Amanda Ross-Ho, Invisible Ink, courtesy the Artist and Mitchell-Innes and Nash.

Amanda Ross-Ho’s first solo exhibition in New York at Mitchell-Innes & Nash offers a welcome weightiness – literal and otherwise – to a kind of funny-ha-ha play with the language of material and form. This is exemplified by the title of Ross-Ho’s exhibition, SOMEBODY STOP ME, a dry imperative that is both sarcastically self-deprecating and earnestly insecure. It’s a classic, cheeky Ross-Ho title, in perfect agreement with the names of previous shows at Cherry Martin, her Los Angeles gallery; HALF OF WHAT I SAY IS MEANINGLESS, NOTHIN FUCKIN MATTERS, and my favorite, Don’t Front (You Know I got Cha Open), stolen from the now-defunct hip hop group Black Moon. (fantastic ackronym: Brothers who Lyrically Act and Combine Kickin Music Out On Nations.) In truth, somebody shouldn’t stop her, half of what she says is not meaningless, and no, its not true that nothing fuckin’ matters. The show titles – colloquial double-negative statements whose ostensible responses amount to two empty assertions that cancel each other out – are an appropriate framework for understanding Ross-Ho’s seemingly disparate and mismatched objects. The use of positive and negative in language is echoed in the way Ross-Ho interacts with the space of the gallery’s white-walled architecture.

Take for example, Negative Carrier #7 (Yours Sincerely Wasting Away) (all works 2010), a nine-foot tall canvas drop cloth hung on the wall with the huge shape of a large format negative carrier cut crudely away. The negative space of the canvas frames the empty, white gallery walls, and attached to what remains of the cloth are a few everyday items – safety pins, rhinestones, a brass buckle. Approaching the object-ness of the cloth as one-dimensional by flattening it against the wall, Ross-Ho further subverts the material’s status by creating a negative space within it, which simultaneously returns it to its original two-dimensionality. Or does it? Perhaps it is simply that the canvas is a negative carrier. Of course! The words do actually say what they mean, but in effect, the work exists in suspension between negative and positive.

Amanda Ross-Ho, Negative Carrier #7 (Yours Sincerely Wasting Away), courtesy the Artist and Mitchell-Innes and Nash.

Ross-Ho also teases out notions of presence / absence and negative / positive through a strategic deployment of both scale and banal material. Administering Sabotage Through Craft is an enormous, almost grotesquely larger than life t-shirt – stained, torn, and hung shabbily on the wall – that calls attention to the absent body. The t-shirt claims exactly what the artist intends, making for a kind of physical manifesto that does the work of the words inscribed on it. On the wall next to the t-shirt is another sculpture that also grossly enlarges an everyday object – this time a ‘gold-plated’ sad-faced clown pin called Double Feature; inverted to show the backside of the pin, the hollowed-out clown face works as a double negative. In Heirloom Model with Scale Natural Disaster (Preserving Memories is What We Do Best), a shoddily-constructed foam core gallery model is elevated to a different status of objecthood by its gold metallic sheathing. Sitting on an old, paint-splattered art school-style stool and leaning against the wall, the sculpture is a (be)littled representation to the site in which the viewer stands, a kind of false monument to the white cube.

Amanda Ross-Ho, Administering Sabotage Through Craft courtesy the Artist and Mitchell-Innes and Nash.

Other works scattered throughout the gallery space are two of Ross-Ho’s consistently tidy assemblages in which she stages objects and images against the architectural backdrop of materials like drywall, as well as several of her more concept-craft sculptures, like Bedroom Bandit, and White Goddess #27, both of which juxtapose traditional craft forms with more “classical” art materials, like paint and canvas.

Perhaps the defining work that pulls the show together and – literally – anchors it down is Double Catenary, which consists of two lengths of ½ inch towing chain that hang loosely between the three centered pillars that hold up the gallery walls. The chain, with its glittery goldness that seems simultaneously decorative and utilitarian, playful and threatening, activates the entire space. While the piece doesn’t necessarily point to institutional critique, it is indicative of the thrust of the show, whose organizing principle of spatial and visual non-sequitors is also a careful consideration of site, context, and materiality.

]]>

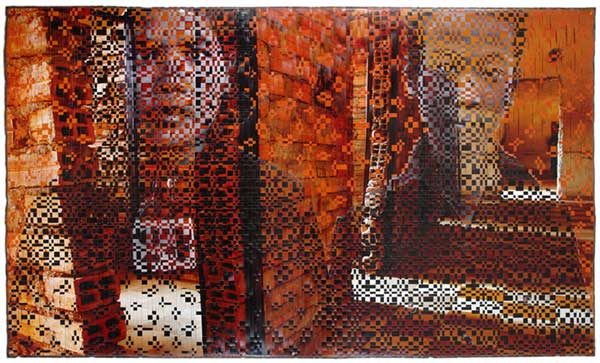

Dinh Q. Lê, Untitled (from The Hill of Poisonous Trees), 2008 via P.P.O.W.

