that it is unlikely to be very long until the whole

lot bursts apart. -Siegfried Kracauer

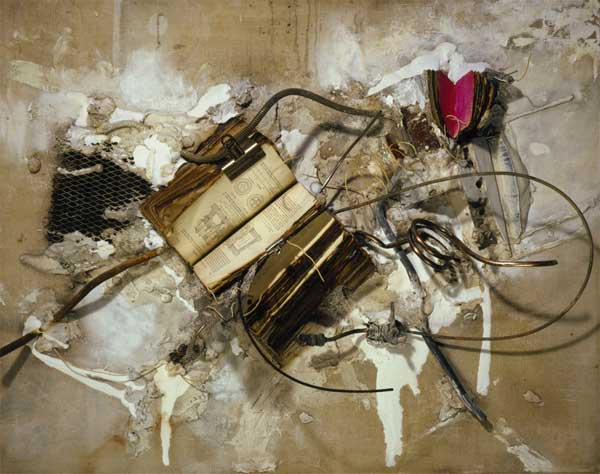

Otto Dix, Lustmord, 1922 via wgn.net

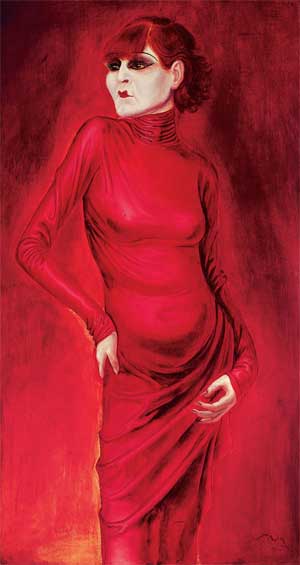

A glistening blaze of scarlet and carmine oils, Otto Dix’s Portrait of the Dancer Anita Berber (1925) is, according to Olaf Peter, curator of the first American Dix retrospective, “without a doubt the icon of the Weimar Republic.” Though one would not guess it from her aged appearance, Berber was twenty-six at the time Dix painted her, a bisexual prostitute and cabaret dancer who mixed with both high and low, famed for her proclivity towards nudity, cocaine, and excess. Pallid and consumptive, Dix’s Berber is at once sickly and sultry in a skin-tight crimson dress set against an empyreal wash of blood-red. She would be dead in three years, with the Weimar Republic not far behind. In a sense, Berber is a figural portmanteau onto which Dix projects the mordant nihilistic German mindset. Ravaged by death and excess, Berber is a metaphor for Berlin, a colony degage laid amidst the ataraxic sounds of hot jazz, its people determined to forget their pains in a frenzied pursuit of the bacchanal.

Chosen to marquee this masterfully curated exhibition at the Neue Gallerie, this portrait that is so much about the Weimar era is perhaps more telling about Dix himself. Berber is but one of many women appearing throughout the show in varying states of vulnerability, sexual activity, and fecundity. Dix’s often violent, misogynistic representations are, for many, the most disturbing aspects of the artist’s oeuvre. Here the female exists for Dix simultaneously as a figure of lust and revulsion, reverence and disgust. In Dix’s Reclining Woman on Leopard Skin (1927), a solitary female figure lies upon a feral pelt, her body arranged in serpentine form. With the right claw-like hand extended slightly, feline-like eyes contemplate the observer, Dix perhaps, as the woman appears to calculate her next move. A menacing wolf lingers hungrily in the background, underlining the predatory theme. Here the figural woman may not be vulnerable or passive, but she is dangerous, a sexual siren to which man is sure to fall prey.

