Via Museum of London

Greetings Readers!

There are several exciting developments at IDIOM.

First, we are emeritus-ing our faithful and fearless books editor, Jessica Loudis, who has taken a position as Assistant Editor at Bookforum. Loudis has been a stalwart ally and rare friend, and we wish her the very best at her fancy new digs.

Second, we have three new editors to introduce!

Alyssa Reeder (Arts) was born and raised in California. She moved east to attend The New School of Liberal Arts, and is now a contributing writer and editor for The New York Times, Whoa Magazine and other publications in New York City.

Morten Høi Jensen (Books) was born in Copenhagen, Denmark. He is a freelance book critic and translator, and has written for Bookforum, The Quarterly Conversation and Open Letters Monthly. He is a founding editor of UgarteMagazine.

Tom McCormack (Film and Electronic Art) is a critic living in Brooklyn. His work has appeared in Cinema Scope, Film Comment, Moving Image Source, Rhizome, The L Magazine, and other publications. He is also an editor at Alt Screen.

We are thrilled to have these three wildly talented editors on board, and can’t wait to introduce you to them in person.

Also be sure to read the IDIOM essays reprinted in the summer issue of the Jacobin, available at discerning newsstands and online.

Lastly, IDIOM will be on semi-hiatus through the month of August. We will be re-running some essays previously published, along with new material, and will resume producing all-new words come September. In the meantime, please plan on joining us for a party in mid-August.

Thanks so much for reading. And we hope to see you soon.

Stephen Squibb, Barry Hoggard, and James Wagner for IDIOM

]]>

Adolph Ziegler, The Four Elements: Fire, Water and Earth, Air, before 1937. Via arthistory.about.com.

Kenneth E. Silver’s Chaos and Classicism: Art in France, Italy, and Germany 1918–1936, closing presently at the Guggenheim, has been justly celebrated as a timely, fascinating and refreshingly serious exhibition. An audacious presentation of largely marginal works, the show banks instead on the historical and intellectual appeal of its theme: the return of classicism in the interwar art of Italy, France and Germany. The show’s immediate success, palpable almost upon arrival, speaks not only to the diligence and command of its curators, but to a deeply felt resonance between its moment and our own. What makes Chaos of lasting interest, however, is precisely the extent to which it disrupts this easy parallel: it is difficult to walk away from this exhibition with one’s ‘we are Weimar’ fatalism fully intact. Illuminated instead are the differences between our homegrown forms of Rightist reaction – at least at the level of art and culture – and those of Italian and German fascism. Put simply, it is hard to imagine any of our contemporary demagogues having any paintings at all above their mantle, even ones as kitschy and ridiculous as Adolf Ziegler’s Four Elements: Fire, Water and Earth, Air, which enjoyed pride of place in Hitler’s Munich apartment and performs as the tawdry climax of Chaos. Perhaps Sean Hannity just loves Thomas Kinkade, but I doubt it.

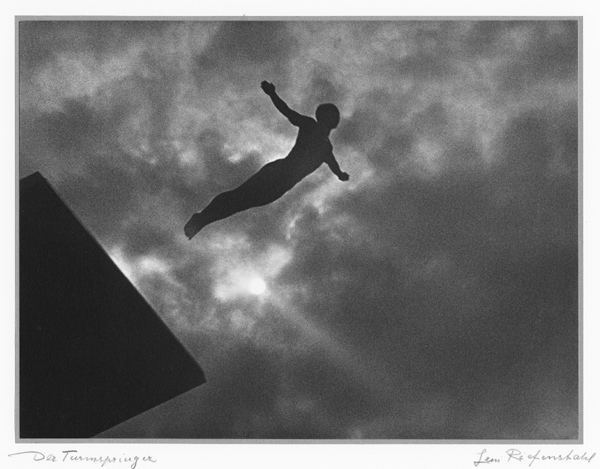

Leni Riefenstahl, Olympia, 1938. Via purestorm.

The story being told is familiar at the level of sociology but is often eclipsed art-historically by our fascination with the avant-gardes, whose provocations never penetrated the popular imagination to the extent of the work shown here. Europe, deeply disturbed by the savagery of the First World War, sought refuge in classical forms whose very appeal belied their distance from industrial civilization. The lingering trauma of The Great War was sublimated into a desire for the purity, order and clean lines of antiquity. That these forms were always ideological – there was nothing particularly pure, clean or orderly about Rome or Athens at the level of lived experience – accounts, bizarrely, for their allure. Indeed, what is so striking about the interwar classicist revival is just how consciously it was pursued – a fact elegantly detailed in Silver’s catalog essay, “A More Durable Self.” It was precisely the anti-realism of classicism, when realism would have meant a lifetime of images like those of Otto Dix, which made it so broadly seductive. And here the architecture of the Guggenheim really is put to spectacular use. We are literally lifted us away from Dix’s etchings, here located on the ground floor, and into the airy realm of ideal types, rehearsing the flight of the history on display.

As we progress up the spiral towards the inevitable, symbolized not only by the aforementioned Ziegler but also by Leni Riefenstahl’s show-stopping Olympia, what stands out is the clarity of the opposition between Right and Left cultural positioning. Unlike today, that is, where sexism, racism and homophobia are re-branded as one side in a ‘culture war’ for which they have neglected to show up as art, in interwar Europe there actually was a contest between two competing accounts of what painting and sculpture can and should be. Fascists, whose terrible taste is on such ample display as to achieve a kind of grim hilarity, still felt that art was worth fighting for. Today’s Right just wants it to go away.

Adolofo Wildt, Portrait of Benito Mussolini, ca. 1925. Via artnet.

It will perhaps be objected that the Tea Party’s open pining for the days of lynching, indentured sexual servitude and the twelve hour work-day amounts to a kind of crypto-classicism, because nostalgic, aggressive and unmoored. But this is to miss the central, negative insight made available by Silver’s work, which was touched on in an online forum. Here Julian Stallabrass made reference to Perry Anderson’s linking of classicism to an aristocratic legacy, which Martha Rosler then furthered by citing the criminally under-appreciated Andreas Huyssen. Huyssen makes clear that neither modernism, American or European, can be properly understood without reference to the distinctions between those continents’ respective social histories. Without the canonization of Euro-modernism, the American modernist moment would never have been ‘post-‘ in any meaningful sense. Similarly, without an aristocratic heritage of our own, the categories of European political history – and the contours of their aesthetic ideologies – cannot be imported wholesale. And this, finally, is what makes Chaos and Classicism so valuable: by presenting the reality of the fascist shift in European art, the Guggenheim stymies the central positioning of that moment within the American political imaginary. We may be headed towards disaster, if we are not there already, but this tragedy, when it arrives, will be a farce of a different color.

]]>

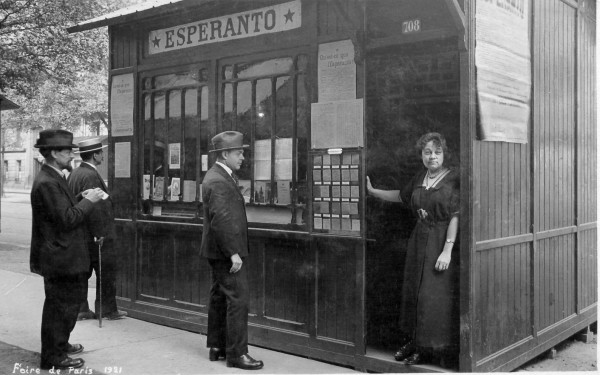

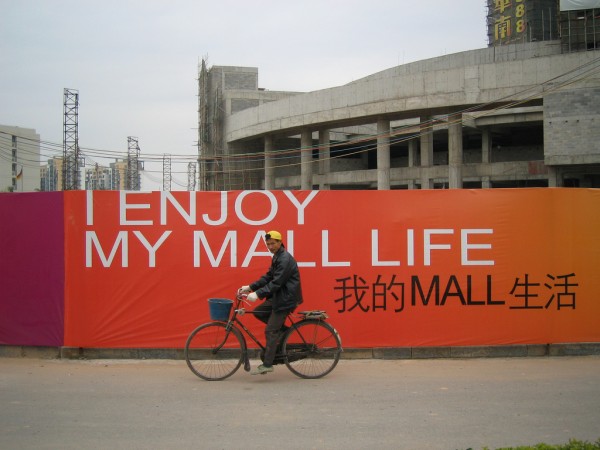

Sam Green, Utopia in Four Movements, 2010. Via Washington City Paper

Given the many victories won by progressive movements in the modern era, it is worth asking after the pervasive narrative of failure that surrounds their legacy. Even exempting the entirely predictable, institutional reaction personified by certain pink-faced half-wits, many people remain locked in a deep and abiding pessimism. By what standard can a tradition so accomplished be found so wanting?