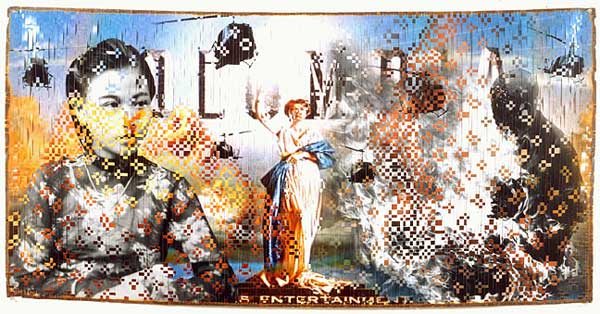

The American war in Vietnam is an inexorable specter that has haunted Dinh Q. Lê’s work since he first emerged as a photographer in the nineties. At the time, he was making what are now considered his trademark works – evocative, large-scale images created by hand-weaving strips of photographs using a traditional Vietnamese grass-weaving technique he learned as a child. The most well-known of these, From Vietnam to Hollywood from 2002, was made from photojournalistic images and film stills from American movies about the war. Lê’s other works in the past decade includes mock, neo-colonial vacation posters criticizing the politics of global tourism during the conflict; and sculptural objects that allude to the brutal legacy of Agent Orange, which continues to cause birth defects throughout Vietnam.

Like most well-behaving spectres, this one wanders aimlessly, feverish with compulsive repetition. Lê’s ghost has no place to call home, and is tenuously tethered only to a global image circuit vis a vis what Andreas Huyssen has called memory cultures. Huyssen writes:

Something else must be at stake, something that produces the desire for the past in the first place and that makes us respond so favorably to the memory markets: that something, I would suggest, is a slow but palpable transformation of temporality in our lives, centrally brought on by the complex intersections of technological change, mass media, and new patterns of consumption, work, and global mobility.

Indeed, in this mediatized, technologized culture of memory, modernist linear narratives are no longer in vogue, and time is most often understood as a place, especially when it comes to histories of war and violence. (I am hearing in my mind Jello Biafra’s gritty ululations in the Dead Kennedys’ prescient “A Holiday in Cambodia” from 1980. The song not only slams white, upper-class leisure, but also ironically suggests how easy it is to ‘go native’ without ever going anywhere.) In this, our present world, the Past is not only a hotter commodity than the Future, but it’s unique brand of malaise and melancholia – based on an implicit suspicion of the future and a familiarity with instability – reigns supreme. This is the space inhabited by Lê’s ghost, now gone totally digital in this most recent exhibition of video and photography.

Dinh Q. Lê, Untitled (Columbia Pictures) 2003 via P.P.O.W.

It is a fitting next step for an artist who has appropriated imagery to create a geography of what Lê calls surreal memory landscapes. These have always had a specific kind of attachment to the actual: the photograph’s indexicality, however disquieting, refers to real physical bodies and real sites of violence as much as it does to spirits of the dead and haunted architectures. For example, Lê’s last solo at P.P.O.W. – in May of 2008 – featured his latest work utilizing his photo-weaving technique, a series called The Hill of Poisonous Trees (a translation of the Khmer “Tuol Sleng”). Here Lê once again returned to Cambodia (he created another series of photo-weaved images photographed in Cambodia in 1998 called Splendour and Darkness), this time using photographs of the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. The museum was formerly Prison 21 (S-21), where at least 200,000 Cambodians were executed during the reign of the Khmer Rouge between 1975-1979. Led by Pol Pot, a French-university trained communist revolutionary, the Khmer Rouge’s rise to power was aided by Nixon’s four-year carpet bombing campaign, a strategic failure intended to bring the conflict to a quick end. In Lê’s images, the raw prison interiors in luminescent golds and reds are spliced together with stark black and white frontal portraits of the accused. In these photographs, one or two faces gaze out from in between the shimmering cracks in the walls, appearing to dissipate into splintered fragments just as they seem to coalesce. In a single glance, bodies and light and walls fuse into one another while disintegrating, a constellation that simultaneously signals order and disorder, obscuration and revelation. From a distance, the images look like fragile, time-worn images, its photo emulsion cracking apart in pieces, falling away. Close-up, the images are all pattern and rhythm and synthesis.

