

Doeringer didn’t set himself an easy task, nor an uncontroversial one. I like the art world… engages with a series of massive questions and tries to define several sprawling concepts. It will inevitably elicit criticism and court conflict. Its ambition is admirable even when some of the individual works fall short. Even these, though, when taken as part of the whole, reveal tendencies and preferences in contemporary art — whatever world that may be.

]]>

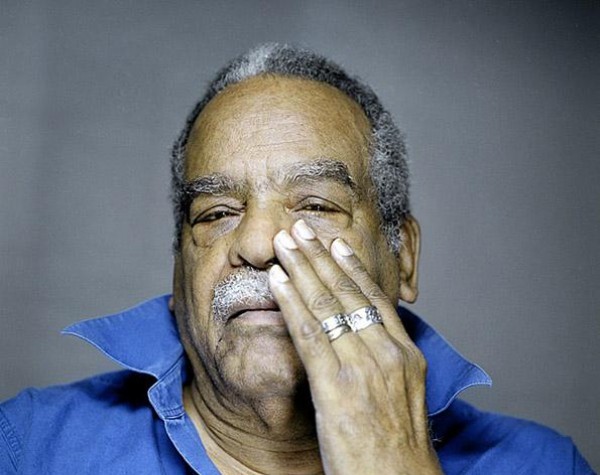

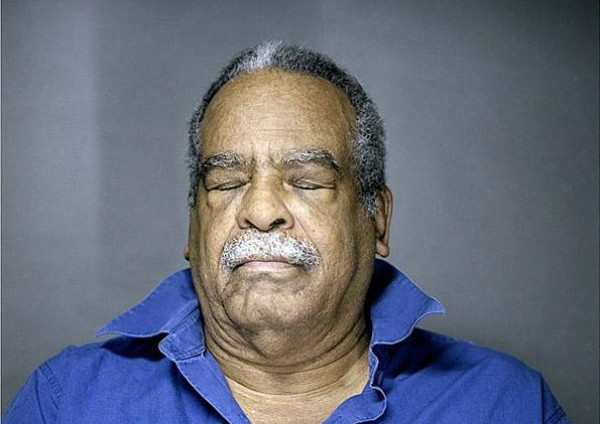

Edouard Glissant. Via Olivier Roller

Ce sage marin, mesuré diseur…Il vient, enfant, dans le premier matin. Il voit l’écume originelle, la première suée de sel. L’Histoire qui attend.

(This wise man of the sea, measured teller of tales. He comes, a child on the first morning. He sees the primeval foam, the first sweat of salt. History, waiting).

– Édouard Glissant, Le Sel noir.

Of which Glissant do we speak? He was irreducible in person—a force of nature who spoke barely above a whisper. In death, —“scattered among a hundred cities”— how do we write about him? How do we write about the extreme, pitiless generosity of his vision, which respected the world too much to condescend to it? Glissant knew he was a genius as surely as we knew him to be. This is no paean to the simple man behind the novelist of La Lézarde, the playwright of Monsieur Toussaint and Le Monde Incrée, the world-expanding theorist of Poétique de la relation. There was nothing simple about him.

Should I write, then, about our own experience of the poet, intimate and local? About the Monsieur Glissant who every Friday received a group of students in his living room, listened to our poetry (his attention had a bright, hyper-focused quality: never frenetic it was rather piercing and enervating and unmatched), talked to us—incredibly!– like poets? The man who, in his old age, with his carefully-measured glass of red wine (never anything so pretentious or precious as the fashionable biologique) in one big hand, the other resting, more often than not, on his cane as he teased the promising syllables from our efforts? These we had brought, quaking with elation and laughing, sometimes, at the serendipity of this surreal dialogue with someone who might so easily seem beyond our reach. The one who saw through us, eyes half-closed, and offered no indulgence for our self-deprecation, no quarter for our dissimulation, only infinite patience. Ought I to write about the moments when, in gleeful anticipation of a coming trip, he would sing to us, “Martinique, c’est très chic.”? Or about the afternoon when we were joined by the young, brilliant Haitian poets he welcomed after the earthquake, who read to us poems written on airplanes rising above the ruins of Port au Prince? Or perhaps I can write about the phrases that could only come from him, illuminating a work in one sentence: C’est une poésie de la fulguration. More simply, I can say: we became poets because he believed us to be. To receive his attention was daunting, a profound challenge; the Martiniquan writer Raphaël Confiant wrote, for years, almost in spite of Glissant:

j’avais avoué avoir lu, à l’âge de 18 ans, trois pages de son fameux roman «La Lézarde» … et avoir refermé immédiatement l’ouvrage pour ne le rouvrir qu’à l’âge de trente ans. Pourquoi? Parce que j’y avais découverte une écriture si puissante que je m’étais dis que si jamais je m’y enfonçais, si je continuais à lire l’ouvrage, jamais je ne pourrais devenir écrivain à mon tour.

