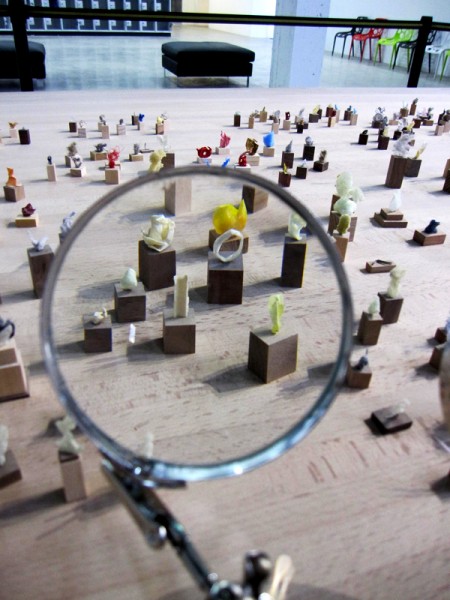

Benoit Pype's 'Fabrique du résiduel.' Photo by Benjamin Evans.

The contemporary Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben has recently drawn attention to the insistence by most philosophers that art be approached from a position of disinterest, as it generally has been since at least the time of Kant. This intellectual preoccupation with the idea of a neutral position for approaching art has resulted, according to Agamben, in an artworld that is not only disconnected from the social and political sphere, but also to some extent one which even celebrates this disconnection and glories in art’s “autonomy.”

The work on view at Intense Proximity, the 2012 Paris Triennale, might initially be seen as an attempt to address this situation. It brings together the work of several generations of artists from all over the globe, all working in diverse media and contexts. Almost all of them share a concern for connecting their work to broader social or ethnographical issues. The exhibition is intended to blur lines between artistic and ethnographic investigation, and rather than address, in the words of its curators, questions of “how we might share a common space or live together,” it aims to address “the more salient question of how to live with disjunction.” At some level, the exhibition is overtly an attempt to engage in issues of broader public concern, to engage in an interested art.

Yet — much of the structure of this massive exhibition contradicts this apparent concern. First of all, I’d like to ask: “who is the audience of this exhibition?” The obvious answer, given that it is held at a huge public art gallery is: The General Public. In particular, the public who live in a world of mixed cultures growing increasingly close to one another.

The sheer size of the exhibition argues against this simple answer. Even if one ignores the six other venues and concentrates just on the central core of the exhibition at the eye-boggling new Palais de Tokyo space, there is an enormous amount of work to be considered. Furthermore, this is not simple work meant to delight the senses with aesthetic pleasures, but work that requires thought, interpretation, and investigation — work that demands that the viewer take time. Supposing one gave each of the 113 artists ten minutes each, it would take almost nineteen hours to see the show (perhaps three six hour days?). Of course, much of the video-based work demands much longer than ten minutes — the combined total video is over 729 minutes (over twelve solid hours). What members of “the general public” could be expected to invest this sort of time and energy?

This sort of criticism might seem silly — nobody goes to a gallery with a stopwatch and gives ten minutes to each artist, and nobody watches all the video. Especially at gargantuan spaces like this one, people wander around looking vaguely at different things, approaching and dwelling on individual works or installations that catch their eye. The assorted artworks all compete for attention, and generally the ones with more obvious punchlines, more graphic content, or more easily digested material win a slightly prolonged gaze. For most people the goal is to “complete” the exhibition in a reasonable time frame (say, three hours?). They only concentrate on a few well chosen works.

If such is the case, does it make sense to present so much demanding work in the same place at the same time? The inevitable result is that I am forced to make a choice. Either I do my best to respond with the concentration and respect demanded by each work, or I must be selective and walk blithely past works that call out not to be ignored. Given the political stakes involved, I am caught in a serious challenge: ignoring work about slavery, warfare, revolution, exclusion, death, and otherness is itself a political act. Yet the curators seem to leave me with little choice. The context forces viewers to trivialize the complex politics at stake by asking us to browse a Wal-Mart of issues.

