Komar & Melamid, UNITED STATES: MOST WANTED PAINTING, 1994. via Prison Photography

Design and Crime (And Other Diatribes)

Hal Foster, Verso 2010

Going Public

Boris Groys, Sternberg 2010

On October 2, 2009, the New York Times Style section named the Facebook generation’s latest Warholian moment. In a breezy trend piece, author Alex Williams took a stroll through outer borough flea markets and Manhattan boutiques, returning to announce the ubiquity of ‘curating’–that formerly art-world practice of separating cultural wheat from chaff. With an excess of options threatening consumer decision-making, Williams reported that ‘curating’–nebulously defined as putting a financial premium on style–had been taken up by the service industry as a hip new sales tool. Liberated from museums, it’s been appropriated by high-end sneaker retailers, Brooklyn pickle salesmen, and anybody with aspirations of adding a dash of elitist appeal to their chosen–and usually charmingly eclectic–profession.

Curation-as-sales technique, of course, is just one example of the term’s incursion into culture writ large. (Though ironically, as of this writing, ‘curating’ has yet to make it past the cerberii of Microsoft spellcheck). As curating has crept into public discourse over the past several years, it has evolved from a practice into a buzzword for self-presentation, a nickname for saying, as the Times paraphrases it, “I have a discerning eye and great taste.” DJs curate music, thrift stores curate clothes, and increasingly, writers curate media. Selection, in this capacity, is now on par with creative production, and it’s valued accordingly. Like bouncers at elite nightclubs, tastemakers price items by context, declaring them less worthy when removed from proper, well-heeled company.

Seven years before the Times flagged the trend, Hal Foster noted its underpinnings in his 2002 essay “Design and Crime,” a work deemed resonant enough to merit a re-release from Verso this spring. The Princeton art historian documents the spread of design into previously uncharted territory, mapping its evolution from the study of objects into a comprehensive worldview. Design, he writes, now applies to both object and subject, enveloping how somebody’s apartment looks to the kind of prescription medication they’re taking:

Today you don’t have to be filthy rich to be projected not only as designer but designed–whether the product in question is your home or your business, your sagging face (designer surgery) or your lagging personality (designer drugs), your historical memory (designer museums) or your DNA future (designer children)… Just when you thought the consumerist loop could get no tighter in its narcissistic logic, it did: design abets a near-perfect circuit of production and consumption.

With “jeans to genes” falling under a common qualitative rubric, people advance from being image-producers to images themselves–embodied examples of taste, skill, and ethics. In short, we become the sum of our choices, and as such, are required, as Boris Groys puts it, to take “aesthetic responsibility” for ourselves. “Design today has become total,” Groys writes in “The Obligation to Self-Design,” and in lieu of an artistic avant-garde, we’re left with curators.

In the years since Foster first cast suspicious eyes on his surroundings, the internet–that formerly collective blank slate for invention and aesthetic–has become a field for individual representation, with personality filtered through the machinations of design. While the early years of the web were distinguished by nobody knowing who was a dog, the culture of web 2.0 is one of transparency, accountability, and auto-archiving. Thanks to social media, “the practice of self-documentation has today become a mass practice and even a mass obsession,” Groys writes in his new essay collection, “Going Public,” and as the process has been streamlined, it’s been corporatized. While the internet becomes more seamless, technological leaps have enabled the private sector to transform the web into an intangible Fosterian bazaar; a space where integrated paywalls, virtual shopping carts and omnipresent ads degrade the boundaries between consumerism and identity. Simultaneously, the public has been handed the means of production, enabling anybody–and everybody–to make art.

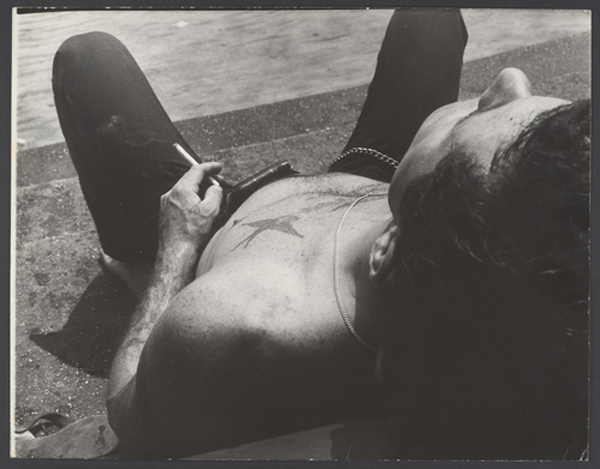

Komar and Melamid, Symbol of the Big Bang # 213, tattoo on David Ferris's shoulder, New York City, 2003. via Komar and Melamid

But Groys is less interested in the economics of culturemaking–“everything can be interpreted as an effect of market forces,” he sniffs in his introduction–than in its social dimension. A German-born critic and media theorist, Groys spent his younger years behind the iron curtain, where he embedded with the artistic underground and coined the term “Moscow Conceptualism” to describe artists’ subversive relationship to socialism. Decades later, he turns his attention to another aesthetic regime; ours. With technology eradicating the barriers between artists and masses, Groys approaches artmaking from the vantage point of the producer, calling for a new paradigm to reflect the decentralized working of cultural production. As what people post, link to, and thanks to the ever-expanding social media net, what they read, is deemed a growing reflection of who they are, “Going Public,” probes the differences between making art and producing one’s identity in the brave new information ecosystem.

The question at the heart of “Going Public” is deceptively simple: “How can a contemporary artist survive this popular success of contemporary art?” No clear answer is offered. Groys’ skill lies in framing scenarios rather than proposing solutions, and lacking a single thesis, he constellates his writing around the idea that the artist is going the way of Barthes’ author; which is to say, disappearing quickly. This claim is supported by a survey of the art scene: in place of paintings and sculptures, artists are increasingly drawn to participatory projects, public installations, and ephemeral works–pieces oriented toward process over physicality. Interesting, perhaps, but disconcerting for artists: as collaborative art gains ground, the context they work within is one of their own de-professionalization.

Groys’ most incisive observations about this scene are sociological, in a sense. In “Loneliness of the Project,” he offers an elegant assessment of the project as a professional/creative gestation period–a form of “socially sanctioned loneliness” that suspends people outside of the flow of the workweek with society’s collective blessing. This vision of installment-based time is the counterpoint–or perhaps the anecdote–to Michel Houellebecq’s vision of contemporary alienation, and apart from him and writers such as Andrew Ross, it’s one that’s rarely explored amid the global reformatting of professional life. But Groys isn’t a labor theorist, opting for what he terms a ‘poetic’ approach towards cultural economy. As more people drift outside the parameters of the 9-5, “project formulation is gradually advancing to become an art form in its own right,” he writes, and only in the face of monumental events–natural disasters, terrorist attacks, death in the family–are we knit back into the common fabric of world affairs.

Which brings Groys to the larger issue undergirding the ascent of design: If the personal is political, then the private is now as well, to put a Zuckerbergian update on a stock slogan. In “The Production of Sincerity” Groys examines how the aestheticization of private life has bled into the political sphere, shaping media culture in its own image. As excessive design induces suspicion–consider natural reactions to unnaturally airbrushed models or PR statements–Groys posits that the media has responded to this with an economy of sacrifice, demanding sincerity and disclosure in exchange for public trust. Celebrities admit to guilty pleasures, politicians hold press conferences to confess infidelities, and the public embraces them all the more for it, extending sympathy and network TV show as consolation prizes. “When art becomes political,” Groys writes, “it is forced to make the unpleasant discovery that politics has already become art.”