The answer is provided by Sam Green in the title of his engaging live documentary Utopia in Four Movements, which played the Kitchen last week. Green, who admits to approaching the term ‘utopia’ with equal parts affection and cynicism, has created a striking mediation on four examples of what he takes to be the utopian impulse. The extent to which each of these is, strictly speaking, utopian is debatable; a fact acknowledged by the filmmaker when he admits that, for him, utopia is as much about hope and imagination as creating heaven on earth. The admission is indicative, but what might have been a fatal confusion becomes – in the dexterous hands of Green and his collaborators, musicians Dave Cerf and the Brooklyn-based Quavers, an animating, even appropriate, tension.

Indeed, the most consistently satisfying aspect of Utopia is the contrast between the novelty of its form and the consternation of its content. Mixed from live voice over, film and images (Green), recorded sound (Cerf) and live music (the Quavers), the format combines the nerdy pleasures of documentary with the emotional heft of live performance. Thus while Green is detailing the grim fate of this or that ideal, experiment or movement, we are being serenaded with the building uplift of the Quaver’s prog-rock. This friction could probably be pushed even further, as the more the different elements pull in conflicting directions, the more complicated, and interesting, the presentation becomes.

Sam Green, Utopia in Four Movements, 2010. Via UIFM

After an introduction, we begin with Esperanto, the fully synthetic language created by one polish Doctor Zamenhof in 1887. Zamenhof believed that linguistic pluralism was a primary cause of the inter-ethnic enmity he experienced during his childhood:

The place where I was born and spent my childhood gave direction to all my future struggles. In Bialystok the inhabitants were divided into four distinct elements: Russians, Poles, Germans and Jews; each of these spoke their own language and looked on all the others as enemies. In such a town a sensitive nature feels more acutely than elsewhere the misery caused by language division and sees at every step that the diversity of languages is the first, or at least the most influential, basis for the separation of the human family into groups of enemies.

Green deftly sketches the history of the movement, wisely spending most of his time on footage of contemporary Esperanto speakers gathered at annual conferences. Interspersed with some of the more outlandish episodes in the language’s history- the all-Esperanto William Shatner film is a highlight – Green finds a strikingly cosmopolitan community whose common faith goes some distance in justifying the idealism of its founder. While Green’s voiceover emphasizes a personal wariness towards the idea of a universal language, his camera seems less concerned, even celebratory. The segment climaxes with a beautiful, on-camera performance of a song, in Esperanto, detailing the daily tragedies of life around the world. The images pretty much speak for themselves, but Green’s voiceover intrudes, narrating his implicit inner conflict as he confesses that he simply couldn’t get the tune out of his mind. It’s becomes a routine conceit: the filmmaker doing our hedging for us, and its alternately endearing and frustrating as the performance wears on.

‘The Revolution,’ comes next, and, after a brief treatment of twentieth century socialism – which does note, however cursorily, the distinction between utopian and scientific socialism so central to that tradition – we arrive in present-day Cuba, where a member of the Black Liberation Army has been living in exile for twenty years. This activist, set against advertising-free – if propaganda-laden – Cuban landscape provides further opportunity for Green’s brand of heavily qualified appreciation. And it was here, more than at any other point, that Utopia felt most explicitly designed for an American audience rather than a New York one. Positively elegiac, Green wonders if something won’t be lost when capitalism inevitably triumphs in Cuba, filling up all that public space with garish ads for KFC. As ever, the cinematography is superb, and simply seeing Cubans going about their daily lives feels more subversive than it probably should.

Sam Green, Utopia in Four Movements, 2010. Via UIFM

The third and strongest section deals with the construction, in China, of the world’s largest shopping mall. Unearthing the socialist background of an early shopping center pioneer, Victor Gruen, Green gives us a fascinating portrait of the slow death of an ideal. One by one, the day-care centers and community gardens are shorn from Gruen’s plans by developers, until, late in life, he is finally forced to denounce his creation as a totally degraded form of his initial intention. In China meanwhile, the billionaire behind the latest, largest mall has chosen a location that’s entirely too remote, on the hope of drawing patrons post-construction. When these customers fail to materialize, the Party maintains operation of the mall’s many amenities by subsidy, so as to avoid losing face. The resulting landscape, all vacant stores and empty rollercoasters, is sort of a documentarian’s wet dream, and Green takes full advantage. Gently constellating this colossal fuckup with interviews of various employees and shots of mascots gamely performing to evacuated parking lots, Green finds a bittersweet humor as the contradictions bubble to the surface. This vast, hollow temple of consumption – built by a billionaire but maintained by the state – captures beautifully China’s conflicting utopian legacies, equal parts communist and capitalist. It is also the only moment where Green seems willing to consider that utopianism might not be an exclusively leftist disease, but more on this later.

The last movement, entitled ‘Elegy for the 20th Century,’ focuses on the work of forensic anthropologists trying to identify bodies in mass graves. Intended as a sort of counterintuitive moment of optimism, it seems instead to double down on some of the earlier interpretive questions surrounding this term ‘utopia.’ I mean, if wanting to know where your murdered child is buried is utopian, then things are even worse than we thought.

And that, ultimately, is the best and the worst thing about these Four Movements: the decidedly pregnant misunderstanding at their center. So let’s be clear: very little of what Green considers to be ‘utopian,’ actually is, and often it’s not even close. Utopia, as we’re reminded early in the show, is a no-place, an impossibility, and to call something ‘utopian, like calling it ‘ideological’ is typically derogatory and reserved the position of one’s opponents. There is a difference, in other words, between saying that everyone should have enough to eat, and that everyone should be able to eat whatever they want, whenever they want, and also never be unhappy or in pain, plus pets and cake. The former is a possibility that has existed for decades, the latter is utopian. And watching Green, a very smart and charismatic figure, routinely describe the ambitious, the unlikely, or even, most surprisingly, simply the good or the correct, as ‘utopian’ is finally quite disturbing. This effect is magnified when the virulent market utopianism of the ongoing neo-liberal nightmare is mentioned only in passing; the impact of the American embargo against Cuba is downplayed; and Marx – he of the international campaign for the eight-hour workday – is said to have believed himself in possession of some magic utopian formula. The point is not that Green is a right-wing ideologue; on the contrary. What is fascinating is that this investigation of utopia, elegant and commendable in every aesthetic respect, has so completely internalized a reactionary semantic framework – to the point of ignoring utopianism where it exists and finding its where it doesn’t.

But Green is not writing an essay, he’s doing performance and by dwelling on the surface of the work we risk missing the deeper questions it would ask. It would be one thing, that is, if this fraught sort of relationship with the past was an isolated phenomenon, but it isn’t, far from it, in fact. Thus what Green is performing so clearly, (and let’s leave out the murderously dull and tragically prevalent fixation on intention here; they’re all primary sources at the end of the day), is his generation’s characteristic substitution of fascination for commitment. Rather than picking a side we seem endlessly content to study, with a level of detail bordering on the obsessive, those ideals and positions that we ought, by cultural and historical rights, to be openly partisan for.

Sam Green, The Weather Underground, 2003. Via arttattler

This trend was equally evident in Green’s previous film, The Weather Underground, also excellent, which consumed itself with documenting the fallout from radical commitment. Here was Todd Gitlin, still mad at Weather for breaking up SDS. Here was Mark Rudd, full of remorse and confusion. Here was Bernie Dohrn and Billy Ayers, grim faced and stoic. And then, in the middle, in a series of blink-and-you-missed-it cameos, was an FBI agent assigned to their case, cheerfully admitting to harassment, intimidation and torture, “I know some people of the liberal persuasion might have a problem with it,” he laughs, “but hey, if you’ve done nothing wrong you have nothing to worry about.” A moment later and we’re back with Rudd looking wistfully out to sea, or with Brian Flanagan walking down 11th street or whatever. The fact that the Bureau broke so many laws in pursuing Weather that they couldn’t even be prosecuted is mentioned, but not dwelt upon because- and here’s the key- the debased ruthlessness of the alternative isn’t as mesmerizing as those whose mistakes we must never risk making.