Otto Dix, Portrait of the Dancer Anita Berber, 1925 via mess.net

For the majority of the images here, however, women occupy spaces where erotic fulfillment is combined with violence and death. For Dix, sex was a carnal danse macabre, where mortality lay housed within the sordid, lustful rituals of copulation. Nowhere in the exhibition is this more apparent than in Dix’s small watercolor, Portrait of Lovers (1923), a vivid, frenetic scene in which a rotting, fetid female corpse straddles an emaciated, skeletal man. In this grim study, procreation does not beget new life, but rather as Fernando Pessoa claimed in his Book of Disquiet, a paradox where “[t]he dead are born” to the dying. In other, even more grotesque works, especially the Death and Resurrection (1922) series, the female sex becomes the object of a savage and murderous primitivism. One such image, titled Lustmord, translating literally as ‘sex murder,’ portrays a dead, prostrate female figure with her genitalia bloodily mutilated. The composition’s savagery is echoed in Dix’s heavy, expressionistic hand, effectively scarring the metal plates upon which the image is etched. The crime recorded by Dix is two-fold, the brutal slaying second only to the sex act itself. The cramped nature of the brothel room, combined with a distanced perspective and forensic manner, evoke a Weegee snapshot. That is until Dix injects his morbid humor into the mise en scene, adding two dogs mating in the corner of the image.

Women, or more appropriately, their anatomical capabilities, are represented in conjunction with a savage sense of mortality informed by Dix’s time as a soldier during the First World War. Indeed, one could argue that Dix’s representations of women are profoundly intertwined with the horrors of war. There are, for example, frequent references to prostitutes throughout Dix’s oeuvre, but some of the earliest of these appear in his Der Kreig (War) (1924) cycle of fifty etchings. In one such etching, Abandoned Prostitutes, gaudy, rouged women of the night parade on a darkened sidewalk turning tricks as a menacing soldier looms in the distance. Women can be seen throughout the suite as fleshy, carnal distractions to the surrounding war and carnage. Their ability for procreation, for creation, becomes bound up with the destruction of war and, as a result, women and sex become complicit in the totality of the war-experience.

Otto Dix, Dead Man - St Clement, 1924 via ottodix.org

And it is worth repeating how profoundly this war-experience informed Dix’s Weltanschauung. Influenced as much by Nietzsche’s will-to-power nihilism as by the hawkish manifestos of the Italian Futurists, Dix would volunteer to fight in the trenches of World War I. Saying, in a 1963 interview, of his desire to fight,

I had to experience how someone beside me suddenly falls over and is dead and the bullet has hit him squarely. I had to experience that quite directly…I have to experience all the ghastly, bottomless depths of life for myself.

A young machine-gunner on the frontline abattoir of the 1916 Somme Offensive, Dix experienced first-hand one of the bloodiest military operations in history, one costing close to 1.5 million casualties. In this topography of annihilation, the young artist would come to believe that “war, too, must be seen as natural phenomena.”

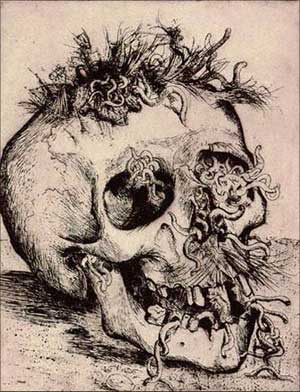

No doubt wishing to underscore the formative nature of Dix’s wartime experiences, curator Olaf Peter’s exhibits the War cycle in a separate room of the Galerie. Recalling Goya’s Disasters of War, Dix’s War is overwhelming to experience, as the artist quickly conjures the ambiance of the Western Front. From out of the velvety washes of black aquatint there emerge Bosch-like vistas scarred by artillery (Collapsed Trenches), images that evince the scent of acrid, leaden skies – a palpable mixture of metal upon winds tinged with the fetid stench of rotting corpses. There is, noted Paul Ferdinand Schmidt, the hand of “fanatical cold-bloodedness” at work in all these images. Indeed, Dix’s emotional stance appears to be neither detached nor wholly compassionate towards the blight surrounding him. A Dürer-esque smiling skull sprouting worms (Skull) is shown along with a study of rotting corpses (Dead Man – St. Clement), both rendered with a high degree of forensic exactitude. As curator Mark Henshaw would note in his catalog statement for the Austrian National Gallery, “Paradoxically, there is also a quality of sensuousness, an almost perverse delight in [Dix’s] rendering of horrific detail.” But beyond just a zealous interest in rendering, Dix himself took a perverse pleasure in the events unfolding around him. Olaf Peter relates how Dix would often appall his friends by providing a “detailed description of the pleasurable sensation to be had when bayoneting an enemy to death.”