(I told him I had read three pages of his famous novel La Lézarde at the age of 18…and closed the book immediately, not to open it again until I was thirty. Why? Because I had discovered in it writing so powerful that I told myself if I ever sank into it, if I continued to read the work, I would never be able to become a writer in my own right)

It’s been hardly forty-eight hours since Édouard Glissant died. His death was not unexpected, but it was uncharacteristic. On the Internet, a torrent of homage whose eloquence and polish bespeak his long illness as much as the caliber of writers he influenced (Bernabé, Chamoiseau, Confiant and on and on); a generation now facing the tremendous, electrically charged responsibility of carrying on his work. It was not unexpected. Writing, we prepared for what we knew was not possible.

We must not protect his legacy—protection is not something he would abide. We do not honor him by enshrining his work in rigid interpretations, but by throwing it open, wide to the world. We honor Glissant by reading his work and by sharing it.

Any number of platitudes—which, one imagines, he would have swiftly dismissed with a « Ne dites pas de bêtises.» —seem inevitably to follow a death of such significance. « He changed everything in my life, forever », we, his students, have said to each other, with no twinge of hyperbole. « I feel like my heart is gone ». A former student: “A library has burned down.” To look beyond platitude is to look for the intimacy in the universals he interpreted, the most intimate made the most universal. One woman, his student and friend, will dig out a fire pit and burn a dead tree in her frozen back yard on Staten Island, and in the scent of pine needles, in the showering sparks, read his words to the frigid winds. I, trying to read Auden’s elegy for Yeats at the suggestion of an understanding friend, am myself frozen by the words “He became his admirers.” My late uncle, a playwright, refused to leave his native Havana, even in appalling economic circumstances—the most intimately local, he insisted, was the only setting for human work. The only work, in other words, worth doing.

To root him (with no disregard of his preference for the rhizome) in his hyper-local universality, we would think of the young man, the son of a plantation laborer born in 1928 in Martinique, formed in the lycée system. The world of the Antilles– their history, yes, but also their sights and smells and sounds, permeate his writing, his thinking. The words he would later write about Saint-John Perse (Saint-John Perse et les Antillais) are as readily applicable to himself:

L’Ilet-les-Feuilles. Mer et forêt. Cette nature qui enjendre et régente le style…Voies toujours ventées: l’en aller, le maigre, le fluide, la Mer. En même temps, une démesure architecturée, des pourrissements végétaux, des lumières de sel accrochées aux racines violettes…La nature parle d’abord en nous.

(L’Ilet-les-Feuilles. Sea and forest. That nature, which gives birth to style and rules it. Always-windy paths: the departing, the meager, the fluid, the Sea. At the same time, a crafted excess, vegetal putrefactions, salt lights hanging from violet roots. Nature speaks first within us.)

Nature– the violently fecund nature of the Caribbean, alternately crashing and delicate — always spoke in his poetry, in his plays and in his theoretical writings. And it was this ineluctable attention to the crucible of the new world, his certainty in the value of that unique and multiple experience, that gave so many literary voices– from Guadeloupe and Martinique and Haiti, but also from every corner of the globe– the conviction to assert their own subjectivity, the courage to take their place in the tout-monde he envisioned, and the implements to enter, as they were already entered, into relation with the wide world.

Via Olivier Roller

He arrived at the Sorbonne in 1946 (itself no small feat), plunging into philosophy and ethnology and the myriad circles and colloques devoted to discussing poetry and culture and writing — all set against the increasing urgency of securing independence for the colonies. He was the friend of painters and writers and politicians, the interlocutor—and frequent, eloquent critic—of Césaire and Fanon. (At our first meeting, on learning I was Cuban, he informed me, with a sly gleam in his eye, that he had had many conversations with Fidel Castro. Later he would tell me about his friendships with Wifredo Lam and Nancy Morejón). He worked ceaselessly in those years (as he would until it was no longer physically possible), agitating for the right of the colonies to self determination, and writing, always writing.

In some of his earlier poetry we see the architecture of a life’s work. In Le sel noir, we find an odyssey of wandering unfettered by natural or temporal limits– salt and foam, Carthage and African storytellers, metered by the mutable, inexorable sea. Les Indes (The Indies), whose poetic density surpasses the lyrical, is an epic of 1492, its eloquent genesis. Its six cantos, L’Appel, Le Voyage, La Conquête, La Traite, Les heros, Relation, (The Call, The Voyage, The Conquest, The Trade, The Hero, Relation) shaping the Antilles even as they trace their history in verse. In the holds of the slave ships, in the bodies scattered across the bottom of the ocean from Africa to Europe to the Americas, in the eyes of the conquerors, in the harrowing poetics of encounter, Glissant shows us the new world. Les Indes is Glissant’s entry into the pantheon of epic poetry, but it is also in a very direct, very specific dialogue with another poem of genesis, this one Guadeloupean — Perse’s Vents (Winds) from 1946 about whom Glissant wrote voluminously. Writing which bespeaks his generosity, his admiration for admiration. Perse, the Berber novelist and playwright and independence hero Kateb Yacine: in these Glissant heard the murmurings of the chaos-monde. His was a lifelong battle against the homogenous, against globalization-as-standardization. He taught us not to read things (cultures, people, poems) in such a way as to translate them, violently, into our own image, but instead to honor their incomprehensibility and mystery. He was opacity’s great defender, the staunch opponent of imposed explanation and weaponized transparency.