The impact of Lê’s meticulous weaving technique relies on the analog:in the texture and tactility of the photographic papers – not intended for this kind of intense physical manipulation – and the literal piecing together of the imagery two things take place. First, the image takes on a sculptural quality that insists on its presence as an object in space. Second, this presence materializes composite memory, makes death and memory co-habitate, and makes of the photographic object a kind of mnemotechnic. Facilitating anamnesis (literally, the loss of forgetfulness), the photographs perform Socratic work, manifesting the knowledge already inside of us. Lê’s weaved images can be understood as working through the intertextual dimension of memory, making visible its technology. Like composite video, the images take signals – one could say, like luminance and synchronization – and between them, carry information. The images maintain a kind of untenable tension: they are, phantasmagorically, analog pixelations.

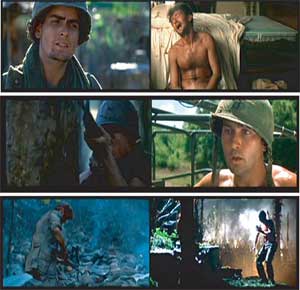

Dinh Q. Lê, Untitled (from the South China Sea Pishkin) , 2009 still via P.P.O.W.

The compositeness of these photo-weaved images is only fully revealed, perhaps, in light of Lê’s newer, fully digital work currently on exhibition at P.P.O.W. The show, entitled Elegies, includes two video installations and several large-scale photographs taken from one of the videos, entitled South China Sea Pishkin. The video is Lê’s first animation, and it turns on the liberation of Saigon on April 30, 1975, which precipitated the infamous and chaotic evacuation of the remaining U.S. presence by helicopter. Hundreds of helicopters fled in panic out to the South China Sea in hopes of landing on U.S. Navy aircraft carriers. An unknown number of them crashed, or were pushed off over-burdened carriers into the sea. The helicopter, that ubiquitous wartime machine with its ominous trademark sound became practically synonymous with Vietnam because of its wide use – and widespread failure – during the conflict. Between 1962 and 1973 alone, almost five-thousand U.S. helicopters fatally crashed, with fully half of these due to mechanical failures.

In Lê’s meticulously clean, hyper-real animation, rough waters lie in wait to claim metal wreckage as helicopter after helicopter falls into the sea. The helicopters are without pilots; some hover, struggling desperately to maintain above the waters before finally giving in; some seem like lifeless masses thrown violently from a merciless sky, while still others dive into the waters with a suicidal mania. In a spectacular, never ending display, the U.S. war machine, once symbolizing American might and technical prowess, fails over and over and over again.

Dinh Q. Lê, From Father to Son: A Rite of Passage 2009, via P.P.O.W.

The other video in the exhibition, called From Father to Son: A Rite of Passage, is a two-channel video that re-edits scenes from two iconic Hollywood films about Vietnam, Coppola’s Apocalypse Now from 1979 and Oliver Stone’s Platoon from 1986. The video sets in parallel scenes of Martin Sheen in Apocalypse with scenes of Sheen’s real life son, Charlie, in Platoon. In Lê’s narrative re-working, the two soldiers experience ‘the horror’ of war simultaneously, as if present in the same drama: son witnesses father having a post-traumatic breakdown; son, in turn, has a freak out all his own. Both father and son, portraying young American soliders, must kill an older American solider gone bad. It is a mirroring of the particularly American brand of the patriarchal cycle of violence (what Viet Nguyen has called – writing about Lê’s work – “Americas great cinema industrial complex.”). It suggests not simply that violence is learned through our fathers, but also, in a Freudian turn, that we must kill our fathers in the process of learning. It’s an Oedipal moment too, positing that the mother nation / mother Capitalism has cast a spell on us all. Even further, the two scenes do the tricky work of redemption; each attempting to restore the fallen American heroism as the bad, evil or misguided masculinity is purged, literally, through a performance of a less tainted, ‘good’ violence.

The power of this work lies in Lê’s use of the digitized image – a move that transforms the quandary of composite memory into a one of saturated memory. In South China Sea Pushkin, the more than life-like rendering of the sea and helicopter, once symbols brimming with meaning, are almost too full. In From Father to Son, the cinematic text is overlain with a personal one, an endless mirroring across historical, cultural, and personal memory. In both cases each textual understanding of the image is stored with the knowledge of the one before (each progressive video scan subsuming the next), unfolding a mnemonic space within each. It is the memory spaces between the texts that Lê is now interrogating. Like the wreckage of helicopter machinery heaped on the ocean floor, growing like Benjamin’s pile of debris towards the sky, the accumulating cultural data – about war, about the human capacity for violence – is a kind of speculative potential. Lê’s tapestry of memory, once fragile, is now a binary algorithm, powerfully and infinitely transformable. The ghosts of wars past still haunt Lê’s work – only now, they are likely to go viral.