Otto Dix, Skull, 1924, plate 31 from Der Krieg via cs.nga.gov.au

No doubt it was all of this together that lead Dix to identify with the burgeoning Neue Sachlichkeit movement. Attributed to a 1925 exhibition organized by G.F. Hartlaub, Neue Sachlichkeit, roughly translated as New Objectivity or Austerity, referred to the growing number of Weimar artists, Christian Schad and George Grosz included, who rejected the soulful, sentimental characteristics of Expressionism. These artists replaced these characteristics with biting, highly stylized representations of post-war Europe. Neue Sachlichkeit came to personify what historian William Robinson observed as the “depressed, neurotic spirit of the time.” While their work was not necessarily devoid of emotional content, members denounced empathy. Adopting established techniques of the Old Masters’, in combination with confrontational scenes, Neue Sachlichkeit sought to arouse in the viewer a distressing sense of banality and disillusionment.

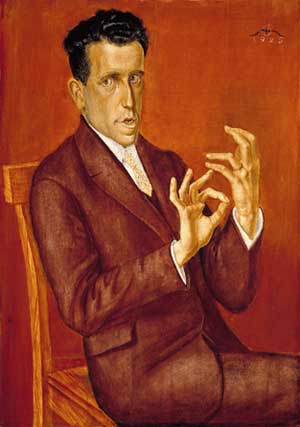

For his part, Dix readily drew inspiration from the Old Masters, especially Dürer, Lucas Cranach, and Hans Holbein as he combined a painstaking attention to detail with a Mannerist flair. Within the exhibition, images such as Portrait of the Poet Iwar von Lücken (1926), or Portrait of the Lawyer Dr.Hugo Simons (1925), present elongated, exaggerated bodies reminiscent of El Greco’s depictions of the Stations of the Cross. That Mannerism should have had such an impact on Dix is significant, for though it had occurred some 400 years prior, it dealt with many of the same issues confronting Neue Sachlichkeit . Largely in reaction to the harmonious, restrained naturalism of Renaissance artists, Mannerism was, as historian Arnold Hauser notes, “the expression of antagonism between the spiritualistic and sensualistic trends of the age.”

And yet, for all the similarities between the movements, the Mannerist art of the sixteenth century was largely an aristocratic movement, “the court style par-excellence.”

Otto Dix, Portrait of the Lawyer Dr. Hugo Simons, 1925 via antiquesandthearts.com

In 1928 Bertolt Brecht, along with Kurt Weil, staged his famous production of The Threepenny Opera at Berlin’s Theater am Schiffbauerdamm. Brecht attempted to discourage viewers from developing illusory narratives and unnecessary sympathies towards his characters by emotionally distancing the audience from the performance. This was his celebrated Verfremdungseffekt or “alienation effect.” Audiences required this distance, Brecht believed, in order to be able to reflect critically on what was being presented, as opposed to being taken out of themselves as in traditional entertainment.

Dix certainly suffered from his own Verfremdungseffekt of sorts, a state he projected onto his canvasses. Dix’s use of the Old Masters’ techniques in conjunction with spectral colors, biting satire and images of graphic savagery offers a portal into the mind of a man who found the uncanny in the familiar. Brecht’s Verfremdungseffekt teaches the viewer to practice just this sense of distance, carefully considering the style presented as itself highly constructed and dependent upon an imbricated web of cultural and economic factors. Read this way, Dix’s images allow us to observe a brief, but persistently fascinating period in history through the lens of his trademark, pathological intensity. Whether visualizing the macabre and glorified world of Weimar Berlin, or gathering fleeting glimpses of the unease submerged in everyday circumstances, Dix’ work remains an unflinching vision of “life without dilution.”