Only the biggest questions of poetry– the movements of humanity across oceans and time—are constant of Glissant’s work. Yet it was his novel La Lézarde (The Ripening) that won him the Prix Renaudot in 1958. Because of his organizing on behalf of colonized peoples, and particularly his vocal sympathies with the Algerian independence movement, de Gaulle forbade Glissant from leaving France for six years. In 1965 he returned to Martinique, using the funds from his Renaudot to establish l’Institut martiniquais d’études and the journal Acoma. Acoma is a tree that grows in Martinique, notable for the fact that a new tree will grow from its bisected trunk (this summer, after his heart attack, we leaned on this image).

He would live over the years in Paris, Baton Rouge and New York, always engaged, always seeming somehow more alive than the rest of us. In his theoretical writings (L’intention poétique, Poétique de la relation, Discours antillais, Introduction à une poétique du divers and on) he parsed poetry, never explaining, always deepening. Poetry was revelatory when Glissant read it. He revealed networks of encounter, a tout-monde (an all-world) of constant openings, what he called a pensée archipélique— a philosophy inflected by the multiplicity of the archipelago rather than by the totalizing continent.

The obituaries, one feels, are all wrong. As though the death notice of one so avidly alive could be anything but. “Caribbean militant”, “Martiniquan writer.” I suppose he is those things, journalistic shorthand for a man who explained to us, its makers, just what the world could be. Here is Professor Glissant, in Louisiana, finding again his plantation cosmologies, putting America in context for us, writing Faulkner, Mississippi. In 2007, the seminal manifesto Pour une littérature monde, of which he was a signatory with other luminaries like Tahar Ben Jalloun, An anda Devi, Maryse Condé. Later, a Distinguished Professor of French at the CUNY Graduate Center, writing with Patrick Chamoiseau L’intraitable beauté du monde, (The Intractable Beauty of the World) his address to Barack Obama, the first métis President, reminding us of his election’s significance. He knew the necessity of his voice.

To the students and poets and thinkers and writers he touched now falls the responsibility of carrying on his work, of living in the world he opened to us. In the coming days, francophone radio and press will dedicate programs to him, to discussing the poet, the playwright, the novelist, the political thinker, the literary philosopher. Those of us who had the astonishingly rare privilege of knowing him, who, by luck or chance or obsession were brought into his orbit, will find comfort in remembering him as Confiant does:

]]>Chaque soir, ce dispendieux, cet homme au grand cœur, tenait table ouverte, dans sa maison située au bord d’un lac et nous, les participants au colloque, l’entourions comme s’il avait parole d’oracle.

(Every evening, this expansive, this great-hearted man, would welcome us to his table, in his house at a lake’s edge, and we, participants in the symposium, would surround him as though he spoke the words of the oracle.”)

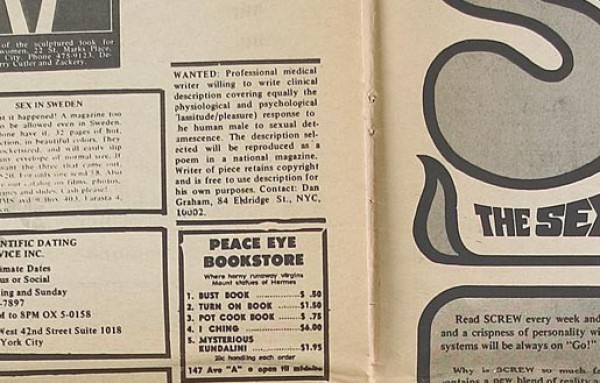

Dan Graham, Detumescence, 1969. Via ZieherSmith

This past December, T.J. Clark, writing about a major Cézanne exhibition at the Courtauld Gallery for the London Review of Books, started out with a rather sensational claim: “Cézanne, whose work was the touchstone for critical thinking and writing on art for more than a century, cannot be written about any more.” The qualities we recognize and respond to in Cézanne are, he writes, “remote from the temper of our times.” Despite the bombastic beginning, Mr. Clark is certainly too wily to devote an entire piece on Cézanne to not writing about Cézanne, and in fact goes on to praise him to the skies, even as he maintains that such praise is anachronistic.

I was reminded of the possible impossibility of re-reading/writing the giants of the twentieth century by the ZieherSmith gallery’s exhibition Sculpture in So Many Words: Text Pieces 1960-75. The exhibition, as we are proudly informed, is “curated by Dakin Hart.” Leaving aside any issues raised by the current popularity of “curated”as a verb (not to mention “curated by”, which passive-voices the work into a bizarre state of submission), its intention is quite interesting. The press release uses a lot of words to inform us that, essentially, the ephemera around sculpture, what usually operates in the wings of the public’s interaction with the work, such as artist’s announcements for performances, newspaper ads and the like, are being shifted to center stage. There is a certain wariness accompanying the archived marginalia of the conceptual. How many times can we keep shifting the frame before the exercise becomes institutionalized in precisely what it seeks to transcend? In many ways (and this is hardly original) the vanguard impulse stops “working” the minute it’s put into a museum, re-interpreted, or in any other way situated.