Forgetting, for a moment, the cynicism and celebrification that have flourished in our political climate, this may not be as insidious as it sounds: Because appearance is often more consistent than content in the political sphere–and tends to reveal more than it ostensibly lets on–Groys concludes that, “modern design belongs not so much in an economic context as in a political one.” And, yet, this is where things come full circle. Politics may be subject to the whims of design, but it’s also the realm in which hyper-individuation collapses, and the vanity of taste is subject to demands beyond its own making. So long as a carefully worded Tweet can buoy a Senator or set the Middle East ablaze, then politics is also where curation breaks down; or at least, becomes collaborative; the point where the public sphere confronts the private in a collective and potentially generative way. There was once a time when going online meant evading the challenges of the real world; now, in the era of self-design, they’ve become one in the same.

]]>

Lawrence Weiner, Time/Bank Currency, 2010. Photo: Julieta Aranda. Via Austin Thomas.

A universal search of e-flux’s Time/Bank project at 3:56 p.m. on Friday, November 12, turns up the following results, listed in descending chronological order:

For one hour of time, robgreene in Los Angeles “will provide 1 hour of DJing with either vinyl records, CDs, or both of all your favorite soulful, nostalgic jams!”

For 24 hours of time, Claudia in Germany asks readers to “send me your artwork, whether finished or in progress, and I will ask random passers-by and/or my grandma how they think you should proceed.”

And for two hours of time, mjg in New York offers to “draw you a picture and mail it to you (or exchange in person if you live in NYC). All I ask in turn is that you get a frame for it and hang it proudly on your wall.”

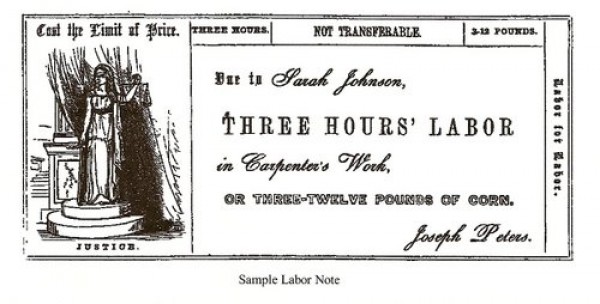

The currency is time, and the product is cultural work, or auxiliary services surrounding it. In exchange for translating a press release, babysitting a four-year-old or letting somebody crash on their couch—the definition of ‘work’ is subject to interpretation—participants in e-flux’s Time/Bank are awarded “Hour Notes” redeemable for goods on sale at the organization’s Essex Street storefront. (And not just there: a satellite location recently opened in Liverpool, and plans are afoot to launch more). To get involved, time bankers post ads detailing their skills or requesting somebody else’s, positioning themselves in a barter economy that’s occupationally delimited but functionally global.

e-flux dates the origins of time-banking back to British social reformer Robert Owen and American Josiah Warren, an anarchist who brought the system stateside in 1827 with the Cincinnati Time Store. Since then, time-banks have materialized in college towns and economically depressed communities across the country, realigning the relationship between functional value and work in an era of neoliberalism and abstract capital. The most high-profile American system currently operating is the Ithaca Hours, which Paul Glover established in 1991 and christened after its post-industrial hometown. London and Glasgow are also home to notable inner-city time banks, as is the student haven of Madison, Wisconsin, whose branch has over a thousand members. With its 21st century spin on utopian socialism and reliance on grassroots organization, it was only a matter of time before the system was adopted by artists.

Throwback, via Josiah Warren Project

While time banking itself falls within an older mold, e-flux’s iteration has a slightly different audience. By focusing exclusively on culture workers, Time/Bank highlights the precarity that unites the creative class with low-wage laborers in the brave new globalized economy. As Andrew Ross observes in Nice Work if You Can Get It, “flexploitataion” and the decline of Fordism have rendered white-collar workers structurally vulnerable, a position that’s mirrored in the migrant workforce. “Once they are in the game,” Ross writes of creative workers, “some of the players thrive, but most subsist, neither as employers nor traditional employees, in a limbo of uncertainty, juggling their options, massaging their contracts, managing their overcommitted time, and developing coping strategies for handling the uncertainty of never knowing where their next project, or source of income, is coming from.” Broke culture workers, in short, are the ideal participants in an economic system that feeds on precarity. Not a new conceit, but one that feels especially significant when surveying the cradle-to-art school wares at the Essex Street store. Time/Bank may enable creative workers to live comfortably as leftists, but it also implies that this is perhaps a less voluntary association than in the past.

A quick scan of the shelves offers dissertations’ worth of material for future cultural anthropologists. In addition to toothbrushes and a variety of dried foods, necessary goods include the following: texts on Hegel and anarcho-syndicalism (30 minutes); condoms (20 minutes); paintbrushes (15 minutes); yoga mat (one hour); guitar (14 hours); Casio watches (2 hours); hemp soap (one hour); Chia Lincoln (one hour); stovetop coffee maker (2 hours); and a blue Peugeot bike—originally fifteen hours, reduced to ten due to necessary repair work. These are the must-haves of a certain subset of the cultural stratosphere, revealing that the project’s real divide is social, not economic.

With this in mind, a prescient question that Time/Bank raises is what counts as work in the creative economy, and subsequently, what qualifies as luxury. An easy way of approaching this is through the division between material and immaterial labor: construction or dog walking read easily as physical work, but what about conceptualizing web projects or curating art shows? In the context of the project, it’s all the same, with quality and value determined by users and unmoored from physical output. Assuming the time costs are the same, fixing a guitar or building a shelf is worth exactly as much as German-English translation or theorizing about art. Ultimately, the question isn’t one of labor, but of value.

e-flux, PAWNSHOP, 2007. Via e-flux

In 2007, e-flux planted the seeds for Time/Bank with PAWNSHOP, a project that explored the “poetics of circulation and distribution” by inviting 60 artists to contribute works that would be reclaimed or eventually pawned to the public. “A pawnshop,” the press release explains, “is a stage where merchandise and money dance in a choreography that could have them circle back and cancel each other out, but in fact rarely does.” Rather than floating back and forth over the hazy border between exchange value and use value, items at pawn shops typically sit unused on shelves, slowly going to rot while their monetary avatars are off having a good time. By sticking 60 indisputably valuable artworks in a pawnshop, e-flux forced a clash between contradictory models of value, momentarily transforming a holding cell for unwanted or useless but valuable goods into a kind of gallery space. With the distance between goods and capital ever increasing—or at least, goods and our ability to value them—Time/Bank picks up where Pawnshop leaves off, creating a nearly closed system that’s pegged entirely to use value.

