Rehearsal for We're Gonna Die. Photo: Kristianna Smith

Idiom spoke with playwright Young Jean Lee (The Shipment, Church) about her upcoming show We’re Gonna Die.

Idiom: So, what is We’re Gonna Die?

Young Jean Lee: We’re Gonna Die is a show I’m doing with the company 13P. This is a company of thirteen playwrights who each get to produce whatever play of theirs they want, serving as the artistic director for that production, and when all thirteen plays have been produced the company implodes. It’s an opportunity for playwrights to do something much riskier than they would ordinarily get to do. In my case, I have my own theater company so presumably I could be as risky as I wanted with every show I do. But actually that’s not the case. I can be a lot riskier than playwrights who aren’t self-producing, but I can’t be so risky that the company loses all of its funding and collapses. 13P doesn’t have to worry so much about that since collapsing is the plan, so they encouraged me to do something really super crazy. And when I thought about the craziest thing I could do, I imagined myself performing onstage, since I’m not a performer and am a very physically awkward person. And then I thought, “What would be the most extreme form of performance I could inflict on myself?” And the answer came: “A one-person cabaret show with singing and dancing.” So I booked eleven nights at Joe’s Pub and started putting together a rock band. The concept behind the show is that it’s something that any ordinary person should be able to perform, and I’m using myself as a guinea pig. All the songs and stories are about heartbreak, loneliness, aging, sickness, and death. We worried that the show would be too depressing, but last night we did a test run in front of an invited audience and everyone totally loved it and was laughing and gasping through the whole thing. My hope is that other people will start performing it, although traditionally the whole point of a cabaret show is that it can only be performed by one particular performer.

Idiom: So the songs are your songs? Did you generate all the material yourself?

YJL: Yes I wrote the lyrics and melodies, but my boyfriend Tim Simmonds (who plays guitar in Future Wife) helped me refine them, since I’m not a musician and they were all pretty crude to begin with. I would basically just sing a bunch of stuff into a recorder and he would turn it into a proper song. I’m good at chorus melodies but not so good with verse melodies, and I’m not a singer so I don’t know how to sing things interestingly and had to imitate Tim’s phrasing since he’s a real singer.

All the other musicians in the band (which also includes Michael Demsyn-Hanf, Nick Jenkins, and Ben Kupstas) are terrific singer/songwriters themselves and front their own bands, so it was kind of a dream to work with them. The band’s sound wouldn’t be what it was without them. Ben Kupstas brought in a bunch of cool instruments that made a big difference. I had heard so much about all the annoying things band members do to each other in rehearsal out of ego, but there was none of that. Everyone was constantly volunteering to not play on songs if they thought it would sound better without them. Being songwriters, everyone understood that the overall sound of the song was more important than their part in it. I remember once we all wanted to cut a chorus repetition, and Mike was the only one who wasn’t immediately enthusiastic, and we asked him why and he laughed and said, “Because I kind of liked the glockenspiel part I was playing during that section, but obviously that’s no reason to keep it” and that was it.

Idiom: Can you talk a little about how you see this piece dovetailing with, or departing from, you previous work?

YJL: It definitely deals with themes I’ve always been obsessed with, but it does so much more directly. And it’s all about storytelling. I’ve found that my lyrics are way more straightforward than my playwriting. I am incapable of being weird or poetic or avant-garde in any way when I’m writing songs – if I try, it feels incredibly wrong and fake. So far, it looks as if this show will be much more entertaining and accessible than my other shows, but at the same time more disturbing and unpredictable. It is similar to my other work in that I’m trying to do something specific to an audience to unsettle them and plant questions in their minds, but dissimilar in that it uses entertainment rather than weirdness to disorient them. Also I’m performing it myself, which has never happened before and will probably never happen again.

Photo: Kristianna Smith

Idiom: Do you miss working with actors at all?

YJL: I really miss directing. When we’re in band practice and I’m singing, I can’t resist the temptation to make Tim or my associate director Morgan sing my part for me so I can stand outside and watch. The band members are all so charismatic that all I want to do is stand outside and make them do crazy things the way I’m used to. I feel sorry for the director, Paul Lazar, for having to work with me, but he’s been unbelievably patient and generous.

Idiom: Will there be an afterlife to this project? Are you recording an album?

YJL: I hope so. I would love to record an album. Tim and I have been recording demos in his bedroom using garage band (the first one we did was “I’m Spending Christmas Alone” which we released before the holidays). We recently released our second demo, “We’re Gonna Die”. They’re very thrown-together with Tim playing most of the instruments and definitely sound like demos, so we’d love to get into a studio with the whole band and record proper tracks. The songs are catchy and people are always asking us for them, so at Joe’s Pub we’re going to do live recordings and make them available via weblink to people who want them. I think no matter what happens, Tim and I will keep doing music stuff together, just because it’s fun.

Idiom: Can you speak a little about the challenge of creating a theatrical arc within a concert setting?

YJL: This piece has more of a theatrical arc than any piece I’ve ever worked on. I take the audience on an emotional journey through pain and comfort that leads to a big catharsis.

Idiom: Is there anything in particular you want the audience to take away from this piece?

Photo: Kristianna Smith

YJL: Well, the themes are so dark, but the show itself is entertaining and funny, so I would hope that the themes stick with audience members, but in a comforting rather than traumatizing way. We’re working hard to strike the right balance. One of our assistants couldn’t sleep after listening to one of our songs because it freaked her out so much, so we are trying to avoid that. Pretty much everyone who has heard the songs has said that the lyrics have stuck with them, but we want this to be a positive thing. Also, I’d want people to leave with the sense that they themselves could be interesting onstage in their own way, based on seeing non-actors sing and dance and tell stories with sincerity and commitment. In a way the whole show is really about humility, both in form and content. Last night after our invited run-through, one person said, “I felt like it could have been me up there telling those stories” and another person said, “I felt comforted when it was over.” That’s what we want.

]]>

via wysinfo

Messing about on the internets, I stumbled upon a publication called Jacobin. Impressed, I emailed editor and founder Bhaskar Sunkara about an interview. Sunkara claims to be an undergraduate at George Washington, but I think that’s a front for some kind of advanced sociological research project. We discussed publishing, muscle cars and the gourmet character of the new international. -SS

Idiom: I came across Jacobin when checking up on Walter Benn. Bless the Wikipedia. Care to do an email interview about small magazines, politics, and other mistakes?

Bhaskar Sunkara: Sure, my schedule isn’t full enough to pass up on any measure of free publicity.

Idiom: Ha! Now there’s an undergraduate response to an interview request. So for those unfamiliar with your mission statement, which I enjoyed very much, what was the impetus behind Jacobin?

BS: If by undergraduate you mean casual and endearing, then yes, yes it is.

Jacobin was founded as an outlet for critical engagement, explicitly on the premise that there is still an audience for these kinds of interventions. We took a survey of the publications on the left and found, with few exceptions, that they were either needlessly esoteric or that they had abandoned critical thought completely, preferring to offer up reassuring bulletins and rosy reports from the front. To echo our first editorial statement a bit, we want to avoid both traps. Substantive engagement does not preclude entertainment. Discarding stale phrases and ideas does not necessitate avoiding thinking itself. Voicing discontent with the trappings of late capitalism does not mean we can’t grapple with culture at both aesthetic and political levels. Sober analysis of the present and criticisms of the left does not mean accommodation to the status quo.

Also, Jacobin is largely the product of a younger generation not quite as tied to the Cold War paradigms that sustained the old leftist intellectual milieus like Dissent or New Politics, but still eager to confront, rather than table, the questions that arose from the experience of the left in the 20th century.

Idiom: Are there publications, past or present, that you see as walking a similar line, between commitment and criticality, as we say in the artworld?

BS: I think there is a lot to admire in the general trajectory of the New Left Review, though I may disagree with some of their political stances. I could say the same about “Third Camp” publications like New Politics. It’s not a coincidence that democratic socialists and “Trotskyist” circles survived the fall of the Berlin Wall. They’re still marginal forces, of course, but you didn’t see the same mass defection or “God That Failed” onanism coming from these traditions, precisely because their commitment to a better world wasn’t bound up with illusions about the Soviet Union.

Idiom: How would you characterize Jacobin’s orientation? And if there isn’t one, would you care to speculate at all about the significance of that refusal?

BS: We have a grandiloquent little introductory statement that states that our contributors are only loosely bound by common values and sentiments:

+ As proponents of modernity and the unfilled project of the Enlightenment.

+ As asserters of the libertarian quality of the socialist ideal.

+ As internationalists and epicureans.