This isn’t simply a matter of quantity, but also one of quality, of the varied and demanding contents involved. Another contemporary philosopher, Jean-Luc Marion1 is relevant here. In his thinking about television, Marion argues that we are phenomenologically unequipped to experience the world presented by television. In the act of watching TV, we might jump from a golf game to a documentary about ancient Rome to The Simpsons to a cake-decorating competition to news about a conflict zone in the Middle East to numbers from the stock market. This constant jumping geographically and temporally renders the world effectively uninhabitable by creatures built the way we are — we just don’t have the equipment to apprehend (let alone comprehend) such a place. Similarly, Intense Proximity bombards the sensitive viewer with material of such ethnographic diversity that they cannot possibly process it all. Bewilderment is the only response. Perhaps this is an important result in itself, to throw a wrench into any simple why-can’t-we-all-just-get-along attitude. But as it poses no alternative response, I’m unfortunately left feeling disempowered, that ignorance is indeed bliss.

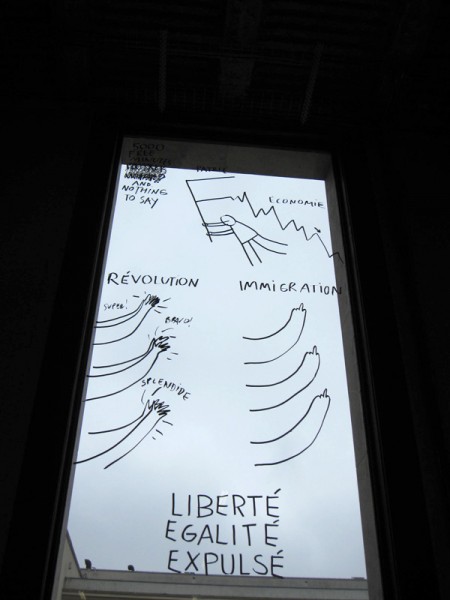

Dan Perjovschi. Photo by Benjamin Evans.

There is further evidence that the General Public is not the intended audience for this show. Frazzled by the rather daunting task of having to assimilate (or at any rate experience) so much divergent material, and challenged by the unfamiliarity of much of the work on display, a determined visitor might turn to the ten-euro “exhibition guide” for assistance in understanding and contextualizing his/her experience. Here, however, one encounters sentences like,

“Every curatorial process begins its appointment with these contending positions, particularly in the midst of epistemological uncertainty and cartographic instability that governs not only the production of art, but also the circulation of signs.”

and,

“We wanted to construct the project topoi as a field of contending discourses.”

These are sentences addressed to people who have read Foucault, Lyotard, Barthes and, perhaps, even Derrida. Is it reasonable to assume that the General Public (even the French general public) is familiar with the cartographic instability that governs the production of art, or even know what project topoi might be?

This kind of language renders the author a specialist, much the same as physicists who effortlessly use words like superposition states and scalar bosons. Physicists are expected to know these terms, but are not expected to discuss them with a general public very frequently. To be clear: I’m fine with the idea of artists (or philosophers) having their own specialized, expert vocabulary, as some of the questions involved in such subjects are just as complicated as particle physics (viz. Kant). In my line of work, it is sometimes useful to have terms like epiphenomenalism, aporia, or possibly even Dasein. But if the goal is to interact with the general public, this kind of language is downright irresponsible: it simply alienates the intended audience, communicating only a message of intellectual difference. This show takes place in a public space, with an explicit concern for matters concerning the public sphere (living with disjunction, cultural representations, etc). It is a show about culture, politics, and people. How then can the curators justify leaving so many people behind?

The conclusion is that the show is not actually for the general public, but for a small minority group concerned with contemporary art. This is revealed implicitly in the manner described above, and also revealed explicitly in their text. The curators themselves state that they are concerned with

which artistic positions gain preeminence and which, therefore, possess the requisite access into the forest of signs that define the landscape of contemporary art in the era of neo-liberal capitalism.

In simpler words, they’re interested in the artworld, and who gets to have a voice within its complex structures of power. Certainly the ongoing project of dismantling the white, western, male paradigm of the artworld has merit. Yet if this is the case, it appears we are right back where we began: with Agamben’s apparently justified concern about an artworld that seems only to care about itself, deliberately and gloriously autonomous from any broader public concerns. Again, I must ask: If one is genuinely concerned with the politics of multicultural disjunction, why target the tiny and generally ineffectual cultural group that takes in interest in contemporary art2 ? Why not try to engage with the General Public?