]]>

Jonah Bechtolt, NTSC-YA, via Thierry Goldberg

A recent visit to Thierry Goldberg Project’s small Lower East Side gallery reminded me of Donald Judd’s continuing and pervasive influence on a current crop of contemporary Neo-Minimalists. Rivington Street, however, is far from the arid, grassy plains of the Texas panhandle and whether Judd’s legacy is being faithfully upheld by the current Goldberg exhibition, Unspecific Objects, is a matter of debate. Taking as its curatorial starting-point Judd’s seminal essay from 1965, “Specific Objects,”, the Goldberg show can be viewed as a lesson in the many ways Judd’s writings have come to be interpreted amongst a contemporary set of curators and artists.

One could argue that Unspecific Objects, like so many recent shows referencing past vanguards, is simultaneously a retrospective of one individual’s conceptual legacy and a showcase for a new generation returning to and reworking that same heritage. One of the potential problems with this approach is that, located within such a specific conceptual/historical text, the works included open themselves to a level of dogmatic scrutiny that can undermine the artist’s intention. The viewer may find themselves primarily concerned with whether the exhibition is successful as organized and inspired by the writings of Donald Judd instead of examining the value of the works themselves.

It is certainly clear that Judd and his impact on Minimalism has influenced the exhibited works The real question is, do they constitute art that exists in accordance with Judd’s notion of the “specific object” while concomitantly reinventing or repositioning that concept? Or, is the Goldberg show yet another example of the popular, vulture-ike practice of taking certain elements from well-known texts and building whole shows from them, disregarding the literary carcass from which it came?

Written in the year after his first solo show at New York’s Green Gallery, “Specific Objects” was, as Charles Harrison observes, “noteworthy for its claim that the representative art of the modern is now neither painting nor sculpture but the virtual medium of ‘three-dimensional work’.” For Judd, a leading figure “of [that] apostate Modernism” which was to become Minimalism, the rejection of traditional artistic craftsmanship and expression infused work that broke ground exploring light, space, interval, and color. Directing his attention to volume and the presence of structures and the spaces around them, Judd made the viewer aware of the greater physical and psychic relationships between subject, object, and site.

Judd first coined the term “specific objects” in reference to structures that were neither paintings nor sculptures, but rather objects that existed liminally between the two. In the 1965 essay bearing Judd’s neologism as its title, we find a desire to transform the art-object into a self-sufficient creation and also to eliminate any factor interfering with the physical qualities of the art-object’s composite materials. Judd himself would claim, “[a] shape, a volume, a surface is something in itself.” Radically rethinking the Hegelian concept of artistic origination, Judd in essence argued for a new creative paradigm in which the artistic-object was created not through the alteration and synthesis of material, but in its temporal and spatial reinterpretation.

David Scanavino, Untitled (one square inch) via Thierry Goldberg

No artist in Unspecific Objects comes closer to realizing Judd’s “object” ethos than David Scanavino whose installation is located in the gallery’s back room. With Untitled (one square inch), the Goldberg gallery floor has been covered in black and white-flecked linoleum where, seemingly from beneath the menacing P.V.C. flooring, a small cube protrudes. From a specific point of view, the cube appears to melt into the floor, deliquescing into the site of its origin. In effect, Scanavino transforms the entire room into an object of contemplation, the black linoleum a psychic counterpoint to the walls and ceiling of the white cube. Scanavino’s installation becomes a total site, interfacing itself within a greater web of meaning extending beyond the work, physically expanding both the site and concept of it towards an “indefinable sum of a group of entities and references” (as Judd defined a “three-dimensional” work).