Not all of our contributors are self-described “Marxists,” but they all have a structural understanding of capitalism that goes beyond the both the illusions of the social democratic critique and the spastic moralism of the anarchist one. In practice the means some impassioned discontent with the state of the world today, but also a serious (and tempered) perspective on what’s required to change it. I try to avoid quoting dead Russians, but Trotsky wrote that Lenin “‘thought in terms of epochs and continents, where Churchill thought in terms of parliamentary fireworks and feuilletons (gossip).” The contemporary Left should do the same.

Idiom: Let’s take these one at a time. There seems to be a tension between this citation of ‘the unfulfilled promise of enlightenment’ and what you describe as the illusions of social democracy, no? Or does the public sphere take place otherwise?

BS: Perhaps, “limits” would have been a better word to use than “illusion.” The social democratic gains won by working people, especially during the “golden age” of the post-war period are very real and not illusory. But still, it is rather depressing to think that the bureaucratic grey of the welfare state, with all its contradictions, should be the highest aspiration of human civilization.

My own personal political perspective is animated by the aspiration for socialism after capitalism, not just within it. I’m not sure if anyone or any publication that doesn’t subscribe to this idea can be called “radical” (which after all is from the Latin word radicalis — “of roots”). The question of how to get from here to there, with the traditional social forces that the Left have relied on largely demobilized and shattered, is a political one that I hope Jacobin can help grapple with.

Idiom: I’m fascinated by what you describe as the libertarian quality of the socialist ideal. Can you speak a little about the unlikely marriage of these two terms?

BS: There has been an association, a well-warranted one given the experience of the 20th century, of socialism with statism and authoritarianism. Socialism is about precisely the opposite! It’s about extending the democratic gains we’ve won in the political realm into economic and social ones in order to bring about a condition “in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.” Chris Maisano and Peter Frase’s pieces in the Winter 2011 issue of Jacobin are really good examples of socialists thinking about life and labor in ways that wouldn’t mesh well with the orthodoxies of either social democracy or Stalinism.

“Libertarianism” as popularly construed has been deeply ingrained into the American pathos. The rugged individualism, “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” mentality belies the fact that for most the American Dream is a lie. And for most Americans class struggle for better wages and living conditions in the short-term and movements for structural change in the long are in their self-interest and would enable them to live richer, and yes, more free, lives.

The left shouldn’t cede the language of “freedom” and “emancipation” to the right. Naomi Klein at a panel hosted by the Platypus Affiliated Society critiqued Milton Friedman (author of “Capitalism and Freedom”) on the grounds that he was a “Utopian ideologue,” mentioning that she didn’t think that there was any great need for “grand projects of human freedom.” If someone holding these views — however commendable her work — is at the forefront of radical politics today, we have problems. It’s a weird brand of “radical liberalism.” If she doesn’t want anything more than a re-heated Keynesianism, what separates her from the left-wing of the Congressional Progressive Caucus besides a tactical affinity towards Zapatistas and militant street protests? How far has our political imagination shrunk?

Oscar Wilde via toptenz

Idiom: And ‘as internationalists and epicureans’? Talk a little about the gourmet character of the new international.

BS: Everyone on the left likes to describe themselves as “internationalists.” Historically it’s been more of an aspiration than a reality, perhaps, but we try as well. And a rather surprising amount of our subscribers and some of our contributors are based in Europe, so maybe we’re succeeding.

More likely though this “success” is a reflection of the fact that the political problems we are dealing with have been pretty universally felt, especially in the “advanced capitalist world.” We’re all dealing with the decline of the old parties and unions and other organs of working class political representation. We’re all dealing with austerity and the neoliberal offensive and though some of the peculiarities of the United States, like our historic lack of a mass labor party and the “ideology problem” I mentioned, make the situation even more acute here, I like to think that we’ll be publishing material of universal interest.

The “epicurean” moniker is a bit more novel. So many of the survivors what Perry Anderson likes to call the “vanquished left,” are, for lack of a better word, humorless. Or at least their politics appear that way from the outside. Yeah, there were yippies and there are still Anarchists busy with street theater, art collectives, May Day caroling troupes, or whatever the fuck they’re doing with their spare time, but serious “scientific socialists” have been a pretty dreary bunch: more ascetics than epicureans. The fact that the Stalinist-era bequeathed to the world both trashy “proletarian literature” (though I’ll go to bat for Mike Gold any day) and “socialist realism” is telling.

A friend of mind, Adrian Bleifuss Prados, once mentioned that anarchists, the more politically problematic ones especially, are the only radicals who are producing consistently humorous and emotionally stirring literature. I tend to agree. There is something oddly admirable about meeting a woman whose been a member of the same Trot or Maoist micro-sect since the 1960s (if you don’t mind accepting a “party” newspaper printed on recycled toilet paper and debating the New Economic Policy, you’d probably hear a good story of two), but also something a bit depressing about it. It’s like the existence of these bat-shit crazy sects are living monuments to the failure of the left in the 20th century. Sure, one may argue that there’s a contradiction between railing against the smirking irony of postmodernism and telling people selling Workers Vanguards in the pouring rain to lighten up a bit and consider the effectiveness of these old models, but I don’t think so.

I think we’re creative enough to deal with our political problems and recreate a left that doesn’t recall the drabness of the past or represent some sort of apolitical, nihilistic revolt. Hell, we’re radicals, we’re supposed to be the avant-garde, not positioning ourselves as the conservative opponents of a constantly revolutionizing capitalism. We’re supposed to be spreading the gospel of what’s possible, of what can be made out of the present– dreams, not nightmares…

People forget that Oscar Wilde was a socialist. The individual pursuit of sensual pleasure is a pretty damn admirable task. “Anti-consumerist” forces and the crazy wing of the environmental movement would do well to remember that the problem of the 21st century is how to enable more people to enjoy fruits of our social labor. I have my share of arguments with the Spiked! crew, but I’ve heard worse ideas for a political slogan than “Ferraris for all.” That’s the “gourmet character of the new international.”

Idiom: Nothing’s too good for the working class. Terry Eagleton made a similar point about Wilde recently. Other people were fighting for socialism, but dammit, he was living it.

Isn’t there something slightly contradictory, though, about demanding that politics, or ‘political’ people, be funny, or tasteful? It seems to presume that our politics exhaust us, that there is nothing for us outside of our very specific political commitments. Maybe the woman selling the Vanguard is an absolutely hilarious freelance saucier the five nights a week she isn’t making revolution.

Is it best to imagine we are political all the way down, so to speak, and hence the necessity of clearing a space for the finer things from within an all-consuming political practice? Or is it instead that politics is merely one of our many weekly or daily vocations, and that we can be funny at other times and in other places?

I ask because I am, of course, in sympathy with your point, but part of me feels like this is really an editorial problem, a function of us worrying that our publications are too damn pretentious and unfun, rather that it is an actual feature of the politically committed in their natural habitat.

BS: Well, let’s take a step back. I get what Eagleton was saying– Oscar Wilde was engaging in the arts, had enough time for leisure, so when he wasn’t being hounded by the offended moral sensibilities of late Victorian society, he was living a life to aspire to… but one of the flaws with anarchism, or at the New School, is the mistaking of lifestyle with politics. They are very different things. If the goal is structural change, one can’t just find some “liberated” space and begin a revolutionary “everyday life.”

And it’s not so much that the attitudes of individual activists need to change, it’s a wider culture of the Left and the culture of the micro-sect. The internal structure of these groups — the conformity to a party line, the bastardization of democratic centralism, the lack of internal debate and discussion — is the reason for lack of vibrancy. A condition like this would be a bit more tolerable if we had a party like the Greek CP that, for all their flaws, actually was a political force, but we don’t.

So, it’s not just about clearing the way for the “finer things within,” but creating a political program that still has something positive to propagate. I guess one can say there is something similar to this critique in the work of some of the more eccentric “anti-authoritarians” on the Left, but my suggested solution is quite a bit different. I’d like to think that the solution to the humorless micro-sect is more centralization, not less. Instead of a million different “parties” with a million different lines, how about a genuinely democratic and vibrant Party that allows for permanent factions and debate. I can’t shake my inner Leninist despite my disgust for “Leninism.”

I think about the October 2nd “One Nation” rally in Washington DC or any anti-war demonstration we have in the city. A young activist is confronted with dozens of different papers, dozens of different messages; all oozing with marginalization and failure… it’s confusing and a waste of resources and a projection of ineptitude and marginalization.

Mike Gold nee Itzok Isaac Granich, via wiki

It might be a bit naive to think that a platform of reunification would do much for the Left. The project basically means bottling up the contradictions that formed the splits in the first place and hoping that in a condition of free debate the “right” line will win out. But still, I can’t help shake the feeling that SP-USA and Solidarity and FRSO, for example, do pretty much the same thing and shouldn’t be wasting paper or money printing three newspapers….

