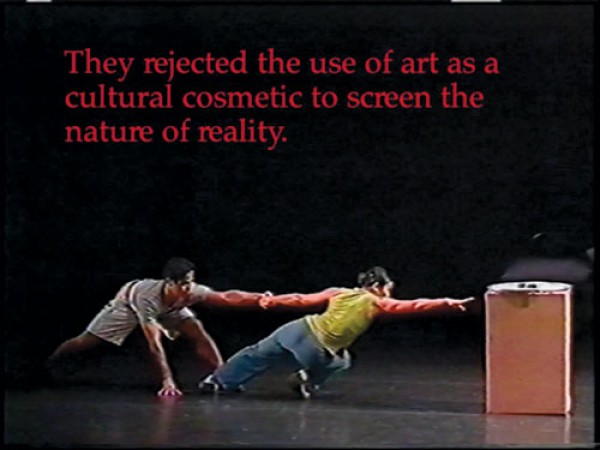

Yvonne Rainer, AG Indexical, 2007. Via artcalendr

Amidst a slew of recent literature seeking to historicize or otherwise situate the practice of dancer, choreographer, and film-maker Yvonne Rainer, Catherine Morris noted one irreducible ‘conventionality’ of Rainer’s oeuvre: her devotion to performance as a form of display. “The performance is always performing” – and to an audience of spectators, no less. Significant for an artist often associated with the radically democratic pretensions of a certain postmodernism, Rainer’s conception of engagement bears no trace of that peculiar element of interactionism recently lauded as “participation.”

Rainer’s preferred form of spectatorship recalls the captivated audience of cinema, making her shifts between media and live performance relatively fluid. Hers is an aesthetic openness that finds expression in direction, be it that of the body’s motion or the progressive sequences of film. Thus her most recent works about and/or featuring dance can be staged live or screened as cinema, not because of any ritualized documentation procedure, but because the alchemy of the audience/performer relationship remains consistent. After all, video is often used to learn choreography; one of the dancers in AG Indexical with a little help from H.M. (2007) attempts to mime the steps in a passage from George Balanchine’s Agon (1957) by rolling out a TV screen and watching a clip play back on VCR. The audience observes her pantomime but sees only the backside of the monitor. Despite Rainer’s ‘re-vision’ of choreography here and elsewhere, her work is deeply informed by the history of dance (which, in this case, the audience does not actually rewatch in situ). Four decades on, as Morris writes, Rainer still maintains an “ambitious drive to dissect historical conventions of performance.” Together with Simone Forti and Trisha Brown and under the influence of Anna Halprin and Merce Cunningham, among others, Rainer pushed the limits of dance past Martha Graham’s modernism, thoroughly changing the spectator’s expectations for performance.

George Balanchine, Agon, 1957. Via The Winger.

Two exhibitions at Southbank Centre in London, stretching from the autumn season, present extremely different representations of Rainer’s work, particularly in regards to the relationship between dancer and audience. The Yvonne Rainer Project at the British Film Institute explores Rainer’s works on film. In addition to feature-length films Lives of Performers (1972) and Film About a Woman Who… (1974), both intended for conventional screening, an installation in the BFI foyer galleries presents a library of Rainer’s most-plumbed theoretical and literary sources. Three relatively recent works, each originally staged live at Documenta 12, Performa 2007 and elsewhere here take the shape of video art. AG Indexical and RoS Indexical (2008), both filmed by Babette Mangolte, riff on the formalism of Balanchine’s aforementioned Agon and Vaslav Nijinsky’s frenetic footwork for the fabled Rite of Spring, respectively. The same four dancers, variously trained and ranging in age from 30 to 60, appear in both pieces, which introduce parody, anachronistic music (Henri Mancini’s Pink Panther theme in AG Indexical, for example) and more or less mundane costumes. Rainer’s treatment of the canon is plucky and humorous, but never disrespectful; she describes her reworking as “pedagogical vaudeville,” which toys with the motions of the dancers as much as with the choreographies’ cult mythology. The reception Stravinsky’s 1913 ballet received in Paris (chaos, outrage) is unlikely today, with the the largest consuming demographic preferring to storm outrageously, if not in outrage, at events such as the opening of the Kardashian’s Soho boutique. There seems an implicit lament in Rainer’s mocking of the Rite of Spring legend, one which perhaps belies a nostalgia for the monumental impact of the historical avant-gardes. What would it take to elicit such an emotional response from a dance premiere today?