In contrast, Daniel Ellis’ SOSO Mint Green and SOSO Black/Black, as well as Rashawn Griffin’s The Haberdasher readily fall into a trap identified in “Specific Objects.” On two 36”x36” canvasses, Ellis repetitiously places the international Morse code distress signal (• • • — — — • • •), or SOS as it’s commonly known prosign, over both mono and dichromatic backgrounds. The conformity to traditional framing conventions, but also Ellis’ use of painting within established confines, wholly “determines and limits,” as Judd wrote in “Specific Objects,” “the arrangement of whatever is on or inside of it.”

Daniel Ellis, SOSO Mint Green and SOSO Black/Black via Thierry Goldberg

Perhaps as a reaction to Judd’s aversion towards a fixed planar form of painting, Griffin’s canvass is suspended from the gallery ceiling, the result of which makes both sides visible. One side of the 33”x46” canvass is fully covered in a gray argyle patterned fabric, with the reverse side the same but with an added small, loosely composed collage on top. The press release asserts that Griffin’s work, “free standing and sometimes suspended,” speaks to “the sculptural presence of painting.” However, let us be clear: this is not the three-dimensional work Judd was speaking of, and the facile explanation that, in suspending a canvass, such an effect is achieved, does Griffin and his work little justice.

For both Ellis and Griffin, the merits of their respective works are lost in their apparent inability to channel or re-invent the paradigms developed in “Specific Objects.” Thus, while Ellis’ work maybe a highly stimulating meditation on a system of valuation rooted in inherently meaningless and artificial symbology, when measured against the standard set by Judd for his essay, Ellis is unable to break free from the yoke of traditional European art. With Griffin, the attempt to engage in Judd’s 3-D concept of the “specific object,” fails because the image is not liberated from its rectangular frame, regardless of its suspension. As Judd noted, we all know that “anything on a surface has a space behind it.” Thus Griffin’s approach is too overtly literal. Rather than emancipating what is within the frame from its bonds, Griffin merely unhinges the frame from the wall, while the framed content continues to exist bounded, this time, however, rigid, fixed, floating in a predefined temporal space – anchored to the structure of the institution by metallic sinews.

That being said, while the frame of a painting confines the work physically, it need not deprive it of psychical depth and in that respect, Griffen is in harmony with Judd’s critical philosophy. With this in mind, there is, in Takayuki Kubota’s works, a greater exploration of depth within the bounded plane, one that does succeed in freeing the image from its material bonds. Kubota’s compositions may be confined by the same physical dimensions of the frame as are Ellis’, but Kubota’s explores a richer psychic plane with a virtuoso choice of medium. Three small frames house thin, horizontal lines of reflective material. At first glance, I was greeted by my reflection, bisected by multiple small lines, no doubt painstakingly applied. It turns out the medium is in fact magnetic tape used in the recording of atmospheric sound, first spliced and then adhered to the respective panels. One is not only viewing a reflection of themselves and their surrounding environment, but simultaneously observing the aural traces of a past event from a separate temporal site. Here the senses are brought into a collision that transcends classic modes of observation. The flat surfaces of Takakyuki’s images penetrate through to a depth beyond their material surface, existing at once as reflection and reproduction, sight and sound, physical materiality and aural depth. True to Judd, the material of the tape is left largely unaltered, free to imply via the juxtaposition of its indexical nature as record of past, mirror of present, and archive for the future.

