“Lukas, in the middle of the film, the actress will pay a visit. You’ll fall in love with her. And you’ll understand your father. I’ll become your memory. I haven’t shown you the middle yet.”

The words are spoken by a female voice over a black screen at the start of Lukas the Strange (2013). They make a promise while longing for a connection. It’s unclear who both this woman and Lukas are, though she leaves the sense that whatever distance exists between them will be difficult to breach. As the film continues, the voice promises to tell more about what happened—why a man left his family, why a woman grew so sad, and what was in the box that she threw into the “river of forgetting” that encircles the village. “These are things that need telling,” she says out loud, and then wonders, “But how can I tell Lukas without him forgetting?”

In all of the Filipino filmmaker John Torres’ films, stories exist to fill a void that lost memories have left, and throughout them all, the fear lingers that the void will remain. For the rural community in which his fourth feature film unfolds, a void exists in the form of an actress who’s disappeared from the film shoot underway there; for Lukas, a void also exists in the form of his father, who tells the 13 year-old, “Son, I am a tikbalang” before abandoning him. A tikbalang is a creature from Filipino folklore—half-man, half-horse. Lukas goes on to wonder whether he himself will grow up to be one then, as he dons a helmet to play a tikbalang in his town’s film shoot and casts himself in the image of a departed loved one.

Torres (who was born in Manila in 1975) had previously recalled lost loved ones in his second feature, Years When I Was a Child Outside (2008), which recreated his experience of having been separated from his father when he was young. Actors present a version of his family history, with Torres himself narrating from offscreen to “You,” creating the impression of a man reaching out to his younger self. This differed from how Torres had told his own story in the first-person in three early shorts that the critic Alexis Tioseco collectively labeled the “Love Films,” which circled around a longtime love relationship’s end. Yet even though their modes of address differed, the films shared the same impulse: to ease pain through storytelling.

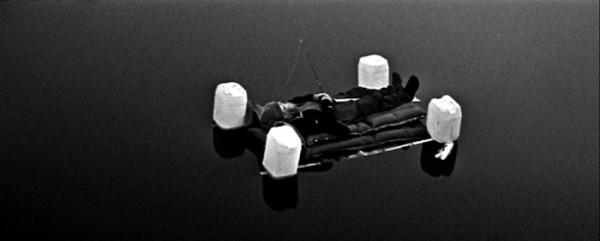

Lukas the Strange, which received its world premiere at this year’s International Film Festival Rotterdam, also does this. Lukas is not just the first film work by an artist who has previously shot exclusively in video, but an overtly retrograde film in its recollection of earlier tales. Early on, brief deteriorated images appear of a young woman walking past villagers, including a young boy. These images, taken from the director Ishmael Bernal’s 1974 film My Husband, Your Lover, offer a prelude to a new work made with the grainy, occasionally flaring visuals and dubbed sound of Filipino films from the 1970s and 1980s. In drawing on this period, Lukas the Strange also invokes the years of the Philippines’ military dictatorship, during which a number of political dissidents were murdered before the military gave way in 1986 to corrupt, neocolonial democracy. As Lukas reenacts the role of his father, the present calls upon memory to help it fight absence and silence; at the same time, the film suggests the pain of remembering to be so great that some forgetting is needed. Like Torres’s other films, Lukas the Strange looks for the middle.

Tell me about Lukas the Strange, or Lukas Nino, as the film is titled in Tagalog. Is the English-language title a direct translation?

The title was supposed to be Lukas Niño [“Lukas Child”]. I was so lazy not to type in the “ñ,” so it became “Lukas Nino.” And “nino” in Tagalog means “whose.” So whose Lukas is this? Does he belong to creatures or to men?

Tell me about how you came up with it.

Man, that’s a hard question. Why do you ask me this?

Well, where did the film come from?

OK. Prepare. I’m going to try to make it really short. I have this film hero, the Filipino director Ishmael Bernal, who’s a contemporary of the better-known Lino Brocka. When festivals think Filipino cinema in the 1980s and 1990s, it’s Lino Brocka, but there’s this equally wonderful filmmaker, Ishmael Bernal, who made his most famous works around the same time. Bernal’s films have a subdued quality to them, a little dream-like, with many things that are unsaid but that you can feel nonetheless, things that are there if you look for them. He has a filmography of 40 films. Around the 15th or 16th title, there’s a lost film. It’s called Scotch on the Rocks to Remember, Black Coffee to Forget (1974). No one saw it, and I thought, “Fuck. The man’s dead, and no one’s even really looking for it.” I didn’t really care what it was. I was just concerned with a space that was left.