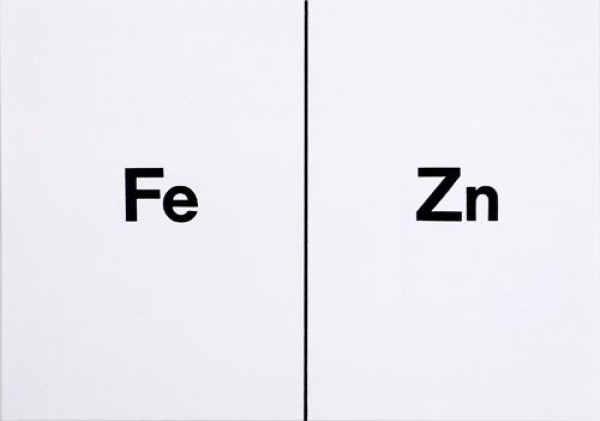

Carl Andre, Fe Zn, 1975. Via ZieherSmith

The particular issue of situating this work– of fixing it in time and space– is a defining problem of Sculpture in So Many Words. Hart, in fact, locates it very precisely (or not at all, depending on your perspective) as tracing “one important, largely unrecognized route by which Duchampian conceptualism and Cageian time-based process theory coalesced into the practices that constitute much of contemporary art.” It locates contemporary notions of sculpture– and of what sculpture can be– at this particular point of contact (affinity? affiliation?), which, really, is the only way the exhibition can make sense. But is it necessary as an art show, rather than as part of a museum collection? I remain unconvinced. So Many Words exists in an uneasy twilight between the curatorial and creative that seems to create as many problems as it opens possibilities. Hart’s exhibition reflects the give-and-take, on-the-one-hand-but-then-again spirit of Dadaism reworked in ’60’s and ’70’s conceptual sculpture, but does so in a way that highlights its characteristic evasion of meaning in a negative sense. We are left with confusion rather than with the visceral impact that made these works speak (or that made the words work) despite, and because of, the extremity of their abstraction, their rejection of genre. This is the show’s chief source of frustration and interest.

John Lennon and Yoko Ono, War Is Over! If You Want It, 1970. Via ZieherSmith

The exhibition succeeds on many levels, though too often it’s maddeningly difficult to decipher how many of these successes are intentional, despite Hart’s wordy description. It’s beautifully arranged, with a consistent logic that prizes thoughtful details and careful spatial pacing. Hart is canny enough, for instance, to have our first encounter be Allen Ruppersberg’s “thank you, mr. duchamp. would you close the door please? thank you.” affixed to the wall in such a way that you do, in fact, have to open it. It’s the kind of hands-on, witty engagement with the audience that made this period of sculpture so engaging. What’s more, having Duchamp explicitly acknowledged from the outset, verbally and through physical experience, though an obvious choice, is still a necessary and intelligent one, showing a self-awareness that warms us to the rest of the show. Fred Sandback’s Conceptual Constructions, simple lines on white paper with declarations like “There exists a sculpture consisting of all patterns of light on retinal surfaces occasioned by the existence of this statement, and of nothing else” are great fun, in the best spirit of cerebral, syntactic games of text and medium. Yoko Ono is well represented by her iconic War is Over if You Want It Christmas card as well as by less ubiquitous, equally engaging works like Light Piece from Grapefruit. The satisfaction, derives from seeing important work and its accompanying ephemera, more than from any essential or edifying re-framing accomplished by presenting these as text sculptures. The centrality of that potentially rich tension is never really clear beyond the Ruppersberg.

Gilbert & George, Any Port in a Storm, 1973. Via ZieherSmith

Hart’s successes, then, are as much art-historical ones as they are any groundbreaking re-working of curatorial practice. An interest in sculpture, particularly “conceptual sculpture”, often connotes a certain fetish for the object. It becomes, at bottom, about things filling space with an interesting, moving, or otherwise engaging presence. In that sense, intentionally or not, the exhibition succeeds (and how sad, though of course understandable, that we can’t touch these objects of desire), since we have the satisfaction of engaging with everything that surrounds some very important work. For those with a fondness for the neo-avant-garde scene of the ’60’s and 70’s, the show is not to be missed, simply because it offers such an intimate and unpolished experience of that moment. As a collection of fascinating objects, Sculpture in So Many Words is beyond reproach; its challenge is in convincing us that all these text pieces actually work, independently, as text pieces or that, deprived of their referents, they do in fact represent Mr. Hart’s “language lab” of contemporary sculptural practice.

]]>

Johann Arens, untitled (Re-understandings), 2008. Via Scaramouche

I confess that the press release for the Scaramouche gallery’s current exhibition, Of many one, which announces its purpose of ‘bringing together a group of eight young London-based artists,’ made visions of taxidermy-d sharks and unmade beds dance in my head. Roughly 20 years after the height of the Saatchi/YBA phenomenon (‘Sensation’? spectacle?), to code oneself a “Young British Artist” still carries some heavy baggage, and tellingly, they are not all British, these Londoners—this is one of many small details that make Of many one so very much of the here-and-now, with the attendant problems and possibilities.