Takayuki Kubota, Untitled via Thierry Goldberg

Martin Basher’s installation, Untitled, is most effective at examining the underpinnings of the physical and temporal realities inherent to the art object – realities that Judd examined throughout his career. With Untitled, a poster of a Manet landscape is affixed to a canvass on which is painted vertical bars of color, or to be more exact, the seven colors that make up the visible color spectrum. (One might fondly recall from middle school science classes the acronym for such colors as ROY-G-BIV.) Leaning against this all is a thin cylindrical tube of white fluorescent light. In sequential steps of glib reductionism, from the Monet to the canvas of spectral colors and finally to the monochromatic tube of light, Basher deconstructs the fundamental aspect of human optical perception, breaking down color to its most basic form – visible wavelengths of light. In drawing our attention to the dynamic nature of color, of its state as an oscillating refraction of light occupying a multi-dimensional space, Basher constructs a spatial locale that, like Kubota’s, extends beyond the planar dimensions of the canvass, interacting instead with the dense grid of our own system of visual perception.

Likewise examining color and perception, Jonah Bechtolt’s video installation, NTSC-YA, is a briefly animated loop in which a TV screen is incrementally filled with a test pattern only to have the same pattern withdrawn, accompanied by the sound of a respectively ascending and the descending monotone. The is simple, but, like Basher, it reminds the viewer of the basic and natural phenomena of color and perception. I would hazard to guess that the ascending and descending tones coincide with the wavelength frequency associated with the respective bars of color in the video. I am less inclined to believe, as the press release claims, that the work challenges the uniformity of Minimalisms and Colorfield Painting by “infusing it with a sense of play.” Rather, Bechtolt has appropriated the Colorfield Painting and brought it into the electronic age. The question here is not one of challenge, but assimilation or evolution via technology. The same basic colors of the visible electromagnetic spectrum are found in every painting throughout human history. The forms that derive out of those colors, in whatever period or stylistic era, all revolve around this fact, one that might have led Judd in “Specific Objects” to write “[a] painting by Newman is finally no simpler than one by Cezanne.”

“Specific Objects” ultimately concluded that, “[s]ince its range is so wide, three-dimensional work will probably divide into a number of forms.” Adding to that, “[a] work can be as powerful as it can be thought to be.” Reflecting upon the Thierry Goldberg exhibit, I think the works included have had their powers diminished. That is to say, Unspecific Objects‘ curatorial vision has the effect of curbing the works’ potential power, confining them to a narrow conceptual field requiring a greater level of scrutiny and expectation. The works included are each, in their own right, strong examples of artists working, knowingly or not, under a panoply of creative movements and influences, of which Donald Judd is surely one. In that sense, the exhibition succeeds as a survey of artists working submontane to the imprint of Judd’s Minimalism. However, most of the works in Unspecific Objects fail to live up to the prescriptive three-dimensional “Specific Object” of Judd’s essay. It is likely that the artists never set out to directly engage in a dialogue with Judd’s essay. Nor does their perceived failure by this standard really matter. After all, it was Judd himself who wrote, “[a] work needs only be interesting.” And in that regard, Unspecific Objects is interesting.

]]>

Meeting of Artists' Placement Group via the Tate

Upon entering the current exhibition at apexart, The Incidental Person, one could be forgiven for thinking that he or she has stepped into the offices of some fledgling political action group or non-profit museum dedicated to such causes. The walls are covered with oversized clippings of newsprint and witty slogans of subversion, colored streamers traverse the ceiling and there is a nimiety of wordy pamphlets, giving the overall appearance of revolutionary activity. Indeed, far from any pretense of being an exhibition either of art objects, The Incidental Person is simultaneously a retrospective of the now defunct, influential British Artist Placement Group (APG) and an examination of its legacy on a new generation of hopeful social provocateurs.

Founded by artist couple John Latham and Barbara Steveni in 1966, the APG was among a growing number of 1960’s practitioners who had come to expand upon the previous decade’s interest in “art and technology,” seeing in the two a potential for collaborative relationships between art and industry. For their part, the APG favored a notion that artists would have a far greater effect upon society by working from within the structures of industry, directly effecting systems of production and governance. Thus, the primary task of the APG in the late 60’s involved the placement of its members in various corporate and governmental positions throughout the United Kingdom.