I initially wanted—Oh my God, this is going to be a long story. I initially wanted to write a story based on Bernal’s film titles. The sequence of film titles as you read through the filmography chronologically, such that every scene would correspond to a film title, either as a spoken line of dialogue or just looking to the poster of a film for the blocking of a scene. Eventually, though, as time went by, the finances that I had (this film was only supported by the Hubert Bals Fund) weren’t enough to have something very ambitious. I limited myself for the film before the lost film, which is called My Husband, Your Lover (1974). I took inspiration from its milieu and from its major characters and wrote a story. I took out one of the film’s major characters, an aspiring actress. A bit player, a boy seated in one of the scenes as this girl passes him, is Lukas. He is called that because Lukas is my favorite name.

So OK. This is where the milieu and the characters come from. Where another part of the film comes from is one night when I was drinking with a buddy of mine, who’s a poet. He was story-telling the whole night, beginning with, “John, my father, when I was young, told me he was a tikbalang.” A tikbalang is a figure from our folklore. He’s a half-horse, half-man, sort of like a centaur, and a prankster who makes other people lose their way so that they disappear. That’s key—they disappear. I was in a certain mood, and as my buddy was telling me all these stories from his childhood, I began thinking that he was like his father. And how could this possibly be?

At the end of the night we were tipsy. I asked him, “How can you think you are a tikbalang? How did your father tell you this?” And he corrected me: I had misheard one word, which changed everything. He wasn’t a tikbalang—he got tricked by a tikbalang. But by that point I didn’t care. Even in my previous works, I wasn’t fascinated with accuracy or with what really happened. I shot the film before Lukas Nino, Refrains Happen Like Revolutions in a Song (2010), in a land whose language I didn’t bother learning. I didn’t translate the peoples’ dialogue, I just imagined what they were saying and fictionalized everything. I even bastardized all the proper names that referred to their history on the island. I didn’t care. It was my story.

So OK. Cool. There is a third, very important place where Lukas Nino comes from, which is my own experience of watching Filipino films in the 1980s. I was consumed by all these cheesy genre cowboy Western Filipino romantic comedy action films. So consumed, but I also felt a deep self-hatred for liking them. It was an embarrassment. We weren’t supposed to feel proud that we liked this local product, and we are not even supposed to today, especially considering that you have this choice between this crappily-made Filipino film—no color grading, badly dubbed sound, music completely over the top—and slick Hollywood. But the uneven color and unsynched sound were important for me. I wanted to retain them, because they freed me. I’m not so concerned with plot or with story, what I want is feeling. There’s not much of a narrative in my film, I think. But I didn’t care. I just wanted to retain the feeling as a filmmaker wondering, “What if I shot like they did on film?” It’s this older aesthetic that I wanted to capture, even down to little things. For instance, in my film there are no fade-outs, just as there are no fade-outs in old Filipino films—shots start to fade, and then abruptly cut.

All this has to do with my experience of being a moviegoer in the 1980s, though other memories related to cinema have impacted the film as well. Aside from going to the movies when I was young, I got to experience waking up one day and seeing a famous film star on the first floor of our house. People were shooting a film, and she was crying, but only because there was a camera in front of her. Once she crossed the camera, there was a switch, and she wasn’t crying, she was smiling. She played to the crowd. I went out of the house, into the garage, and kicked at just one piece of paper, so that it fell out of position. A crew member told me not to do that again and put the paper back wherever it should have been. It was continuity, and I didn’t know, and I didn’t care, but everything in the house had been transformed. We had been transformed. All the bit players became different creatures and forgot their histories.

What interested you about the people in your film?

The place where we shot the film was my mother’s hometown. I spent summers there during my childhood, but I had not been back between then and making the film. When I returned I just knew that I wanted to talk to my relatives again and see how they had aged. I wanted to catch up on old stories. But I also wanted to be there and try to recreate in my mind how it was to be back in the province, which is around 12 hours north of Manila by bus. While I was curious about the place, I also felt so at home staying there.