]]>

Haiti's Presidential Palace, post-quake via boston.com

In the aftermath of the devastating earthquake that hit Haiti’s capital, Port-Au-Prince, on January 12th, the magnitude of human suffering and loss overwhelms. It is a feeling compounded by the legacy of colonial exploitation and postcolonial mendacity – the grim chain of human-induced events that tumble recklessly, one after another, exacerbating the current disaster. In the wake of such catastrophe it is important to understand our place in it – and consider it from a variety of angles. What, for example, is the role of culture, and how do we talk about it?

Last week both the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times featured headline stories about the impact of the earthquake on Haiti’s national treasures: the National Palace, the Notre Dame Cathedral, and the Episcopal Church’s Holy Trinity Cathedral, and collections at the Centre d’Art, Haiti’s main art museum, the Musee D’Art Nader, and at private homes. Assessing the damage to buildings and artworks, the two news articles read the power of culture as a symbol of strength; culture as evidence of beauty in the face of poverty and tragedy. Both stories isolate culture as a kind of naïve, hermetic beacon, at once inspiring, yet removed from historical and political context and devoid of complexity. The narratives cling to a narrowly understood narrative of heritage that eclipses responsibility and a wider view of the economic entangled with colonial history. Further, the articles’ sympathetic tones hover between condescension and romanticization, making a nostalgic object out of their poverty, their struggle for independence from slavery, and their cultural losses.

In his article, the New York Times’ Marc Lacey writes,

Long before its ground started heaving, Haiti was already a byword for a broken place. Its leaders were considered kleptocrats; its people were jaw-droppingly poor. But there was still a pride that burst forth from the people here, linked both to the country’s heroic history and to the vibrant culture that united them and enabled them to endure… in stealing symbols that gave Haitians their hope and grandeur and reminders of a common purpose, the earthquake cast a different kind of shadow over their future.

It’s a typical first world story of the poor, quaint, third world: all they have is their heritage. The missing context? Culture is what remains after colonialism plundered their resources, neocolonialism interfered with their politics, and neoliberalism made them economically dependent. Certainly Haiti’s own corrupt leaders have played no small role, but the lack of gesture towards the complexity of history contributes to a concept of both history and culture as pure, redemptive, and singularly edifying.

Notice also the way in which poverty is made a spectacle (“jaw-droppingly poor”) and the personification of the earthquake disaster as a faceless, uncivilized monster who takes without reason. In so doing, Lacey evokes an image of savagery not unlike the historical colonial narratives about the Caribbean that would, one hopes, would today make us cringe. Haiti and her culture are always already in the past (a la Fabian) – the “future” that Lacey suggests is one that the reader knows is always behind us. This temporal restructuring is hegemonic, isolating the Other in another time that is another place (The Past), even when the chronological time is the present.

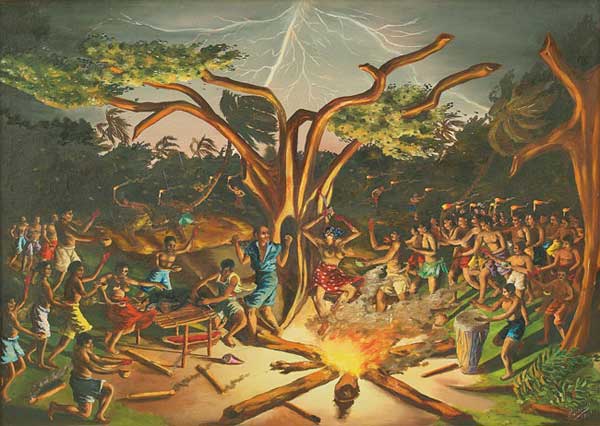

Louverture Poisson, Vodoo Ceremony, c. 1954; via treadwaygallery.com

To be sure, cultural objects, and the discourse surrounding them, have consistently served as pawns in our civilization’s long, ugly history of war and violence. Consider the collections of artifacts and antiquities housed in major historical museums across the Western world. These collections can be seen as a record of imperialist desire and the power to take (though often in the name of science and preservation). A weapon of nation-building, art objects are inextricably bound up with a kind of global ordering. They allow nations to claim history and shape it, to locate themselves via friend and foe alike.

