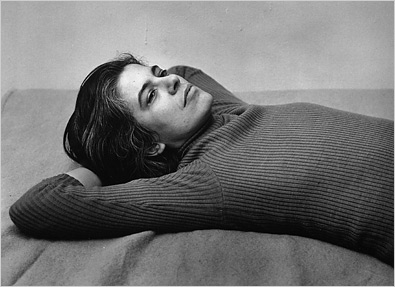

Sontag, 1975 by Peter Hugar. Courtesy of The Susan Sontag Foundation.

As Consciousness is Harnessed to Flesh: Journals and Notebooks 1964-1980

Susan Sontag, ed. by David Rieff. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012.

As Consciousness is Harnessed to Flesh: Journals and Notebooks 1964-1980 is the second volume in the three-part series that comprises Susan Sontag’s journals and notebooks, and follows Reborn, published in 2008 to apprehensive reviews. David Rieff, who edited the series, writes in the foreword that if Reborn can be seen as his mother’s bildungsroman, the equivalent of her youthful literary hero Thomas Mann’s Buddenbooks, then As Consciousness might in turn be seen as “the novel of vigorous, successful adulthood.” The book, of course, is not a novel, but a notebook — a collection of ideas and diaristic episodes, possibly written with the future goal of an autobiography or large autobiographical novel in mind. As a result, this second volume, saddled with a rather cumbersome title (one of Sontag’s notes in the margins of 1965) and weighing in at a hefty 500+ pages, is unlikely to be read cover to cover with much enthusiasm by anyone not already a Sontag aficionado. The book is notational and elliptical at best, brimming with vague pronouncements (“The only acceptable life is a failure”); unanswered questions (“The autobiography of a guru? How do I feel about sublimation?”); fragmentary ideas; borrowed quotations; to-read and have-read lists; and enigmatic, often poetic, monads (“A spy in the house of life”).

That said, As Consciousness does manage to reveal an adult Sontag very much consistent with the budding adolescent intellectual we met in Reborn — self-critical, categorical in her tastes and opinions, deeply anguished, and always, always at work. The very nature of these journal entries attests to the constancy of her mind and her efforts, although she is self-aware enough to realize that the psychological underpinnings of this ambition may be undesirable. “I valued,” she writes, “professional competence + force, think (since age four?) that that was, at least, more attainable than being lovable ‘just as a person.’” The quotes around “just as a person,” not to mention the “just,” are telling, implying not only an unfamiliarity with, or suspicion of, the concept of being loved merely for who one is, but perhaps also a twinge of disdain for the notion of not being proficient enough in a particular métier to be loved for a reason.

Perhaps at the urging of her therapist Diana Kemeny, Sontag spends a good deal of this notebook examining the roots of such feelings in her childhood, finding her mother — an alcoholic who, she believed, equated her daughter’s happiness with disloyalty — in part to blame. Later, Sontag writes that the familial roles in her childhood were perversely inverted, as often happens in the homes of alcoholics.

This inherited dysfunction, not surprisingly, manifests itself in Sontag’s later relationships as feelings of subjugation, as well as sexual inadequacy. At the opening of the book, her tumultuous relationship with the Cuban playwright Maria Irene Fornes, whom she calls “I” or Irene, appears to be ending. Sontag is devastated — penning strange, flatline statements such as “There are people in the world” and alluding to Irene’s icy stonewalling: “There is no responsiveness, no forgiveness in her…Even a grunt of assent ‘violates’ her.’” And what seems even harsher about this rejection is that Sontag blames at least some of it on her deficiencies as a lover. “Self-respect,” she writes (her italics), “It would make me lovable. And it’s the secret of good sex.”