Almost all the extras in the film are family members. Before shots, I would tell them the context for the scene—this is supposed to be a film shoot, and we’re shooting this film shoot, so just act normal. It was meant to be like we were casting. And we Filipinos are very, very close to this experience because with our soap operas and our films it’s normal to just have people being asked to play bit roles. They’re at home with this, so the asking is almost never a problem, and in this case there was no difficulty, either. We didn’t have formal discussions about what the film would be, nor about whether they would be paid for their work. They were just glad to be part of it, and wanted to have DVDs to watch when it was done.

The boy who plays Lukas is a nephew of mine who I never really got to know until making the film. Part of the reason for making it was that I was very interested in shooting him, and the film served as a good excuse. I discovered the actor who plays his father through a sort of chance encounter. After shooting for a few days, we realized that we had left something in Manila, so we had to go to the bus terminal to return. It was around 4 A.M., we hadn’t relaxed, we hadn’t slept, and then we suddenly saw this Elvis creature of a man who so rock-and-roll in his movements as he charmed all the women in a small eatery. I knew he was it—I had been looking for someone who resembled a tikbalang. And as it turned out, he was a distant relative of mine.

Tell me about the river of forgetting.

OK. OK OK. I have always vowed to make something simple and easily followable, but always, always, always the films are situated in my history, in our country, and in our past, and these things are not so easy to follow. The river, I think, for me, is a reference to the Marcos dictatorship that ended in the late 1980s. Because I grew up in a household that was largely Marcos loyalist, my picture of Manila was much cleaner than the city actually was. News of bodies disappearing, enemies of the administration salvaged and later found on the wayside, under thick bushes, or thrown in water, were rampant, but I still grew up believing that we needed one strong man, a dictator, to keep society in order. I then thought that we needed discipline as this “new society” moved forward along the road to progress. I was too young to experience needing to be home early because of curfews or having to join rallies. I never had anyone close in my family who was an activist, so I never really knew how it was to see loved ones disappear. But today I always hear of Marcos’s cronies and the military conspiring to take away civilians who were too outspoken against the administration, and when I was making this film, I was fascinated by how the ex-military men are living their lives now.

There’s a big representation in the film of what color people wear, red or yellow. In Filipino history, yellow stands for democracy, and red for dictatorship. (In the film the film crew wears red, and Lukas’s helmet is red and yellow.) I would always think that maybe those people who would want to forget are people like Marcos’s soldiers, who made other people disappear. I think it’s easier for them to forget. They’re wired for crossing the river. Not anyone can do it. It takes great strength and fortitude. I think that they’re the ones who really need to forget.

I was wondering about disappearing bodies. How can one person really think he is a tikbalang? Maybe there’s this cycle of disappearance in his life, and in the 1980s, salvaging people—meaning dumping them into fields so that they never get to be seen again—was done by Marcos’s police and soldiers. These military men are so much like the tikbalangs in my film. By throwing bodies into empty lots and fields, they have also made people disappear. I even imagine them looking like tikbalangs, their appearance mutating, similar to those changes in a soldier’s face coming home after his first experience of battle. Sorrow and guilt housed in a chest for years can mutate someone into a hybrid of man and beast.

So I was thinking maybe if we had the father as well as ex-military men, what if they were thrown into this island together? How would they be able to cope? They would need to invent a river so that they could forget, I thought. (Initially I didn’t know it, but I was making a reference to the River Lethe, which in Greek mythology can supposedly be its own river of forgetting—you forget things if you drink its water.)

And I also need the river. I think that part of the film is my saying that I don’t care about the wounds pain leaves behind. I think it’s much simpler to have this river instead. My past is contained there. Growing up, my father was my idol. He wrote storybooks for children and how-to books for adults, and he earned enough money for us to afford a better life than we would have had without him. I always put him on a pedestal. He was the reason I got started with video-making—he always spent so much on camera and other gear that I was able to start early and use cameras for school projects and practice editing well before college. But my father broke our hearts when I was a young man, when we learned that he had a secret life with another family that lived near us. This is explicitly the subject of my second feature, Years When I Was a Child Outside, but with Lukas the Strange, there is also much of my father in Lukas’s father.