Recall the looting of the Iraq National Museum. In the chaos of the American-led invasion of Baghdad in April of 2003, thousands of ancient artifacts and artworks were stolen from the unguarded institution. Despite an international demand to protect Iraq’s historical sites and buildings, the U.S. military showed little interest in preserving Iraq’s cultural history. Recall, also, the toppling of the 20-foot tall statue of Saddam Hussein in Firdus Square by a U.S. Marine Corps armored recovery vehicle in front of the international press. In this highly choreographed event, the U.S. made strategic use of certain, indigenous Iraqi symbols. This performance is in stark contrast to the manifest indifference displayed following the days of the museum’s looting, when U.S. soldiers stood by as pillagers ran amok with armfuls of antiquities, even as museum curators and conservators pleaded to them for help. This loss was devastating, a kind of irreversible destruction that mortar shells and smart bombs could never inflict.

Contrary to the U.S. history of disrespect towards Iraqi cultural history, the Los Angeles Times’ story reports that UNESCO, in collaboration with local arts collectors and historians, has located protection for its historical and cultural objects in advance of any potential looting in Haiti. Breathing a sigh of relief that for once, the U.S. and its allies at the U.N. can represent itself as a force of humanitarian goodness rather than a force of political violence, the international community paints themselves as noble saviors.

photo: Michael Appleton via the New York Times

But similar to news stories that reported the pillaging of the Iraq Museum is the Times’ characterization of Haiti’s loss: “With dozens of galleries, museums and other venues badly damaged in the quake, Haiti’s arts community is sick at heart.” Represented as a kind of illness, the loss of art weakens the body of a skeletal nation. One can imagine that the destruction of the MoMA might merely rip a hole in America’s trouser pockets. But in the case of Haiti, such destruction is understood as illness because it attacks what is most vulnerable. Again we see the implication of a quaint, childlike weakness as representative of an entire people.

Civilizations cling to cultural objects, imbue them with history, and regard them as reflections of our collective consciousnesses. Culture remains a struggle over meaning and memory; one that enlarges an understanding of ourselves and our place in the world, on both individual and community levels. Global capital notwithstanding, a nation’s value resides in the history of its objects, in the history of how it has represented itself over time.

There can be no doubt that Haiti’s losses are deep, and the artists and arts community are suffering in ways that have not been adequately represented. In the midst of staggering death, there is sorrow over destroyed paintings, murals, sculptures, and old books: irreparable, irretrievable. The loss of these works is all their own, because it is their past, their history, their own present. As one Haitian artist interviewed by the New York Times, Patrick Vilaire, states plaintively, “The dead are dead, we know that. But if you don’t have the memory of the past, the rest of us can’t continue living.”

]]>

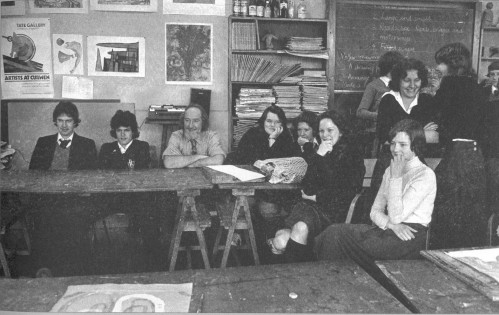

Darcy Lange, Study of Three Birmingham Schools, 1976 via Adam Art

Recall the last time you spent three hours in one gallery engaging with a single artist’s work. Darcy Lange’s (1946-2005) exhibition about methods of teaching and learning at Cabinet demands as much, if not more. Consisting simply of three television monitors with headphones on a sawhorse table and a short row of mounted black and white photographs hung on two walls, Darcy Lange: Work Studies in Schools functions more like a library than an exhibit. And as such, it is a much-needed ruler rap across the knuckles, requiring us to slow down, stay awhile, and ponder some older but still sharply resonant questions about education.

A New Zealander who studied at the Royal College of Art in London during the early part of his career, Lange began his ambitious Work Studies video documentary project with the intention of examining the British education system in relation to the production of class identity. Lange’s Gramscian sensibility reveals school as a social class incubator, a hothouse for breeding ‘common sense’ knowledge that naturalizes culture and morality. Concerned with education as a hegemonic institution, Lange’s primary task is to offer a vision of youth being molded into the social order, to document their processes of learning to labor. At a time when no institution plays a larger role in bringing America’s youth into the dominant regime than public schools, and battles over education reform, and public funding for education continue to rage, Lange’s project raises probing and relevant questions about the essentially political process of education.