If Saatchi’s promotion of the YBAs, with their extravagant materials, elaborate installations, prankish bad behavior and (more-than a) whiff of entitlement exemplified the driving, booming, globalizing nineties, Of many one might offer a counterpoint tinged by a Glissantian mondialisation, an artistic praxis that celebrates the local, diverse rapports of difference on an intimate scale.

Chas Higginbottom, Spanish Woman With a Rose, 2010. Via Scaramouche

You have the option, when seeing the exhibit, of reading it as the press release wants you to, as a somewhat convoluted play on Italo Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler, the sort of Borgesian-choose-your-own-adventure-absurdist-chess-game of a book that performs all the hallmarks of a postmodernist literature: self-referentiality, unstable narrative structure, recursive chronology, blurred boundaries between interior and exterior and so forth. It’s a lovely novel and an apt suggestion, but not a necessary one: the conversations between the works speak for themselves, in multiple ways, and it seems best to be wary of such a specific reading anyway.

So, we can push the esteemed Mr. Calvino aside for the moment (or not) and see the works themselves. The first piece in the gallery (and by this I mean the one closest to the front door; one of the strengths of this exhibition is that the pieces are placed in such a way as to make any number of itineraries possible) is Chas Higginbottom’s contemporary “riff” (his word—or the gallery’s) on the idea of the readymade. Comprising elements of the erotic, the confectionary and the mechanical, toying with scale and angle and the gaze, the sculpture/installation displays a kind of witty Almodovar-tinged excess of sex, pathos and consumption. Delightfully tacky neoclassical podiums displaying women’s lingerie balance on what look to be cake-shaped hatboxes; a pair of wheels cowers under a sort of tripod whose topper might have belonged to the Mad Hatter. The almost-tripod suggests an almost-capture of the scene, but it is left unresolved; its comic, sweetly mocking, yet nuanced completion lie in this irresolution. The Mad Hatter visual is a good one, for in many ways this is a sort of polylingual visual and aural (mad) tea party. This confusion of subjects and frames, of the limits of the entity or event, is the common note in these disparate works. In Hans Diernberger’s Kampfbereit, a series of photos of battleships lose their edges, their horizons lose their placement, everything is waiting in an uncertain space, and because it is waiting, it’s in liminal time. Destabilizing the horizon questions not only the divisions of the horizontal/vertical space, but the depth of the image. Likewise, the metaphoric horizons – the limits of vision – are no longer solid.

Hans Diernberger, Kampfbereit I, 2008. Via Scaramouche

If space and depth are displaced (or misplaced) in Diernberger’s work, in Rehana Zaman’s Diagram of an Event, the time, as Hamlet said and Deleuze echoed, is out of joint. A diagram of time, reducing four dimensions to the representational two, destabilizes itself, undoing its own order and rationality even as its mode of communication is implicitly described as an attempt to impose order and rationality. It’s an impossible diagram of the intangible.

Laura Morrison, Mens Extra Good, 2010. Via Scaramouche

Laura Morrison’s wet clay sculptures play with limits as well, but her central metaphor is the body rather than the natural world (precisely, the seascape) of Diernberger’s series. A torso emerges from the floor: twisted, oddly directionless, headless. The limits of this body, of its subjectivity, are impossible to determine—into what category of being do we inscribe it? Is it a simulacrum of a person? If so, is it merely a fragment, an idea of a person? Or is it, being of wet clay (no missing the Adamic significance here; the creation’s material indicating its status as creation) closer to the building in which its presented than it is to us, as viewers? Ms. Morrison’s work is purportedly “connecting the line between the body and earth”, but it’s also doing more than that: it’s expanding the subjective relationships to art and opening up multiple potential significations for the body—and, by extrapolation, the subject, the viewer and the work.

Daniel Lichtman, Do It Yrself, 2010. Via Scaramouche

As you move toward the back of the gallery (provided you’ve taken my itinerary), you become aware of an arrhythmic, ominous thumping—like a frightening clothes-dryer with sneakers in it. It’s coming, even more unnervingly, from behind a black curtain. Perhaps I’m easily suggestible, but it took me a moment to get up my courage to peek behind the curtain. The simple combination of unidentifiable but ‘dark’ sound and drawn, dark curtain, pull one into an experience of anxiety before one even engages with the work. This highlights the relation between all the pieces, for the installation quietly reaches beyond its own space to interact aurally with everything else in the space. It’s effective and affecting—and particularly interesting once one actually enters the installation. Here, figures slowly move in an arc, holding tree branches aloft, across a video screen. It’s as though they are riding on a wheel and we are catching them at the top of their orbit, a rather unsettling position that suggests that much is going on around and below and behind the frame. Really though, the tree branches moving silently, menacingly, inexorably forward recall nothing so much as Malcolm, Macduff and the Earl of Northumberland marching on Macbeth’s Dunsinane, hidden by the branches of Birnam Wood. I love this image—it’s creepy and menacing and beautiful and familiar all at once. It’s also, seen from the side, and on video, and through the screen of allusion, a masterful exercise in the sort of framing and re-framing, unframing and re-fashioning, or, finally, outright refusal of boundaries that characterizes the whole show. It’s a rare curatorial effort that can take such a delicate web of interactions and, without crushing it, impose a consistent vision, and Erin Sickler has done an admirable job. The title makes one wonder—is there another level of relation here, an Anglo-American joke in naming itself after our motto?