The Left could desperately use a coherent “oppositional pole,” an organization hegemonic enough that other leftists would be forced to orient their politics around it, an organization hegemonic enough to be a flag for the newly politicized. I’m straying from your question a bit, but I was just wanted to make clear that I don’t call for a revolution in consciousness, or in the culture of the Left, without significant structural change.

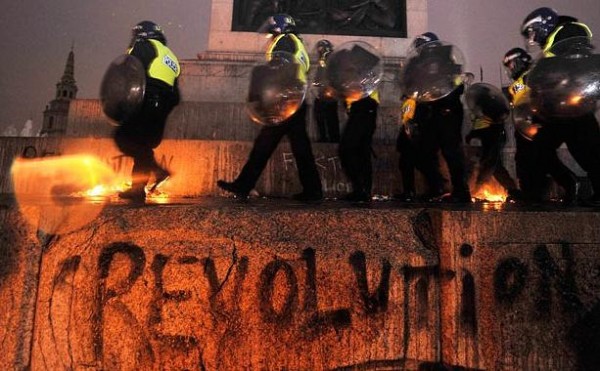

Idiom: Granted, but given the erosion of the historical mass basis of the left, both as a coherent identity position and as an organization, where are we to turn? The response has recently been the new social movements, or to cultural formations, which may be the last idiom common enough to serve as the basis for the sorts of structural consolidation you describe. This is sort of a chicken/egg conversation insofar as I am curious if you think the organization or the lived experience comes first.

BS: Unfortunately, I don’t have a blueprint, but I refuse to churn out the old leftist cliche about not “believing” in blueprints. I do know that this is the primary political problem facing the left today and the good thing about political problems is that they can be resolved. There just doesn’t seem to be that much debate and discussion going on now. Even mentioning “revolutionary strategy” at the present conjuncture seems a bit absurd for a lot of people.

I’m glad the new social movements exist, but they can’t replicate a revolutionary party. So I guess I’m an “egg” man. Whereas, a lot of people in the left argue that by supporting struggles from below we’ll reach a point where a party will emerge naturally from a new political environment, I think it might be necessary to talk seriously about a re-foundation of the left today. There’s no reason why the members of the left broadly subscribing to the same politics shouldn’t be in the same political formation. This might sound be “vanguardist,” but I think it’ll be a catalyst and at least create a pole hegemonic enough for anti-capitalists in North America to orient their politics in relation to.

We need the organizations in place to make gains when objective conditions change. We need organizations that don’t duplicate each other’s efforts. I look at England, where there was an admirable student upsurge and some momentum against austerity, but the left has sort of squandered this energy by having each tiny socialist party set up their own “front group.” Why exactly does the Socialist Party of England and Wales need to have their own group to compete with the Socialist Workers Party’s one? (And why exactly are we hiding our politics behind these euphemistic “front groups” anyway?)

It’s still going to yield a marginalized, largely irrelevant left in the short-term, but that’s a step up from marginalized, fragmented, and largely irrelevant, right? And after that we need to be patient. There are no short-cuts. The name of the game is overthrowing class cleavages, a fixture of human society since the Neolithic Revolution… this is a multi-generational project and we have a long way to go to even get back to where the movement was a century ago.

Idiom: Speaking of the impossible, I’m pleased to see that Jacobin appears in print. How do you manage that?

BS: Our printing costs, for an all glossy, all-color magazine are relatively cheap. The rest of the draw goes to bookstores… our sale rate exceeded expectations, but you don’t actually make a ton of money here (even The Nation only sells a couple thousand a week off newsstands). We get some revenue from advertisement and donations and manage to hover right around even.

When I tell people some of the other Jacobin contributors are better political thinkers and writers than I am, I’m not being modest. I just have other more bourgeois, entrepreneurial gifts that facilitate the project.

Soliciting good advertisers is one of the hardest part of the process. I’ve been procrastinating and delaying getting our new ad kit out in time. We offer a relatively good deal, cheap rates and people forget that magazines are passed around and read by multiple people…. still the economy sucks.

Idiom: I am in total sympathy with the having of bourgeois gifts. It is funny, isn’t it, how rare basic managerial skills are on the left… what are your hopes for the magazine in the future?

BS: And the left was once known as the total opposite — a tightly coordinated, highly disciplined bunch…

At the moment my goal is modest: an eight issue run at as high a print-run as is financially viable. Hopefully, we’ll have made at least one “intervention” of note by the end of the project and hopefully the issues we grapple with will at least make a dent in the consciousness of the “vanquished” left. A bit short of storming the Winter Palace, but we have to start somewhere, right?

I want to keep the style provocative and engaging and very visual, but I also want us geared towards politics and economics. We’re a young bunch, so we’re producing less on the economic end than I would like, but I expect this to change in the near future. And politically, I’d like to deal thoughtfully with what the left’s strategy should be at the present conjuncture… questions beyond my facilities as a writer (at the moment, at least), but there’s plenty of people worth publishing.

There’s a niche for this kind of material. I don’t really see anyone doing what we’re doing and I’m not sure whether I should be proud or disheartened by that. I do know that if the response to our haphazard launch is any indication, there is a market for what we’re producing (the same could be said of scatological porn and Thomas Friedman books, but that’s neither here nor there).

Idiom: If you could be advertising supported would you?

BS: Absolutely. I’d run public service announcements from the Republican National Committee and/or local drug dealers if it didn’t change the editorial content of the publication. The only goal is packing each issue with the best material possible and disseminating that material as widely as possible. We have to deal, at the moment, with the world as it is.

]]>

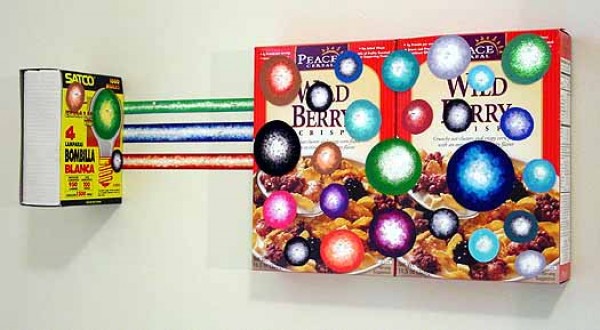

Scott Keightley, Installation View, 2011 via Recess flickr

Late last week Stephen Squibb sent some questions to Scott Keightley. Scott had an opening at Recess. When he got back, he sent answers.

Idiom: How does the show at Recess relate to your previous work?

Scott Keightley: That’s a hard question. I am embarrassed by a lot of my previous work, but I love some of it, and I’ve learned from all of it. I don’t know the answer to this question.

Idiom: Can you talk about the interaction between social practice and object production in your work? Why build a sculpture next to a skate ramp?

SK: Skateboarders are the most innovative artists of my generation. In this way, the ramp itself is a sculpture. I think your eyes are like a catapult for your heart, and skateboarders embody this idea. Also now that I’ve pulled it out of the wall it looks like a Robert Smithson, only it’s better because you can skateboard on it.

Idiom: What were the communities and identities that informed your sense of self as you grew up? Which of these inform your work today?

SK: I have always felt like an outsider. A willingness to get weird and be honest about stuff is what I have always valued and continue to value. That and a healthy capacity for fantasy, which is a veil but a very beautiful and important veil and also a mirror and a window.

Scott Keightley, Installation View, 2011 via Recess flickr

Idiom: Talk about Waltham, ‘America’s first industrial city.’

SK: Under the Reagan administration a lot of mental institutions in Waltham were shut down and residents were thrown into the street. Now there is a really high population of crazy homeless people in Waltham. I always liked to explore the abandoned train tracks and factories and old bridges along the Charles. In the Spring time it is very beautiful there.

Idiom: How would you define ‘natual,’ or ‘organic,’? How do we know? Or is it not about knowing?

SK: The words ‘natural’ and ‘organic’ were both used in the press release for this residency. Those were not actually my words, but I think they are totally relevant conceptually. The whole show is kind of about pollution and embracing it.

Scott Keightley, Installation View, 2011 via Recess flickr

Idiom: Is the artist responsible for making a kind of social commitment?

SK: Well, I don’t know exactly what kind of social commitment you mean, but I’d say that social responsibility is important in general, and that by making art we benefit society at large. Artists are only people, although their work is sometimes extra-ordinary given the nature of art. In many ways art has to go through the artist, and being a good artist means being open to that. We should be like the antennae of society and culture, always feeling forward in the dark.

Idiom: Do you feel repressed or emancipated by the title of artist? Would you prefer something else? What would it be, if it was how everybody spoke about what you do, and it could be anything at all?

SK: Emancipated.