More concerned with social services and the integration of “artists into a participatory role in business matters and decisions making,” the APG committed “to the making of no product, work or idea.” Indeed, this broader movement away from the art object was, at the time, in keeping with Conceptualism’s interest in dematerialization. Latham’s emphatic refusal to give either form or definition to the placement of art appeared as a direct confrontation and critique of a society obsessed with objects and products.

Rejecting not only the classical art object, Latham confronted the traditional perception of the artist as originator, as authorial innovator in the production of works. In one of his most important contributions to the theoretical underpinning of the APG, Latham developed what he referred to as “the incidental person.” A relational paradigm, Latham’s “incidental person” referred to the actions of an artist within the imbricate web of industry, where their impact could be felt and charted over an extended period. Understanding this greater plurality of production roles, the artist was able to transcend any particular sense of individuation and was instead able to identify with a whole host of positions within the web of art making.

And yet, the APG’s true radicalism can be found within the very paradoxes, and potential faults, that lie at the heart of their attempts to reconcile what was both a structural and a theoretical model. Latham’s “incidental person” was at odds with Steveni’s desire to place the artist within various corporate and governmental capacities. For Latham, the artist was to be only one member in a vast network of individuals involved in the process of production, no more or less important than his fellow colleagues. Steveni, however, relied quite deliberately on an outsized view of the artists’ role in contemporary society, privileging the creative vision over others.

That the APG was more interested in social services than in any classically straightforward artistic product was a source of criticism. In an essay written in 1976 for Art-Language, a leading British journal “devoted to dissections of statements about art”, one critic observed that, “artists merely ‘realizing their socialization’ are just people pursuing the pathology of scandal…[for] ideological speculation becomes ideological action only when it generates class conflict and invests in class struggle.” While the extent to which APG’s goals coincided with those of the class struggle more generally is unclear, the fundamental questioning remains valid. With this in mind, we find the apexart exhibition taking its name, and curatorial onus, from Latham’s The Incidental Person in an attempt to account for the APG’s legacy while simultaneously positioning the works of a new generation as successors to the cause. Whether or not the artists exhibited are as successful is still a question to be answered.

John Latham, Philosophy and the Practice of, 1960 via PS1

In his article for Frieze magazine on the APG, Peter Eleely noted, “of the variety of projects from the last decade or so that have mimicked or inhabited corporate models while also making participation and collaboration” an integral aspect of their process, “Few have achieved APG’s delicately Utopian co-existence of antagonism and service.” In many of the works exhibited here, it is that necessary combination — of service and antagonism — that is least apparent. For her performance, Funds Show, Gianni Motti videotaped herself throwing $6,400 from the balcony overhanging the space in which she was exhibiting. While the commentary on the value and interchange of money is clear, one is left to ponder if the antagonism of a work doesn’t vanish when the actions of the artist are pre-recorded, if a truly peformative element would have been more effective. Here the viewer is left to observe a record of Motti’s performance without any recourse for dialogue or exchange. Other works, including Ariana Jacob’s Documentation of Conversation Station, encourage a more direct interaction with the viewer and thus create a very tangible sense of antagonism. A chalkboard that has “People Die: Let’s Talk About It,” written on it in playful script prompts readers to gather and discuss a topic considered serious. That the results may not necessarily be quantifiable is of little matter, but the work no doubt engenders questions of mortality amongst its viewers. For Jen Delos Reyes’ installation, People Never Notice Anything, the viewer is invited to note observations and thoughts using pencil and paper provided to them. At the end of the exhibition, a group of individuals will be asked to give presentations at the gallery on the recordings left behind. Reyes effectively incorporates the viewer into the creative process and, in so doing, is probably one of the more successful engagements with Latham’s original concept.