By 1970, however, she seems to regain some happiness and stability or “mastery,” as she calls it, with C (Carlotta), calling her “the first big intellectual event (this past week) since my trip to Hanoi.” Despite this self-professed mastery, however, Sontag’s vulnerability in love is still in full force. Indeed, gone in these entries is any trace of the self-assured critic; in her stead is a desperately insecure schoolgirl, chastening herself before a mirror: “I must be strong, permissive, unreproachful, capable of joy (independently of her), able to take care of my own needs (but playing down my ability, or wish, to take care of hers).” So much calculation and performance! And yet these feelings of insufficiency do not seem to cloud her joy. Instead she writes that at last she is no longer “busy dying” but “busy being born” — a bright, if not fraught, echo of her exhilarated teenage discovery of lesbianism in the first volume of notebooks, in which she famously declared she was reborn and then inexplicably married Philip Rieff.

For someone so desperately seeking love, however, Sontag could sometimes be a rather cold, withholding mother. She admits that she refused to breastfeed David as a baby in order to vindicate her own mother, who did not breastfeed her. When David as a young boy despairs that he is not as precocious as his mother was when she was his age, Sontag does not answer as one would expect her to — assuaging a child’s insecurity with a white lie — but instead simply lets him sit with the unhappy comparison.

While the bulk of As Consciousness, like Reborn, turns inward in self-examination, Sontag does give us glimpses of the larger world, particularly in May of 1968, when she is invited, as part of a delegation of American antiwar activists, to North Vietnam by the North Vietnamese government. Here, as we rarely do in the book, we get to see through her eyes rather than into them:

A bare room, a low table, chairs. We all shake hands, then sit down. On the table: two plates of half-rotten green bananas, cigarettes, soggy cookies, a dish of paper-wrapped candies from China, tea-cups.

…

The first few days I am constantly comparing the Vietnamese with the Cuban revolution….And almost all my comparisons are favorable to the Cubans, unfavorable to the Vietnamese — by the standard of what is useful, instructive, imitable, relevant to American radicalism.

Ultimately, though, it would not be this trip that changed Sontag’s attitude toward Communism. Instead, Rieff tells us in the foreword, it was Sontag’s close relationship to Joseph Brodsky that eventually motivated her to publicly recant her faith in Communism’s liberating potential, not just in its various iterations around the world, but wholly, as a system.

It is surely unfair to read a private diary in the hopes of liking its author. After all, we turn to our own diaries, if we keep them, more often when we are unhappy than happy. What, then, is the value of reading such private volumes, besides voyeurism? Perhaps the conscientious reader can derive some delight in linking up Sontag’s nascent ideas and notes with her essays (I, for one, found her admission of enjoying the sight of “deformed people” interesting considering her defense of Diane Arbus’s work as not sensational in On Photography); but even the casual reader can find some charm or bemusement in the fact that one of our greatest public intellectuals worried about her “fat legs” and kept lists of her likes (urinating, tall people) and dislikes (Robert Frost, German food), as a child would. Sontag uncensored, it turns out, can be as playful as she can be pitiable.

In the end, however, it may be what Sontag doesn’t write that reveals the most about her: most notably, her metastatic, stage-4 breast cancer — either her diagnosis in 1974, her radical mastectomy, or the harrowing regimen of chemotherapy and immunotherapy she underwent in the following years. For someone who has so much to say about everything, she has surprisingly little to say about this very grave matter. If she mentions it, it is brief or obscure, at times requiring David’s editorial hand to explain to the reader, This is a cancer reference. In 1976, she writes one image, “Surgeon’s green hospital shirt,” nothing else, and a few weeks later, she is immediately back to Beckett, Woolf, and the declaration that American poetry is weak — it contains no ideas. A few more pages in, she quotes an intern at Memorial Sloan-Kettering who calls cancer “a disease that doesn’t knock at your door first.” Not a particularly profound or illustrative statement, but that, oddly, is where Sontag begins and ends her thinking on the subject.