Updated 2/9

]]>

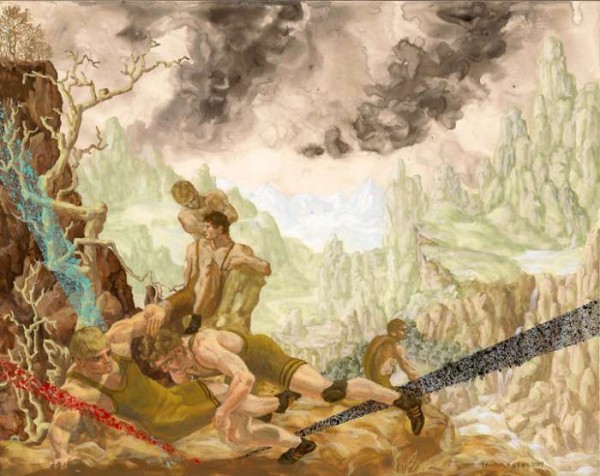

Larissa Bates, Shark Group after George Stubbs and Sargent, 2010. Via Monya Rowe

Late last year, a panel entitled Macho Man, Mother Man: Rethinking Masculinity with Geoffrey Chadsey, Leidy Churchman, Thomas Lax, Hudson Taylor and moderated by Colleen Asper, convened at Monya Rowe Gallery in conjunction with Larissa Bates’ ongoing Man Enough. What follows is a pastiche of transcriptions, emails exchanged ex post facto, and prepared statements. It is an attempt at documenting a small part of an extensive and many layered conversation.

Larissa Bates: How concepts of masculinity connect to a sense of self worth, power, psychology, and affect family structures are of particular meaning to me. My own interest in masculinity and male gender scripts grew from being raised by a single father during early childhood. With the exception of having the privilege to choose an alternative hippy lifestyle, my father fit the sociologist Erving Goffman’s 1963 normative prescription for masculinity.

And I quote Goffman:

In an important sense there is only one complete unblushing male in America: a young, married, white, urban, northern, heterosexual Protestant father of college education, fully employed… and a recent record in sports.

Having grown up with the privileges and limits of this heterosexist, racist, class-ascribed masculinity, my father suddenly found himself occupying the marginal role of young widow and single parent. What were the dominant cultural models of masculine grief at the time? He may have sublimated his loss in terms reflected in constructions of masculinity—the man as utterly self-reliant, stoic, and independent. He dug a hole in a hill, built a kind of cave house, and renounced electricity and indoor plumbing. In essence, he became a devastated cave man.

There was a dearth of cultural images to reflect the complexity and depth of his newfound role, nor images to portray how I perceived him. The heavily bearded, lumbering 6 ft 4 inches of his stonemason’s frame came to symbolize, among other things, nurturing, comfort, and care, to my young self.

Virgin Marys proliferated around the necks, above the doorframes, and upon the bed stands of the Costa Rican relatives of my Mother’s family. Mary, eternally clutching baby Jesus to her bosom, seemed the pinnacle of nurturance. It also seemed that what my father and I needed was our own creation myth, starring our very own Virgin Mary Man. This was how the MotherMan character was born into my paintings.

Because I was in charge of ascribing MotherMan’s characteristics, I could make a kind of super-human deity. Thus the MotherMen are the very epitome of nurturance and benevolence, whose presence calms the neurosis of all those who surround him. He simultaneously embodies the giant physicality of my father—only updated into a young wrestler. I don’t think my father took much solace in my supposed paintings to him, but they provided a romanticized reflection of my experience—and one I desperately needed.

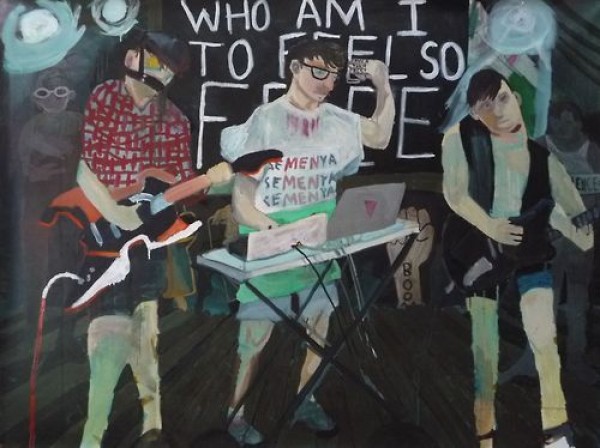

Celeste Dupuy-Spencer, MEN (Who Am I To Feel So Free), 2010. Via the artist.

It would help to define our terms for the evening’s discussion of masculinity. However, it is difficult to define masculinity because of the given mutability of gender as it relates to culture, race, class, and sexuality. Furthermore, masculinity can be understood through a variety of structural lenses. The conservative ideology of masculinity as universal, unchangeable, and largely connected to biology, varies greatly from perspectives of feminist theory, queer theory, or the Men’s rights movement, which postulates men as mutual victims of patriarchal structure, just to name a few.

Leidy Churchman: As a painter working with queer images, and as an artist that makes videos that integrate paint into the process, I’m interested in what the act of painting accomplishes as a piece of gender performance. It’s possible to see Pollack as sort of taking back his masculinity from the press by doing his action painting. For me, I feel like I’m bringing whatever I want to that place; if it is seen as something really masculine, then that’s as much about perception as about the reality of the action or image. I’m always interested in dressing bodies in this respect, asking the question of when they become bodies, or when they function as landscapes. Are they figures? Are they people? Are they dead? Are they alive?

Celeste Dupuy-Spencer: I am a painter too, and I use un-stretched canvas as a surface. Looking at art history as an art-historical painter, one sees that it is largely the painting of men doing masculine things. I am trying to take the gender question out of it completely. Once gender is gone people automatically assume a masculine focus but honestly, it is not something I really think about in terms of myself or my painting. I feel like I have no say, in the end, in how I or my paintings are perceived — if that is masculine or otherwise.

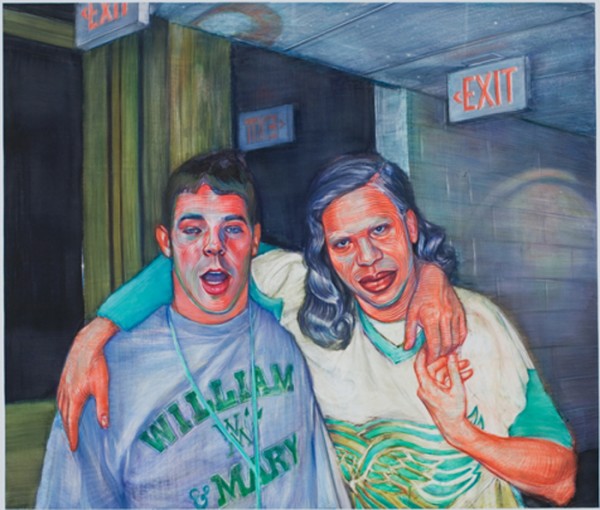

Geoff Chadsey: I’m a drawer. Kind of a backdoor painter. But I think in terms photographs. I draw photographs that I nab from online chat sites. They are other people’s self-portraits. I tend to morph them a bit, change the hair etc. I think we are, all of us on this panel, in one sense invested in breaking down masculinity, but we are also pursuing it, in another.

Geoffrey Chadsey, William and Mary, 2008. Via Jack Shainman

Thomas Lax: I have come to believe that there is a real indeterminacy involved in gender. I have been thinking a lot about Adrian Piper, who is thinking about the impossibility of locating what gender might mean, and moving away from the visual. Gender might be a way of naming temporality, loss, waste – gender is one way these things are lived and experienced. I recently did a show – VideoStudio: Changing Same – that drew an analogy between time-based-media and experiences of gender.

Hudson Taylor: I’ve been involved with wrestling for the past 19 years; it defines a lot of who I am. I grew up with a very strong vision of masculinity, not unlike the 1960s one Larissa outlined. It was always clear to me how I had to act, as a man, as a wrestler. The more developed my brain become, the more I pushed against that. As a coach, I am in an excellent position to offer a broader understanding of what it means to be a man to my athletes. My work as an advocate for LGBT issues really began with word consciousness – my teammates’ word choice bothered me – but I felt as a captain, as an all-American, I had a responsibility to try and change things. In college I put an HRC sticker on my headgear, which caused some stir, and did an interview with Outsports which led to about 500 emails from young athletes, parents, and just people in general who grew up with a really repressive understanding of masculinity and its place within sports culture. It was those emails that pushed me to become the ally I am today.

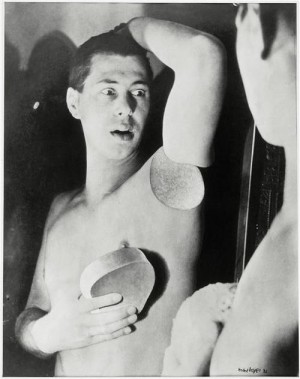

Herbert Bayer, Self-Portrait, 1932. Via Thomas Lax

Geoff: I was joking that perhaps the dominant masculine figure in society today is Sarah Palin.