Yvonne Rainer, RoS Indexical, 2007. Via hicns' flickr

Across from the BFI at the Hayward Gallery, Move: Choreographing You has been plying its experiential interactivity on the public since approximately mid-October. Iconic sculptures by Lygia Clark and Bruce Nauman, a new nine-screen video installation by Isaac Julian (Ten Thousand Waves, 2010) and a number of other works address the movement of the body in, through and around space – often neglecting duration in favor of participatory engagement (wall labels plastered near static objects encourage one to “please ask a dancer to activate this piece for you”). A handful of dancers wander by, performing, on the weekends, recent choreography by Xavier Le Roy and Mårten Spångberg as well as historic works, including Rainer’s Trio A. This had led to encounters such as on a recent Saturday when, as two dancers performed Rainer’s choreography asynchronously, a number of nearby visitors casually handled the hula-hoops stacked in the corner of the room (props for a Christian Jankowski installation). Prospective members of an “audience” treated the two dancers, whose movements went unexplained by wall text, with the deference typically afforded a Tino Sehgal: a sidelong glance and wide perimeter. The difficulty of Trio A lies in its lack of phrasing, its repetition and the stamina required to pile motion on top of motion on top of motion. The ‘reconstruction’ of Rainer’s piece at the Hayward, lumped together with so many other “interdisciplinary” works – so-called because of their difficult materiality as much as any relation to the viewer – was perplexingly banal. Its intricacy went almost entirely unrecognized. For the informed it may have been delightful to watch Trio A wind its way around the striated concrete of a Brutalist staircase, but for those unaware of the vitrine of source documents encased in the BFI galleries across the way, there was far too little access. Apart from recognizing the motions of Rainer’s work, any understanding of Trio A’s historical significance would be difficult to grasp.

If Rainer’s treatment of the archive plays with the historicity of dance without stripping away that history entirely, shouldn’t activations of her early work make similar considerations? The Hayward exhibition, foregoing a proscenium stage in order to confront viewers with choreography more directly, destroys the relationship between viewer and dancer altogether by denying both distance and duration.

Yvonne Rainer, After Many a Summer Dies the Swan: Hybrid, 2002. Via Artinfo.

Rainer’s final video work at BFI, After Many a Summer Dies the Swan: Hybrid (2002) locates the viewer in a cyclorama of Benjaminian textual montage and fragments of documented choreography. As a warning against the aestheticized decadence of Fin-de-Siecle Vienna – when “the life of art became a substitute for a life of action” – the work forms a strangely appropriate critique of today’s rampant exhibitionism, which trades conventions of ‘display’ for experiences of the spectacular. Perhaps a-historical relational stimulation is a poor format for conceptual work that demands one’s full attention. Or maybe the transition from the postmodern to the contemporary is not fully analogous to its predecessor; the postmodern novel, performance or work of art insisted on the coherence of form, if only to set off the radicality of content. The contemporary, by contrast, seeking an uneasy interdisciplinarity, dispenses with both, often confusing the comprehension of each. The more Rainer’s work, delicate for all its dense dance intelligence, is divorced from its intended setting and re-animated for contemporary purposes, the less likely it may be to eventually (in her words) “shake us out of complacency and comfort.” Postmodernism may simply be a victim of its own success, in this respect, but for Yvonne Rainer this can feel less like victory than defeat.

]]>

A demonstrator at Tate Britain. Via

The Turner Prize – that most infamous of awards – is named for the Romantic landscape painter J.M.W. Turner, who once expressed a desire to establish a fund for controversial young artists. In 1984, a group calling itself ‘Patrons of New Art’ remembered him when developing a scheme to support contemporary British art with new purchases for the Tate Gallery, creating the prize that bears his name. Its prestige accompanied by a cash payment of twenty-five thousand pounds, the award requires only that its winner be under fifty, be British (or working in Britain), and to have staged a solo show in the UK within the past twelve months. As the most substantial art prize in the country, it places the recipient center stage overnight, vaunting him or her, but usually him, into the esteemed (and internationally recognized) company of Gilbert & George, Rachel Whiteread, Mark Wallinger, and Grayson Perry. Meanwhile, the mystically undemocratic selection-by-jury-of-experts has inspired dissent from alternative arts groups critical of its byzantine machinations.

In other words, the Turner creates a high degree of visibility beyond the usual concentric artworld circles. This attention is amplified by the UK’s notorious celebrity-industrial complex, which places as much emphasis on producing fame as it does on dressing it down. Chris Ofili’s No Woman No Cry, (1998), Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991) and Tracey Emin’s terribly messy My Bed (1999) were all shown in the official exhibition of short-listed candidates, with both Ofili and Hirst going on to win. Held annually in the pristine halls of the Tate, and often received with spectacular consternation and varying degrees of antipathy, these shows have cemented the Prize’s reputation as an annual view – in the style of Turner – of the British (contemporary art) landscape.