Darcy Lange, Studies of Teaching in Four Oxfordshire Schools, 1977 via Adam Art

Lange videotaped in classrooms at three different schools in Birmingham in 1976 and four schools in Oxfordshire the following year. He included both public and private schools, aiming to represent a spectrum of class experiences. His methodology was strict: Lange would videotape a lesson, replay it both to the students and to the teacher afterwards, then interview both teacher and students about their responses to the remediated lesson. During one class I sympathized with the dreamy young chap staring off in the distance and the wide-eyed girl gnawing intently on her fingernails while the teacher, in dramatic tones, waxed on about the origins of the wheel. The teacher later regrets his long-winded lecture, saying he failed to interact with the students and inundated them with too much material at once. At St. Mary’s private school, a proper Mrs. Webb powerfully engages her history class full of teenage girls – all white – in a juicy discussion of King Henry VI’s marriage. In her follow up interview, I watched Mrs. Webb stress the importance of teaching politics to kids from wealthy backgrounds in order that they might have “a broader view of contemporary society,” and be “less prejudiced later in life.” Recalling her easy classroom banter about the authority of the English crown, it seemed as if they were gossiping about people in their own neighborhood. And while there is no discernible difference in teaching methods between public and private schools, between teaching working class kids versus middle or upper class kids (these differences made legible largely through the racial make up of the classroom), what is laid bare are the implicit markers of class hierarchy within certain kinds of knowledges.

Recording in single, long, real time takes, without any cuts or the dramatic use of camera angles, Lange uses the slow observation techniques familiar to visual anthropology, and the non-illusionist, structuralist approach to filmmaking. This situates his project somewhere between Warhol and Flaherty, flavored with a bit of New Deal sentimentality. The videos are shot in varying degrees of fuzzy and dull black and white, and the camera rarely gives the viewer an establishing shot (a critique one of the students makes). Instead, the camera roams, slowly moving in to capture students’ faces as they self-consciously stare back at the lens, revealing the ideological position of the camera, while also reminding us that they know it is there.

Darcy Lange, Work Studies in Schools, 1977 via mirjamvantilburg

With more than twenty-three DVDs available for viewing upon request (many of them over an hour long), sitting and watching disc after disc was not unlike doing research. Ostensibly the videos could be used as pedagogical tools to improve teaching methods, and indeed, Lange had hoped for their formal use outside of galleries and museums. There are many cringe-worthy moments that recall vividly Bourdieu’s notion that class distinction is embodied chiefly in schools–as when primary school teacher Mr. Hughes reflects on the role of the teacher to instill social mores and values that are “in the best possible interest for the children,” or when Mrs. Webb states that teachers are “limited by their exam subjects.” These force us to consider the precarious position of schools and education in shaping culture. By engaging his subjects and the audience in a reflective video-making process that is constitutive of the work itself, Lange, following Gramsci, reveals the political questions bound up with the cultural ones embedded within both art and education. But the real power of the work is its eerie foreshadowing of the neoliberal approach to education – commodification and standardization – while also challenging the utopian concept of education as a public good that will magically erase class differences. The conundrum that remains (à la Bourdieu) is an uncomfortable tango between cultural capital and a hierarchical educational system that inevitably reproduces social classes – a quandary that should demand the attention of artists and educators alike.

]]>

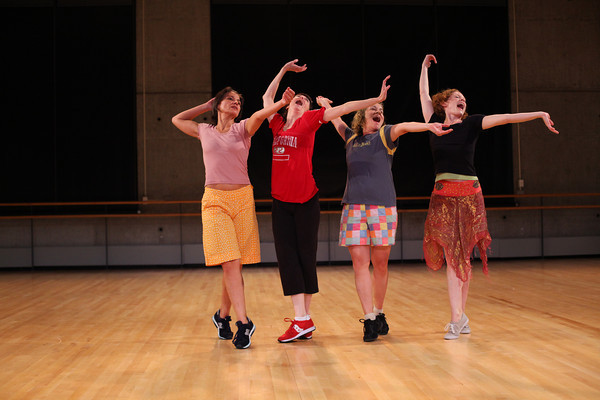

Yvonne Rainer, Spiraling Down, 2009. Performers, left to right - Pat Catterson, Patricia Hoffbauer, Sally Silver, and Emily Coates. Photo: Paula Court, via Performa.

While performance is a term that has been grappled with at least since Aristotle, our particular age seems obsessed with ‘performativity’ or the ‘performative,’ concepts that have become almost ubiquitous across multiple discourses. These terms are useful precisely because of their interdisciplinarity: they speak evocatively to intersecting issues like gender, language, and repetition. But they are also slippery terms that we happily overuse – a seductive calling for the return to live performance – and perhaps lived experience – itself. PERFORMA seems to be the quintessential example of this giddy indulgence.