]]>

Isabel Pavão, Brooklyn Bridge Series, 1999-2000. via Rooster

Rooster is a charming little gallery, barely two weeks old, on that strip of Orchard street just below Houston that still occasionally shows up in writing as the “new” locus of hip young art, heroically opposing the boom-driven, testosterone-inflected, big-money jackhammer of the Chelsea and Meatpacking districts. (57th Street seems barely to warrant a mention these days.) I am generally suspicious of such binaries, but I suppose Rooster may in fact be what it wants to be seen as, a place where, as one writer has it, “as happened in the seventies, and after the early-eighties crash, and again after the early nineties crash, a new crop of creative entrepreneurs are entering the scene.” In New York we see mini-movements everywhere. Locked within a post-Warholian economy that turns less on the metaphysical identification of the current, fifteen minute thing than on the slow movement of such claims across magazines, blogs, journals and suitably loosened lips, we find the scene has become spatial as well as temporal. In contemporary New York, every person or place will be famous for fifteen minutes at fifteen different moments in fifteen different discursive spaces.

So whether what is going on in the Bowery/LES is an actual, social-artistic “movement,” the soi-disant natural pattern of gentrification, just starting, already over, distinctly commercial, categorically resistant or some combination thereof depends entirely on what card you carry and which internet you read. And, of course, everybody is right. The only real inevitability is a historical comparison with the ever more mythic past, a trope on which business-savvy gallery owners have never failed to capitalize.

Carlos Roque, Give Me Your Best Shot 3, 2009. via Rooster

Leaving aside any art-scene contextualizing, Rooster’s current, and inaugural, exhibition, Geography of Affection: 6 Portuguese Artists in New York is carefully curated, and, though uneven, quite effective. It’s a mixed-media show, letting each artist shine while still maintaining a chaotic unity. This is highlighted by the gallery space itself—the first floor is Lower East Side white-box-tiny, and half of the show is located in the basement down a vertiginous, if Lilliputian, spiral staircase. The geography of the title is not incidental—the gallery owners have found a solid niche with their intention to “organize an annual exhibition of new Portuguese artists, who….decided to make this city their own.” Parallel to this runs the assertion that “in new geographies, affection measures the distance.” This location-based affect of relation is compelling, especially in the context of New York, where so many streams merge in and out of one another. Focusing on one of these- the Portuguese origin, in this case – the exhibition elicits a precise emotional response, tracing out the timbre of a geographically bracketed nostalgia (or, more apropos, a saudades).

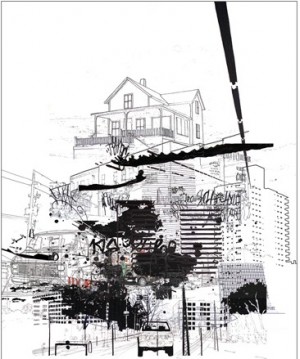

This is complemented by the diversity of genre and medium, both between the works and within them. Carlos Roque’s digital print Mundo Moderno no. 2 is a good example of this confluence: a jumble of precise, draftsman-like drawing, overlaid with varieties of text—graffiti-style, signage, and so forth—presented in both anterior and mirror image, so you’re never quite sure of how deep the work wants to take you, dimensionally speaking. Sharp lines thrusting at various angles through the frame, and variously scaled vehicles add a dimension of movement, and thus, also, of time, to the assemblage of directions. It’s like crossing Houston Street—seemingly a straightforward proposition, but in actuality a jumble of direction and movement that undermines any fixed perspective. Its strengths are those of the exhibition as a whole—an engagement with depth, form and genre that is ultimately as playful as it is sentimental (French inflection, having to do with deep feeling, rather than the English, maudlin).

Teresea Henriques, Anxiety, 2010. via Rooster

More delicate, though no less effective, is Isabel Pavão’s Brooklyn Bridge Series. The postcard image captures the bridge, in an epically-scaled and -angled sweep, from below, playing with its iconography. The bridge’s monumental span and ironclad iconography are softened by an overlay of whites, blacks and warm grays (with a very few Pollockesque drips), and framed by text that reads, “NEW YORK CITY the brooklyn bridge.” The three photographs aren’t measurably different (I don’t think), but something about the variation in tonalities of gray splashed across it makes each image emotionally unique. It feels like the same image seen three times through the same camera on a rainy day at three minute intervals. Again, the sense of space is displaced by an engagement with mixed media, and, in this case, by the sly use of text as frame-within-frame, which remakes a postcard, the tangible incarnation of an outsider’s place-memory, into an object of commentary, before finally transforming it into something else entirely.