The Nominees

Dexter Dalwood, The Death of David Kelly, 2008. Via

Dexter Dalwood

Born in Bristol, Dalwood is a collage artist working primarily with oil and canvas. That is to say, his scenic imagery is lifted from art-historical, pop cultural, and more recently political sources (The Death of David Kelly), resulting in a queasy postmodern mish-mash that is left figuratively – and sometimes pictorially – unresolved (the absent protagonist, the suddenly ruptured spatial ground) in precisely the ways that painting once sought to overcome. If Dalwood transgresses this technical effort he does so while remaining firmly within representation, in a style rife with “culturally interesting” image quotation. The bedrooms of Jimi Hendrix, Michael Jackson, and Bill Gates perform as tantalizing subjects imagined in unvarying bright colors, spackled over here and there with Cubist or AbEx touches and even clearly recognizable signatures—for instance, a retaining wall that mimics Jasper John’s White Flag . His flattening, even overdetermined, treatment feels ill-suited to painting—reviving all sorts of neatly fictionalized history but not the genre’s urgency.

The Otolith Group

Gods and heroes will seek asylum in art collections like political refugees in foreign embassies. —Chris Marker

Anjalika Sagar and Kodwo Eshun (who lectures at Goldsmiths) are hip to both geopolitics and the hyper-intellectualized lingo of the academic Left, considering their collective output to be Marker’s postcolonial heir-apparent.

Their film-essay Otolith III provides a speculative contemporary setting cut together with old Bollywood footage, which exhumes The Alien (1967), an unrealized film by Indian director Satyajit Ray about a small Bengali boy who encounters a kind extraterrestrial—a non-narrative narrative coyly toying with the meta-narrative of cinematic history. The duo’s explorations of microgravity as the loss of ground, orientation, balance, and stability that developmentally impacts the otoliths of the inner ear are often enchanting, more often pedantic, but always come fully equipped with theoretical armature eschewing any need for further commentary:

To turn away from monofocal visions of gravity towards complex narratives that embed agravic time-space within multiple notions of time, space and event necessitates a much more sophisticated approach towards the moving image. – Eshun, A Long Time Between Suns

Angela de la Cruz installation at Tate Britain, Via

Angela de la Cruz

The Spanish-born de la Cruz trained at the Slade as a sculptor, although she has been classified in her Turner cohort as one of (an astonishing) two painters. In fact she is a sculptor who can’t stop painting, then sacrilegiously pushing, pulling, crumpling, re-stretching and finally tearing the canvas and wooden frames of her monochromatic pictures completely apart and then wrapping, folding, warping and bolting them back together again. In the materiality of three dimensions (mass, volume, form), de la Cruz cleverly navigates the problem of representation, producing curiously expressive, even neurotic objects that are as much about suffering and pain as they are “paintings behaving badly.” Whereas a dirty white Homeless shrinks ashamedly into a corner, Still Life (Table) contains all of the objects painstakingly arranged on the table top and the table too; a pinched form with protruding wooden legs engulfed by shiny black canvas. For de la Cruz, painting may be “over” but its semiotics must still be reckoned with. Her (de)constructions, if irresolute, are unapologetically feminine.

Susan Philipsz

Born in Glasgow but now based in Berlin, Philipsz studied sculpture (at Dundee) and afterward turned to sound. For Filter she crooned a cover version of Radiohead’s “Airbag,” unaccompanied, into the PA system at a Tesco supermarket. Her Turner Prize-nominated piece featured an arrangement of the 16th-Century Scottish lament “Lowlands Away” — describing a lover drowned at sea — which reverberated beneath three bridges spanning the River Clyde during the Glasgow International Festival of Visual Art. Transported to an empty room at the Tate, Philipsz’s installation was certainly tranquilized for easy listening – although the hollow contemporary setting renders the textured historical ballad somehow more mournful. Playing asynchronously from triangulated speakers set low against the gallery walls, it composes a collective soundscape in which the ever-ubiquitous headphones are finally unnecessary. Philipsz considers the ways in which sound defines architecture, making the full character of its spaces available to our experience; a simple enough premise nevertheless alien to listeners, who clustered near to the wall text before branching further into the room.

Winner

Philipsz accepted the Turner Prize from Miuccia Prada on Tuesday evening— the first sound artist and fourth woman to win the award. The disgruntled complained that a visual art award had been given away for a song.

Loser(s)

Leading up to Thursday’s scheduled Parliamentary vote on the plan to triple University fees across England, some 200 students occupied the entrance hall of Tate Britain to capitalize on the media turnout. This was the latest in a series of continued protests against the coalition government’s proposed cuts to arts and education. Divided from the assembled prize audience by a temporary barricade, the students almost drowned out the presentation of Philipsz’s award.

Susan Philipsz sound installation at the Tate, via

Tate director Sir Nicholas Serota remarked encouragingly on their presence noting that “art schools have been laboratories for the kind of work that has gone on to win the Turner prize” and The Otolith Group’s Anjalika Sagar tailored her acceptance speech into a semi-provocative statement of support for the students whose brittle welfare state shattered so easily. Can a winter of discontent be waged effectively by immaterial laborers in an information age? At this point, and from this perspective, the landscape for those artists below forty appears puzzling, savage, and dramatically bleak.

]]>