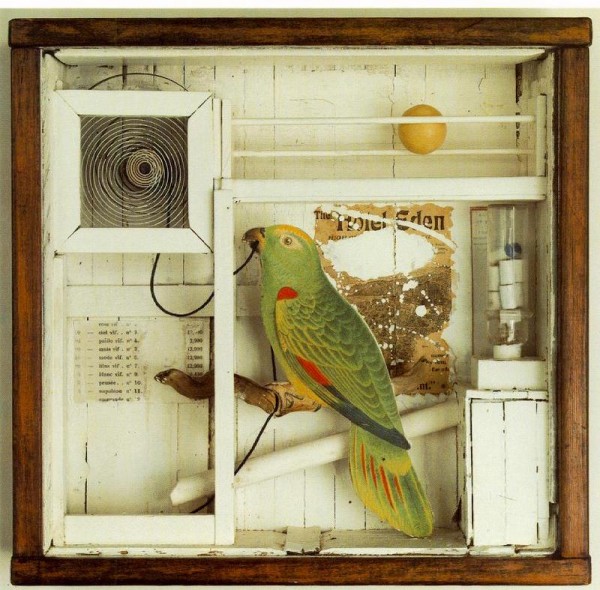

Joseph Cornell, Untitled (The Hotel Eden) c. 1945 via the Artchive

Dime-Store Alchemy, originally published in 1992, (and republished next week by NYRB Classics) is a collection of prose fragments tasked with the poetics of self-portraiture. It is a particularly monumental task given that its author, Charles Simic, is a Poet Laureate and the celebrated author of dozens of collections of poetry, half as many translations, and a handful of collections of prose. In the preface, Simic describes the collected fragments as an exploration and coming to terms with the working method of Joseph Cornell, a somewhat lesser-known participant in American surrealism who assembled disparate found objects in frames of his own making. Imitating Cornell’s method, Simic plays at a prose version of collecting and framing, shuffling moments in the life and work of the artist “until together they [compose] an image that [pleases] him” (x). Yet at its core, the collection chronicles the struggle between a popular poet and his complex historical inheritance. Simic, after all, is a Serbian import, and although he is a major fixture in the landscape of contemporary American poetry, his work is the product of an ongoing struggle to reconcile that identity with its Balkan, European, and American precedents. In Dime-Store Alchemy, Simic attempts this reconciliation in the unlikely figure of Cornell — not through a synthesis of historical traditions, but through an accumulation of fragments of their detritus. It is in the dime-store, where cheap novelty items and daily essentials sit side by side, their only commonality a five-cent price tag, that Simic makes his fragmentary acquisitions.

Joseph Cornell, who serves as the poet’s alter-ego, is himself a misplaced modernist. Unlike Simic, Cornell was born in the US; however, he participated in a thoroughly European avant-gardism. Surrealism was a French import, and the practice of assemblage and collage that pre-dated his working method was of European dada origins. Simic writes of Cornell as if he is on the periphery of multiple modernisms, constantly shifting between the burden of a Parisian modernist debt, the lonely hermeticism of a basement studio in Queens, and the crowded alienation of a 1930’s Manhattan street.

The first section and a half of fragments (that is, half the book) finds itself on the losing end of these struggles with periphery. The first section in particular, “Medici Slot Machine,” returns again and again to the milieu of Nineteenth Century Paris. Each of the obligatory touchstones is fondled: Poe’s “Man of the Crowd” is summarized in “The Romantic Movement,” Baudelaire speaks of the magic in the city in “A Force Illegible,” and the machine — that great beast of modernity — appears throughout (“The vending machine is a tattooed bride,” (28); “The machine, like any myth, has heterogeneous parts” (29); “The city is a huge machine” (30)). Even the prostitute makes an appearance (28). The whole of this section feels at home in a Benjamin-on-Baudelaire Paris Street, though one painted in broad strokes and populated by Cornell and Simic dressed as Flâneur and ragpicker.