Directly opposite the Brooklyn Bridge Series in its position in the gallery is Teresa Henriques’ installation Cynicism/Anxiety. While its sculptural shaping, simplicity and intimate scale are beautiful, and instantly put me in mind of Man Ray’s Object to be Destroyed / Indestructible Object series, the best thing about the work is its sound. It makes a sort of gentle whirring that is surprisingly suggestive, forcing our engagement across multiple sensory levels, without being aggressive, only strangely, soothingly, imperturbable. This soft quality, which invites emotion without bullying the viewer into a response, is what characterizes Geography of Affection: it’s evocative without being manipulative, earnest without being trite. To be sure, some pieces are less successful than others, and some don’t particularly work as parts added to the sum of the show, but the exhibition is solid enough to withstand this, calmly whirring along.

]]>

Robert Capa, Exiled Republicans being marched on the beach from one internment camp, Le Barcarès, France, March 1939. via ICP

The photographic negative is a pregnant subject and a loaded object. It holds an infinite amount of potential— each negative, in its development process, can yield countless, physical entities that will, in turn, go on to live their own stories. The Mexican Suitcase at ICP traces the journey of some very specific negatives along this imagined path, creating an emotionally loaded and symbolically fraught historiography.

The Mexican Suitcase is in large part the story of a series of objects and memories nestled within each other like Russian dolls. According to the ICP, “In late December 2007, three small cardboard boxes arrived at the International Center of Photography from Mexico City after a long and mysterious journey. These tattered boxes—the so-called Mexican Suitcase—contained the legendary Spanish Civil War negatives of Robert Capa. […]Together, these roles of film constitute an inestimable record of photographic innovation and war photography, but also of the great political struggle to determine the course of Spanish history and to turn back the expansion of global fascism.”

Gerda Taro, Republican soldier on a motorcycle, Navacerrada Pass, Segovia front, Spain, late May–early June 1937. via ICP

This collection of negatives has acquired a mythology of its own even as it relates to such a massive historical thread of the twentieth century. Its particular, peculiar, spottily-detailed journey is compelling and evocative; it is also part of the persistent popularity of narratives around lost artworks (as in the recent discovery of a masterpiece in a sealed Paris apartment or the popular book and documentary The Rape of Europa). Art-inflected mysteries may be so exciting because art is itself mysterious, and The Mexican Suitcase adds both formal and paratextual layers to this fascination. Formally, we are intrigued by the unknown quantity that is the negative image; historically (not that it’s a contest, of course), it’s hard to top the Spanish Civil War for drama, pathos, and horrifying consequences. The Rape of Europa was doubly compelling because it added the massive Nazi art thefts – and the personal histories of those individuals intimately connected to them – to the stories of the works themselves as well as the greater narrative of the War. Here, in recovering images of the Spanish Civil War, these negatives become new fragments of a contested past, and bringing them to light (no pun intended) has all the excitement of unwrapping a hidden piece of history.

The ICP has done an admirable job of presenting these images with equal parts intelligence and sensitivity as the details testify to a great deal of careful thinking. Many of the negatives, for instance, are simply tacked to the wall, unframed. This not only creates a sense of intimacy by removing many of the presentational flourishes and divisive objects (like frames) that are commonly accepted intrusions in the presentation of 2-dimensional artworks, but it quietly makes an eloquent case for the tactile experience of the photographic object, precisely when it has lost much of its ground, probably permanently, to the digital image. For my generation, media coverage of the war in Iraq has defined how we perceive visual war reportage. Much ink has been spilled on the distancing immediacy of experiencing a war on TV—those real-time, night-vision images of the bombing of Baghdad in March 2003 were simultaneously much more “accurate” and much more remote than physical wartime photos. When the twin towers fell, more than one person commented that it looked like the film Independence Day. This is not to say the digital image is not as rich and as full of possibility as the film photo, but to point out how this way of seeing has, in a sense, flattened the emotional topography of our relationship to war reportage.

Chim (David Seymour), Two Republican soldiers carrying a crucifix, Madrid, October– November 1936. via ICP

Here there are at least twenty negatives dedicated to a couple lunching in a plaza—with the woman out of the frame. The minute changes in the man’s facial expressions tell a complex story. Each negative could have yielded a different set of photos with its own physical life and a very different narrative. Very rarely does one take so many shots on the digital camera—the physical experience of clicking away, unaware of what shows up until the film is developed, has nearly ceased to exist, and we feel its loss here. One wonders which image the photographer would have chosen as the “right” one, the singular, defining image, had the photo’s journey not become a Borgesian garden of forking paths.

A further strength of The Mexican Suitcase is its organization according to a loose logic of theme and place. Some sections are called simply ‘Asturias’, ‘Madrid’, and so forth; others are titled ‘Refugees’ or ‘Basques’. These invite us to engage with multiple levels of the conflict, even as they echo the fractious, heterogeneity of Spain (of which the fascists were not particularly fond). Put another way, the curators have acknowledged the diverse, sometimes overlapping layers of identity: regional, spatial, cultural, contextual, historical, temporal. In fact the exhibition is a series of prisms that can be endlessly combined to present a multiplicity of thoughts and impressions. It’s a rare and perceptive kind of generosity that benefits both viewer and subject, while also giving due credit to the possibilities elicited by the work.