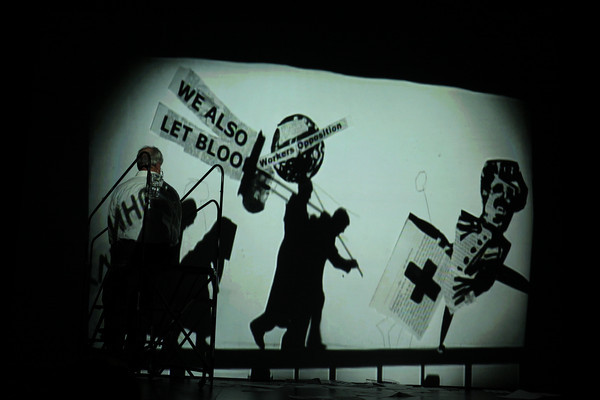

We are thrilled to have such a relentlessly frenetic and delirious display of performance-related events thrown at us, and there’s a vital risk-taking in much of what we have experienced. If you are a contemporary artist who doesn’t dabble in performance, or the performative, or performativity (see, there it goes a-slipping), it seems that, well, you’re not very contemporary. Everyone from Wangechi Mutu to William Kentridge played their part in the festivities this year, all to much interest but with varying degrees of success. Now that the final curtain on PERFORMA has been lowered, and the visceral excitement has burned off, we are left with vague feelings of disappointment. In the cooling embers of what remains, Why performance? is the question that arises.

William Kentridge, I Am Not Me, the Horse is Not Mine, 2009. Photo: Paula Court, via Performa.

I wonder at this need for immediate encounters between the body and the event and the seeming, sudden relevancy of live performance. I suspect it has something to do with the widespread degradation of experience enacted by a surfeit of images, insufficient against ongoing war and economic crises. I recall the numerous PERFORMA events I have attended over the last few weeks, and struggle to regain the memory of these experiences. Some have grabbed hold, while others have receded, but in all cases some trace of being there remains. Performance, after all, is about the presence of the body, and not just the performers’ bodies, but also our own.

Often, when performance doesn’t succeed, it is due to a failure of the artist to fully consider the relationship between the body, its representation, and its relationship to the audience. Performance is riddled with problems around power and authority, and when that power is unquestioned, normative modes of performer/spectator relations reign, passivity overcomes us, and the time of event (our conscious presence in that moment) is lost. How we feel, and read the body is the essence of our encounter. These responses determine our ability to transcend the specific actions on stage and inhabit a time constitutive of the event’s fullness, a practice of “being in the event.”

Deborah Hay, If I Sing to You, 2009. Performers left to right - Michelle Boule, Catherine Legrand, Ros Warby, Jeanine Durning. Photo: Paula Court, via Performa

Yvonne Rainer and Deborah Hay’s recent double-billed performance at the Baryshnikov Arts Center, as part of PERFORMA 09, provided an intensive reminder of this practice. That it should be these two that did so is no surprise. Legendary figures in the postmodern dance movement and founding members of the Judson Dance Theater, an informal group of dancers who performed at the Judson Memorial Church in New York between 1962 and 1964, Rainer and Hay came out of a period of intense experimentation. They rejected modern dance composition and championed everyday body movements. Both choreographers challenged the traditionally narcissistic and voyeuristic structure of dance by shattering the privileged position of the virtuosic dancer. Instead, postmodern dance put anybody and everybody on stage, forging a new relationship between performer and spectator, and denying the performance as spectacle.

Heavy traces of these avant-garde dance elements can be found in Rainer and Hay’s latest works at PERFORMA, two dances that reveal their shared intellectual heritage but also re-activates the body as central to performance.

Deborah Hay, If I Sing to You, 2009. Performers left to right - Alana Elmer, Amelia Reeber, Jeanine Durning, Michele Boule, Catherine Legrand, and Ros Warby. Photo: Paula Court, via Performa

Hay’s If I Sing to You begins with its five women performers standing awkwardly pressed together and softly but nervously humming or chattering to themselves. Some of the performers sport patchy facial hair appliqué, confusing gender altogether. The next hour finds the women engaged in entrancing activities like wrestling, scampering around on tiptoe, wildly embracing each other, barking, humping on the floor, shaking, and crawling. At times, the dancers seem utterly alone, and at other times, inescapably together. Always absurd, their bodily transactions are fiendish and giddy, sexual and child-like, vulgar and simple, an unfettered release that is both confounding and exhilarating.

Hay’s choreography depends heavily on her individual dancers, and the five performers (Michelle Boulé, Jeanine Durning, Catherine Legrand, Amelia Reeber, and Ros Warby) deliver. Their adroit bodies – most notably Boulé’s strangely magical naïveté – opened up an uncanny space between experience and consciousness. It was a raw, uncomfortable familiarity, too mesmerizing to let go, and, given the intimate space of the Center, it forced a tense physical and psychical proximity that prevented us from forgetting our own presence.