Now, this is one thing when dealing with the categorically ridiculous Weatherman (The lyric is: “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.” That’s don’t. As in: Do Not Need. Forty years later, the stupidity remains breathtaking.) and another when offering a survey, however incomplete, of the progressive impulse writ large. This is why, though Weather is the formally superior work, Utopia is much more significant, because Green’s voiceover foregrounds this neurotic cycle of critical fascination and distancing. Listening to him explain these four movements, we are placed, productively, I think, in the role of socio-cultural analyst as the misapplication of ‘utopia’ proves more revealing than strict accuracy. Thus Green’s argument – that we are still being bound up in the horizon of the twentieth century – itself displays the traumatized language and thinking that are the deeper symptoms of his diagnoses.

What makes Four Movements so fascinating is precisely the space between the voiceover and the other performative elements. After all, as Paul Ricoeur wrote, “What is at stake in ideology and utopia is power. It is here that ideology and utopia intersect. If ideology is the surplus-value added to the lack of belief in authority, utopia is what unmasks this surplus-value.” If, in this respect, we can take Green’s narration as playing at ideology by relentlessly returning us to the status-quo, perhaps we can also take his images, Cerf’s sound, and the Quaver’s music as so many utopian actors, each pulling at his paving stones to reveal the beach beneath.

]]>

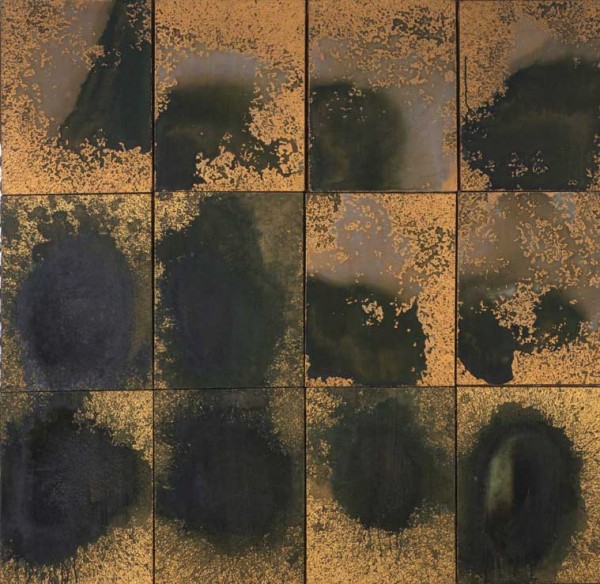

Andy Warhol, Oxidation Painting (in 12 parts), 1978. Via The Brooklyn

One way of appreciating how elusive the descriptor ‘pop’ is when applied to art is to compare it to its corresponding use in describing music: ‘pop’ as in art is different than ‘pop’ as in music. In the latter case, what goes by the name of pop is literally that which is popular, which has a wide audience. Pop Art, on the other hand, refers to the importing of content that is already popular elsewhere, and that becomes significant by virtue of its appearance before the otherwise restricted audience of high art. Thus inscribed within the term ‘pop art’ is the very distance between the artworld and the rest of the social sphere that the historical avant-gardes had, theoretically, sought to collapse. Inscription is the key word here, especially with regard to Andy Warhol, whose early genius it was to be forever playing one side of this divide against the other, to better locate the edges of both.

On the one hand, Warhol’s pop is an obvious attack on art’s presumed autonomy, mocking its assertions of distance and difference from the everyday products of mass culture. This is clear in his Marilyn series, for example, which not only parodies De Kooning’s vision of the same subject, but actually diagrams its absorption into the larger riptide of images that dominates contemporary life. For all De Kooning’s presumptions to critical remove, Warhol seems to be saying, his Marilyn amounts to little more than a print with brighter colors. A similar claim is at work in his description, in his quasi-autobiography, of Bob Dylan as ‘the thinking man’s Elvis Presley.” Here too the pretentious one, shorn of his faith in his own splendid uniqueness, is reduced to the material reality of his position within the landscape of cultural production.

On the other hand, however, and somewhat paradoxically, Warhol’s own work clearly relies on that same distance to generate its own meaning. If, that is, there were truly no difference between the gallery and the supermarket, or the department store, say, it would be impossible to recognize the significance of Warhol’s nomination of these themes for consideration. What’s more, considered formally, his work is not simply interested in popular artifacts, but in the specific process by which they become popular. By representing the repetition, reproduction, and dissemination that transforms products – images, really – into icons, the artist restates the very distance he would deny Dylan and De Kooning. In a kind of parody, Warhol attempts to neuter art’s inevitable appropriation by anticipating it, opening a parallel space on the other side of the divide between representation and lived experience. The early work unfolds by refusing the incorruptible authenticity of a personal vision, insisting instead on its impossibility. Amidst a shabby sea of endlessly reiterated images, Warhol’s diagrams, schematics and dioramas are the negative imprint of art’s historical autonomy, framing its complicity. To this extent, Warhol is realistic.

photo of Marilyn Monroe, Willem De Kooning, Marilyn Monroe, 1954, Andy Warhol, Marilyn, 1962.

To claim this artist for realism is in many ways questionable, and in any case complicated. Still, it does allow us to see in Warhol’s rejection of the dominant, abstract expressionism of his day a strange echo of the earlier refusal of classical expressionism, announced, most notably, by Georg Lukacs in Weimar Germany. Lukacs, writing in 1934, argues that:

As an opposition from a confused anarchistic and bohemian standpoint, expressionism was naturally more or less vigorously directed against the political right. And many expressionists and other writers who stood close to them took up a more or less explicit left-wing position in politics… But however honest the subjective intention behind this may well have been in many cases, the abstract distortion of basic questions, and especially the abstract “anti-middle-classness,” was a tendency that, precisely because it separated the critique of middle-classness from… the economic understanding of the capitalist system… could easily collapse into its opposite extreme: into a critique of “middle-classness” from the right, the same demagogic critique of capitalism to which fascism later owed at least part of its mass basis….

Remarkable about this passage is the extent to which it foreshadows similar, latter-day complaints about AbEx, albeit in a different political idiom. Here is Eve Cockcroft, writing in Artforum in 1974:

The alleged separation of art and politics proclaimed throughout the ‘free world’ with the resurgence of abstraction after World War II was part of a general tendency… By giving their painting an individualist emphasis and eliminating recognizable subject matter, the Abstract Expressionists succeeded in creating an important new art movement. They also contributed, whether they knew it or not, to a purely political phenomenon – the supposed divorce between art and politics which so perfectly served America’s needs in the cold war.

Cockcroft is referring, of course, to the CIA funded, “New American Painting” show that toured Eastern Europe as an example of America’s cultural superiority. Though it would certainly be a mistake to read into Warhol a properly political motivation for his implicit critique of AbEx, it is difficult to miss his focus on the ‘economic system’ that Lukacs found lacking in the movement’s earlier appearance, once we adjust for that system’s evolution. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine a more ruthless assault on expressionist subjectivism than the one pursued by Andy Warhol in the 1960’s. That he could do this without making common cause with the historical, hard-left antagonism says a great deal more about his cultural moment than it does about any political incapacity on his part.

Another way of making the same point would be to note that Guy Debord published The Society of the Spectacle six years after Warhol’s first solo show. It might as well have been a catalog essay; so effectively did the artist illuminate the ‘social relation between people, mediated by images’ that was the centerpiece of Debord’s critique. The terrain of realism had changed, even if that of expressionism had not.

Andy Warhol: The Last Decade, installation view, via Contemporary Art Daily

What then to make of Warhol’s late work? Of his return to hand painting and abstraction? This is the implicit question posed by Andy Warhol: The Last Decade, organized by the Milwaukee Art Museum that closed at the Brooklyn last month. The show is the first survey of the artist’s final years, and, at first glance, the reasons for this delay are clear: the work simply isn’t very compelling. The best pieces are the collaborations with Basquiat and even these feel like limited iterations of that artist’s more successful canvases. When considered against the rest of Warhol’s output however, these works offer an illuminating counterpoint to the process-without-a-subject that produced his earlier, signature pieces. It’s almost as though Warhol had to construct a parallel identity within the field of representation itself before expression became a possibility.