I realize some of my remarks on public accessibility might seem applicable to any large blockbuster show, and that any number of spaces (including my own) could be criticized for the use of elitist “expert” vocabulary. Yet I insist: this show is particularly open to these charges because of the contradiction between what it claims to attempt, and what it achieves. If an elitist gallery wants to use highly specialised language to sell expensive objects, I have no objection (or rather, my objections are entirely different and much weaker). But to raise complex issues of identity and representation, relevant to pretty much everyone on earth, you cannot open an elitist shopping mall of ideas advertised with jargon. It is like making a Disneyland ride about world poverty: the format contradicts the message.

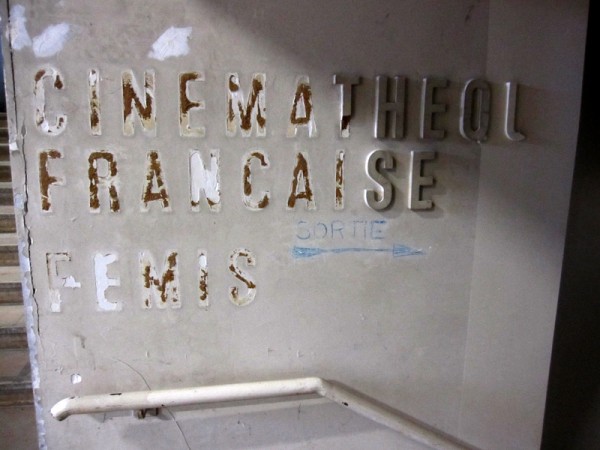

Photo by Benjamin Evans.

Still, it might be said that these remarks concern general curatorial strategies, rather than the work itself. In this show, however, curatorial decisions are almost impossible to ignore. Standing at the entrance to the Gallery Basse (the dark space in the lowest basement) I was able to hear competing audio from five video projections. Arab dance music (Hassan Khan) vied with a Roma street-musician (Alfredo Jarr) while an apartment building collapses behind it all (Bertille Bak). Singularly: worthwhile. In such Intense Proximity: aggravating.

The feeling reached such a point, that one of my fellow visitors couldn’t take it anymore and went to explore the fruit and vegetable market outside. A summary of her comments: “This is awful, I can’t look at this. So much death and war and crime and pain…It’s so aggressive!” Being in a basement with no discernible exits, with walls painted black and lights down low certainly didn’t help alleviate the sense of claustrophobia and panic. There is, of course, a noble tradition in art of attempting to shake bourgeois consciousness from its slumber by presenting it with material it doesn’t much want to see, but in this context the result is not progressive dialogue but despair.

My companion was right: there is a lot of death represented here, a great many photographs, videos, and installations making use of corpses for artistic ends (Closky, Delahaye, Jarr, Hirschorn, Sarkis, Toguo). Additionally, African masks appear with considerable frequency (Evans, Weems, O’Grady, Sarkis, Adeagbo), mixed with images of American political power (Jarr), disco dancing (Piper), watermelon seeds (Cannel), prostitutes (Moulène), and slaves (Weems). And of course you can buy a Rikrit shirt at the Gavin Brown shirt factory. If you want difficult issues, here you can find them by the pound.

Even so, from this swirling melancholy din, moments of art still managed to happen. Annette Messager’s empty but mysterious creatures floating around on currents of air strangely provided both relief and hope. Dan Perjovschi’s simple window graffiti cleanly, clearly, and unpretentiously poked at issues buzzing in the contemporary buzzworld. I was very pleased to come across a boring pile of sheets next to the name Jason Dodge. Mystified, I obediently read the description in my guide, and then meditated on the thousands of people who have slept on those sheets (they are replaced weekly by a hotel laundry service). I thought Jewyo Rhi’s Wall to Talk was brilliant — a low-tech creation of giant typewriter arms with home-made word stamps rather than letters, here narrating a disjointed but familiar text:offered the beaten taxi driver, big black man, police asked, Thinking of his blooded face. Mihut Boscu’s strange video installation appeals to me, dealing as it does with the history of corpuscularianism and fantasy science. It is also pretty hard to argue with David Hammons ’ Rock Heads work: smart, aesthetic, ingenious, simple, politically charged and understated. Bertille Bak, a young French artist, documented a song of protest being played by pulses of light from the windows of a condemned Thai apartment block, resulting in a poetic but powerful installation.