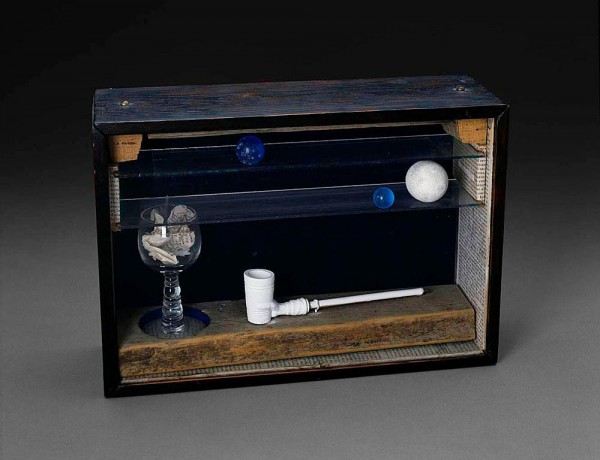

Joseph Cornell, Untitled Soap Bubble Set, 1948. Via Rocaille

Simic seems aware of the problem, but also wholly unequipped to solve it. For example, early in section two, titled “The Little Box,” the poet muses that an uninformed viewer of Cornell’s personal effects might take them to be “the strangest trash imaginable, for there are things in it that could have been discarded by a nineteenth-century Parisian as well as the twentieth-century American” (37). The poet, of course, might equally be that twentieth century American, and it is unclear why his garbage continues to look the way it does. Yet for all its nostalgia, the first section of the collection manages to bind the artist with the poet in appreciable ways. Simic describes Cornell as a realist, one who’s sorting, collecting, and framing of reality ultimately renders it surreal. Simic’s poetry, particularly in this volume, follows the same course. His fragments collect material from New York Streets and situate it in a series of nesting frames. In the poem “Medici Slot Machine,” for example, Simic writes of vending machines filled with mirrors that turn into reflective containers for a collection of “panhandlers, small-time hustlers, drunks, sailors on leave, [and] teen-aged whores loitering about” who then mix with “smells of frying oil, popcorn, and urine” (28). This poem, in turn, is framed by the entire section “Medici Slot Machine,” itself a container of both American surrealism and the version of modernity that looks like nineteenth century Paris. The framing thus expands to contain framing itself — the collectors, framers, collagers and assemblagers of European high modernity. And this is Simic’s gambit. It is the end-game of the collector; the final state of the curio cabinet—the world in miniature, rendered finally surreal. It is not a resolution, but rather a kind of coping strategy; once framed, these fragmented modernisms can be set aside. Simic offers his reader a short poem by Vasko Popa (a Serbian-born poet, like Simic, from whom he borrows the title of section two) to seal the deal:

The little box gets her first teeth

And her little length

Little width little emptiness

And all the rest she has

The little box continues growing

The cupboard that she was inside

Is now inside her

And she grows bigger bigger bigger

Now the room is inside her

And the house and the city and the earth

And the world she was in before

Now in the little box

You have the whole world in miniature

You can easily put it in a pocket

Easily steal it easily lose it

Take care of the little box.

It is only after the little box is taken care of and put on the shelf — after the struggle with irreconcilable modernisms is put into its own frame to be observed – that Simic’s sympathies for Cornell subside and true homage can take its place. The result is an uncritical return to the stirring verse for which Simic is best known. A somewhat indulgent celebration of the mystical effects of juxtaposing unrelated words, images, and objects ensues — Simic’s take on the magic of assemblage. This happens right before the third section of the book, “Imaginary Hotels,” wherein Simic explores the impossible themes of beauty, art, imagination, and death. And I don’t mind it at all. The poet makes the transition as if no alternative is possible (which may be true). Nothing is resolved, but everything becomes allowable. A necessity, it would seem, for wonderful passages like this:

]]>“Blue is the color of your yellow hair,” said Schwitters. He walked into a forest near Hanover and found there half of a toy train engine, which he then used in one of his collages.

Beauty is about the improbable coming true suddenly. The great ballerina, Emma Livry, a protégée of Taglioni, for instance, died in flames while dancing the role of a night butterfly.

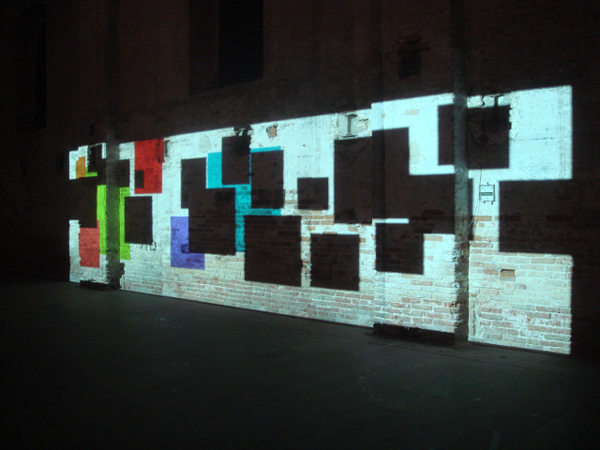

Alban Muja & Yil Citaku, Blue Wall, Red Door, 2009. via Alban Muja

I met Alban Muja back in 2006 while on a trip in Albania and Kosovo researching a fledgling exhibition. That show never really came together, but the research led me to some terrific artists working in and around issues of everyday political aesthetics in ways that are foreclosed for contemporary New York video. These artists are part of a generation of Albanians for whom successful art making is marked by absence. The slightly relaxed borders of their own countries and the new ease of movement within the EU meant that successes from past generations like Albanian Anri Sala and Serbian Marina Abramović could more easily integrate into a global community of artists. This had the effect of opening Albania and Kosovo to an imagined international community, but it also meant that the local art scene became drained of influential practitioners. For the younger generation of artists making art became inextricable from issues of movement and international identity, and Alban Muja was one of those artists.