Compare this, say, to Joan Didion’s approach to her husband’s and child’s diseases in The Year of Magical Thinking, in which the very act of research, the wishful work of accumulating facts and statistics, helped to serve as a psychological buffer against death. Granted, she herself was not ill, but certainly she was terrified at the prospect of losing her dearest and nearest. Was Sontag in denial? Was she trying to distract herself from the physical suffering, the fear, with her work? Both seem likely, and reasonable, but the cryptically flat nature of her descriptions (“Changes in the body, changes in language, changes in the sense of time”) read oddly, revealing a bizarrely uneven equating of a life-threatening illness with her usual intellectual preoccupations, as if the former could not, without warning, simply wipe out everything. Perhaps this is how she survived, by dwelling on life as it was and insisting that life remain so. But such circumlocutions — for this reader at least — suggest that the true heart of these notebooks and of Sontag’s character lie not in what we see on the page, but rather, in what we can only limn in its white inviolate spaces.

]]>

George Boorujy, Fugue, courtesy of the artist

George Boorujy has exhibited widely in the US and abroad and is represented by PPOW Gallery in New York. Born and bred in New Providence, New Jersey, he now lives and works in Brooklyn. Debora Kuan visited his studio in Gowanus recently to discuss realism, the animal gaze, and our primal need to decorate. They continued their conversation over email.

DK: I am interested in the confrontational aspect of your animal portraits—as you have called them—since giving each animal that kind of subjecthood raises them to the status of individuals. Is it your intention to reverse a hierarchy in the viewer’s mind, since the human beings that occupy your images are not given the same kind of status? They seem subordinated to the narrative, whatever it may be.

GB: The word “confrontational” comes up a lot with the animal pieces. It’s funny, I never really intended them to be confrontational. But I do want the viewer to confront the subject. The gaze is so important in that regard. It changes the experience to one of interaction rather than simple observation. We use animals for so much—for stand-ins, symbols, labor, companionship, food. I want people to think about what they are, how they’ve been formed to do what they do. I don’t want to put animals above people, but we do live together, and this is their planet as well. That sounds SO hippie, but whatever.

When it comes to depicting people, it’s tricky. Viewers already bring so much to the table as soon as they look at another human being that the image and what it’s about can be overshadowed by that. Really my work is all about how we fit into the environment, and how we interact with it—I want to show how we are part of it. So maybe the people become a little smaller because they’re usually fitting into a whole. Although I have done a couple of human portraits, but those are stripped of their expected contexts, and I guess they’re presented more like animals. Which is what we are.

DK: It must be a primal, naturalistic impulse to want to draw animals or things observed in nature—I’m thinking of cave painting, of course, and ancient forms of art. But also, every little kid begins life by drawing. Drawing is our first “written” language in a way, yet somewhere along the way, most of us stop doing it.

GB: In a way I’m still drawing the same stuff I was when I was five! I always drew animals, like most kids, but I guess I just never grew out of it. When you get older, there’s this idea that if you’re making art it also has to be more “adult” or “heady” or something. But there is something primal about drawing, something pre-language. I think there is an impulse to depict what’s around us. Maybe it is to understand it better or internalize it on some level? I don’t know.

Archeologists always talk about how cavemen were trying to attain some spiritual connection with or power over animals by depicting them. Maybe that was true some of the time. But also I think they were just doing it to do it, just decorating, adorning. Sprucin’ up the ol’ cave, so to speak, like, “Hey, wouldn’t it look so nice if we put horses on that wall?! Let’s brighten up this place!” I guess that’s a bit Gary Larson.

DK: “This cave is morose!” I can see that. Or it’s just the simple recording, note-taking aspect: “Today I saw this woolly mammoth and tried to hunt it, but the damn thing got away.” Your choice to work with paper, rather than canvas or another material, seems to speak to that notational quality too. Also it aligns you with nature illustrators. Can you talk about this decision?

GB: Paper takes itself less seriously than canvas. It allows the viewer in more. Initially I started working with ink and paper because it was faster than oil. I was too impatient at times with oil—which is funny because the way I paint is so painstaking that it takes as long in oil or ink. But I do really like the immediacy with paper. My images became really distilled and spare. The negative space is so important to the work and the compositions, and conceptually the paper reinforces that. There’s no going back with ink, so every mark counts, and every bare space is there for a reason.