Inside the gallery, Warhol relentlessly pursued his own erasure, presenting installation after installation that testified to the impotence of the artistic gesture. If this amounted to its own kind of intervention, it was only by virtue of its absolute embrace of the new spectacular reality. Fine, we’ve covered this. In his films, however, Warhol took an apparently opposite tack. By choosing individuals he found fascinating, and placing them on screen, he was experimenting with the raw material of an individual identity. What of a person survives the translation to the screen, the shift from quotidian existence to moving image? Conrad Ventur, in a show earlier this summer at Momenta Art, dramatized this question by recreating Warhol’s early screen tests with the same ‘superstars,’ all now significantly older. Running on TV screens scattered around the floor of the gallery, the videos marked the distance between Warhol’s moment and our own. Melancholic and quiet, the videos are absent the youth that had intrigued the artist in the first place, calling attention to what sort of industry it was, exactly, that his factory was creating. As if to underscore the point, Ventur includes looping videos of the songs that played on repeat as the originals were being made.

Conrad Ventur, Screen Tests Revisited, installation view, courtesy the artist.

Warhol’s superstars were scouts, sent ahead of his own person into the slipstream of images whose circulation fascinated him. That so many of these stars did not survive, either literally or figuratively, only bolstered his own efforts to fashion a public existence in perfect congruence with the image-operation that was his favorite subject. Warhol’s many writings in which he presents himself, again channeling Debord, as alienation perfected are not so much a lie, as his friends occasionally claimed, as an attempt to embody the truth of fame itself. “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol,” he declared, “just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.” This, it is important to remember, is demonstrably false – there was a person, Warhol, who was not reducible to his myriad surfaces, no one is, people are not images. Yet, and here is Warhol’s point, images are all we have of anyone encountered via the mechanisms of the culture industry. Thus the problem with the abstract expressionists was not that they were inauthentic; it’s just that authenticity is not an option. And a commitment to this failed strategy on the part of the big men betrayed a pitiable naiveté about the gulf between their persons and the images that played them on TV, or in magazines, or anywhere, really, that they happened to appear. It was this gulf that Warhol highlighted by appearing only on the far side; a performance of transparency which is, by the terms provisioned by the age, technically impossible, and this impossibility feeds back into the man, returning him the agency his predecessors didn’t know they’d given up. Though they’d thought themselves abstract expressionists, the world knew only abstracted expression, and it is there, at that level and with that knowledge, that Warhol’s work begins.

Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat, Sin More (Pecca di piu), 1985. via Art Hag

Warhol’s late forays into abstraction, then, are not all his in the way that Pollack became his splatter or Rothko dissolved into his colors. It was Warhol’s image, his personae, carefully constructed over decades that could now express itself, when there was, at last, no danger of distortion. By religiously refusing to be anything for everyone other than the distilled form of what anything inevitably is, insofar as it is for everyone, Warhol reconstructed a subject on the other side of capital, and it was this that he indulged.

Consider his Oxidation Painting (in 12 parts) from 1978, where, by urinating on the canvas, Warhol demonstrates the impossibility of his own appearance, as his excrement arrives as simply a distortion of metallic paint. The eventual oxidation rehearses, for a second time, the movement of abstraction. When Basquiat painted over Warhol’s silkscreens, expression(ism )is revealed, at bottom, to be merely the embellishment of an already circulating structure, a window treatment on the reified edifice of a tele-visual age.

As always with an artist known for his feints and his diversions, there is a risk in filling up the empty space of his intentions with a corresponding excess of conceptual strategy. To claim, as I have done, that the artist’s late expressionism is not a detour from his early trajectory, but rather its completion – as Warhol’s avatar of pure surface is at last allowed to speak, painting by hand what before he’d produced by automation, for example – is in many ways to violate his own injunction, reaching for a coherence and a depth which he maintained was unavailable. But unavailable for whom? Warhol’s claim was never that depth did not exist, only that it was not available to artists, to the image makers, in the way they might have liked. At the level of reception, on the other hand, a certain depth is required of us if we’re to understand what he was trying to say with his immaculate topography of our remediated silence.

]]>

Gary Hill, Around and About, via arttorrents.org

In the Nature of Language, Heidegger writes:

But when does language speak itself as language? Curiously enough, when we cannot find the write word for something that concerns us, carries us away, oppresses or encourages us. Then we leave unspoken what we have in mind and, without rightly giving it thought, undergo moments where language itself has fleetingly and distantly touched us with its essential being.

Midway through his sensational opening discussion of Gary Hill’s work last night at Electronic Arts Intermix, George Quasha said something similar: “Language reveals itself through atypical use.” The two sentiments are similar, but there is an important distinction between the failure of language to come when we call it, of our finding-ourselves-without-it, of literally being at a loss for words, and it’s consciously atypical deployment. The former is an experience that takes place amidst everyday life, albeit one that pulls us from it, while the later, as Quasha indicates, is a function or strategy of art, or more appropriately, poetry. Thus the distinction is between being subject to language, and summoning it to reveal itself on its edges and amongst its failures.

No one inhabits the edges of language with more grace than Gary Hill. No one makes its failures more alluring. Technically a book launch for An Art of Limina: Gary Hill’s Works and Writings, a new book by Quasha and Charles Stein, (who, along with Hill himself, was also in attendance) the evening is better described as an intellectual and artistic portrait. Both Hill and his collaborators share a deep and abiding fluency with the mid-twentieth century phenomenological tradition; late Heidegger, yes, but also Blanchot. Theirs is a full language, heavy, even; pre-Derrida in exactly the same way Beckett is pre-Derrida. Which is to say that for Hill, Quasha and Stein, language has not yet exchanged its essentially pregnant mystery for a relentless complicity with violence and domination. Language is not yet the enemy it later became, not only for French thinking but for American art as well.

Of course to speak in terms of chronology is almost impossible. Hill and company are making work in the 1980s that engages in a remarkable dialogue with ideas written in France and Germany in the 1950s, whereas other American video, both before and after, takes its inspiration from (chiefly French) thinking done in the 1960s and 1970s. The coexistence of both tendencies in American art from 1970 or so on reminds us of the complexity of the intellectual exchange between Europe and America in the second half of the twentieth century. Far from being a sort of straightforward progression of styles from Marxism to Phenomenology, from Structuralism to Post-Structuralism, each of these terms infects the other, surfacing at various times an in various ways. Thus the actual progression is linked more closely, perhaps, to individual careers – one can say, for example, from Sartre to Levi-Strauss to Derrida and in a certain way come closer to an accurate accounting. Heidegger is specifically absent here but present nevertheless, just not as a particular, bounded moment.

Gary Hill, Around and About, via arttorrents.org

In any case, Hill and his collaborators gentle refusal of the deconstructive tendency in favor of a more classically hermeneutic encounter remains striking in its power and consistency. The incredible eclecticism of art language in the present moment, with its increasingly omnivorous intellectual appetites, is, even over several hundred pages, rarely able to penetrate as deeply as Quasha did in the first five minutes of his introduction. The internal exchange within a given body of thought, even one as notoriously difficult as phenomenology or hermeneutics, produces a language optimized for quick depth. Thus, in his remarkable thematization of Hill’s work and the text that he and Stein have produced to further it, Quasha was able to say a great deal very quickly Should a video or a transcript of the evening be made available I would highly recommend it from start to finish. For my purposes, however, I would like to take up a unique claim laid down by Quasha in order to return, back through Heidegger, to Hill’s work itself.

Quasha proposes that Hill’s encounter with language began in the way he encountered technology. Early in the evening, Hill himself recounted an anecdote about an emotionally-disturbed child complaining of a ‘loss of technology.’ On the one hand, it would seem clear what technology refers to: the actual machinery utilized in the production of the work. On the other hand, though, Hill’s anecdote should give us pause. To speak of a ‘loss of technology,’ is to speak of a lost capacity, of an absence of a certain, but not necessarily specific, kind.

Heidegger writes, in The Question Concerning Technology:

Technology is a mode of revealing. Technology comes to presence in the realm where revealing and unconcealment take place, where, aletheia, truth, happens. In opposition to this definition… one can object that… at best it might apply to the techniques of the handcraftsman but that it simply does not fit the modern machine-powered technology. And it is precisely the latter and it alone that is the disturbing thing, that moves us to ask the question concerning technology per se.

Heidegger is here highlighting the strange nature of modern technology by contrasting it to its historical understanding as a mode of revealing. Hill’s encounter is certainly with modern technology – but is that the technology of whose loss he speaks? Heidegger insists on the lack of a fundamental difference between the two:

What is modern technology? It too, is a revealing… And yet the revealing that holds sway throughout modern technology does not unfold into a bringing-forth in the sense of poiesis. The revealing that rules in modern technology is a challenging, which puts to nature the unreasonable demand… A tract of land is challenged into the putting out of coal and ore. The earth now reveals itself as a coal mining district, the soil as a mineral deposit… The work of the peasant does not challenge the soil of the field… but… (with modern technology) the cultivation of the field has come under the grip of another kind of setting-in-order, which sets upon nature. It sets upon it in the sense of challenging it. Agriculture is now the mechanized food industry. Air is now set upon to yield nitrogen, the earth to yield ore, ore to yield uranium, for example…The revealing that rules modern technology has the character of a setting-upon, in the sense of a challenging-forth.