Hudson: How are you reading masculinity?

Geoff: Hanging out of a helicopter shooting things; pitbull in a skirt.

Colleen Asper: It’s complicated though because that’s an example where masculinity becomes associated with conservative values that we position ourselves outside of.

Geoff: Masculinity is clearly an aspiration myth for this culture, and it’s considered attractive to see women occupying those roles, more so, perhaps than it is to see a feminine man. There is something so amazingly androgynous about someone like Tilda Swinton, it sort of makes her otherworldly.

Celeste: That hasn’t been my experience with female masculinity. Whenever I am forced to experience my own masculinity it’s typically pretty derogatory. I have trouble thinking in terms of what is more masculine, what is more feminine. I’m not sure it’s a really helpful place to go. We have these words to describe things, but what they are are starting points.

Colleen: Should the goal be access to institutions? or to dismantle them?

Hudson: I think it is a both/and rather than an either/or. At some point there has to be a redefinition of what it means to be masculine, of what it means to be feminine. Masculinity is whatever you perceive it to be. You call it masculinity, it is masculinity.

Geoff: Its a very tenuous thing.

Colleen: A constant, unacknowledged performance.

Leidy Churchman,Three Beards, 2007. Via Horton Gallery.

Geoff: Did we ever get at “masculinity”? I’m assuming we all have different takes on whatever that is, masculinity, and maybe we could struggle more to define what it is, or isn’t, even if it’s a shifting target. Gender is an irritating stereotype and yet there they are, them words: masculine, feminine, male, female, gay, straight… somewhere in there we locate ourselves, the gray areas. Gender with a Gaussian blur. As a self-identified (but hostile when identified by others) effeminate gay man, I find “masculinity” fucking tedious when used in a sentence, and yet, also as a gay man, I have to admit that there are many many attributes covered by that term (now I am mashing the term masculinity with macho) that turn me on. Sexuality doesn’t always make the best politics, and obviously “masculine” and “feminine” are relative terms, requiring each other to make sense. I tried to talk about effeminacy as an accusation, an attribution of lack, while pondering over it also as an attractiveness– a theatricality that maybe is just conflated with youth. Is macho an exorcism of the effeminate?

I heard a quote today, from someone who could not attribute the source, that goes “women are, men become.” That’s just another way of saying female = nature, male = culture, a stereotype we rolled our eyes at back in college, right? It could easily go the other way: men are, women dress up, I am thinking of (macho) modern art’s suspicion of ornament… But for this discussion I like how the first quote points out the willfulness of masculinity– the mannerism, costume, affectation, rehearsal, right of passage, the heavy lifting, the cutting away (like the image Thomas sent earlier)– a striving for some abstraction– one obviously that has quite a bit of power and bite to it.

Thomas, you used the word “opacity” (a word I love) repeatedly… so if we cant see through this thing, this term, this body, can we see around it, or start to describe its boundaries? what are marginal or subversive masculinities?

Larissa Bates, Five MotherMen Wrestlers with Laser Beams After Tobias Verhaecht, 2009. Via Monya Rowe

I keep going back to sexuality, because that’s mostly where I do my thinking (in circles). Brokeback Mountain — many gay men (and women) mooned over the spectacle of two (macho) men falling in love alone at the outskirts of society. Subversive? and yet most of the emotional swelling of the film was focused not on the Jake Gyllenhaal character who struggled to express his desire and ended up dead in a ditch, but on the Heath Ledger character whose (alluring) tragedy was his inability to express or commit to his love or lust: opaque to others, alone in his trailer, hugging his now-absent lover’s empty shirt. Willy nelson croons, and the audience swoons as the macho goes sentimental. His paralysis — does it make us feel… motherly?

Thomas: I brought up the idea of opacity in the context of how work by a generation of black conceptual artists — Lorna Simpson, Glenn Ligon — was received in the 90s, i.e. their work figured black subjects and was then understood to be “about” identity politics, equal representation and uplift. I think I used opacity to describe how in their work and work by other artists, black bodies often fail to signify in the open-ended ways that other bodies often do. The writer and theorist Edouard Glissant speaks about the idea of opacity in a different way. In Caribbean Discourse he describes “the right to opacity,” which I understand as a representational response to the ubiquity of the image/spectacle of the subaltern body in pain.

]]>

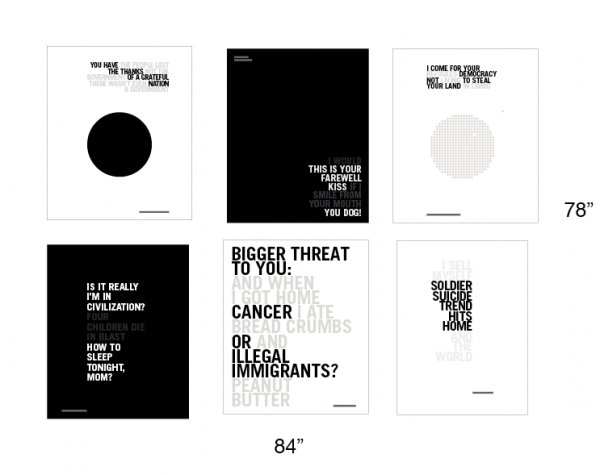

Michael Perrone, Billboard, 2002. Via the artist.

Michael Perrone is a Brooklyn-based painter and sculptor. He has mounted two solo shows at Michael Steinberg Fine Art in New York City: Home and Away, in May 2006 and The Last Picture Show , in September 2008. His work has also been featured in The New Yorker , Elle Decor , O at Home, and Time Out New York. Debora Kuan visited Perrone’s studio in Red Hook recently to discuss the trajectory of his work, why he feels exuberance on the New Jersey Turnpike, and the power of an empty room. The conversation continued over email in the week that followed the studio visit.

Debora Kuan: I see a lot of Precisionist ideas in your work. Can you talk about that? Are you interested in celebrating industry, modernism, or urban America?

Michael Perrone: Yes, early on I felt a strong kinship with many of the Precisionist painters, most notably Charles Sheeler, Rawlston Crawford, and Niles Spencer. I can’t remember exactly when I became aware of them; however, I’m fairly certain that I had already been engaged with that way of painting before I knew about them. At first, the similarity was mostly the visual language: the straight-edge pencil line (which I would often leave or re-articulate on the surface of the painting), the simplification of shapes and the flattening of the shapes by reduced value modulation, the use of muted colors, and the overall abstract quality that coexisted with the representational image. Once I was made aware of the Precisionists, I felt completely in line with their interests, as if I had been hanging out with them in the 1930s. Additionally, I was living in Pennsylvania at the time and studying with John Moore, whose work was also influenced by these artists, and both these factors further enhanced my connection with them.

During this time, while at graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, I became more focused on the industrial landscape. This was somewhat inspired by driving along the New Jersey Turnpike, from NY/NJ to Philadelphia. While driving I became very interested in the industrial forms: the factories, the billboards, the water towers, the high tension wire towers, even the cell phone towers which are disguised as trees. I began to celebrate these industrial icons in my work. The paintings became amalgams of different places: a water tower from here, a retaining wall from there, specific factory buildings and made-up ones too. I was trying to revel in the man-made world and thinking about these structures and forms as a new sublime. This interest grew, and in the work I would play the ‘natural’ elements against the man made elements. I was trying to question notions of beauty by imagining a future in which we would have forests of water towers and actually be content with that. As this idea evolved in the paintings, nature vs. the man-made, I began to paint the competing parts in different ways. It seems like a simple idea: I painted the ‘natural’ elements with a thick, textured, more tactile paint quality, and the man-made elements with a harder-edged, slicker, and glossier surface in an attempt to mimic the machine-made.

Michael Perrone, Geroge's, 2007. Via the artist.

DK: I think of you as a painter with a very distinct color vocabulary. But your color values—which are exuberant and bright–appear almost radical in today’s economically depressed climate. You seem to be painting defiantly against the prevailing mood, which I find very interesting. For instance, the colors in your geometric abstractions remind me of Peter Halley’s conduit paintings, but he began those in the Eighties. It seems quite another thing to be painting ecstatically bright abstractions now. Can you talk about those choices?

MP: My initial color decisions came out of two specific, non-conceptual places. After my first semester of graduate school, I began to make work specifically to upset my inner aesthetic sensibilities. I started to paint with bright, highly saturated colors as a way to do the opposite of what felt natural and comfortable to me: up to that point muted colors, inspired by the work of Giorgio Morandi. I basically grayed down everything. I was a value painter. For some reason, these subdued colors felt right to me. So that’s what I used and I managed to get pretty good at using those muted colors. In an attempt to upset myself, to force myself to do something different, something that I wasn’t good at, I began to use highly saturated, bright colors. Interestingly enough, this development coincided with my appointment as the teaching assistant for a color theory class (largely based on Josef Albers’ Interaction of Color) during the second semester of my first year at Penn. These two events were coincidental, but they forced me to spend that semester intensely engaged in color.