As anthropologist David Graeber points out in his incisive article about art and immaterial labor—a concept he thrashes before leaving for dead—the value of art comes from its recognition by moneyed tastemakers. Artists produce things, Graeber writes, physical items that “financiers can baptize, consecrate, through money and thus turn into art.” Bankers don’t produce tangible items, but it’s their verdict that determines whether an artist shopping in the Time/Bank store is doing so out of luxury or necessity. But Graeber insists that this isn’t cause for anti-capitalist despair: money migrating from bankers to artists enters alternative spaces much the way that government welfare checks do. “It is never clear,” he writes of art sales, “who exactly is scamming whom.” This opaque system of valuation is the referent in Time/Bank, and it’s one that e-flux cleverly undermines by positing a workable alternative. Without necessarily suggesting a fundamental realignment, the project’s central insight is that people will work for what they care about, so long as they’re allowed to determine what matters to them.

]]>

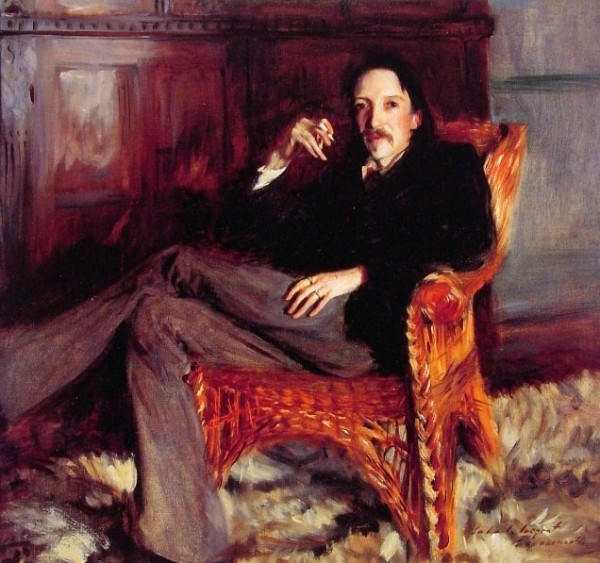

John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson, 1887. Via wikicommons

A new feature debuts today on Idiom, Idle Thoughts, wherein writers engage with older, canonized or forgotten works and ideas. Jessica Loudis, who will be leading the charge, such as it is, begins, appropriately enough, with Robert Louis Stevenson’s “An Apology for Idlers,” as she wanders her way through Penguin’s Great Ideas series. More to come, if we can get around to it.

Seven years before Treasure Island was first serialized in a children’s magazine, Robert Louis Stevenson wrote “An Apology for Idlers,” a short essay on the virtues of sloth. He was 25 at the time—the ideal age to take up the charge—and had recently swapped a prospective future in engineering for one of books, bohemia, and his soon-to-be signature velveteen jacket. Most likely, he was feeling defensive about the decision.

Idleness is generally associated with 19th century dandies—Stevenson’s mustache alone earns him the distinction—and the French, but when “Idlers” was published in 1876, it intersected a longer tradition of literary lethargy. Japanese monk Yoshida Kenkō philosophized about the subject in his 14th century book, Essays in Idleness; Paul Lafargue wrote The Right to be Lazy from his prison cell in 1883, (he was, ironically, Karl Marx’s son-in-law); and fifty-six years after Stevenson, Bertrand Russell attacked the “immense harm… caused by the belief that work is virtuous,” in his own essay “In Praise of Idleness.” More recently, Cabinet Magazine has taken up the cause’s mantle, and assuming they ever go to print, several academic books are forthcoming on the subject.

N.C. Wyeth, Robinson Crusoe (endpaper), 1920 via Worth Point

Stevenson writes about idleness as it deserves to be written about—languorously, and with a hint of condescension. He characterizes the busy as a breed of latter-day zombies: glassy- eyed and driven, bereft of the imaginative capacity for dabbling, and thus resigned to a life of unacknowledged boredom. “As if a man’s soul were not too small to begin with, they have dwarfed and narrowed theirs by a life of work and no play; until here they are at forty, with a listless attention, a mind vacant of all material of amusement, and not one thought to rub against another, while they wait for the train.” It’s easy to mock Stevenson’s dismissiveness, but he’s quick to delineate between idleness—a form of inquisitive and generative aimlessness—and laziness, its apathetic doppelganger. The distinction is particularly relevant to the book’s desired audience: aspiring artists, or “young gentlemen,” as Stevenson would have it, eager to while away their time. In this regard, “Idlers” is less of an apology than it is a dispatch from the field.

Idleness is a slippery subject, as writing about it betrays its intent. There’s an out-of-time quality to Stevenson’s prose, a nostalgia for lazier moments that isn’t dissimilar to daydreaming or what I’d imagine light doses of morphine to feel like. After some musing about age, this intellectual meandering is called into relief in the final few essays—fond recollections of artists’ colonies outside Paris and seaside walks in the Bay of Monterrey—that feel vaguely as if they were written from a convalescent home. (Tellingly, Stevenson suffered from chronic illness for much of his life). Unlike travel writers who pack their writing with high-octane immediacy, Stevenson does the opposite, glazing everything over with a sepia-toned nostalgia, a wistfulness for things never to be recovered. This adds a slightly narcotic tint to his essays, but also makes it especially surprising when action does occur, like when the young artist sets fire to a California pine to see whether it will burn.

Reading “An Apology for Idlers” is to witness the process of aging over 113 pages. Idleness begins as a youthful pursuit, a form of undirected engagement; and ends as a mode of nostalgia, a trap door allowing the author to escape into literary solipsism. For those who can afford it, idling is a luxury as well as a curse. But as grim times make idleness more an imposition than a choice, “Apology” is an elegant reminder that sloth doesn’t always deserve its bad rep: It’s nice time, if you can use it.

]]>

Petrit Halilaj, The places I'm looking for my dear are utopian places, they are boring and I don't know how to make them real, 2010. via Art Agenda

If viewers were to take the theme of this year’s Berlin Biennale—the defiantly cryptic “what is waiting out there” –at face value, it would be safe to assume that the answer is large-scale installations, room after room of line drawings, a handful of chickens, and slightly didactic political art. Instead, curator Kathrin Rhomberg offers an even more obtuse definition: the exhibition “present[s]artistic positions which direct their gazes outward, at reality, while also attacking the aloof pleasure taken in the outward gaze.”

The tension between political engagement and fixed critical positions may have been the stated theme of the show, but a lack of uniformity emerged as the more prominent one. With six sites sprawled across the city, the Biennale seemed content to prioritize scope over cohesion, impressing the viewer—and especially those from New York—with the sheer amount of space at its disposal. The exhibition’s flagship space was the Kunst Werke Institute for Contemporary Art, a renovated margarine factory in downtown Berlin, but alternate sites fanned out across Mitte and Kreuzberg, colonizing the city with a vague statement about what Berlin’s art scene has to say in 2010.

Visitors enter the KW site through the basement of the building, walking through a series of narrow passageways before emerging into a basketball court-sized room taken up by the wooden skeleton of an unfinished house. The house—as well as an accompanying courtyard occupied by about a dozen chickens—comprised Petrit Halilaj’s installation, The Places, I’m Looking for, My Dear, Are Utopian Places, They Are Boring and I Don’t Know How to Make Them Real. Pigeons milled around the upper sections of the rafters, and despite being grandiose in scale, the piece firmly established the show’s DIY attitude, creating the atmosphere of a teenager’s house party in his parents’ mansion. Two more floors of the four-story building were turned over to Halilaj’s work (also inexplicably chicken-themed) and the rest of the site showcased the exhibition’s recurring themes; immigration, sexuality, and anti-capitalism.