Thus even though technology remains a mode of revealing, within modernity it is a revealing of specific kind. What distinguishes it is the powerful unreason at work in its demands on nature. It seems to me, then, to say that Hill’s encounter with language begins in the same way as his encounter with technology is to locate three things within these early works: the revealing proper to technology as such, the revealing peculiar to modern technology: this setting upon and challenging-forth, and language. In order to understand how they might fit together requires we take one more step with Heidegger.

Gary Hill, Around and About, via arttorrents.org\

Returning to this kind of revealing proper to modern technology, Heidegger asks:

What kind of unconcealment is it, then, that is peculiar to that which comes to stand forth through this setting-upon that challenges? Everywhere everything is ordered to stand by, to be immediately at hand, indeed to stand there just so that it may be on call for futher ordering… We call it the standing-reserve. The word expresses something more, and something more essential, than mere ‘stock…’ whatever stands by in the sense of standing-reserve no longer stands over against us as object. Yet an airliner that stands on the runway is surely an object. Certainly. We can represent the machine so. Revealed, it stands on the taxi strip only as standing reserve, inasmuch as it is ordered to ensure the possibility of transportation.” (Emphasis mine)

Standing-reserve is thus a sort of phenomenological approach to the availability demanded of commodities and assets under the present conditions of production. What is significant for Heidegger, however is the way in which this fluidity is extracted from nature, challenged-forth by the setting-upon that is proper to the peculiar revelation of modern technology. I would like to draw a parallel between this challenging and Gary Hill’s approach to language. Thus we might say Hill’s work sets upon language, challenges it, utilizing modern technology in an attempt to reveal language as standing-reserve, to remove its standing over us as object.

Consider Around and About, the first work screened last night. In it, Hill puts a different image to every syllable he speaks. He was quick to offer that many images would have done, “not any, but many many.” Watching it, one has the experience of the possibility of a relationship between what is being seen and what being said, as Stein pointed out, without ever being clear if that relationship is actually present. By penetrating the internal mechanisms of language and manipulating them, Hill has revealed them to be ready-to-hand in the same way that the internal mechanisms of agriculture are available to industrial farming. However, and this is key, language does not offer itself as standing-reserve in the same way. Hill sets upon language in the way modern technology sets upon the former peasant’s field, but language cannot be made to yield the way the field can. It cannot be mined. It withdraws.

In the second work shown, Happenstance, we are again overwhelmed by language, as many different streams of text converge at once amidst a multiplicity of images. Modern technology has enabled Hill to challenge language, understood specifically as our capacity to receive it; pushing it to the point we can grasp only its overflowing. Far from being revealed as a resource to be extracted, language appears instead a central absence, beyond our capacity for mastery. Language will not cease to stand over us as a certain kind of object. Hill’s relentless pursuit of its edges, his atypical usage, reveals it, but not in the way of modern-technology, not, that is, as standing-reserve, but instead as something else. Here we arrive at the return of the original, historical essence of technology once again, as that earlier, less determinate form of revealing. This is the technology of whose loss we can speak, and it is the encounter with this technology, this original revealing, that begins Hill’s corresponding encounter with language.

Thus the utilization of modern technology to reveal the impossibility of language’s ever standing-reserve, of its ever being orderable, in that sense, is at the heart of Hill’s enterprise. Language, we find, is proper to that previous mode of technology, of simple revelation, it cannot be modernized, at least not in the way agriculture, or mining, or transportation can. Language persists instead as a sort of horizon of human understanding, and Hill paints the impossibility of its enframing, of its ever being fully set-upon.

Gary Hill, Why Do Things Get In A Muddle? via djdesign.com

Instead, the reverse is true, language challenges us, sets upon us and it is we who risk being enframed by it. This is clear in Why Do Things Get In A Muddle? one of the last works showed last night. In it, performers, including Stein, read a script backwards, but the tape is played in reverse. The result is as engaging as it is uncanny. We can sort of make out the words, but we never lose our awareness of their being something strange and alien about them. The camera rotates endlessly to further distort our access to something like perspective. Language is again made strange; we are distanced from it, but far from enabling us a greater control or understanding, we are revealed instead, perched precariously within it, peering out.

We are now able to more fully grasp what the phrase “Language reveals itself through atypical use,” means in the context of Hill’s work. This atypical use is of a specific kind; it’s a sort of performative rehearsal of modern technology’s relationship to nature, specifically with regards its machine-powered manipulation. Language arrives precisely when, being set-upon, it refuses to appear as standing-reserve. It is only in this reference to this refusal that we can speak of language’s having been revealed. Thus Hill detours through modern means of representation in an effort to trace a return to language and a lost technology.

This loss ought to be melancholic, by all rights, but of course Hill and his collaborators are too many poets for this to be a real possibility. Everywhere their writing is of a wonderful suggestiveness, their turns of phrase so well-tuned as to risk upstaging their intention. But thank God for that, really, as these little bursts of affection are so many reminders, amidst a relatively alienating landscape, of our essential affinity with language and our being at home within it.

If I had one complaint, it’s that three individuals with such an obvious appreciation for poetry and philosophy have made a book that weighs five and half pounds. How such an object is to enter into the daily rhythm of reading and thinking alongside the reams of texts that inspired it escapes me. No matter, if its half as wonderful as listening to Quasha, Stein, and Hill, it will be well worth setting-upon.

]]>

Peter Rostovsky, Olav Westphalen, Anti-Prow, via Art in General

It bears repeating: the belief that housing prices would continue rising forever is as utopian an idea as has ever informed human endeavor. What’s more, all our cynical pragmatism about previous utopias was useless against this most recent and widespread naïveté. Perhaps it was something in the nature of housing itself; the understanding of collective need slowly giving way to an image of the vast sea of humanity furiously pressing against a limited supply, forcing prices ever upward. Squint and it almost makes sense. Of course history is littered with these market utopias, which are even more prevalent than their political cousins. Read Marx in public, however, and you are likely to elicit sympathetic head shakes and a gentle but definitive condescension. The operative assumption being that, unlike the reader of The Art of The Deal, the would-be revolutionary actually believes in the good of humanity. The market fundamentalist, by contrast, is just looking to get rich, a outcome common enough in these parts. The obvious irony is that a great many individuals got very rich indeed off of Communism, but then, no one assumes you’re an aspiring member of the politburo. The extent to which we are willing to accept utopian pretensions turns not on their relative credulity, but on the fate of the faithful. We believed in ever-rising housing prices for the same reason that our ancestors believed in the dictatorship of the proletariat, because it was what successful people appeared to do.

Peter Rostovsky, Olav Westphalen, PROW: The Prequel, via Sara Meltzer

Two installations by artists Peter Rostovsky and Olav Westphalen, PROW: The Prequel and Anti-Prow currently open at Sara Meltzer and Art In General, respectively, offer two competing engagements with these operative utopias, each attuned to their presenting spaces. PROW: The Prequel makes a claim for the essentially commercial nature of artistic production, modeling itself on an independent movie studio and displaying drawings derived from Google’s open source 3d warehouse. Anti-PROW, responding to its non-profit location, covers the walls with texts from manifestos, artistic and otherwise, while also featuring hand drawn images of dead Lenin, dead Che, dead Mao, and Jonestown, among others.

Both shows feature a large centerpiece. PROW offers a complex creation utilizing fans, theatrical lighting, and sheets of fabric to simulate a massive fire in the center of the room. Two automated string instruments herald its intermittent eruption. Starting up every six minutes or so, and carrying on for about two, the blaze is at once quite striking and obviously artificial. Anti-PROW, for its part, has a number of ladders, open and strapped to one another; the structure having been arranged and painted to reflect the size, shape and color of the fake fire located across town.

Peter Rostovsky and Olav Westphalen, Anti-Prow, via Art in General

Each exhibition aims at sketching the presuppositions underlying their individual homes. In PROW’s case, the independent movie studio model is offered up as the highest, most respectable form of commercial art. The open source drawings, channeling the traditional world-as-model aspiration of architecture as well as contemporary wiki-idealism, are so many gravestones for the utopian promise of the marketplace. Similarly, Anti-Prow’s declared negation of the other, commercial PROW presents the not-for-profit space as a counter-offer, the only true space for art. Its drawings of dead believers similarly mark the end point for a certain anti-commercial strain of thinking.