I like the connection to classic nature illustration. The connection is going to be made anyway since I’m doing nature on paper. Watercolor or ink on paper was always used in “recording” type of work, whether it was to depict a new species from a new land, or anything that needed to be captured and recorded. I think of my images as “recording” somehow, like recordings of something that I could have seen, or could have happened.

George Boorujy, Ram, courtesy of the artist

DK: I like that irony in your work. Here’s a medium used traditionally because it’s quick and yet your work is so meticulous and exacting. The viewer can’t help but notice the commitment and unusually close attention to the subjects. Can you talk about that highly realistic aspect? You’ve said that you are often criticized for rendering a subject near-photographically instead of simply taking a photograph. Roger White recently wrote a piece for “Modern Painters” about how realism continues to be marginalized in contemporary art criticism, despite the recent resurgence of figurative painting. What do you make of this ongoing suspicion around the issue of representation?

GB: It was more so in undergrad that I found myself defending representational art. One time in a crit someone brought the charge that my work was too “pretty.” That really doesn’t mean anything, although I know what he meant. I wasn’t making great work—I was 19 or 20. The work was technically good, but I wasn’t really saying all that much. But neither were the 20-year-olds who were working completely non-representationally. It was just easier for them to cover up inequities in the work and act like people maybe didn’t “get” what they were doing.

That being said, I really don’t like “show-offy” painters, work in which you see the craft and only the craft. I don’t see the point in a feat of mere technical proficiency. It’s like someone who has the best vocabulary, but never anything interesting to say. Then why not just take a photo? There actually are no photos of the stuff I draw so that’s not an option for me anyway. For most of the animals, and a lot of the buildings, I actually do make little sculptures and then draw from those.

Craft is tough. I love it, clearly, but I hate when it gets in the way. I want the viewer to see the image before they see how it was made.

DK: It seems as though the art world is still mired in an early to mid-20th century concern in this respect. Oddly enough, in the literary world, despite similar early fears that film would render the novel obsolete, for example, the debate has largely dissipated. I mean, the novel that is being touted as one of the most important literary works of our day is one of high realism: Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom.

GB: I think it might come down to communication. People in general are going to want to read a story, at least most of the time, not just a collection of words. And most people listen to music that has a beat, and rhythm, and melody. Visual art might be the same way. People like pictures of things. Sometimes I think people feign a bit of interest in really conceptual visual art so that they seem smarter. Believe me, some of the best work really is purely conceptual, but a lot of it is crap too. It’s just easier to ignore. How many people sit down and read a really experimental novel, or plug in their earbuds and turn on dissonant experimental noise? Occasionally, yes, but all the time? It’s easy to ignore crappy visual art because it’s not assaulting your ears. You can just turn away.

What I’m saying is that if you have something to say, it can be helpful to use an existing language—visual or otherwise—to communicate that idea.

DK: Can you address the surrealism in your work? I like the ambiguity you keep in play by gesturing both forward and backward in time. It’s also a strategy that helps keep any possible didacticism at bay.

GB: None of the buildings or landscapes that I draw exist. Nor have I seen a three-legged bear crouching over a seagull carcass, or a doe nursing a full grown buck. But I want all that to seem like something one could see. I want it all to seem plausible. Getting back to the craft thing for a second, that’s one of the reasons I render the way I do—to make it look real. I think the surreal aspect lies right in there. Things look real, or “witnessed,” but they’re off.

I try to keep my work, or the suggested narratives of my work, vague and up for interpretation. There’s a real environmental bent to my work, but what am I going to do, draw a picture of a crying bird covered in oil? I love oil! I depend on it, like we all do. I also eat animals. But I also consider myself a conservationist and environmentalist—whatever that actually means. What interests me is how we navigate and see this world we’re in, and the issues are complicated. We all know the tragedy of how we’re changing, or wrecking, our environment. There’s no need to spell out the disasters one by one.