Michael Perrone, Abstract 01, 2008. Via the artist.

I was also using One Shot sign painters paint. These oil enamel paints are liquid and come in cans. There are many colors available… many that are at once bright, but also carry with them a nostalgia. For instance, these are the paint colors that your old high school gym lockers, metal school desks, and chairs were painted with. I began using these paints largely for their fluidity, and for the fact that it dried with a high gloss surface. These paints don’t mix very well, so I was often painting directly out of the can, and painting the shapes with a flat, unmodulated solid color. Some people felt my paintings of this time were reminiscent of Colorforms (those plastic decals from the ‘70s). I guess the important fact is that I was not blending or mixing color, but instead playing one color off another. The visual language was more like collage then painting.

Michael Perrone, American Dream, 2003. Via the artist.

This was the spring of 2003, and my imagery at that time was based around the then looming war with Iraq. I did have some ideas about the celebratory colors I was using and how that conflicted with my imagery. Additionally though, I was interested in how the war was often discussed in terms of sports vernacular. The visual language I was using was very flat and graphic, much like what you would see on the side of a pinball machine–almost stenciled shapes.

After the Iraq War Paintings, I just carried the new color sensibility with me into the next body of work, which is the work we began our discussion with: the industrial landscapes and then the nature vs. man-made paintings. I still think it’s a pretty simple idea, but the highly saturated color I was now using was perhaps just another way for me to talk about the synthetic. Additionally, at this time, I was trying to expand my ideas of what beauty was and what a painting could be. So this new palette that I began to use was also a way for me to push my own limits of what I thought was acceptable for a painting, what I considered beautiful. Basically, I combined my old interests in architecture and the landscape (geometry) with the new interest of color and I came out with something that was more than twice as interesting from where I started. This cycle of learning something new and then infusing it back into my older interests seems to be one that I keep repeating.

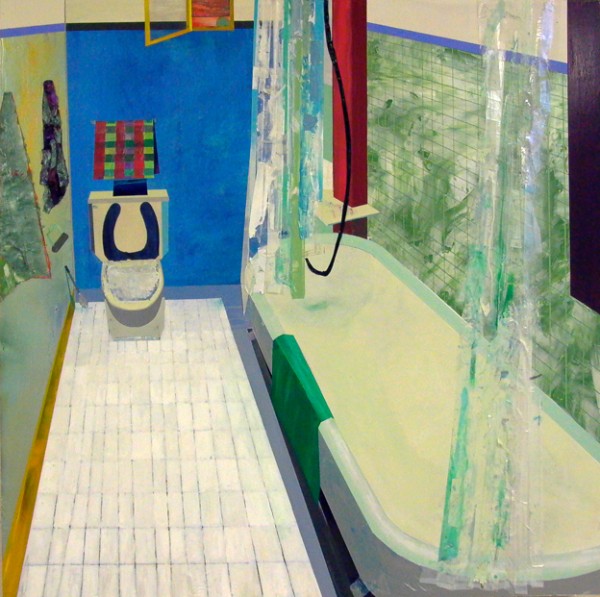

Michael Perrone, Iowa Bathroom, 2005. Via the artist.

DK: You’ve mentioned another aspect of your interior work that I find interesting—the collage effect. Can you talk about that decision with respect to your various Iowa interiors—bowling alleys, bars, diners, etc.? I’ve been in all of those places, and realistically speaking, they look very different—much dimmer, older, dive-ier.

MP: After moving to Iowa City to start a teaching post as a Visiting Assistant Professor (The University of Iowa), I continued with the landscapes–now based on Midwest driving–and at some point I gave a slide talk at the University and a lot of people were curious about this painting that I had made in my final week of grad school, The White Room. This painting was different in that it was not an imagined landscape, but rather an interior of a specific personal place (the room where we held all of our critiques at Penn, which also had a ping pong table). That painting was a forerunner for the work that mostly comprised my two solo shows in New York: interior paintings of personal spaces or spaces that I spent time in. After giving that slide talk, I began to think more about why that painting sparked such interest in the audience. I also started thinking back to one of my professors at Penn, Alexi Worth, who had been very supportive of my landscapes, but also felt that they were too generic, that something was missing.

I wouldn’t say that I had any kind of epiphany at that point, but I can say that the comment from Alexi along with the interest from my Iowa colleagues naturally led me to try painting another one of the interiors. So, I did. That painting, Iowa Bathroom, set in motion my subject matter for the next three or four years.

Michael Perrone, Tunnel, 2004. Via the artist.

In many ways, when I set out to make one of these interiors, I do start with the intention of capturing some essence of that specific place. Yet, ultimately what often happens is that the composition of the painting is very general, only a handful of shapes and minimal information. I then start filling in the details with blocks of color and then patterns and then more specific details, which are often taken from my memory of that space. Sometimes, during the painting process, I will revisit the space and stop and look, take mental notes, etc. Other times, I am working from memory of that place, but I am also allowing myself a certain sense of freedom to just make a painting. Allowing myself to use any color, no matter how ugly, like gold, or any texture, no matter how ridiculous, like cotton balls or architectural grass.

The places you mentioned–George’s, The Hamburg Inn, Colonial Lanes–I suppose in the hands of another painter (say, Edward Hopper, whom I love) would be handled in a more somber way. But for me, these places were places of great fun, and I suppose although I feel my paintings have some melancholic qualities to them (unpeopled stage sets waiting for action), my experiences in these places and my experience painting is one of tremendous joy.

Michael Perrone, The White Room, 2004. Via the artist.

DK: I’m glad you mentioned that—it’s true that an interior tends to evoke a kind of solemnity. After all, a room’s very purpose is to house people, and there aren’t any people in yours. I think that’s what rounds out the faux naivety in those scenes and gives them such depth—the interior naturally suggests the inner life and carries all the humanness that comes with inhabiting that space.

MP: The faux naivety that is sometimes associated with my paintings is completely unintentional. I do think I am an optimistic person, and idealistic, but my painting process is very much intuitive and impulsive. I basically make it up as I go. So the awkward scale shifts, the skewed perspective, the other elements in my work that might resemble a naive artist’s approach are not necessarily intentional. What is intentional is the fact that I give myself permission to make a mark, or create a shape, and then let it live, even if it is off or not completely accurate to the rules of linear perspective. I let it live and then modify the painting to correspond to it. I solve the puzzle as I make the puzzle.

Debora Kuan is a poet, writer, and art critic. Her writing on visual art has appeared in Art in America, Artforum, Culturehall, Paper Monument, and elsewhere

.

And Longing Is No Longer Sleeps, 2010.

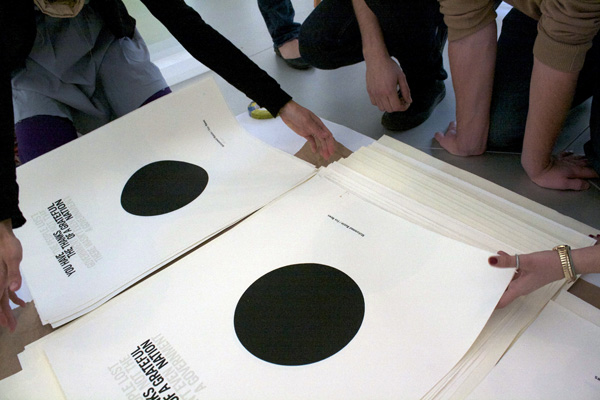

The following statement was produced as part of Conversations on the Line, a project within the exhibition How To Do Things With Words at Parsons. Organizer Huong Ngo and artist and curator Melanie Crean emailed with Stephen Squibb to continue the conversation.

On Collaboration: “How To Do Things With Words”

Authors: Melanie Crean, Huong Ngo, Grant Noel, Or Zubalsky

Contributors: Rachel Bernstein, Gabrielle Guglielmelli, Julio Hernandez, Andrew Persoff

Its really hard to hear, broken up and such

Can people hear me?

I just hear some noises of voices

The sound is broken

I can’t really really hear you

Your words are coming in and out

Your voice is broken

No its broken, broken for me too

This marked the beginning of a series of online conversations about language, power and systems of education between a group of ten artists and design students from the US, speaking with ten medical students from Baghdad during the summer of 2010. As it quickly became evident, a larger conversation was actually taking place, about the nature of cross-cultural communication via contemporary technologies.