Especially valuable here is the strong positioning given to not-for-profit spaces in the mapping of contemporary production. Long considered a sort of appendix to the more essential organs of museum and gallery, Anti-PROW offers up the 501©3 model as heir to a very specific vanguard tradition. Though perhaps darkly humorous to anyone familiar with the deep indignities carried by that particular tax-status, it’s not a point that can be quickly dismissed. With the standing of the contemporary museum radically compromised there is a vacancy to be filled. It remains to be seen, clearly, to what extent not-for-profits can effectively take up this mantle, but it is certainly an important moment for them, and one that Anti-PROW highlights by engaging so openly with it.

Peter Rostovsky and Olav Westphalen, Anti-Prow, via Art in General

This is not to say that I see a clear or material echo between vanguardist movements and non-for-profit production. The two are perhaps better situated on opposite ends of the spectrum, as bookends for the great godbeast capital, one it’s (declared) enemy and the other it’s obedient pet. They have, though, potentially been forced into the same corner, or at least it’s a question worth begging. Interestingly, PROW offers a somewhat more nuanced engagement with commercial space, and the presentation of the indie-movie model as more collective and variegated seems a more hopeful suggestion than it might at first appear. It does not seem, ultimately, that PROW is as hard on the commercial enterprise as it’s counterpart is on the not-for-profit. The former is generally held to be still in the moment of its becoming, while the latter is relegated to a violent and archaic past.

Still, there is the question of the centerpieces. I think their chief virtue, and its not a minor one, is to linger precisely as questions. The formal and visual congruence between the two is certainly the most classically arty-crafty, pretty-pretty achievement to be found in either exhibition, especially if you see the Art in General show first. In this case, the moment of conflagration is one of lovely recognition, like fireworks bursting into the shape of a star. There are other patterns here too, of course, the blue-collar overtones of the ladders contra the constructed, superficial spectacle of a fake fire. But the strongest reading is one that takes the apparent similarity seriously, as a sneaky gesture towards art’s final complicity being chiefly, if not exclusively, with itself. It does not matter so much, the PROWs whisper, whether one is making money or not; the creative effort, in its reaching and striving, is always, always more than the sum of its parts.

]]>

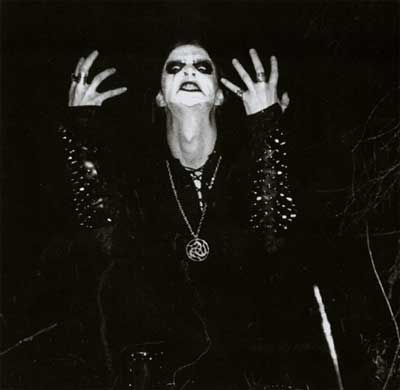

Until The Light Takes Us, dir. Audrey Ewell and Aaron Aites. Varg “Count Grishnackh” Vikernes, from Burzum and Mayhem, in prison, courtesy Variance Films

The visceral extremity of a really wacked-out subculture is the sociological gift that keeps on giving. No matter your critical project, it will likely be possible to project it onto whatever awkward, formerly adolescent outcast you can dig up and put in front of a camera or tape recorder. Until the Light Takes Us, a recent documentary about the Norwegian black metal scene in the early 90s, seems almost painfully self-conscious about avoiding this sort of instrumentalization, and this is certainly the best and worst thing about it. Seemingly allergic to even the most basic documentary structure, UTLTU only grudgingly supplements the accounts of its subjects with desperately needed context or information. At its worst the film is a rudderless pretension, wandering from one needless, uninformative shot of someone traveling to a similar one of someone else walking from one unidentified place to another. Its precious, boring, and invested in a comic portentousness which serves chiefly to heighten the already cringe-worthy proclivities of its protagonists.

The result is two-fold. On the one hand, yes, you will likely spend a good portion of the film tallying up the myriad examples of rank amateurism and bemoaning what might have been. Get over that, though, and you will find, for all the lack of classically documentarian pleasures, one does emerge from UTLTU with a genuine feeling for its two leads, Varg Vikernes and Gylve Nagell, both significant figures in the moment under consideration. This feeling is not so much sympathy or understanding as it is the sort of queer clarity that comes from actually spending time with someone. Simply undermining ideological assumptions, be they those of the movement’s originators or of the film’s audience, is a less journalistic outcome than might be hoped for, especially for such a deliciously fascinating topic, but it is an important one. Indeed, the longer I thought about UTLTU, the more I appreciated the filmmakers’ almost pathological reticence to insert themselves or their ideas into the overall framework of the film, frustrating though the experience could be.

For those unfamiliar, the second wave of black metal chronicled in UTLTU took place in Norway from 1990-1994. Growing out of speed and thrash metal in the 80’s, Norway’s black metal scene became a sensation when it was linked to numerous church burnings and multiple murders. The most famous of which was the killing, by Vikernes, of Øystein Aarseth, known as Euronymous.

It’s the complementary portraits of Vikernes and Nagell that ultimately carry the film. Playing the roles of ideologue and artist respectively, their combination depicts with rare clarity the spectrum of sub-cultural radicalism. Vikernes, still imprisoned for the murder, is a powerful intelligence. Articulate, insightful, and by far the most compelling presence anywhere in the film, Vikernes also ends up as the most important primary and secondary source for the majority of the narrative. Invested in black metal chiefly as a vehicle for reprehensible ideas about race and nationalism, Vikernes seems totally unreconstructed; his incarceration having only deepened the paranoid hatred at the root of his thinking. There is something of a moral hazard in letting such a figure serve as his own interpreter, and anyone familiar with the extent of Vikernes’ ideological legacy will be likely be unsettled by its relatively partial presentation here.

Nagell, for his part, and by contrast, seems genuinely, almost sweetly, all about the music. When prodded to talk about the culture and events surrounding black metal, he can only mumble frustration at its becoming “trendy,” and offer a sort of shy sadness. When discussing music or art of any kind, however, he becomes animated and passionate, and it’s a shame the film doesn’t find more time for these excursions, as Nagell proves an incisive and fascinating critic. As it is, entirely too much time is spent following the man around hoping he’ll say or do something interesting or significant, which he rarely does.

The most illuminating moment on offer is when these two are asked to comment on each other. Both offer a cautious respect and hint at a mutual incomprehension. Vikernes admits that he doesn’t understand Nagell, asserting that he operates by some inner logic that he can’t penetrate. This would be funny if it wasn’t also quite so sad. Nagell is hardly some great mystery, he is simply an artist, sincerely invested in making music above all else. Of course this is totally inscrutable to a fervent ideologue like Vikernes, for whom black metal is inseparable from the larger project of Odinist reaction. That these two together should have anchored a movement says a great deal about the different sides to the black metal story and the different types that went into shaping it.

One is tempted to extrapolate and say that all art-centric subcultures operate in the spectrum bookended by Vikernes and Nagell, in the space between a radical ideology and a (relatively, relatively) autonomous aesthetic. Black Metal would then be a far-right instance of a pattern common also to genres like Punk and Dub, which offer a similarly elitist (because anti-pop) combination of words and music but in an ostensibly different direction. On the one hand it’s no surprise that the powerful narcissism of the little musical differences between punk and metal diverge much more vividly at the moment of their political reckoning. On the other hand, metal has always had the better musicians and punk the better ideas, and if that seems like an overly broad or bias statement, maybe that’s why UTLTU works so painstakingly hard to avoid arguing anything so definitive. The drawbacks of this approach, detailed above, are not unique to this film, but its virtues certainly are, and if that makes it less than enjoyable or impressive, it also makes it infinitely more valuable.

]]>

Seth Price, installation view from 2009 Reena Spaulings exhibition, via Contemporary Art Daily

When I was younger I had a friend whose family only listened to the oldies station. Riding in their mini-van, I remember wondering why it was that, song for song, the old songs sounded better than the new ones. Furthermore, I couldn’t figure why, despite this fact, I certainly didn’t want to be listening to the oldies station. It only occurred to me later that the music sounded better because it was better, having been sifted from two or more decades of pop hits. This was a significantly larger sample size than was available to contemporary culture industry outlets, but the latter’s claim to the new still made for more compelling listening, day in and day out.