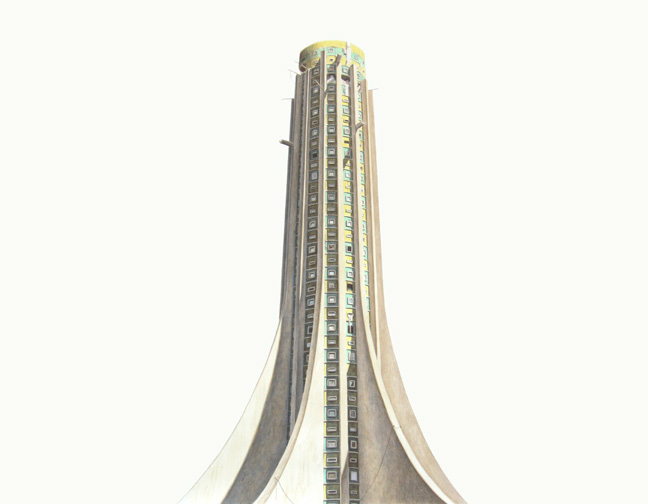

George Boorujy, Rubber Tree, 2008, ink on paper, 38 x 50 inches, courtesy of the artist

DK: Instead, those disasters are undertones everywhere. We don’t know the specifics, but there’s a sense of latent violence or imminence, especially in the landscapes. I am also thinking of the piece with the brutalist monument with the rubber tree gutters. Can you talk about the conflation of the natural world and the man-made in that piece?

GB: Well, it ties back into how we fit into our environment, and that includes what we build, how we mark the landscape, how we use and change materials, the forms our buildings take, what conventions of building become common, which are dictated by pure physical possibility. “Rubber Tree” (2008) was that pretty much in a nutshell. It’s about the Congo to a large degree, but more generally, about post-colonial Africa. The rubber industry built and destroyed the Congo. It’s a brutal industry. There was such optimism and excitement in the post-colonial era, but we know what has happened to the Congo since. I wanted the building to seem like something that was put up then, in the 60’s. There’s a building in Brazzaville that has a vaguely similar shape, but I wanted to make a tower that really looked like a tree, with the buttressed roots, etc… The gutters reflect the taps for the rubber. I wanted to then cut the building off bluntly and brutally as a reference to how they would occasionally chop the trees to get as much rubber as possible, not thinking of any sustainability. More importantly, it’s a reference to the chopping off of hands and other appendages which is an ongoing legacy that started during the colonial period.

Most of these ideas aren’t evident in the piece. But hopefully it looks like a somewhat strange, brutal building.

DK: Tell us about your new project involving pelagic birds. How is it a departure, if at all, from your other work?

GB: Here’s the basic gist: I’m putting original drawings of pelagic (open ocean) birds in bottles, along with a questionnaire, and launching them into New York waterways. I had wanted to do a project about the garbage gyres in the ocean, our connection, and obliviousness, to the ocean, and our impact on it. I decided on birds because I had to limit it somehow or else I’d be drawing diatoms until I was 80. Nothing better than charismatic megafauna! By nature of being pelagic, these birds occupy the largest surface area of the earth. Yet we hardly see them. Most people wouldn’t be able to name one, and even experts know very little about most of them.

I’ve also been very interested in the value of art, and what we value in general. We must value all our plastic goods—at least, we value the fact that they’re disposable, because we dedicate a lot of energy to producing and distributing them. Yet, once we dispose of them, they are considered trash. And as far as art goes, only a select group is able to afford art. I was interested in giving it away, equalizing that playing field, even if only in a tiny way. I was also interested in the question of what exactly I’m doing if I throw something that has market value in the ocean. Is it littering? If I threw a hundred dollar bill on the sidewalk, is that littering?

I assume most of these bottles and drawings will never be found. But then, in a way, when my work is sold, it too goes adrift and I don’t see it again.