Cecile Beau. Photo by Benjamin Evans.

Don’t get me wrong: there is some good work here. My best in show goes to a young artist not even included in the Trienniale, but on display as part of the Modules — Fondation Pierre Bergé — Yves Saint Laurent program. Winner of the Prix Découverte des Amis du Palais de Tokyo, Cécile Beau’s Subfaciem included a seamless tree growing both upwards and downwards, and stalactites and stalagmites made from refrigeration systems. Benoit Pype, another young artist in this program, has taken over an immense space on the main floor for the fabrication of his miniature dust-sculptures, using it as a studio while the public peer curiously at his tiny work through magnifying glasses. Both are poets in the larger sense of the term, and in my view remind us of what art does best.

Likely a great deal of the work in this show, including the most graphic (Hirschorn) or most difficult (Weems?) would make a much stronger impact if shown in a more respectful context. As I look through the gallery guide and read some of the descriptions of the work3 , I see much that looks interesting, that calls for investigation up close, and it is unfortunate that I missed these in my two separate visits. Given the context, such invisibility seems inevitable. Perhaps the reader is best advised to just pick up the catalog and read for a few hours. Such is the fate of art in the age of the political theme-park show.

Finally: I could have filled this entire essay talking about the utterly bizarre new Palais de Tokyo space. (To give you an idea of the strangeness, another comment from my companion: “I feel like I’m in Sarajevo during the war”). But given that I can’t get into detail, let me just say that I disagreed with my companion. This awesome new playground and its abandoned factory aesthetic makes the price of multiple admissions worthwhile, whatever the status of its contents.

— April, 2012

- See The Blind at Shiloh in “The Crossing of the Visible”, James Smith Tr, Stanford University Press 2003

- This is not a pot-shot at the denizens of the artworld. The people who are interested in hot-rods, model trains, fashion magazines or hockey are also pretty ineffectual insofar as those interests go.

- and to be fair, many of these descriptions are in much better prose than the main essay

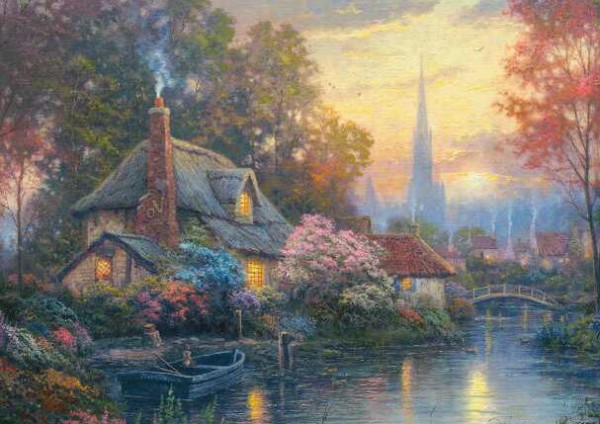

Thomas Kinkade's "Nanette's Cottage," courtesy of the artist's estate

Somewhere on the list of my top five art experiences is my first encounter with a “genuine” Thomas Kinkade. Like the first time I stood face to face with a Cezanne or a Basquiat (two other painters who have acquired a certain importance for me), the event had a surreal monumentality about it. For obscure reasons which I needn’t get into, one pre-Christmas not long ago I found myself wandering somewhat aimlessly in the Staten Island Mall. Unbeknownst to me, this was one of the select locations of an official Thomas Kinkade outlet. I immediately rushed in, enchanted and mesmerized. I knew the work, I knew his popularity among the general public, but somehow I had never been informed that the man owned his own retail outlets in malls across America. I must have been wearing a clean shirt, for the earnest sales clerk immediately identified me as something other than a regular looky-loo and approached me with a disarming smile as my head spun with the sheer vastness of Kinkade’s oeuvre. Calendars, prints, and posters, all displaying a bewildering variety of glowing cottages in all four seasons radiated in intense rainbow-pride color from every wall. Rendered defenseless by the opulence, the inconceivability of my surroundings, the besuited salesman easily led me to a kind of booth, a short hallway nook, all the while muttering what I took to be mystical incantations but were likely just bullet points from a brochure.