Hans Schabus Klub Europa, 2010 via Artnet

At the Oranienplatz 17 site in Kreuzberg—an abandoned department store—viewers were ushered past a graveyard of coat racks before entering the heart of the show, five floors taken up largely with video art. When visitors were ready to resurface, they were invited into the attic, a windowed space overlooking Oranienplatz square that some maudlin curator had chosen to fill with Jeff Beck. The musical selection was a tipoff—at its worst, the work at KW and Kreuzberg seemed reminiscent of an art school thesis show: heavy-handed and unwilling to depart from predictable themes. Short films featured artists antagonizing Israeli border guards and women making out in a hallway; video installations juxtaposed Wall Street traders with African tribal warriors; and in one installation piece, the artist lay in a Plexiglas box with names of diseases written on his body, a “performative exaggeration depict[ing] the industrialization of life itself,” the description informed inattentive visitors.

For my money, the Biennale’s most impressive—and subtle—works were sculptural, and among these, the interventions into the vast exhibition spaces were most satisfying. In Klub Europa German artist Hans Schabus placed a woolly mammoth and decapitated stegosaurus in the middle of the Oranienplatz’s narrow courtyard, making it difficult for viewers to catch the entirety of the visual joke without leaning out the window to see it. With Das Haus Bleibt Still (the house stays still) Adrian Lohmüller set up a Chinese-water-torture piping system that slowly dripped onto a salt block, creating crystal formations that melted into a nearby bed. On the non-sculptural end of things, other notable pieces included Vietnamese artist Dahn Vo’s dismantled computers, which were alternately placed behind display cases and laid out flea-market style; and Thomas Judin’s haunting photos from his series Echoes. In keeping with the show’s quieter theme of ‘home,’ Vo also opened up his apartment as one of the exhibition’s venues.

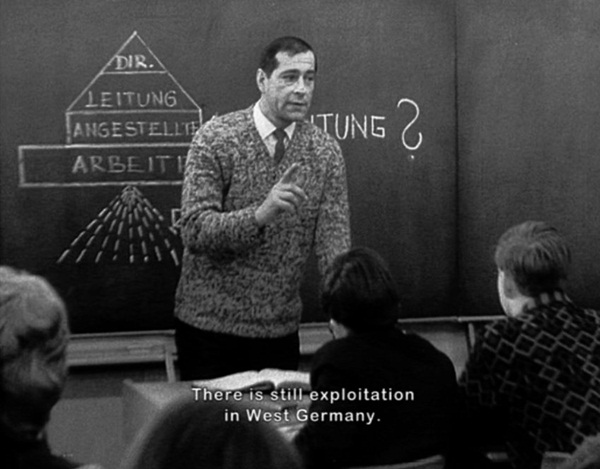

Phil Collins, Marxism Today, 2010 via Luis Hipolito

One piece that certainly deserved more attention than biennale formatting permits was Renzo Marten’s Episode III: Enjoy Poverty a 90-minute gonzo art documentary that debuted two years and is now making the gallery rounds. The film poses the question of whether poverty is a resource—Martens suggests that it is—and depicts the artist traveling through the Congo with a neon sign instructing villagers to “enjoy poverty” by assuming control of their images in the media. A la Fitzcarraldo, Martens travels largely by boat, and many of the film’s most striking moments feature that sign flashing in the darkness.

With pieces like Enjoy Poverty and Phil Collins’ excellent film Marxism Today scattered through the show, the Biennale’s shortcomings were not a failure of the art, so much, but sprung form an inability to wrangle the pieces into conversation with each other. Granted, this is a hazard of all big exhibitions, but by both overloading the space and refusing to organize it with coherent themes or questions, the curators handicapped both artists and viewers. The show was ultimately very worth seeing, but perhaps in the future, Biennale curators might consider adopting one of the critical vantage points they went out of their way to reject.

]]>

Sharon Hayes, Parole, 2010 via the Whitney

Last weekend, Sharon Hayes DJ’ed at the Guggenheim. Thinking of the hipster meet-and-greets that colonize city museums over the summer, I assumed the event would skew more towards the social than intellectual (and possibly include some sort of open bar) but failing better research, I was proven wrong. Instead, the event—which took place during the afternoon—featured Sharon Hayes spinning spoken-word records in the lobby of the museum as tourists pored over maps.

Hayes’ set was part of the Guggenheim’s Haunted show—an examination of how photography and video have responded to new forms of documentation over the past half century. Assuming viewers walk straight up the spiral, the show opens on Warhol and closes on Tacita Dean, with a scattered theoretical survey of post-‘60s art in the middle. Focusing on photography—the imperfect marriage of ghost and machine—the curators posit that in the 21st century media landscape, images negotiate the collective experience of history and memory, and for better or worse, can be remade at the artist or viewer’s volition.

Sarah Charlesworth, Herald Tribune: November 1977, 2008 via the Guggenheim

The blank power of the image is elegantly unwound in Sarah Charlesworth’s Herald Tribune: November 1977, a day-by-day breakdown of that month’s front pages with articles whitewashed away. Free of text, the photos invite original interpretations, turning a site of fixed meaning into a new kind of canvas, a space for referents without signifiers. By neutralizing language, Charlesworth displaces the artist, calling attention to art’s natural capacity for deception. In her Small Wars series, photographer An-My Lê takes this as her primary concern, documenting Vietnam War re-enactors in the style of ‘70s photojournalists. These ‘fake’ photos are indistinguishable from wartime ones, and they rely on captions to fill in the punchlines. A Vietnam refugee herself, Lê toys with the sanctity of war images to evoke a scene out of central casting.

In Sharon Hayes’ work, art is less a site of deception than it is one of subjective interpretation. Through audio, film and performance—her projects have been variously described as “re-speakings,” and “re-presentations”—Hayes investigates the reverberations of political speech over time, examining how the process of documentation gives way to perceptual shifts. In Parole, her piece at the 2010 Whitney Biennial, Hayes embedded audio of civil rights speeches—James Baldwin; lesbian activist Anna Rüling—over contemporary footage shot in the privacy of homes and public spaces. At the Guggenheim, Hayes’ references were strictly ’60s. Angela Davis, Malcolm X and Spiro Agnew made it into her repertoire, and less explicitly political LPs—the moon landing, Edward Murrow speeches—were stacked up behind her. This “unique sonic event,” as the museum would have it, turned out to be an excellent supplement to “Haunted”—a performance that enacted the show’s central questions while exposing its shortcomings.

An-My Lê, Small Wars: Lesson, 1999-2002; via SFMOMA

Political speech is always at risk of losing its potency when removed from its original context, but sticking it in a lobby during a weekend rush threatens to brush against satire. (Does anybody listen to pianists in malls?) In her previous projects, Hayes broadcast historically charged speeches in parks and homes—spaces where the private and political meet in personal and unanticipated ways. Under these conditions, Hayes suggests, language is able to accrete new meaning while acknowledging the loss of earlier contexts. Performing live at the Guggenheim, however, doesn’t lend itself to subjective experience. Aside from the technical problems associated with projecting sound in the space—a spiral, it turns out, isn’t the most acoustically generous shape—Hayes’ audio intervention lost some of its luster in the sanitized space of the museum.