Perhaps this quality-gap accounts for the lazy, listless pleasure with which we come across retrospectives, year-end lists, and the various other summaries scrambling to define a given annum. We are pleased because the quality is higher, but also a little bored because, well, it’s already over. At the extremes, this dynamic accounts for both the comfortable fatigue of art history textbooks and the animated outrage of an awesomely bad, present-tense failure.

The White Columns Annual aims to avoid the pitfalls of the year-end genre by presenting itself as “an exhibition based on [one person’s] experience of looking at art in New York in the previous year.” Aiming at a “format [that] inevitably encourages [a] highly subjective and deeply personal response to the realities of viewing art in New York,” the not-for-profit hopes to offer one unique take rather than a summary of the whole thing. It is perhaps a credit to the various curators, or ‘selectors,’ as well as the selector selector, that the Annual has taken on a slight bit of the authority it never aspired to in the first place.

Looking Back, installation view, via White Columns

Primary Information, this year’s selector and a New York-based non-profit “devoted to printing artist books, artist writings, out of print publications and editions” does little to jeopardize this positioning, but nor does it do much to expand it either. The show doesn’t feel particularly subjective, but it does feel smart, even a little calculated, and how you feel about the stated goal of the Annual will probably determine how you feel about this edition. If, for example, you share Holland Cotter’s belief, carefully quoted in the press release that “The White Columns Annual does … what the Whitney Biennial used to do: it reconsiders a slice of art’s immediate past. … The idea is welcome affording a chance to linger over art that was seen earlier only in rushed visits, missed entirely or enthusiastically remembered…” than you will be pleased to find a number of the significant hits from 2009 available here again.

If, however, you sympathize, as I think I do, with the original, stated goal of the Annual, you cold be forgiven for hoping for a slightly more, well, highly subjective and deeply personal presentation. In this sense, it is hard to see Looking Back as particularly revelatory as to what Primary Information’s year in art was like, given their mission statement. Personally, I would have been fascinated to see what that show would be like. As it is, the only piece here that really seems to reflect the specificity of the selector is a three-dollar zine compiling every negative review run by the Times over the previous year. It’s a maddening document, frequently illegible and ultimately quite compelling. Partly an exercise in determining the moment a review moves from reportage to criticism, and then again towards negativity, either implicit or otherwise, it is most definitely a delightfully unique take on the past year. Cynically emblazoned with a photocopied ARTFORUM title across the back, the zine fully justifies whatever remains of the Annual’s initial instinct towards subjectivity.

But it is an Annual after all, not a diary, and the real point is that Primary Information does a thorough and elegant job revisiting the year that was. A lot of the highlights are here; Dorothy Iannone, Seth Price, Reena Spaulings, and the consensus favorite from YTJ, Cyprian Gaillard’s Desniansky raion. The last was especially gratifying to re-encounter a second time in a less hectic setting. Much praise has already been heaped on Gaillard, making his inclusion here an obvious choice, the most obvious one in the show, in fact, but as obvious choices go, it’s likely the best that could have been made. Desniansky raion is evidently excellent in the way that defeats any backlash or fatigue; precisely the sort of work that shows like this are made for.

Looking Back, installation view, via White Columns

The inclusion of one of Seth Price’s calendar paintings is also well-taken. Made in 2003 and 2004 but not widely exhibited until 2009, (when they were shown at, where else, Reena Spaulings, but that’s another kettle) the calendars provide a fascinating glimpse of a moment when Price’s conceptual thinking and artistic output were maybe not quite so separate as they are today.

If there is a signature piece here, though, its Georgia Sagri’s. In a videotaped performance, the artist appears outside of some elite event, likely art related, and proceeds to recite a singsong chant at the top of her lungs. “Is everybody having fun here/I’m asking you/I’m asking you” she repeats again and again until she’s exhausted, out of breath and leaning against an unlucky car trying to sneak past.

At first look, its a shallow gag, obnoxious and obvious and not immediately interesting. But when you consider the year that was, the collapse of the economy, the cratering of the art market, the general social and political madness, and then look around at the neatly executed, almost chilly art objects that make up the rest of the Annual, Georgia’s begins to seem like the most honest expression in the room.

Certainly at the height of the booming aughties art traded some of its political edge for an abstract criticality and the desire for a really good time. Everybody was having fun, not only here, but everywhere or was at least suitably afraid to admit it if they weren’t. Sagri’s desperate refrain, rendered on a small screen with headphones, captures vividly the creative and financial hangover many of us have yet to fess up to.

]]>

Brody Condon,Case, 2009 photo: Kristianna Smith

The fetishist is doomed to mistake a part of something for the whole. Thus, for example, a foot fetishist treats a foot the way another might the entire body. The techno-fetishist, for their part, takes technology for the whole of the social order, a step we typically identify with a certain optimism, even utopianism – as in the case of Marshall McLuhan or Isaac Asimov. Cyberpunk, however, was the same techno-fetishist gesture in the opposite direction, presenting a social landscape destroyed by the aggressive proliferation and hybridization of technological evolution. In the case of the genre’s archetypal text, William Gibson’s Neuromancer, technology is first and foremost engaged in exploding the category of addiction, sentencing the body to a dependence on the products of an ever-more restless and creative mind.

The characters’ confinement to their heavily augmented physical selves is juxtaposed against their ability to ‘jack in’ to cyberspace, a sort of astral projection famously described by Gibson as:

A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of operators, in every nation… A graphic representation of data abstracted from banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding.

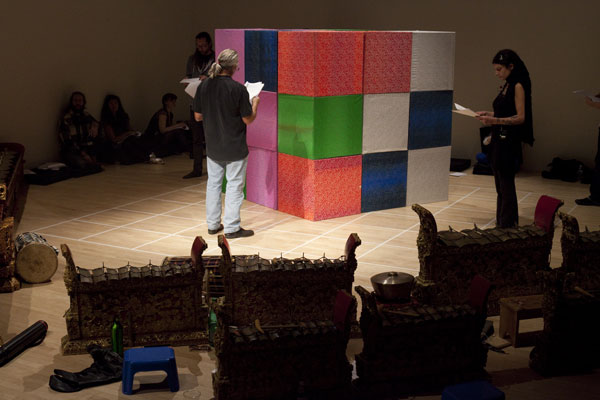

At the beginning of the book, our anti-hero, Case, has been cut off from cyberspace – his body made incompatible – as punishment for sins against a past employer. Brody Condon, (who, full disclosure, is a friend) in his recent staged reading of the novel at the New Museum, effected a similar isolation for his audience. Each time Case, read by Condon’s stepfather Ray ‘Bad Rad’ Radke, would jack in (his prohibition is lifted early in the narrative, though threatens to return) a twenty-two piece gamelan band, situated between the audience and the actors, began to play. At the same time several large, colored cubes were moved around the playing space in what the artist has described as a ‘parody of this idea of a space where we would fly through information.’

Brody Condon, Case, 2009 photo: Kristianna Smith

The experience of watching these transitions was a delightful absurdity. It was quite impossible to hear the text over the gamelan, and we were left regarding actors stuck in a strange tableau, surrounded by slow moving colored cubes. It effectively conjured the feeling of outdated special effects; indeed, Condon has approvingly quoted Bruce Sterling, another cyberpunk originator, as saying “the idea that the virtual is somehow philosophically separate from the actual, it’s a period notion. It’s done.”

Condon’s recent work has displayed a rigorous fascination with role-playing, performance and identity. At its most successful, as in Without Sun, and Twentyfivefold Manifestation, this work cracks open the process of projection by which we identify and inhabit a given state, laying out, as if in inventory, the constitutive moments that add up to the assumption of this or that identity. In Without Sun, the goal is a sort of performative surgery – the disentangling of voice and movement so that each might be experienced with a degree of separation. Twentyfivefold Manifestation, on the other hand, channels Bruce Nauman in its positing, as a sort of experimental hypothesis, a specific, mystical relationship between art and its public. By adding eighty, live action art worshippers to the Sonsbeek International public sculpture exhibition in the Netherlands, Condon transformed the space into a vivid exploration of two different roles for art’s audience and even, in some cases, set them against each other; as when the LARPers chased off visitors from their respective fetish objects.

Case continues this trend, only this time the role under examination is Condon’s own. The artist has presented a startling cartography of the encounter between an early, formative experience –his receiving a copy of Neuromancer from his stepfather – and his own artistic process. Foregrounding his own position as artist throughout the performance by directing the actors, moving the cubes, announcing the breaks, and conferring with his collaborators, Condon has quite literally broken down, piece by piece. his own role for the audience to examine.