Though initial communication took the form of asynchronous, boisterous and chaotic chats, members of the group shared information that was remarkably intense and personal, leading to an unusual intimacy forged between people who had never met each other. Perhaps it is sometimes easier to say difficult things from a position of relative anonymity. Through the frustrating disruptions of technical and electrical failures, Iraqi students described how in pre-2003 Iraq, they were given a form in school to pledge their loyalty to the Baathist party. They could choose to do this, or drop out of school. Students were afraid to rebel, or even discuss their opposition in public for fear of violent retribution. In post 2003 Iraq, the students described an opposite extreme: because of the large number of political parties and the feeling that no one was ultimately in charge, many teachers proselytized for their political party directly in the class room. In contrast, an American student described a public school in the conservative South as imposing status quo- conservative, Christian, heterosexual norms, or “everything that we got from the rest of society and TV. It is a sneaky imposition, because it hides itself, and makes itself feel natural. If you disagree, then you feel unnatural.”

Conversations on the Line, 2010. Courtesy of Andrew Persoff

During the second part of the project, communication took on a markedly different texture: design teams worked in local groups, forming their own strategies to create a response based on the initial discussions. Rather than being about exchange across large distances, intensity was formed through collaborations negotiated with people sitting in the same room. A reflection of the collaborative process from one group:

“We, Me, We: As the youngest of 6 (youngest of 3, youngest of 2, oldest of 3…), I prefer plural nouns. The statement, “we are celebrating ______ (fill in the holiday) together” makes me glow inside. As a collaborator, these words are essential in the process of simplification, inclusion, and definition, but also elide complexity, nuance, and contradiction. The we in the case of our recent collaboration are students and artists from Parsons working on a series of posters and zines about the personal trauma of war and displacement and its portrayal in the media. Yet, the we began before that with conversations among students and teachers around the U.S. and Iraq, and before that with writers of headline news (the text of which was appropriated to contrast with personal stories of immigration), and before that with the many we’s it took to make a war; many wars, in fact, because like Lay’s potato chips, you can’t seem to have “Just One.” The binary opposition that we see as “me vs. you” is actually a problem of not seeing at all times that a we that exists for you at all times. The utopian potential for inclusion is a commodity of social media, but it is only as good as every member actively engaged in the process of making space for we.

Making we: Snacks, jokes, laughter. We have to be in the same room to do anything because to do something, you have to do nothing, at least for a little bit. Some of us have not been involved in the political side of art before, but working in a group made that new environment comfortable. There is a relieving factor in a collaborative effort that touches upon painful subjects. The hugeness of war is almost petrifying when approached by a single person, and attempting to communicate ideas that comment on it is something that requires many points of view. Not only because every person has different interpretations, ideas and skills, but also because the number of people present in a room helps to bear the heaviness of the subject. Silly as it may sound, the exchange of snacks and jokes affects the exchange of ideas directly.”

One of the most telling things about the experience is that it continues with incredible energy via the group Fantastic Futures which will continue the exchange and conversation between Iraq and the U.S. through the exploration of sound. So here’s to hearing more soon from a future fantastic…

Melanie Crean/Jordan Parnass Digital Architecture, Continuous Session, 2010. Via the artist

Stephen Squibb: How would you describe the sort of work you see this project performing?

Huong Ngo: The project, initiated and organized by Melanie Crean, began as a series of conversations among medical students at the University of Baghdad and students and educators in the United States (mostly from Parsons, Pratt, but some from other places in NY) over Skype about education, power, and politics. Melanie brought me into the project last spring to help structure the conversations and I introduced my former students to the project. The conversations began with anecdotes about our respective classroom experiences, and then branched into issues of human rights, women’s rights, politics, and daily struggles in post-war Iraq.

In the second phase of the project, we broke into 3 groups. Each addressed a particular aspect of human rights. The Iraq group focused on the reality of being a woman in Iraq, Melanie led a group focusing on the Iraq and US constitutions, and I led a focus on immigration. To realize the material parts of the project, I invited a group of Parsons students that I was teaching this fall. We collaborated on a series of posters that juxtaposed text from news headlines with personal narratives about immigration. They were screenprinted so that half of the text was nearly invisible.

Conversations on the Line, 2010. Courtesy of Or Zubalsky.

SS: How do these projects take place as works of art, do they demand a different approach from the artist?

Melanie Crean: For Conversations on the Line, I was interested to work in a more collaborative, process oriented framework. The project began with weekly Skype conversations comparing experiences in the class room, and went on to discuss student activism, the corporatization of media in the two countries, freedom of speech, and daily life in post-war Iraq. The conversations inadvertently began to address the nature of online communication: at once amazing for its ability to reach across cultural boundaries, but fraught with technical difficulties in an era of multiple software platforms and electricity outages. The live chats were underscored by a blog where the group could post questions for more thoughtful consideration. The participants later chose topics from the conversations to pursue in three artworks: the Baghdad project considered the reality of being a woman in post-war Iraq, one US project examined the representation of immigration in news media, and another investigated legal versus perceived speech rights.

HN: The nature of this project emphasized the process of collaboration, which is often difficult to translate into the final gallery object. As an artist, there is a negotiation between representing the process as faithfully as possible, making it as democratic as possible, and having a clear vision for the final project. For the audience, it is like a puzzle to decode what/where the moment of art is. Perhaps what is visible to the audience are artifacts of an action that has already occurred.

SS: What did you take from your experience working on How To Do?

HN: One thing that has been really difficult to capture is the process of collaborating with the students in Iraq and the ones in the US. It is at times difficult with language barriers and differences in creative process, but I have been amazed at how eager the students have been to engage one another. The best moments have been not when we are talking about political change at all, but sharing moments of our daily life–swapping youtube clips of videos that are popular among students, parsing out different expressions (“hurrah” needed a translation, and we discovered that “hhhhhhhh” means “haha” or “lol”). There have also been incredibly poignant moments when our Iraqi counterparts talked about car bombs that went off less than a mile from their homes and when the suddenly go offline because of power failures, both aspects of daily struggle that become much more palpable to us when in the context of a conversation and not simply read on the news.

Melanie Crean, Music for Shiloh, 2010. Via the artist

For me, it has been amazing working closely with a group of students here who have never really made art that is political. I was initially not sure whether they could feel real ownership over the project and connect with the text that they were working with. Midway through the project, I found that they were articulating what we were doing better than I could, and discovering nuances in the text that I had not. Now, these students and the same group in Iraq are part of the next phase of the project that is alluded to in our statement, called Fantastic Futures. This phase, which I am leading with Ali Saloom Abid, a med student in Iraq, is a series of cultural exchanges through sound that will be collected online in a way that anyone can share and experience.

MC: In reality, the project was a Social Sculpture, as inspired by Joseph Beuys, which existed on several levels. Beuys described all creative acts, including conversations, as forms of art that had potential for great social impact. In this project, amazing things happened at a range of moments: when students discussed the potential construction of the mosque in lower Manhattan, swapped YouTube videos of pop songs, and checked in after a car bomb went off a block away from the University of Baghdad. The impact of such events was all the more poignant when read via live chat with friends, rather than through anonymous, disembodied news headlines. The group continues to organize with the name Fantastic Futures, under the auspices of Ali Salim Abood and Huong Ngo.

On the whole, a lot of really good conversations were had and a great deal of coffee was consumed. For me, the impact was personal, in that the experience inspired a round of new projects, most notably an experimental video about the relationship between speech and memory.

And Longing Is No Longer Speaks, proof, 2010.

SS: Can you speak about the larger exhibition?

MC: The How To Do Things With Words exhibition provided a forum for artists exploring the relationship between speech and action. The exhibition took its title from the groundbreaking text by British philosopher J.L. Austin, who first wrote about the power of speech to create change or ‘speech acts’. Austin disavowed the notion of language as something that passively outlines the world around us, but rather described it as a set of practices that can be used to affect and create realities. Austin’s premise is that speaking itself contains the power of doing. In this sense the exhibition was a conversation about the power of speech. To facilitate this, I worked with Jordan Parnass Digital Architecture to design a sculpture called Continuous Session, that set the tone for the show by framing the gallery as an interactive space. The sculpture, assembled from rapidly prototyped plywood, referenced the design of the UN Security Council chamber, a room always left in reserve for meetings to defend peace. During the day, students and community groups made use of the space, and in the evening, a series of talks and performances explored the relationship between speech and immigration, revolution, protest, political humor and First Amendment rights. Urban studies students discussed the function of speech in the public commons. A woman on the verge of being deported held tea parties to try to garner press for her artist’s visa. Girls from a Bronx middle school who had been abused used the space as a safe haven for discussion.