But while the lobby of the Guggenheim isn’t a great place to start a revolution, it did provide Hayes with a platform for a different kind of critique. As Hayes played her records, visitors tuned in and out, listened ambiently, and occasionally committed their attention to the unlikely DJ. The audio may have been political, but the performance was about the social conditions of politics—a commentary on how we experience media. When read in this way, the intervention seemed to reflect Haunted’s faith in the infinite possibility of media, as well as its depressing underlying condition: it’s always possible to change the channel.

]]>

Leon Levinstein, Washington Square Park, 1967. via the Met

There’s always something dissonant about street photography in a museum. Polite observation and quiet reflection aren’t what these photos ask of their viewers, and when standing before a Robert Frank or Gary Winogrand, it’s difficult not to register a vague note of jealousy over the rift between well-behaved voyeurism and the glancing exuberance of the subjects. Or perhaps it’s just that on a nice summer day, I’d rather be outside. In any case, I’ll assume that the faulty air conditioning at the Met’s Hipsters, Hustlers, and Handball Players show was intended to address this concern, and to recreate the sweltering intimacy of photographer Leon Levinstein’s post-war New York.

Levinstein moved to New York in the late 1940s to study art and painting at the New School, and while he wasn’t partial to titles or dates, his photos from the ensuing decades carry many of the city’s signatures. During these years, Levinstein lurked on the streets and beaches of hardscrabble neighborhoods—the Lower East Side and Coney Island were favored targets—stealing shots before the show’s eponymous subjects could catch him. In the pre-paparazzi days of the 50s, conditions still worked in his favor. Photography was relatively rare, and many of his subjects, Levinstein noted in a 1988 interview, “didn’t know what the lens was.” This lack of affect suffuses every photo—his subjects sneer and pose in ways that should be impossible under the gaze of a camera. Seeing his world from the panoptic age of social networking, Levinstein’s work feels hyper-modern, and what’s more, utterly un-reproducible.

Leon Levinstein, Woman in Blonde Wig and Tight Dress, New York City, 1960s. via the Met

Levinstein’s photos recall the vibrancy of Robert Frank’s urban scenes and the unselfconsciousness of Walker Evans’ hidden-camera subway shots, but with elements of levity and the grotesque. He’s happy to trade unguarded expressions for the instant of surprise, to capture the shock of recognition when making eye contact with a stranger. As a result, Hipsters has the democratic feel of surfing the crowds during a New York summer. Levinstein’s portraits, often taken point-blank, are like catching a fleeting detail while crossing the street, or noticing a reflection in a store window. His affinity for high-contrast tones only heightens the drama. A notorious loner, Levinstein cast himself as a ghostly flaneur, piecing together fragments of a city that seems especially sly and solitary when seen through his eyes. In two works hanging side-by-side, a bloated male torso (head excluded) takes up the whole frame, while in the other, a pair of spindly, disembodied legs can be seen relaxing at the beach.

Given his theme and his predecessors, Levinstein’s photos are refreshingly unsentimental. Class and race are present, but they don’t suffocate under a heavy moral hand, and instead are intricately linked to a sense of place. Levinstein is stingy on details, but the photos are rife with visual clues. Neighborhoods are recognized at an almost visceral level—a young man on a dingy stoop evokes the Lower East Side of the 60s, while a shot of a well dressed woman—nose skyward, pill-box hat in place—provides all the detail needed to know that that the artist has hopped the train uptown. Levinstein revels in the dynamism of neighborhoods, and true to lived city life, his photos evoke the moment of seeing before meaning is registered. Tattooed arms are folded politely behind a squat frame. Couples kiss on the beach. A young hipster preens in a storefront window. This is New York, before there’s too much time to think about what it all means.

Leon Levinstein, Woman with White Purse, New York City, 1960s-1970s, via the Met

If street photography must fight to be more than a postcard to a single evolving second, then Levinstein, like Kerouac and Coltrane in their respective mediums, succeeds by summoning and shaping the force of his cultural moment. His New York is all movement and dirt, rife with the smell and noise of unpolished democracy at a time when technology was only beginning to reach the people. Levinstein recognized this and made it central to his work, approaching the city—and his role in it—with a wink, subtlety but deliberately caricaturing photography’s place in the changing era. It’s a show well worth seeing. I hope the air conditioning works when you do.

]]>

In 1985, a Princeton grad with a degree in art history took a job at Salomon Brothers, the white-shoe investment bank that presided over Wall Street during the bull market of the 1980s, and not for nothing, earned a mention in Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho. Only three years out of college and armed with a masters degree in economics, Michael Lewis spent several months in the Salomon training program before being shunted off to London to pass twelve hour workdays moving millions of dollars of other people’s money. “To this day,” Lewis marveled several years later, “the willingness of a Wall Street investment bank to pay me hundreds of thousands of dollars to dispense investment advice to grown-ups remains a mystery to me.”

Lewis only lasted for three years, but his timing couldn’t have been better: Salomon CEO John Gutfreund (pronounced ‘good friend’) had just taken the firm public, setting off the domino effect that would soon normalize six-figure salaries—and five-figure bonuses—and play a role in the 1987 market collapse crisis. Young traders were getting in when the getting was good, and as a self-appointed embedded anthropologist, Lewis was there to watch as a profession historically regarded as tame gave way to all-expense-paid Wall Street culture. When he published his debut book Liar’s Poker the following year, the gods smiled on Lewis’ timing once again: Salomon was in the midst of its precipitous downfall, and junk bonds—a topic featured heavily in the book—were implicated in the crash.

In a 2008 essay for Portfolio magazine that would later serve as the introduction for his book on the financial crisis, Lewis laid out the central concerns motivating Liar’s Poker—the unmooring of global capital from immediate stakes; the cult of easy money growing up around deregulation, and the seemingly arbitrary individuals (such as himself) assigned as its caretakers. Picking up from earlier:

I was 24 years old with no experience of or particular interest in guessing which stocks and bonds would rise and which would fall. The essential function of Wall Street is to allocate capital to decide who should get it and who should not. Believe me when I tell you that I hadn’t the first clue.

Within months of being published, Liar’s Poker became required reading for anybody with either a passing interest in finance or the alpha male ecosystem of ‘80s bond trading. Two decades later, it’s often grouped with other rise-and-fall accounts of the period—The Bonfire of the Vanities and Barbarians at the Gate rank among its contemporaries—but as one critic observes, Liar’s Poker has long been considered “the gold standard for the genre.”

The book’s title comes from a betting game traders played on the floor, and in the opening anecdote, Gutfreund challenges a top bond trader to a $1 million bet, only to be outdone when the trader suggests raising the stakes to “ten million dollars. No tears.” This pretty much sets the mood of Lewis’ Wall Street—a high-stakes casino where the money is always somebody else’s, and fitting in means emulating a frat boy. While several critics have noted that Wall Street pay usually comes in the form of restricted stock—a policy that forces traders to have a stake in the game—it’s still tough to challenge Lewis’ free-wheeling account of ‘80s excess. In a memorable example of trading floor shenanigans, bankers steal clothes from a colleague’s suitcase before he departs on a business trip; and in another, Lewis recounts the head of the mortgage department pouring a bottle of Bailey’s Irish Cream into an employee’s jacket pockets and instructing him to “buy a new one” when the trader complains.