]]>

Mike Leigh, Another Year, 2010. Via Overstreet on the Riviera

Ruth Sheen, who plays one-half of the well-loved older couple that is the focus of Mike Leigh’s latest film Another Year, is not beautiful. The unkind adjective for women like her—and by this, I mean, not unkindly, those who have aged naturally, allowing their skin and flesh to follow their intended gravitational course–may be “matronly.” Were she to be an actor in the U.S., and not England, I’d say the chances of her gracing the silver screen in a major role would be approximately zero.

But grace the screen she does, in all the best meanings of the word, in this deceptively simple portrait of middle-class life from the award-winning director of Happy-Go-Lucky, Vera Drake, and Secrets and Lies. With his new film, Leigh revisits the same temperamental dichotomy explored in Happy-Go-Lucky, deploying a similar strategy to achieve his particular brand of realism: pitting the well-adjusted against the miserable in a series of increasingly uncomfortable conversations. Like its predecessor, Another Year is a film that is driven by talk, and banal talk at that, but, as we have come to expect from Leigh’s work, it manages to rise far above what, in a lesser filmmaker’s hands, would be the severe limitations of rapid-fire platitudes (perhaps a byproduct of the improvisational method) and everyday circumstances.

As the title indicates, Another Year observes a year, demarcated by the four seasons, in the lives of North Londoners Gerri (Sheen), her husband Tom (Jim Broadbent), and their friends and family. Gerri, a counselor in a medical clinic, and Tom, a geological engineer, are that rare but pleasantly reassuring anomaly in cinema: a happily married couple. They live in a cozily decorated, quasi-bohemian home and are nearing retirement. They garden in all weather, cook, and enjoy their jobs. They also have a grown son, Joe (Oliver Maltman), who, perhaps following in his mother’s footsteps, works in a social service capacity, as a community lawyer.

Mike Leigh, Vera Drake, 2004. Via Public Radio

It is the couple’s friends—particularly, Mary, a secretary at Gerri’s clinic, and Ken, Tom’s childhood friend—for whom happiness is more elusive. Of the two, Mary, a self-conscious, middle-aged Miss Lonelyhearts, played by Lesley Manville, fondly orbits Gerri and Tom, coming over to their home often for dinners and barbeques, in the hope not only of enjoying their company but also of flirting with their son, almost twenty years her junior. She calls herself a “glass-half-full” person and says that she likes her life, but the fidgety, uncertain manner in which she rambles on about her car and man troubles suggests a deeper unhappiness to which she cannot yet admit.

The other friend Ken (Peter Wight)—bulky, neckless, and proud to sport a T-shirt that says, “Less thinking, more drinking”—does not live in London, so visits the couple less often, but when he does, is no less forthcoming with his lubricated expressions of personal woe. The first time we see him, he breaks into sobs after fifteen minutes of catching up with Gerri and Tom.

Is it class that doles out this disparity in happiness? Certainly, the stubborn resistance of the woman we first meet at Gerri’s clinic when the film begins—a stern, middle-aged, working-class woman (Imelda Staunton of Vera Drake) who complains of insomnia—feels familiar to us. Staunton’s character simply wants sleeping pills; she resents that her doctor and then Gerri imply a deeper, more psychological reason for her sleeplessness and try to help her by engaging her in talk therapy. When Gerri asks her to think of her happiest memory, she replies that she doesn’t know. Gerri pauses, rephrases the question, and asks her to take her time. Still the woman refuses to answer. When asked what would make her life better, the woman responds, “A different life.” Leigh directs this scene unflinchingly. Gerri is a paragon of respectfulness, grace, compassion. She carries herself with a stillness that should be the attribute of every good therapist, counselor, or psychiatrist. But the woman across her desk is no less empathetic in her stonewalling. We can understand her reluctance to share. Why should she air her dirty laundry? What could possibly be changed in a life of hardship and disappointment by telling a stranger how she feels? And who is this woman, this counselor, who lives a comfortable bourgeois life of contentment, to understand or help or make recommendations for improvement?