At the end of the nook was a painting, another cottage ready to explode with coziness beneath a gentle haze of woodsmoke. I heard something about a “recent innovation in painting technology”, and as the fellow manipulated a slider control on the wall, the lights in the booth dimmed, and before my very eyes the painting became darker and previously invisible stars began to glow in the sky. Against this descending wintry darkness no human soul could resist the impulse to make a dash for the cottage, to rush indoors and stroke a cat in front of a fireplace under a blanky with a mug of cocoa. An innovation in painting technology indeed!

I don’t know how I got out of the cottage and back into the mall. I just remember waking up at the food court having purchased a hot chocolate and checking to see if my wallet (and kidney) was still there.

Kinkade has always held an important place in my thinking about art, for several reasons. As has been noted in most of his obituaries, the “real art” world generally reviled Kinkade and his easy-cheesy sentimentality. As an artist, such easy dismissals are fine by me. Just as a fan of opera has no real obligation to consider the performances of a Britney Spears or a Shania Twain, neither does someone interested in, say, Rachel Whiteread or Neo Rausch have much obligation to pay attention to Kinkade (and of course, vice versa). As an artist, I have always thought that the dominance of this monolithic overarching concept of “art” is one of the most significant problems for artists today, and that we’d all benefit from following the example of the music-world with its obsessive but energizing categorization. But as a philosopher, or as someone who wants to think broadly about art and aesthetics, I do have an obligation to at least acknowledge the diversity of my field of interest. Thinkers about visual art have to face a phenomenon that includes not only canonical celebrities from Cezanne to Warhol, but also the Henry Dargers, Robert Batemens and Painters of Light.

Doing so, however, is difficult. Though debatable, let’s assume for now that all the recently lauded statistics are right, that Kinkade sold 100K worth of paintings per year, that 1 in 20 homes contains a work, and so on. Statistically he is the best selling painter ever to walk the planet. Jerry Saltz has (wisely) pointed out that sales figures are not a very interesting vector for evaluating an artist’s value1, but the point remains that his work (and its countless imitations) are extraordinarily popular, and demonstrate in an unequivocal manner just how undemocratic the structure of the “real” art world is. This observation itself may be something of a cliché by now, but I’m frequently staggered by how many young artists I meet feel that by practicing art they are associated not with an elitist, intellectual, aristocratic marketplace, but with a sort of grassroots populist movement, many of whom would agree wholeheartedly with Kinkade’s simple approach of art as an “inspirational tool.”

So the question is how to get Kinkade out of the picture, how to justify his dismissal. Saltz, in a very recent article2 that also acknowledges the “thought problem” generated by Kinkade, suggests quite simply that he is dismissed because of his total lack of originality:

Not one…of his ideas about subject-matter, surface, color, composition, touch, scale, form or skill is remotely original +

But I think we’ll have to do better than that. Surely Kinkade takes unoriginality to breathtakingly original heights? If cliché was fat, Kinkade’s cottage paintings would be the equivalent of deep fried bacon burgers floating in a warm butter soup. They’re just so unbelievably over the top, so pornographic in their banality — for my money they’re much closer to Koons Made in Heaven series than Norman Rockwell illustrations. They’re extensions of the great Komar and Melamid project that generated oil paintings based on surveys conducted by professional pollsters to determine the artistic preferences of different countries.3 Kinkade, without the aid of surveys, just tapped into an idea of what people like and proceeded to systematically generate dump-truck loads of it. Moreover, arguably this whole production was conceived of as a kind of deliberate critique. Fed up with the elitism of the art world in which he was trained, he responded with a very specific and intense rejection. A picture of a lovely little village at sunset is (paradoxically) a great fuck you to the theory-heavy debates of the 90’s art world, and the inevitable result of following a particular line of thinking to its logical conclusion.

One could also argue that Kinkade out-Warhols Warhol and beats Koons at his own game. With Warhol, for example, there were always overt statements, claims that it was all about money and fame, but these claims were frequently treated by apologists as cover for genuine occult or critical concerns. With Kinkade, his cover is so good we have no cause to suspect him of anything else (except, perhaps, during his occasional lapses into alcohol-induced escapades and pooh-bear urinations, which make him sound like just another Bushwick hipster on any given Sunday). It is not without some reason that Kinkade described himself as “the world’s most controversial artist.” For crying out loud — the guy designed entire subdivisions in which people actually live. By this standard, Koons has a long, long way to go.