As a financial wonk and Berkeley liberal, Lewis’ books have the rare quality of appealing to two audiences at once: bankers and people who consider reading financial journalism on par with a trip to the dentist. (I fall into the latter camp). In Liar’s Poker, passages about mortgage-backed bonds and credit default swaps—boiled down to their most digestible essentials—are interspersed with accounts of the self-described “Big Swinging Dicks” that ran the show, casting doubt on any theories that statistical failures were entirely to blame for looming financial troubles.

Lewis once claimed that his unofficial goal for writing Liar’s was to convince “some bright kid at Ohio State University who really wanted to be an oceanographer [to]… spurn the offer from Goldman Sachs, and set out to sea.” This backfired dramatically. “Six months after Liar’s Poker was published,” Lewis writes, “I was knee-deep in letters from students at Ohio State University who wanted to know if I had any other secrets to share about Wall Street. They’d read my book as a how-to manual.”

If the cautionary aspects of the book were lost on readers, Lewis’ follow-up, The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine, takes pains to avoiding repeating the same mistake, and this time, he’s got a painful recent history to help him make his case. In The Big Short, Lewis returns to Wall Street twenty-one years later to pick through the ruins of the post-crash markets and figure out who, if anybody, foresaw the apocalypse and came out triumphant. This isn’t the story of the crisis per se, but an account of how financial norms set the stage for disaster, and how several savvy Nostradamuses capitalized on the fall.

The anti-heroes of The Big Short are Steve Eisman, an abrasive subprime analyst; Mike Burry, an autistic one-eyed value investor; and Charlie Ledley and Jamie Mai, a pair of absent-minded money managers who take up residency in a Berkeley garage and never quite manage to shake their outsider status. For a variety of reasons, all these men recognize early on that the subprime mortgage market is built on sand, and despite sharing the insight with anybody that would listen—including Eisman’s dentist—they are largely ignored until the housing bubble pops. This is primarily a story of personalities, and though none of Lewis’ protagonists could be described as sympathetic, viewed against the amorphous forces of Wall Street, they come across as almost endearing, or at least only mildly distasteful.

While the rest of the financial world was busy gorging itself on the booming subprime market, the central insight of Lewis’ protagonists was unnervingly basic: a bond market that had grown to half a trillion dollars in 2005 (a figure that made the stock market look like “a zit” in comparison) was fundamentally worthless. Banks had developed sophisticated systems for extending credit to people who would never be able to pay it back, and thanks to increasing complex instruments for repackaging debt, few bankers selling bonds had any idea what they actually contained. For the benefit of non-wonky readers, Lewis explains the basic logic at work in subprime mortgages:

A giant number of individual loans got piled up into a tower. The top floors got their money back and so got the highest ratings from Moody’s and S&P and the lowest interest rate. The low floors got their money back last, suffered the first losses, and got the lowest ratings from Moody’s and S&P. Because they were taking on more risk, the investors in the bottom floor [the mezzanine] received a higher rater of interest than the investors in the top floor.

Theoretically, credit rating agencies were responsible for evaluating and policing these floors, but thanks to a loophole that allowed banks to shop around for ratings—not to mention a revolving door between Wall Street and rating agencies—the name of the game became hiding risk. Math and physics PhD were deployed to create opaque financial instruments that lumped together thousands of bonds—a process unironically called securitization—and the end products, collateralized debt obligations, ended up soliciting high ratings for risky loans and keeping naked emperors bragging about their respective wardrobes. While the internal dynamics were often poorly understood among their peddlers, the products were a runaway success, and ultimately, a main culprit in the crisis. When the SEC filed suit against Goldman Sachs last April for withholding information from investors, a key piece of evidence was an obscure CDO whose creator described his duplicitous product as the work of “intellectual masturbation.”

With varying degrees of insight about the landmines embedded in the financial system, Lewis’ protagonists set out to short the subprime mortgage market, essentially betting that one of the most profitable sectors of the economy was headed for implosion. And of course, they were right. By late 2007, only several months after the industry held a self-congratulatory conference in Vegas, the market started to melt. Banks were forced—for the first time—to accurately price subprime mortgages and come to terms with a numbers that were unthinkable only several months before. Suddenly, one of the largest crashes in financial history was on the brink of becoming reality, and only a handful of investors were left to say I told you so.

It’s worth mentioning that the people at the heart of the affair—buyers taking advantage of easy loans—are virtually absent from the narrative. Apart from the occasional reference to a Mexican strawberry picker with a $14,000 income and a $724,000 home (or the Vegas stripper with five mortgages) the crisis is mediated through hedge funders and analysts; financial insiders who happened to find themselves on the opposing side of mainstream opinion. Lewis isn’t particularly interested in getting the other side of the story, but in light of how much time he spends explaining how bankers justified risky practices to themselves, it would be helpful to know what things looked like on the other side of the financial divide.

With regard to the question of blame, in some respects, Lewis’ books resemble the films of documentarian Alex Gibney, a director best known for Academy Award-winning Taxi to the Dark Side, and Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room. Gibney eschews the ‘bad apple’ theory of systemic collapse, and instead hones in on how insulated cultures—financial, political, military—become perverted, continually rationalizing and disguising their own inconsistencies until the burden becomes too great to bear. While Lewis does pick his villains—John Gutfreund returns to feast on deviled eggs in the final scene of The Big Short—he also reads the subprime crash as symptomatic of deeper, culturally sanctioned flaws. Neither Gibney nor Lewis ever suggest that they see disaster coming—although sometimes the clarity of their narratives lead readers to this conclusion—but they do provide compelling accounts of how things go wrong, and more significantly, the ways in which people learn how to miss what’s right in front of them.

Since its publication, The Big Short, as with Liar’s Poker before it, has become something of a handbook for its financial age. A recent Politico article notes that the book “has been mentioned at least 15 times on the Senate floor,” and there’s been speculation that several of the SEC’s recent lawsuits have taken their cues from Lewis’ narrative. As a longtime critic of banking culture, and more recently, a politically influential one, Lewis has become a powerful voice for reform—a process that’s largely swayed between pro-business interests and populist anti-bankerism. By drawing unlikely readers into one of the most important—and abstruse—national conversations of the day, Lewis is doing his part to carve out a third path between these camps. With the long process of financial reform only beginning to get off the ground, his timing, once again, couldn’t have been better.

]]>

Today, dir. by Naftali Beane Rutter, courtesy of Waterbound Pictures

The trailer for Today, Naftali Beane Rutter’s documentary about a day in the lives of three New Orleans families, is unambiguous about its intent: “everything you’ve seen so far is about their hurricanes,” the opening text reads. “This movie is about their lives.”

Strictly speaking, that’s not quite true. While the word “Katrina” is rarely, if ever, mentioned in Today, the storm’s fallout is so deeply embedded in the lives of the protagonists that it hardly merits reference. Allusions to Katrina are oblique—people offhandedly mention “flooding” or “the storm”—and in one instance, a pediatrician cheerily asks where a family ended up after they were evacuated. But the hurricane’s presence is there, and its aftermath has been casually entwined with troubles that predated the storm. Of the three families profiled, one lives in a FEMA trailer, and the other two, respectively, survive off money earned from repairing flood damage and keeping the crime rate down in one of country’s most dangerous cities.