The dancers’ queer movements and nonsensical gibberish, all dictated by a sense of jouissance, reflect the unintelligible, undisciplined body hovering dangerously at the edge of pre-linguistic consciousness. Clearly transacting emotions within themselves, to each other, and to us, If I Sing to You is about the body coming into language, and all the gender disciplining (bodily or otherwise) that goes along with it. And through our kinetic familiarity with the performers’ everyday actions, the performer / spectator binary is recast, our subjectivities splayed out as raw as the bodies thrusting in front of us.

Language and the body are equally important to the always-playful Rainer. In her New York premiere of Spiraling Down, Rainer finds her bodily language in an mélange of historical and contemporary sources, such as old movies, the comedic movements of Steve Martin and Sarah Bernhardt, ballroom dance, and in sports like fencing and soccer. Her repurposed texts come from newspapers and novels, including Haruku Murakami.

Deborah Hay, If I Sing to You, 2009. Performer, foreground - Catherine Legrand. Photo: Paula Court, via Performa.

Spiraling Down begins with Rainer speaking Murakami’s words in a disembodied narrative that equates the seemingly dissimilar activities of writing with running. Murakami’s text frames the dance (and perhaps all of what dance and performance could be) as an intellectual exercise, one that makes connections between the body and the brain, calling attention to the textual capacities of the body. The body, as performed by Rainer, is not simply something that can carry content (choreographed movement or otherwise), but is also dense with meaning (social or otherwise).

Like Hay’s cast of performers, Rainer’s unofficial, multi-generational dance troupe, which includes Pat Catterson, Emily Coates, Patricia Hoffbauer, and Sally Silvers, consists of all women. And while they are all clearly women, they seem gendered otherwise somehow, rendered strange through their unfamiliar presence on stage set against their everyday appearance. The dancers’ variously aged bodies, lacking the pretension of virtuosity, force us to recognize the mediated aspects of performance.

The dance ruminates on different subjects, from war and technology to impotence and soccer. It’s a pastiche of movement and language that jumps haphazardly between texts both physical and linguistic, producing a stage time that is neither linear nor narrative. This melancholic fragmentation calls attention to each dancer’s bodily relationship to the time of the event itself and to temporality more broadly, creating a kind of embodied ‘present’ that is difficult to escape.

There are elements of chance and improvisation implicit to the structure of both Hay and Rainer’s choreography that create a palpable tension and anticipation. Hay allows each dancer to choose her costume, which determines her gender, right before each performance, which then affects both the staging and the solo elements. Rainer choreographed set movements, which the dancers can choose to perform according to their own timing.

Yvonne Rainer, Spiraling Down, 2009. Performers, left to right - Patricia Hoffbauer, Pat Catterson, Sally Silver, and Emily Coates. Photo: Paula Court, via Performa.

Through the vocabulary of postmodern dance drawing on pedestrian movements, fragmentation, and juxtaposition, Hay and Rainer remind us of the mutability of the body and the self. We witness the body’s domestication and struggle against the memory of our own. And if we understand dance, as event, already in the process of becoming a memory, Hay and Rainer make us painfully aware of our fragile relationship to time. Unlike the slapped-together sloppiness of much that gets peddled under the name of performance, events such as Hay and Rainer’s dances prompt us to recognize that performance has form, structure, history, and, well, an audience. In now recalling their dance performances, which happened less than two weeks ago, my memory of it exceeds the event, seeping into embodiment and my physical sense of being there.

Perhaps PERFORMA’s current relevancy and our recent energetic turn to performance is connected to the valorization of the 60s and 70s in the history of contemporary art. It is worth recalling that those radical shifts in performance and dance took place at a similar moment of national aggression, then in Southeast Asia. Consider also the continued resonance of The Society of the Spectacle, published by Guy Debord in 1968, whose depiction of a certain modernity, drained of all directly lived experience, has yet to be supplanted. Indeed, amidst our current moment of war and economic upheaval, our desire to remember, and to engage with each other at levels beyond the limits of the spectacle seems all the more understandable.

Performance – with its implicit continuity and unique temporality – bears an unavoidable relationship to the present. In the packed crowds at PERFORMA, as bodies heated up against bodes in many spaces, this alliance can be felt. Unlike Chelsea openings that feel more like awful holiday store crowds, live performance gives us the feeling that we are part of something. We feel the transaction between the performer and ourselves, and, when it is good, it pricks us, a kind of punctum that reminds us that we are here. Even if the sharing of space, of consciousness, is not altogether genuine, it can at least gesture towards the fantastic possibility that our memory will not fail us.

]]>