In addition to the many talented artists who presented work in the show, (gallery works by Azin Feizabadi and Kaya Behkalam; Andrea Geyer and Sharon Hayes; Yael Kanarek; Carlos Motta; Martha Rosler; the Iraqi/U.S. Cross Wire Collective; Mark Tribe; and The Yes Men. Talks and performances by: Mary Walling Blackburn; Feizabadi; Kanarek; Huong Ngo and Hong-An Truong; and Tribe) I contributed several works from an ongoing series that explores the creation of political identity through speech. The projects pose two central questions: how does language function in creating our political identity at different points in our lives, and how do we then use language to affect change in different socio-political climates?

SS: What are the influences at work here?

MC: The projects drew from several influences. Louis Althusser’s concept of interpolation was central to all of them: the process by which we come to recognize ourselves in the way that the state, or dominant social and political norms, define us. This process of identification then creates identity. Culture identifies me, and I then become the ‘me’ that it has identified. How is this accomplished through language? How does it occur at different points of language development, with a child first learning language, with students trying to initiate change in their surroundings, with recent immigrants familiarizing themselves with a new political environment in a new language, or with the general public trying to adjust to a volatile political climate?

Melanie Crean, How My Son Learns to Speak of War, 2010. Via the artist.

SS: Althusser is fascinating in this context. What I appreciate about your work is how it recovers this line separating what liberates from what conceals precisely as a question, by a taxonomy of the different ways we practice language, and the ways it practices us. You have examined this ‘lexical politics’ through notation, speech, and the archive. Can you speak about each of these projects?

MC: The piece entitled Music for Shiloh is a series of visual scrolls inspired by Fluxus concepts of change and notation. I recorded my son Shiloh each month for the first two years of his life as he learned to walk and speak and express desire, thus constituting himself as an individual subject. The piece consists of five horizontal scrolls: the top most consists of twenty four representative video stills of the child learning to walk; the second depicts those same frames as individual paintings; the third as drawings and the fourth as dance notation of the movement represented. The bottom scroll represents the process of learning to speak in five acts of visual, musical, notation, analyzing the twelve minute audio track as pure sound (30 seconds from each month, available at melaniecrean.com/shilohsound. The piece will be completed this spring, when the visual notation will be interpreted by musicians and a dancer. The performance will be recorded with Shiloh present, documenting how this new performance evolved from his original actions, through the process of documentation, reinterpretation, and spectatorship.

SS: This dovetails nicely with your project documenting your son’s encounter with the language of war.

Melanie Crean, Shape of Change, archive, 2010. Via the artist.

MC: How My Son Learns to Speak of War was influenced by the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget’s concept that intelligence develops in a series of progressive stages. Children develop a concept of reality dependent upon their age, which they continuously reconstruct with higher order concepts as they mature. In this light, when is the concept of War first understood by an American child? How is that concept interpreted, where does it come from, and how does it develop? Beginning on my son Micah’s fifth birthday, just before his entrance into kindergarten, I began to interview him on video about his concept of War. Initial responses were mainly concerned with power animals, robots and playground altercations, but within a few months, questions concerning wars in Iraq and Afghanistan began to filter in. At the end of each session, I have been photographing him acting out and drawing his descriptions. This project is ongoing.

The Shape of Change investigates the concept of the archive. How can the desire for political change be expressed, recorded, quantified and visualized? How do these expressions change over time? Over the two year period of the proposed removal of US military forces from Iraq, beginning with the election of President Barack Obama, and ending with the formation of the new coalition Iraqi government and US midterm elections, I asked people across Iraq and the United States to describe their associations with the terms Change, Democracy, Freedom and Utopia. Responses ranged from banal and trite to unexpected and extremely moving. Phrases such as Oil Spill and Security rose and fell. Terms like Tea Party came into existence and continue to surge. The piece currently asks more questions than it answers, hovering in a limbo between a sociological design exercise and Robert Morris’ Notes on Sculpture. What relationship do patterns in a national conversation about political change have to sculpture? After taking some time to mine through the archive, I plan to create an artist’s book with the material, though the form of the book remains undefined at this time.

]]>

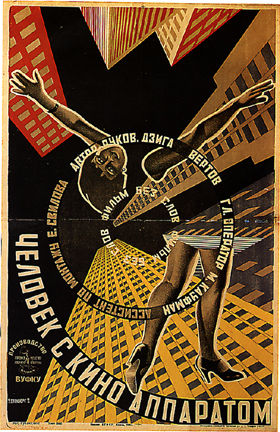

Dziga Vertov, Man with A Movie Camera, 1929. via Frieze

Tonight, John MacKay, Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures and Chair of Film Studies at Yale University, will be giving a lecture entitled: ‘Dziga Vertov and the Rhythm of the Proletariat’, at Cleopatra’s. The lecture is presented by Light Industry, in collaboration with the gallery, as part of their Couchsurfing series. MacKay is the author of Inscription and Modernity: From Wordsworth to Mandelstam, Four Russian Serf Narratives and numerous articles and translations. His book on Dziga Vertov’s life and work is forthcoming from Indiana University Press. Stephen Squibb asked MacKay a couple of questions in advance of tonight’s talk.,

Stephen Squibb: I’m fascinated by the title of your lecture. How did you first become interested in Vertov?

John MacKay: I first became interested in Vertov ca. 1993, when I saw Man with a Movie Camera. Later, when I started teaching, I realized that there was very little archive-based research on him or his work. That was pretty much the start of it.

My interest in Vertov isn’t just a matter of filling in gaps in existing research, of course. Working on Vertov enabled me to discuss four things that have long interested me: experimental and non-fiction film, the fate of socialism in the 20th century, Russia, and the idea of radical (left-wing) art as such. Vertov plunges you into all these themes simultaneously, which makes him both exciting and hard to write about.

As far as the “proletariat” and “rhythm” are concerned: when writing about Vertov (or indeed any filmmaker, in my view), one needs to find ways to do equal justice to history and to form. This is very hard, because the more seriously you attend to form, the more it can seem that the specific shape of the film (or other artwork) drifts away from its historical setting, or at least is connected with that setting only in a very mediated way. It’s in finding those mediations, which should selected with the aim of avoiding reductive readings, that the difficult work comes in.

Poster for Man With A Movie Camera, via WMU Photo

Vertov’s films are marked by (among others) two characteristics: an emphasis on the “documentary” depiction of workers and work processes (mainly industrial), and extraordinarily precise rhythmic organization of his footage (and later, of sound). The “formalism” of his work got him into considerable (though not lethal) trouble, as is well known. What justified this approach?

After digging into the film and Vertov’s archive, I found a couple of “mediating ideas” that helped me to organize my findings and ask some interesting questions: Etienne Balibar’s historical inquiry into the idea of the proletariat, and Karl Bücher’s “Arbeit und Rhythmus” (1896).

To put it simply, Balibar shows how the notion of the proletariat contains from the outset an inner tension between universality (i.e., conceiving of proletarians as everyone, as the multitude generated by capitalism’s homogenizing effects) and particularly (i.e., proletarians as a specific group (the industrial working class) with a particular, historically privileged relationship to capitalism’s most modern form). With Bücher, the issue becomes the estrangement of the body from work processes in the modern period, as signaled by the disappearance of work songs from the factory floor.

Vertov, I believe, tries to bridge the gap between bodies and machine rhythms, and between proletarians and non-proletarians (like himself), through a kind of rhythmic organization of sense data (visual, sonic) that will enable that “multitude” to emerge, at least on the level of perception. This organization is both musical (that is, high-cultural) and mechanical (i.e., proletarian) at once, insofar as it takes the individual film frame (a feature of cinematic technology) as its basic rhythmic unit.

The “bridging” is, of course, totally figurative, but it can be read as a imaginary solution to a real (social) problem, rather than (as is usually the case) simply an example of Soviet “machine fetishism” or something like that.

Dziga Vertov, at the shooting of World Without Game, via Visualrian

SS: Excellent. Is that the Balibar of On The Dictatorship… ? I think its interesting that Vertov attempts to fuse two kinds of rhythm as a precondition for the sort of figurative solidarity you describe, as it seems that this performs some fascinating assumptions about both proletarians and non-proletarians alike. Chiefly, in the case of the former, that her consciousness is exhausted, in some sense, by the nature of her work, by its rhythm – and thus she must be spoken to at this level. With regards the non-proletarian, it is assumed that she will either benefit from, or be in sympathy towards, this experience of proletarian rhythm, so long as there is some low-volume conceptual shadow-play going on somewhere to keep her entertained.

Is there, in this sense, a sort of structural condescension at work in Vertov? Which is more Zhdanovian, after all, a certain noblesse-oblige vis a vis the proletariat? Or an insistence on a universal capacity to appreciate essentially formal or conceptual work?

JM: Well, this is a really hard call. Your question brings into very clear focus one of the major problems in the interpretation of Vertov, and of Man with a Movie Camera specifically.