Currently an artist in residence at UnionDocs through CECArtslink, Muja has organized his work to date loosely around themes of movement, naming, and territory. It is an unsurprising gesture, perhaps, for an artist born in Kosovo, a contested political no place with an ambiguous identity, impermeable borders, and a recent history of ethnic cleansing. What is surprising, however, is that Muja locates these themes in the personal and private lives of his subjects to the degree that the political and historical are rendered distant or even obscure. For Palestina for example, Muja interviewed an Albanian girl whose mother named her “Palestine” after hearing a news story about the tragic death of a young Palestinian couple. The interview does not dwell on the overtly political, focusing instead on what it is like to have such a strange name, what it means to be proud of a name, and what happens to a subject’s identity when she is named after people and places she knows very little about. Similarly, Tibet is the story of a Kosovar Albanian living in Switzerland who was named after the Chinese territory. In each of these videos naming and the lived experience of bearing a name become intimate activities rife with pride, indifference, identification, miss-identification, and even violence.

Alban Muja, Tibet, 2009. via Alban Muja

Other works by Muja struggle to find orientation and place in both the everyday and the artistic. For Blue Wall, Red Door the artist investigates the way that Kosovars navigate their towns. Citing the lack of consistency in street names, the video explores how notions of location and direction do not translate exactly in a place like Kosovo. Where locals orient themselves based on known locations and landmarks, any visitor attempting to navigate Kosovar towns will find maps and addresses useless. Conversely, Free Your Mind is the artist’s attempt at navigating the territory of art history. As a young video artist working in a country where “video art” does not exist, the lessons and inspiration of western art history become a hindrance rather than a map for art making. Muja recites as many names as he can remember in an effort to eliminate them from his mind and proceed with his own process—but of course the names pile up, becoming the work itself, in the end.

This Sunday at 7:30 pm Alban will be screening these works at UnionDocs in Brooklyn and will entertain questions afterward from curator Eriola Pira and me. If you are around please join us for the discussion.

]]>

Paul Chan, Sade for Sade

Visitors to Paul Chan’s Sade for Sade’s Sake, the artist’s second solo show at Greene Naftali (on view October 22-December 5) may recognize his latest projected work as a continuation of his exploration of light and shadow in the vein of the 2005-2007 7 Lights. The enormous 5 hour, 45 minute projection at the center of the show features digitally-rendered figures and forms inhabiting a richly-colored, shifting ambient space reminiscent of the projections exhibited in 2007 and 2008 at the Serpentine Gallery and New Museum. Like the Lights, which shared the museum floor with black and white studies and music scores, Sade shares the exhibition space with black and white works on paper. However the obvious connections to Chan’s earlier work end there. In contradistinction to his subtle, if haunting, 7 Lights, Sade for Sade’s Sake is jarring in its explicit sexuality. Visitors entering the gallery will get a hint of this licentious aesthetic as they walk past a small room of Chan’s line drawings (more on these soon) to make their way to the projected work. But whatever minor acclimatization these drawings offer, the effect of the projected bodies in Chan’s Sade is still arresting. Nearly life-size shadow figures stretch across the gallery’s back wall convulsing and gyrating in a state of orgiastic trance. The gamut of sexual encounter and style is depicted—masturbation, oral sex, bondage, straight sex, gay sex, three-ways, four-ways, rear entry, reverse cowgirl, and what looks it might be pedophilia. However at no point in the course of the projection is it clear if these bodies are engaged in a celebration of sexual liberation or a torturous sexual assault. Their movement oscillates between rhythmic thrusting and psychotic convulsion as they appear standing, sitting, suspended from the ceiling, kneeling on the floor, writhing in groups and shuddering alone.

Sade for Sade’s Sake is projected onto the gallery’s entire north wall, a large rectangular surface broken by radiators, columns, and painted-over windows. In combination, the projected images and architectural elements suggest an interior space similar to a prison cell or dungeon. Appropriate, of course, because this new body of work takes the writing of the Marquis de Sade as its starting point, in particular 120 Days of Sodom (for reference the 7 Lights were loosely based on the 7 days of creation in the Judeo-Christian tradition). For Chan as for de Sade the prison cell and the sex dungeon are one and the same. A simultaneous critique and celebration of libertine sexuality is imminently readable in the work, as images of what could be sexual indulgence or violence, transgression or punishment, repeatedly form and dissolve. But despite its explicit and jarring sexual content, Sade for Sade’s Sake is an extremely slow, contemplative work. Like the 7 Lights, it does not allow an instantaneous viewing—a fact underscored by the nearly 6 hours it takes for the full arc of the projection to unfold. Throughout this time blocks of shadow and light, like opaque windows, appear in the space of the figures. They change color and slide, slowly, across the wall, offering a steady visual reprieve from the figures’ erratic movements. Toward the end of the video cycle the shadow bodies begin to break down. Still thrusting and convulsing, they start to disintegrate, flickering into their smallest recognizable parts—arms, legs, torsos, penises. Now voided of both the violent and the erotic, these constituent parts act like sexual graphemes, the basic elements of a visual language in which images of both depraved sexual violence and overwhelming carnal ecstasy can be written.