Today, dir. Naftali Beane Rutter, courtesy of Waterbound Pictures

The film is shot over the course of a day and alternates between families, documenting the first alarm to the moment everyone heads to bed. Aside from a city, the Blaises, McPeeks, and Stanichs initially appear to have little in common: the Blaises live in a rural area near the bayou and fish for their dinner while the McPeeks and Staniches are lucky enough to have homes with foundations and regular paychecks. But domestic life soon emerges as the film’s unifying thread: everybody has routines to attend to, and many of the film’s best scenes involve adults interacting with the small and unfailingly adorable kids they watch during the day. Because Rutter avoids the New Orleans of tourist brochures, his vision of the city is grounded on the minutiae of family, in all its varying iterations. This succeeds in conveying the depth of domesticity, but at the same time, it doesn’t address the elephant in the room: why families chose to stay—or come back—after the storm.

There’s not much drama in Today, but the film’s vérité style is executed so well that it hardly seems to matter. Dialogue is spare but meaningful, and Rutter has a knack for the understated humor of everyday life. Depending on the landscape, camerawork alternates between tight, off-kilter shots and extended gazes into Louisiana’s green distances. With many of the scenes set in the claustrophobia of cars and FEMA trailers, the camera initially seems all too aware of the limitations of its environment, but as with adjusting to darkness, gradually learns to see in tight spaces.

Today is Rutter’s first feature-length film, and he’s clearly got a promising future ahead as a documentarian. His work is engaging without being pedantic, and at its best moments, can be very funny. Despite peripheral issues, the central observation of Today is spot-on: in the wake of the storm, New Orleans is often viewed as more of a fetish object than a city. By focusing on real people, Rutter elegantly avoids this danger, and reminds his viewers why it’s Crescent City lives, and not hurricanes, that should be the real subject of attention.

]]>

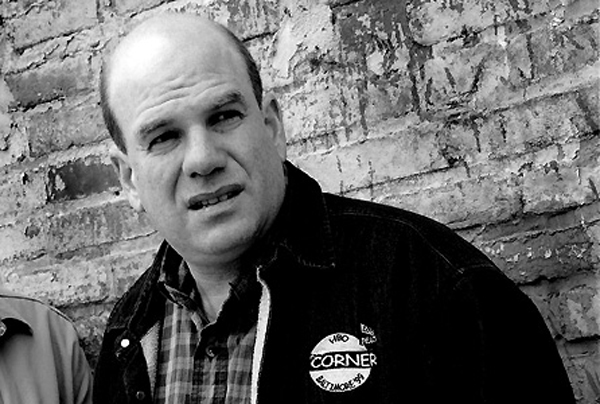

David Simon via bbc.uk

Treme is just as good as everybody hoped.

After releasing a breakthrough first novel, it’s not uncommon for writers to have a particular reaction to the challenge of producing a follow-up: they choke. Zadie Smith and Mark Haddon both fell victim to Second Novel Syndrome, and in one of the more dramatic casualties, after decades of work and hundreds of aborted pages; Ralph Ellison never quite managed to eke out his long-awaited second manuscript. With four TV shows and twelve years at the Baltimore Sun’s City Desk under his belt, David Simon is by no means an amateur writer, but still, the prospect of unveiling a new project after masterminding what’s widely considered the best show ever aired on TV has got to come with at least a little bit of pressure.

To compound the matter, when Simon first announced that he was working on a show about post-Katrina New Orleans, excitement about the news was rivaled by an equal degree of skepticism. After all, Simon knew Baltimore—he went to college in Maryland, worked the crime beat at the Sun, and spent years making the city his home. New Orleans, however, was a different story, and it wasn’t his.

But if the first episode of Treme is any indication, Simon fans and defensive New Orleanians can relax. For all the hype building up to Treme’s release—a New York Times Magazine cover, a Fresh Air interview, multiple Twitter countdowns—the show reflects the best of Simon’s ability, and avoids the pitfall of transplanting inner city Baltimore eleven hundred miles further south. Unlike The Wire, which Simon famously described as “a Greek tragedy in which the postmodern institutions are the Olympian forces,” Treme strikes a distinctly more human tone. Broadly speaking, the show is about musicians rebuilding their lives in a battered city, and Simon isn’t out to impose any kind of overarching agenda. If The Wire is at least partly about the culture of crime that grew up out of institutional failure, then Treme is simply about the culture of perseverance (and the perseverance of culture) that rise up when everything else goes to hell.

Appropriately, the most striking aspect of the show is its music. The beginning of the first episode opens with a familiar face—Wendell Pierce, formerly Detective Bunk Moreland, now trombonist Antoine Batiste—running late for a jazz parade and unable to cover the taxi fare. (In a jab to musicians, Batiste’s chronic brokeness is a running gag throughout the show). The parade’s music lures Davis McAlary (a wiseass local DJ played by Steve Zahn) out into the streets, and a later, especially entertaining scene pits McAlary’s NOLA hip-hop against his neighbors’ more classical taste. To his credit, while Simon’s soundtrack gives the city a voice—and counters the idea that jazz is the city’s only native musical son—what’s equally arresting is the show’s use of silence. It took New Orleans three years to recover two-thirds of its pre-Katrina population, and Treme is shot only three months after the storm. For as much attention as Simon pays to survivors, the city’s ghosts are never far off.

As he likes to do, Simon tackles the big themes of the Big Easy though a carefully chosen ensemble cast. There’s a musician, a DJ, a chef and a civil-rights attorney, not to mention an irascible John Goodman unable to stop dropping f-bombs while granting interviews about Katrina. (He’s an English professor). Clarke Peters, last seen as Lester Freamon, returns as Albert Lambreaux, a repatriated Mardi Gras chief who produces the show’s most visually memorable moment while dancing down the street in his best parade gear. Many of the show’s characters take their inspiration from real life (Goodman and Zahn are based off of a local blogger and jazz DJ, respectively) and in honor of the premiere, the Times-Picayune is running a series on the New Orleanians behind Treme characters. We’re only one episode in, but the show is clearly running on Simon’s narrative metabolism—there aren’t any cliffhangers to lure viewers back the following week, and Treme betrays few of the tics that viewers have come to expect from TV writing. This takes a while to get used to, but it seems well suited to the city at hand. Additionally, it lets Simon play to his strength: taking his time to develop complexity. It’s been said that this kind of narrative leisure is a luxury only afforded at HBO, but in terms of how well it works, it’s not HBO, it’s David Simon.

In what threatens to become an unfortunate sound byte, Simon described New Orleans to the Times as a city that produces moments. “Detroit used to make cars,” Simon told Wyatt Mason. “Baltimore used to make steel and ships. New Orleans still makes something. It makes moments.” This is undoubtedly cheesy (which Simon acknowledges) but when taken seriously, it’s also how Treme avoids feeling like cultural tourism. Treme’s moments stand out, and they do so with striking vividness. It’s too early, and generally pointless, to speculate whether Treme will be better than The Wire, but for the time being, it’s off to a great start.