Saltz writes:

The reason the art world doesn’t love Kinkade isn’t that it hates love, life, goodness or God. We may be silly or soulless or whatever, but we don’t automatically hate things with faith and love or that other people love. We’re not sociopaths. (Well, most of us aren’t) +

But the trouble is (as Saltz’s caveat hints), most of us sort of are sociopaths. If nothing else, Kinkade reminds us, or at least many of us, that we don’t like things that are popular, mostly because they are popular. We hold on to the notion, with increasingly stiff fingers, that art must be oppositional, confrontational to what is popular, and Kinkade makes this delightful bit of ideology (for that is what it is) clearly visible for us. This is not to say that there is anything wrong with being oppositional per se (surely there is a very great deal that is popular that does need opposing), but just to point out that rendering invisible ideology visible is itself a worthy project, and one that better respected artists have tried and failed to achieve. If we consider how previous avant-garde fuck yous have been reified and disarmed to become status symbols for the wealthy, we would do well to consider the challenge posed by Kinkade a little more deeply, even if it is partially a posthumous challenge presented by others.

A coda: Kinkade suggests that when people put his paintings on their walls, they are putting their values on the walls too. And that is likely true of me too: I put Siobhan McBride4 paintings on the wall, and that reflects my valuing of mystery, fatigue, ennui, discomfort, escape, release, life, and hope. Kinkade is a painter of light, McBride a painter of shadows. My preference is a reflection of deeper forces at work, forces of socialization as well as perhaps something deeper, at a more obscure part of my human being. Kinkade, in what is for me an experience of almost unforgivable badness, nevertheless reveals this deeply aesthetic core of myself almost as powerfully, if perhaps less pleasantly, than McBride’s more nuanced gouaches. Kinkade’s work reflects for me an “other” that I can never be but must only imagine: sitting inside the cottage, warm and toasty with a cup of tea in front of the fireplace, while I stand outside in the art world, in the mall, in my complex shadow, watching the glow-in-the-dark starlight emerge.

— April 15, 2012, Paris

- Jerry Saltz on ArtNet here, or originally on New York Magazine‘s Vulture blog here

- Ibid

- Likely the best place to review this project is through the DIA website and on their own site

- Siobhan McBride’s website

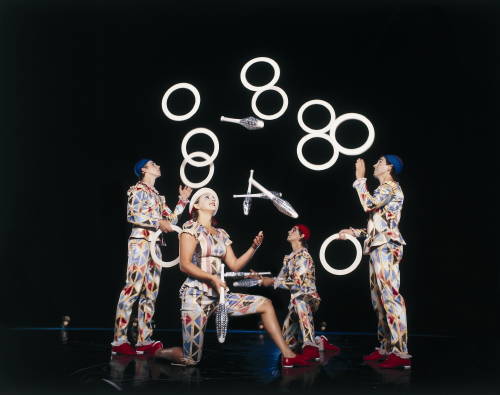

Le Cirque Invisible, via

Anyone who has been to the circus within the last decade or so does not have to be told that things have changed considerably since the days of the traditional big top. High-wire acts, jugglers, tumblers, trapeze artists, and clowns might still be there, but the contexts of their performances have changed enormously. Since moving to Paris a year ago, I’ve been fortunate enough to witness four performances that fall under this expanding rubric of “contemporary circus.” Without exception, they have been powerful, fascinating, and at times very moving.

The best known contemporary circus is unquestionably Cirque du Soleil, the group generally credited with inspiring most of the form’s innovations over the last twenty years. Its enormous reputation is entirely deserved. Its production, Corteo, which concluded its Paris run at the end of December, is emblematic of everything contemporary circus can be. Traditional acts (tumblers, stilt-walkers, jugglers, and so forth) follow each other in sequence, but here they are threaded together in a loose and poetic narrative, in this case the antic funeral of a clown, cortéo being the Italian word for cortège. The staggering difficulty of the acrobatic feats can almost get lost in the lavish costuming and swirling set-changes. The scale is nothing short of epic, and the emphasis is clearly on poetics and the elaborate construction of fantasy.