Mike Leigh, Another Year, 2010. Via The Independent

Unfortunately, we never see Staunton’s character again in the film. But we do, in a bleak English winter, quite appropriately, meet her male equivalent: Ronnie (David Bradley), Tom’s brother, who has just lost his wife Linda. Hull, where Tom and Ronnie grew up and where Ronnie still lives, is so grim, lifeless, and economically deprived that this segment of the story almost appears to be a different movie. The palette turns blue-gray, and Ronnie, gaunt and forbidding with the facial features of a hawk, looks about as mean as life has likely been to him. Ronnie’s life is the road Tom’s didn’t take, and his family—like Tom’s, with an only child, a trio—is as loveless and estranged as Tom’s is fulfilled, a fact made painfully evident by Linda’s sparsely attended funeral and the exchange of caustic words between father and grown son Carl, who arrives late and lashes out at everyone.

That Tom came from this milieu is significant, suggesting that social mobility in Britain is still possible. But what made it available to Tom and not to Ronnie? Inner talents, more self-determination, better social skills, luck? Leigh doesn’t provide us with enough exploration of the brothers’ pasts to come to any satisfactory answers, but if Ronnie’s impenetrable catatonia is any clue—it cannot all be shock and grief, Tom was always the brighter bulb of the two.

When Tom invites Ronnie to stay with him in London for a few days after the funeral, we feel almost physical relief that Ronnie will be removed, at least for a little while, from his sarcophagus of a council flat. But once there, Ronnie, like an errant bleach, subdues the formerly vivid colors of the couple’s home, and the dour hues of Hull return. By no ill will of his own, Ronnie changes the home from a place of warmth and welcome to one of caution and stinginess. We see this during an extended scene when Mary comes to the house looking for Gerri and Tom while they are out and Ronnie holds the front door open just the requisite amount of inches, trying to assess whether or not to let her in.

Mike Leigh, Happy-Go-Lucky, 2008. Via indiewire

Of all the troubled people in Another Year, though, it is Mary who receives the most attention; indeed, the film ends with a lingering close-up of her face at the kitchen table, as if to distinguish her from the others with a final question mark. Mary, unlike Ronnie and the insomnia patient, is not hopeless. She is not past feeling, and therefore, not past the point of change, in part because the main derailments in her life were a result of poor choices (for example, an affair with a married man), not a deck that was already stacked against her. In fact, it is vanity that keeps her from having a meaningful romantic relationship (she rebuffs Ken for Joe), and it is pride that motivates her to reject out of hand Gerri’s suggestion that she seek professional help from a therapist. At the end of the film, when she breaks down, her pathos is real. We have all been Mary in that moment, full of remorse, bereft of purpose. And we have all looked to those people in our lives whom loneliness and desperation never seem to touch and wondered, How? How did you do it, and why can’t I?

As upright and together as she is though, Gerri (and for that matter, Tom) is not annoying to watch (unlike Poppy of Happy-Go-Lucky whose ebullience tends to chafe). Nor does she smack of two-dimensionality or disingenuousness. She seems to have come by her good life and her goodness by acquisition of genuine wisdom and experience. For all intents and purposes, she is someone whom one ought to strive to be.

We do not often see characters like hers and Tom’s, perhaps because portraying virtue on screen is prone to flatness and thanklessness. Typically, if it is to be portrayed in film, it must be writ large and tragic-heroic, embodied by a likely or unlikely character who must struggle against an unjust society or circumstance (recently, Never Let Me Go, and less recently, the oeuvre of Lars von Trier). If that goodness doesn’t triumph, it is usually snuffed out, slowly and excruciatingly (The Bicycle Thief, Dancer in the Dark) or corrupted absolutely (Michael of The Godfather, Rosemary of Rosemary’s Baby). There is no such nihilism here. Instead Leigh’s minimalist realism seeks to capture only the most basic manifestations and contours of a good life. His scope is modest and his characters Rohmer-esque in their commonness, but the questions the film raises are absorbing, necessary, and instructive: How should a person be? How should one live this life? The answers, Leigh suggests, at least for some of us, may not have to be as difficult as we make them.

]]>