]]>

Etgar Keret via nurithaviv.free.fr

Etgar Keret and Shira Geffen’s short film What About Me? opens on an Israeli border guard lazing about a checkpoint in the middle of the desert. When a salesman and his donkey approach, the guard informs the man that his papers aren’t in order—it’s a purple day—and that he’ll have to come back the next morning. “What about me?” the donkey asks. His papers are purple, and he’s allowed through. “Don’t worry, Nasser, by ten tomorrow I’ll be back,” the donkey remarks as he crosses the border. The man disappears, and as camera pans out, and the audience sees that the checkpoint is just that—a gate without walls, and a young soldier monitoring the vast expanses of nothingness on either side.

As a nod to Kafka’s parable Before the Law, the four-minute film—like much of Keret’s work— bears more than a little resemblance to its literary predecessor, give or take a talking donkey and chatty dog. Like Kafka, Keret is less interested in characters than in situations, and his protagonists usually find themselves accepting surreal and unexplained events (crazy-glued apartments, dead babies) with a sense of casual resignation. In Hat Trick, a story from Keret’s 2008 collection Girl on the Fridge, a bumbling magician is delighted and horrified when gruesome new items begin materializing in his hat, and in Knockoff Venus, an office worker develops a crush on the Roman goddess Venus, who’s taken a day job as a low-level copyist. The emotions undergirding Keret’s stories are familiar ones—loneliness, love, fear—but rather than addressing them outright, Keret literalizes them elsewhere, creating worlds in which the unspoken punctures reality with a bizarre and disturbing force.

Keret is widely known in Israel as one of the country’s leading writers, and six years after first being translated into English, he’s been gaining momentum on this side of the Atlantic as well. In addition to Girl, Keret’s published five other books (including two comics) and produced a handful of scripts for TV and film, several of which—including What About Me— were co-written with his wife, Shira Geffen. In lit-fanboy circles, Keret is best known as a leading practitioner of flash fiction—quick, tightly-managed stories often executed like jokes—and in cinephile crowds, he’s recognized for his abstract and darkly funny meditations on serendipity and death. Unlike other Israeli writers of his generation, Keret’s writing tends to avoid religion or politics, allowing him sidestep the country’s historical hang-ups while investigating the kinds of weird subjective experiences that tend to push people towards God or government in the first place.

Last week, BAM paid homage to Keret’s eclectic body of work with its own kind of flash retrospective, opening with his 2007 film Jellyfish (winner of the 2007 Camera d’Or at Cannes) and closing two days later with Wristcutters a film set in a post-suicidal purgatory mysteriously populated by the likes of Will Arnett and Tom Waits. As an author whose writing relies heavily on images, Keret’s stories are well suited for translation onto the big screen, and the series didn’t disappoint. In Jellyfish, visions of children emerging from the ocean and newlyweds trapped in claustrophobic hotel rooms are paired with quieter, more haunting details—a shirt twitches almost imperceptibly in a photograph, and a new bride’s lingerie reappears in storefront window. While these touches often go unnoticed on the page, they leave a subtle impression on the viewer, overlaying films that are already cryptic with an uncanny sense of visual déjà vu.

Keret is more of an atmospheric filmmaker than a narrative one, and his films downplay linearity in favor of carefully orchestrated ambiance. In $9.99, a film that sometimes feels like the claymation version of Happiness, characters drift around a Sydney apartment building like ghosts, silently craving a greater sense of purpose. More often than not, their searches take them in the wrong direction: a boy falls in his love with his piggy bank, a man removes his spine to please his girlfriend, and another character resorts to the discount self-help books referenced in the film’s title. Like much of Keret’s work, $9.99 tows the line between creepy and comic, but ultimately ends on a note of understated optimism, leaving viewers baffled but free of the post-Solondz urge to spend the evening in a closet with a bottle of whiskey.

To call Keret a postmodern writer isn’t wrong, but it’s not fully accurate, either. As he’s said in interviews, Keret is the product of Israel’s schizophrenic culture and a family that’s already the stuff of fiction (his brother is a militant anarchist and his sister an ultra-Orthodox Jew). A sensitivity to nuance, in short, is embedded in his personal DNA, and one gets the impression that it didn’t take a literary movement to get him there. “Our subjective experience is not a realistic one,” Keret told Ira Glass at BAM last week, and if his writing is based on any kind of realism, it’s true stories that are nearly unbelievable, the kinds of rare and singular moments that elude the one-to-one relationship of reality and language. In chasing these moments, Keret creates his own symbolic vocabulary, letting the reader (or viewer) know what he’s getting at without the baggage of context or explanation. After all, sometimes it just takes is a talking donkey to convey how arbitrary things really are. Before he came to BAM, I caught up with Keret to talk about fiction, cinema, and one very unusual laptop bag.

—————————————————————

Jessica Loudis: First things first. How did you get into writing?

Etgar Keret: I started writing when I was nineteen. It was during the three years of my compulsory army service. I had forty-eight hours shifts in a computer unit and during one of those shifts I wrote my first story, called Pipes.

JL: What was the story about?

EK: It was about a guy who builds those curled up pipes and rolls marbles through them. One day he builds a pipe that when he rolls marbles in they don’t come out the other end. He believes the marbles are disappearing and decides to build a big pipe in the same shape and crawl into it until he disappears.

I guess I really wanted to disappear those days.

JL: Your short stories tend to begin with these surreal, yet weirdly logical premises. How do you usually come up with the ideas behind them?

EK: I don’t do it on purpose; it’s just the way I think. When I begin a story it usually comes from a character, a situation, a visual image or even a sentence—it is never from what I’d define as a premise.

JL: So what would be an example of something just popping into your head and you turning it into a story?

EK: I was once in a bar and a drunk guy waved an empty bottle and threatened to break the bottle on my head. It was really noisy there and I misheard him saying that he was going to put me inside that bottle. A friend of mine with better hearing and stronger survival instincts said we should run out of there. While we were running this image of me being shrunk and kept inside a bottle stayed in my mind and I found myself writing a story. It wasn’t about the trapped in the bottle bit, more about loneliness and unfulfilled love (guess that was what I’ve experienced during that time) but that image of a guy inside a bottle appeared in it.

JL: What made you decide to start making films?

EK: Loneliness. Writing fiction is a pretty lonely business and I wanted to meet people and collaborate with them.

JL: Is for writing for film different from the way you usually work? Have there been any unexpected challenges?

EK: Writing short fiction is a completely internal process—there’s no interaction with the world around you. Working on film is completely the opposite, for good and for bad. What you learn as a filmmaker is that the friction with reality can lead your film away from the original plan, but that isn’t always a bad thing.

JL: Are there any specific authors or filmmakers who have influenced your writing?

EK: Many. The biggest influence was Kafka. It was really comforting to discover someone who is even more scared of life than I am.

JL: What are you currently reading/watching/listening to?

EK: I just discovered “The Wire” a few months ago. I’ve just finished watching the fourth season. This series is a master class in storytelling.

JL: You seem to have traveled a lot over the past few years to promote your books and films—what’s the strangest thing that’s happened to you while you’ve been on a book tour?

EK: When I landed in Perth I took somebody else’s laptop bag by mistake. He found me and after giving me my laptop back showed me he had $40,000 in cash in the bag.

JL: Wow. Did he say what the money was for?

EK: He was very polite but said that he would rather not tell why he was carrying all that money in the bag.

JL: What Are you working on at the moment?

EK: I’ve just finished the editing process of a collection of short stories that will be published in Israel in a month’s time.

]]>