Robert Capa, Republican officer and Gerda Taro, University City, Madrid, February 1937. via ICP

The exhibition ultimately presents a series of layered losses: the catastrophic fall of Spain to Franco’s fascist government (which would remain in power until the mid-seventies), the loss of the negatives themselves, and, I think, the loss of our collective intimacy with the photographic image. Downstairs at ICP you can also see Cuba in Revolution, which has little-known images from both before and after 1959. It’s a very different war, in many ways, ad one that ostensibly evokes completely different sensations—but its juxtaposition with The Mexican Suitcase can hardly be coincidental.

]]>

Bernhard Fuchs, Weißer Passat (White Passat), Dusseldorf, 2004. Via Jack Hanley

Investing objects with individual desire is always a tricky proposition for the visual artist, if a conceptually enticing one. Portraits of inanimate objects assign an importance to what they represent, giving them a pathos not apparent with an incidental gaze. The significance of being chosen for representation transforms them — an operation that has become something of a platitude since Duchamp made it explicit in 1917 with the famously infamous Fountain. As the seminal promoter and photographer Stieglitz wrote in support of Duchamp-cum-Mutt, “Whether Mr Mutt made the fountain with his own hands or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object, “ While this is, of course, also one of the exciting transformational possibilities of the camera, it does gets dicey fairly quickly. Perhaps the inherent contradictions, tensions and presumptions in what amounts to a portrait series of abandoned objects accounts for the vague but identifiable annoyance that is Bernhard Fuchs’ show, Autos, on display at the Jack Hanley gallery in Tribeca through 3 October.

Bernhard Fuchs, Autos, installation view, 2010. Via Jack Hanley

Mr. Fuchs tells us the work is inspired by bicycle trips, during which “time and again, I saw passenger cars, buses, and trucks which just stood around. I think my first reaction was o [sic] look for the absent owners. Since I hardly ever saw anyone, I stayed alone with the situation, and a relationship to these vehicles began to develop as I would not have expected it. The car in the landscape had an impact on me, similar to the impact of actors on a stage, and since then I began to collect their wit and their tragedy.” The idea of this collection as a collection is interesting and troubling. It’s interesting, if not terribly original, to consider how objects are transformed by our relationship to them, by the privileged stature that is conferred by the act of being collected. Suddenly, because Mr. Fuchs has chosen to photograph them (and, then, because a gallery has chosen to display those photos), the vehicles become meaningful; because this meaning derives from Mr. Fuchs’ choice in representing them – and because he encountered them on an alternate mode of transportation – he is inscribing them with an emotional and aesthetic value he has determined. There is a disconnect in these photos between the ‘tragedy and wit’ Mr. Fuchs wants us to read in the images, and, at least for this viewer, the independent emotional response. I was not particularly moved by any of the vehicles—in fact, they all looked pretty much the same to me, and, while I think this may be the point (each of these is, initially, unremarkable), it also creates problems that I’m not certain the photos themselves are strong enough to overcome. Mr. Fuchs wants us to do a lot of the work here; for the exhibition to be successful, the viewer must be willing to re-perform his action of forming an intellectual perception and an emotional attachment. This attachment is necessary to individuate the vehicles from each other, but the photos do not convey enough to invite that extra step.

Part of the trouble is that, in choosing to focus so exclusively on such a specific set of images, Fuchs leaves a lot of questions, probably too many, open to the viewers. The vehicles are all proportioned similarly in the frame and most lack much of anything of interest surrounding them. We are quickly drawn away from what Fuchs has told us he wants us to see, and to other, perhaps more formalist concerns. The specificity and exclusivity of Fuchs’ focus, and the repetitive nature of the photographs, makes everything in the images that is not the autos really count. This works both in Fuchs’ favor, by allowing to us to see his practiced confidence and fine sensibility for light, but also against him, as the composition appears trite under the scrutiny. In photo after photo, we have a car (usually a vaguely 1990’s, nondescript model with a boxy frame, trapezoidal angles and the surprising colors Americans associate with European cars), sitting in a wooded area, or near a highway, or, alone in a parking lot. In pictures like Weißer Fiat-Bus (White Fiat Van), and Grüner VW-Transporte there is a regrettable surfeit of what I always think of as ‘serious-memory-light,’ a sort of aggressively mellow, late-afternoon-inflected, golden tone that is just desperate to be described as “evocative” but comes across as intensely maudlin. This sentimentalizing tendency is evident in other heavy-handed touches: the repeated use of a grey-on-grey theme, the mists, the path-heading-into-mysterious-woods motif, the way the gaze lingers on the beginnings of rust around a window frame.

Bernhard Fuchs, Weißer Fiat-Bus (White Fiat Van), Dusseldorf, 2004. Via Jack Hanley

The “moment of the ‘happened upon’”, as the gallery has it, is a potentially rich one, as is the metaphor of the random, motionless vehicle, but the photographs, on the whole, are too flat to elicit an independent identity. Any feelings of “wit and tragedy” belong solely to Mr. Fuchs, not to the objects he seems to wish were possessed of grander significance than they are. I’ll happily grant that if we look long enough, we can invest anything with meaning. That, as Stieglitz recognized, is how art works: once it’s presented as such, we can make ourselves experience it artistically. But the fact that we can find meaning in Mr. Fuchs’ images, if forced to, is more a testament to the imagination than his power to excite it.

]]>