At the same time, particularly in the self-reflexive Corteo (which is, after all, a circus about a circus), Cirque du Soleil’s sustained theatricality maintains the basic tradition of the circus. Other instantiations of contemporary circus stretch the boundaries of the concept even farther, into genuinely interdisciplinary and uncategorizable territory. Au Revoir Paraplue, the phantasmagoric creation of James Thierrée, is neither dance nor theatre nor performance art nor circus nor concert, yet somehow it is all of the above. While considerably less grand in scale than Corteo (there are only five performers), the presentation is arguably more poetic, with less concern for presenting established circus tropes. Very (very) loosely based on the myth of Orpheus, it presents the narrative of descent into a mysterious underworld in which constant transmogrifications of people, places and things are the norm. Surrealist juxtapositions abound as the work nimbly leaps from tragedy to slapstick to something beyond such simple terms, an expression of pure delight in creativity itself. Here, the performers are not specialists in juggling or ring-spinning, but rather generalists of movement whose bodies appear to lack joints altogether. The entire purpose isn’t the celebration of physical dexterity, but the physical realization of unbounded imagination.

However, not all contemporary circus follows these lines of poetic extravaganza. The Russian clown family known as Semianyki, while still wildly creative, is more interested in fun, madness and anarchy than in poetic adventures in the underworld. The world of Semianyki (which I visited in May at the fantastic Théâtre du Rond-Point) is a clown version of the stereotypical, Simpsons-esque family: a deadbeat dad, a perpetually pregnant and authoritarian mom, two daughters (nerd and goth), a manic maniac son, and a cute but chaosophilic baby. The tradition of clowning has a rich and complex history quite apart from the circus, and while one might interpret Semianyki’s pantomime mayhem as social critique, the vibe is Tim Burton, not Samuel Beckett. The members of the family all have very distinct personalities, but share a general tendency to enjoy tormenting one another and an unequivocal love of mayhem that often involves audience participation in the form of water-guns and pillow fights. While this striving comic pandemonium separates them from more “serious” circus, they have in common with it an incredible cleverness and wit as they transform experiences of the everyday into something astonishing, whether magical or absurd.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ubX4rhcKA3M

This element of transformation is nowhere better expressed than in the smallest of contemporary circus shows I’ve seen recently, Le Cirque Invisible This astonishing two-person performance is presented by the husband and wife team of Jean-Baptiste Thierrée and Victoria Chaplin (daughter of Charlie). The sixty-year-old Chaplin bamboozles her audience with ingenious costumes that allow her to transform from a dainty coquette into a horse (or a peackock or a lizard or a satellite dish), all right in front of our eyes as she gyres, ambles, and creeps around the stage. It is very much like watching a child at play with elements from its own imagination (all the more so as Chaplin appears to have astonishingly stopped aging at about 14). It brought me back to my early transformations of the living room into invulnerable forts through careful reorganizations of the couches and pillows – forts I could see, feel, and phenomenally inhabit. Chaplin recreates this act of changing the world through pure will, and we cannot help but be drawn into this alchemical process. Paired with Chaplin’s wizardry is the ludicrous, foolish, bewildering magic act of Thierrée (father of James, above). Completely opposite from the “street-magic” hustlers popular in recent years, Thierrée’s work frequently breaks the most central rule of all magic — never let anyone know how it is done. His various magician-personas fly through sequences of familiar tricks so quickly, and with such stereotypical showmanship, that the audience can frequently see the handkerchief up the sleeve or the poorly-palmed coin. It is as if the magician himself is somehow unimpressed with his old tricks as he races through them, some of them quite obviously from the sorts of “magic kits” sold to kids at toy stores. This extraordinary strategy makes the real magic, the tricks that suddenly happen that we cannot explain, all the more head-spinning. Thierrée’s genius is to make the magic itself visible, to secretly occupy a space in common with his audience rather than patronizing them with alleged wizardry.