Brody Condon, Case, 2009 photo: Kristianna Smith

Consider the casting of Radke to play Case. On one level the parallels are quite straightforward, both men are in recovery, both are former hellraisers, etc. But on another level, Condon’s own invitation to Radke to step back into the world of Neuromancer, and the noisy, constructed cyberspace he has devised, offers a distinct analogy to the role of the Wintermute -the narrative’s semi-omnipotent artificial intelligence – in allowing Case back into cyberspace. In this way, Condon is dramatizing the artist’s relationship to personal history, offering himself as analogous to the puppet-master AI, standing simultaneously inside and outside his own story, manipulating memories, and creating the conditions by which an old vision of the future takes place a second time.

The separation implied by Sterling’s ‘period notion’ of virtual cyberspace is itself as mythical as the artificial intelligence whose inhuman laughter inhabits it. Certainly the gamelan ensemble is there to underline Gibson’s archaic, exotic rendering, but the parody, by dint of the performance, extends to encompass the artistic process itself. Gamelan, which is of profound importance in Javanese rituals, sets off not only Gibson’s cyberspace as mythical, but Condon’s performance of art-making as well, as he slyly lampoons his own confessed obsessions with transcendence and projection.

Brody Condon, Case, 2009 photo: Kristianna Smith

The point is thus not simply that there is now enough distance between us and Neuromancer that we can recognize its wanton myth-trafficking. Nor is it that art-making amounts to little more than mythologizing one’s personal history, with the artist acting as a sort of all-powerful artificial or inhuman intelligence vis-à-vis his or her own unique experience. (again: revealing mystic truths) It is rather that, for an artist, like Condon, coming to consciousness in the early eighties via texts like Neuromancer and performance works like those of Ann Hamilton, there is a distinct congruence between the techno-fetishism that produced Gibson’s vision of cyberspace, and the body-fetishism behind performance-based artistic production. Both aimed at a certain transcendence and trafficked in a certain faith, and both were formative in creating the artistic identity that Case so effectively interrogates.

In dialogue with Performa’s thematic Futurism, Condon’s Case appears as a ritualized performance of longing for a certain, adolescent idea of things to come. Its a bittersweet nostalgia, one aimed as much at performance itself, as it is at the transcendent space of a more broken future.

]]>

Shana Moulton, The Undiscovered Antique, via Art in General

When, some years from now, the current age finds itself the subject of satire or history, the pluralization of disciplines serving as titles will find itself marked for ridicule, comment or both. We are a people in love with a multiplicity of accountings, endlessly delighted by cartographies, geographies, mythologies, urbanisms, heterologies, eschatologies and the like. We are especially pleased when one of these fancy multiples is paired with a term or an idea that is initially counter-intuitive but ultimately poetic, evocative or otherwise pregnant with meaning. Two exemplary personal favorites in this pantheon include Cartographies of Desire, and Echographies of Television, though to this day I am still not certain I know what the second one signifies.

Why are these syntactical contortions so prevalent and so pleasurable? Perhaps the legacy of a certain postmodernism accounts for some of their plenitude. This strain fancied itself capable of laying out, side by side, any number of divergent, and at times even radically hostile, vocabularies. These competing cognitive maps could then be compared dispassionately, assessed not on the merits, but perhaps as moments of radical congruence – despite the inevitable performance of incommensurablity playing out in practice. The underlying appeal is the distinct intellectual pleasure in structure, compounded, in this country, by the simultaneous arrival (in 1966) of both structuralism and post-structuralism together; the fetish and its cure taken at the same time.

Rancourt/Yatsuk, Phase IV, via Art in General

We can see the legacy of both moments at work in the title of the show currently at Art in General, Erratic Anthropologies. ‘Anthropologies,’ captures beautifully that distinct rush of mastery at work in the structuralist encounter, while ‘erratic’ carefully undoes that same authority in favor of the willed incapacity that marked not just post-structuralism, but all the posts, post-colonialism, post-feminism, and most other post–modernisms taken together.

As it turns out, anthropology is an altogether appropriate description of what’s taking place down on Walker street. Over the course of AIG’s two floors, artists Rancourt/Yatsuk, Shana Moulton and Guy Benfield deploy that discipline’s unique mixture of consideration and contempt on different aspects of contemporary society. Each work stands alone as an installation, but also has a performance element which ties in with Performa.

Rancourt/Yatsuk give us Phase IV, a sort of set-piece installation of a failing housing development in southwest Florida. At the performance last night, the developer, Don Donavucci burst from a paper covered container dressed like an Egyptian pharaoh to hawk the housing development to the crowd. Once inside the half-built house, patrons were encouraged to sign a piece of paper to get in on the development as soon as possible. Having been plied with cheap champagne and terrible, terrible live muzak, we were now offered further refreshments, namely water, whiskey and meatballs. This last combination was a particularly deft touch. It’s an impressive installation, most notably in the presence of a small, manufactured pond in the corner of the gallery behind a wall of fake plants. The pond is lit intermittently by a light linked to a sound installation that alternates between jungle cats mating and ‘the dying market calling out desperately the features and amenities that once made it great.’

Rancourt/Yatsuk don’t seem overly concerned with illuminating the underlying causes of the housing crash so much as they are content to lampoon in broad strokes the absurdity of the claims and personalities involved. This is perhaps less negative than it reads. Too often our pursuit of the conditions of possibility for this or that event moves us too quickly past certain, necessary judgments. No doubt there are deeply satisfying political and economic trends and far-reaching historical proclivities lurking behind the housing bust, but there was also the day-to-day greed, deceit, and general reprehensibility of developers like Don D. In this respect Rancourt/Yatsuk offer us a situation which is considerably less far from the truth then we would imagine, as many of the stunts and tactics utilized here are pulled directly from the playbook of south Florida real estate aspirants.

Shana Moulton, The Undiscovered Antique, via Art in General

Shana Moulton’s contribution The Undiscovered Antique stages a sort of faux pilgrimage to the set of Antique Roadshow for the purpose of appraising an ambitious commodity. Cynthia, Moulton’s alter ego, hopes to uncover a valuable piece of Zuni pottery but ultimately finds herself in possession of a motorized footbath made by Avon. The entire aesthetic of the installation and performance is appropriately hideous; awful colors, vaguely menacing box-store massage tools and more terrible music give us a specific sense of the spectrum of consumption here under attack. Moulton’s use of projected video in performance is particularly accomplished, as she interacts quite seamlessly with the fabricated, two-dimensional landscape.

The engagement here is with that mixture of new-age spirituality, commodity fetishism and cosmetic, self-help culture that has become so prevalent in recent years. Cynthia herself is all surface, a placid sort of reactive consumerist everywoman, especially in the installed work. In performance this character is complicated somewhat by a sort of oblivious megalomania and a sudden and vicious assault at the hands of some unknown object, leading her to bleed pink.

Guy Benfield, Night Store. via Art in General

Lastly there is Guy Benfield’s Night Store, installed in the first floor, store front gallery. Of the three installations, Benfield’s work appears as the least calculated and offers a decidedly messy counterpoint to the upstairs examinations. Haunted by the phrase ‘the trauma of pottery,’ Benfield has recreated a 1970s kiln and filled it with reflective materials, dance lighting, and a fog machine. At the performance, Benfield, dressed in a wig, moved bits of broken pottery in and out of the kiln while extremely loud house music and bits of voice-over were mixed by a DJ. Videos playing on loop depicted Benfield wrestling with different pots in what appears to be a ceramics workshop someplace.

Keeping with the theme, most everything in Night Store is ugly, but it’s a shiny, sparkly ugly in comparison with Moulton’s southwestern K-mart ugly and Rancourt/Yatsuk’s pre-fab crap-o-rama. What is nice about Benfield is that he doesn’t seem to hold his object at quite the distance the others do, allowing himself to inhabit more honestly the universe he is portraying. Ruminating on the ‘trauma of pottery,’ makes Night Store more personal and intriguing but also, correspondingly, less accessible and clear than the other work on display.

All three installations flirt with a smug, unthinking superiority, but each pulls back at key moments to avoid falling into rote denunciation. The plate of meatballs offered by Rancourt/Yatsuk and Guy Benfield’s decidedly compelling DJ accompanist both somehow disrupt the smooth narrative of objective distance. For Moulton’s part, Cynthia’s physical presence stands as a check against looking too far down at the lifestyle being examined. There is, finally, an impressive harmony between the three major elements of Erratic Anthropologies, as well as a refreshing lack of pretention, anthropological or otherwise. ]]>