The linguistic qualities of these disembodied parts are reflected in the gallery’s third room, where rectangular, human-high ink drawings of alphabets and sexually explicit phrases are propped against the walls. These towering ink works, which seem at first like sketches for a perverted ABC book or a Sadian Rosetta stone, are in fact translations of a series of fonts that Chan has made available on his website. Each of these graphic font tables is fixed to a pair of men’s or women’s shoes, and standing in the small exhibition space as tall as the gallery visitors, they appear like a language embodied. The lexical tables surround a single computer keyboard for which the regular keys have been replaced by miniature grave markers. A USB cord runs from the keyboard to a computer in the gallery’s front office, hinting that the keyboard could be used to transmit coded, erotic messages to the gallery staff. Unfortunately the keyboard is not actually connected, and the usb cable is more of a conceptual devise. In order to test Chan’s fonts, visitors must use the more orthodox keyboard plugged into the designated computer in the gallery’s front office.

Finally, the last major element in Chan’s show is a series of black ink line drawings. Like the rest of Sade, most of these works on paper are sexually explicit. They depict figures engaged in various sex acts or naked and striking revealing poses. In concert with the slow, almost graceful blocks from the projections, the elegant black lines of these drawings offer a foil to the jarring sexual imagery they depict. Moving from one drawing to the next the lines start to expand over the paper, taking over completely in some cases, and giving the effect of a wholly abstract, almost Brice Marden-esque composition. The line drawings, again, like the projection they accompany, navigate the divide between the erotic and the violent, however in their case this oscillation is perhaps more overtly political. The limp bodies Chan draws piled on top of each other bear a striking resemblance to the American soldiers’ souvenir photographs taken at Abu Ghraib. Likewise, Chan’s contorted, naked figures seem to be posed in “stress positions” reminiscent of the torture techniques used at Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay. In this way the lines that shift between figurative and abstract also shift from aesthetic to political. It’s a line that Chan navigates gracefully throughout his work, and can be found again in the 21 fonts he developed as part of Sade.

A visit to Chan’s website, which I recommend doing before visiting the show, reveals that not all of the fonts are composed in the voice of Sade’s characters. Though some have titles like Oh Justine and Oh Bishop X, obvious references to Sade’s work, others, like Junior George and Oh Monica, hint at characters from our recent political past. The Clinton/Lewinsky sex acts described in detail in the Star report and the piles of naked bodies in the Abu Ghraib prison photos are written here in the language of Sade. But more than that, Chan’s reduction of sexual excess and violence to basic units of written and visual language runs parallel to the sexual indulgence and violence that constitute the basic elements of contemporary American political/cultural discourse. The shorthand terms “Lewinsky” and “Abu Ghraib” point to the abstraction that high profile cases of sexual indulgence or violence undergo as they become the subtext of the political everyday. In turn, the nightly news broadcasts and family dinner conversations composed in this sexually-loaded shorthand become explicit, indulgent, and violent in their own right. This Sade-itization of the banal is reiterated one last time in Sade in the salacious monologues that the gallery staff will endure daily for the duration of the show. Benign greetings like “hi there” will be translated to “yes yes oh god oh shit yes yes yes hit that yes” (in Oh Juliette), as visitors test out Chan’s fonts on the gallery office computer.

Sade for Sade’s Sake is a significant moment in Paul Chan’s work to date and a considerable follow up to his much-loved Lights. Despite whatever distinctions Chan draws between his political and artistic interventions, Sade offers a complex, endlessly shifting engagement with the erotic and the violent, the banal and the political, the figurative and the abstract. That being said, the political moment that seems most proper to this work has expired—this is no longer the era of Lewinsky-gate or W’s administration. Today the stakes of “sexual transgression” and mediation in the public sphere are more firmly rooted in questions of gay marriage and the legal status of consensual sexual relationships. Given the recent failures of state-level gay marriage referenda, I wonder how, if at all, the line that Chan’s Sade navigates has shifted. Certainly Chan’s interest here lies in the intersection of legal systems, language systems, and sexual practice. These terms collide in the gay marriage debate, which is of course not absent from Chan’s show, but is certainly a more subtle character than Abu Ghraib or Monica Lewinsky.

]]>