All four examples of recent contemporary circus, in spite of their diversity, reveal the fascinating place circus today occupies between the real and the unreal. “Reality Television”, when it blossomed onto the cultural scene in the 90’s, made a claim to have some connection with “reality” since it portrayed “real people” in real (if bizarre) situations. Bikini-clad twenty-somethings went spearfishing to “survive”, terrified housewifes ate spiders, silly people went on bad dates, and people got locked in a lavish house where we could watch them squabble. It was all rather sordid and stupid, and everybody knew it was all as fake as professional wrestling, as contrived as any soap opera. During the same period, our pop-cultural images of “unreality” developed an incredible sophistication: We can now quite blithely watch completely believable alien invasions, nuclear Armageddons, natural disasters, and battles with armies of Orcs. Paradoxically, Hollywood’s power to convincingly create absolutely anything destroys our ability to believe in what we see, since we know in advance that it is all a mere product of special effects.

Cirque du Soleil, Corteo, via

In stark contrast, contemporary circus is both far more real and unreal than anything capable of being produced in a movie or television studio. During one act of Cirque du Soleil’s Corteo, a team of jugglers attempted a particularly complicated maneuver and ended up not making it. Rings were dropped and scattered everywhere even after the third attempt. But in this “failure” lies the core success of the circus: these actually are real people doing real things directly in front of us! There were no computer graphics involved when the trapeze artist did a quintuple somersault in the air, and Victoria Chaplin really could have fallen as she eased herself back and forth across a real tight-rope. Circus is first and foremost about reality. Amazing, incredible, breathtaking, and tremendously risky reality.

At the same time, it is also increasingly about unreality, about fantasy. With the move from merely showcasing stunts to generating poetic narratives, contemporary circus is all about the fabrication of another universe, one in which our laws do not apply. The gravity is circus gravity, the laws are circus-laws. In spite of the lack of digital special effects (indeed because of this lack), viewers must imaginatively meet the performers, assisting in the formation of this imaginary world. This is perhaps why I found the Cirque Invisible the most interesting of the four. Chaplin’s transformations, while undeniably ingenious, were not as slick as the special effects in “The Matrix”, nor even as slick as those of Corteo There were occasional awkward gaps and the audible clicking of hidden clips were reminders that these were, after all, costumes. But, by virtue of this, my own imagination was able to step in more actively, to participate in the building of the couch fort. Clearly the same process was happening in Corteo or Parapluie, but Chaplin’s work made this participation itself visible and a part of the act. In making the usually invisible apparatus of imagination itself visible, in portraying its unconscious machinations so forcefully, Chaplin and Thierrée accomplish more powerfully the goals of many avant-garde artists than the artists themselves.

Which reminds me. When we entered the theatre space, a jovial usher politely encouraged us to “enjoy the spectacle”. I was struck by this, as I assumed that the word meant basically the same thing in both French and English. It seemed to me that this fellow was saying something weird, along the lines of “Enjoy the tremendous extravaganza!” But, like so many false cognates in the two languages, the word “spectacle” in French doesn’t have the same hyperbolic connotations as its English homophone, and can be used to describe pretty much any theatrical performance. This got me thinking about Guy Debord, the alcoholic revolutionary who ruled the ranks of the Situationist International with an iron fist, and whose “Society of the Spectacle” has inspired so many MFA students. For Dubord the spectacle was neither a simple theatrical performance, nor a superlative of some sort, but a term to describe an entire complex system of images that have come to “replace” authentic life and which has lead to the creation of the stupefied mass public. Dubord’s solution to this problem involved producing “situations” that might jar and disrupt us from our cretinized stupor. Of course, nothing pleases certain artists more than deprecating an idiotic mass culture of which they are not a part, and the historical avant-garde has always reveled in such mythical elitist foolishness.

But Dubord’s proposed solution of jarring engagement certainly rings a bell with my experience of recent circus performance. Common to all its iterations the circus continues to call us to run away and join it. Our faculties of imagination, curiosity, and wonder (which lie dormant for so many of us in our culture) are summoned to participate in the creation of a world in a way other forms of entertainment technically cannot offer us. The circus viscerally celebrates the body through acrobatics while calling forth the most politically important faculty of our minds, the imagination. Spielberg’s alien might look more realistic than the one Victoria Chaplin could make, but it doesn’t feel as realistic because I didn’t participate in its creation. Everything was done for me before I got there.

Like all entertainment, the circus can be accused of mere escapism, but this is escapism of a positive kind, escape to rather than escape from. For me at least, this escape is lasting: The provocation made to my imagination not only leaves me eager to run away and join the circus but also to realize its unvanquished sense of possibility here in the real world.

]]>