Other artists in the exhibition seem far less concerned with the actual motives of the APG, operating instead within modified versions of the group’s original methodologies. Antagonism in such works often emerges from the artists’ attempts to reconcile conflicting beliefs about the traditional art object and their instructional value. Ron Bernstein’s Slide Archive, a compilation of twenty years of travels by the artist’s parents, is one of the more notable works in this respect. Here the images are projected into the gallery space, effectively transforming a public locale into a site of intimate reflection; nostalgia, dislocation and familial reverie cycle through the viewers’ mind, combining the banausic rotation of the slide projector with the pleasures of psychic reminiscences. Keiko Sei’s Video Archive is a compelling series of documentaries highlighting the oppression of Burmese dissidents at the hands of a series of repressive leaders. Like Bernstein, Sei’s videos are a thoughtful meditation on the boundaries between document and art object. Others, however, get caught up in the archival aspect of the work, losing themselves and message within the materiality of their works. In Constance Hockaday’s An Incomplete History of Rafts, the archival leans more towards visual hoarding. Hockaday’s mural of reproduced texts and hand illustrations does less to inform the viewer than to promote a sense both of inundation and informational superfluousness.

For some, it appears that Latham’s interest in the incidental gives license to engage and participate in cross-disciplinary activities, often with a result, however, that is more pataphysics than science. Rapahele Bidault-Waddington’s installation, The Polygon Project at LIID® (Laboritoire d’Ingenierie d’Idess), a walled-off area in which individuals are invited to brainstorm on a variety of esoteric topics, is more likely to illicit frustration with its incomprehensible charts illustrating various aspects of human entropy and thermodynamics.

For others, the interest in commerce and production, a key aspect of APG’s program, informs quasi critiques of the interlocking relationships of art and commerce. The effect, in many cases is more likely to be comical than antagonistic. As its title informs, Art and Beer, serves to unite the two in a result that makes the most vigorous hangover look preferable. Broaching the artist as capitalist, and vice versa, Eric Steen asked Portland micro-brewers to visit a local museum and locate works of art that may be sources of inspiration for new specialty brews. In one of the more memorable wall texts, a brewer notes, “the color, depth, and texture [of said painting]…reminded me of the swirling head on a pint of well poured nitro stout.”

In a further criticism from Art-Language, as relevant then with regards to Latham’s group as it could be today with the Incidental exhibition, a critic observes,

Radical artists produce articles and exhibitions about photos, capitalism, corruption, war, pestilence, trench-foot and issues, possessed by that venal shade of empiricism which guards their proprietorial interests.

What is ultimately missing, as Eleey points out, is a fundamental sense of opposition from within the system. In most instances, the artists attempt to operate outside of the organizations they are targeting, whereas the APG sought to do so through the infrastructure that serves them, essentially operating from an inside-out approach. While the questions asked are worthy, some the methods fall short of the aims. Furthermore, for a show that aligns itself within an ethos of a movement that sought to dematerialize artwork and take it beyond the boundaries and sites of conventional institutions, it is odd to encounter such an exhibition within the confines of the standard white cube, or, for that matter, in New York. As Lucy Lippard, author of Dematerialization of Art stated in an interview with Ursula Meyer in 1973, “One of the important things about the new dematerialized art is that it provides a way of getting the power structure out of New York and spreading it around to wherever.” apexart’s coaptation of the APG’s practices of dematerialization and politicization, along with its move away from the authorial and symbolic roles of the artist makes for an exhibition that raises many fundamental questions concerning art and its role as tool of political and social activism. Many of the works within the Incidental Person embrace aspects of Latham’s original mission, but few seem to reconcile the flaws that led many to criticize the APG or the broader Conceptual art movement as a whole. The most ambitious of these works still leave unanswered those questions left by the APG’s legacy. What and where is the art? What is the social value transmitted by such works, if any? What are the risks with such work? Certainly raising such vital questions about the value and presentation of art remains important, and the apexart exhibition succeeds in doing justice to the provocative legacy of the APG. Whether that legacy is worth revisiting in the first place, however, is more open for debate.

]]>