So the river contains many things that have been lost. Lost people. Lost film. Lost instances. Lost moments. But we also find things in the river, like the tapes of this woman guiding Lukas and narrating his story.

How did you come up with the writing that appears onscreen?

First off, it’s very much ingrained with the process that I’ve set for myself, even with my short films. Inter-titles and subtitles are always onscreen. But with this project we decided that I would use inter-titles when the narrator had difficulty in admitting something to Lukas—something really serious that could change her relationship with him. There are also some things that cannot be said. She tells him, “There are some things that I can tell you, but there are some things that I can’t say.” And these things are presented as titles flashed onscreen while Lukas remains silent.

In my previous works, I have always had different starting points, although process-wise, I think that Lukas the Strange continues my desire to strip down what I have done so far and what I can do and see what else is there, so that I know what remains in my work and what changes in it. One particular difference from my previous work to this film is the use of my own voice for voiceover. Previously, I would always narrate, even in my short films. But I was really tired of hearing my voice all the time, and on this film I wanted to see how it initially was to tell a story without a narrator. Eventually, though, that didn’t seem right, either, and I felt the wrongness in my gut. I thought I was missing someone. I was missing my friend who was telling me about his father and about his true-to-life childhood. I missed this possibility of mishearing this narrator/friend, this chance to hear someone who might be making up or mixing up the story after all. I missed the confused voice of a troubled soul. And so I made a big, big creative decision to have this witness—or this friend/muse—narrate everything. This person who is everywhere, who is somehow remembering all these things—not exactly creating from scratch, or representing what really happened. She’s telling a story.

Do you believe there is love in Lukas the Strange?

There’s love. Love is my first instinct, my first impulse to do this. It’s always about this, in this film as well as in my others. And I can’t tell you in words how love is vital to them, so maybe the films are enough.

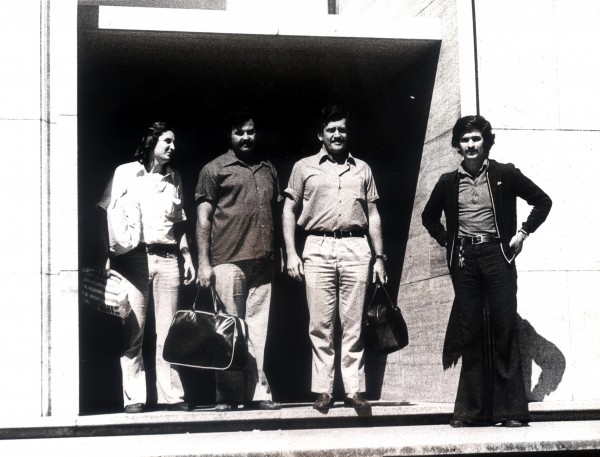

All images accompanying this interview were provided by John Torres. The interview was conducted at the 2013 edition of the International Film Festival Rotterdam, which also screened a film produced by Torres. Shireen Seno’s Big Boy tells the story of a postcolonial Filipino family stretching their first-born son’s limbs as far as possible in the name of progress.

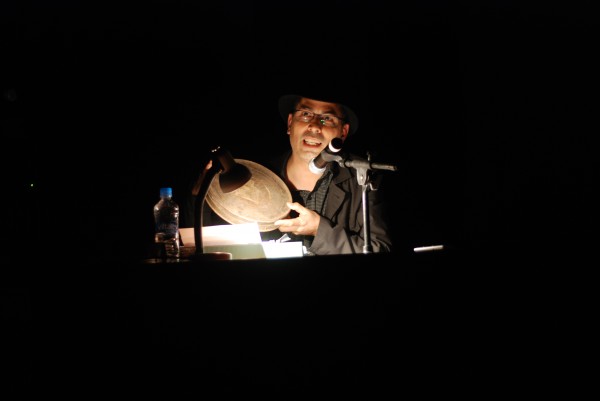

]]>It was an October afternoon last year at the Brooklyn screening space UnionDocs, and our group of five was awaiting David Gatten. He arrived distinctly attired—small-lensed glasses, a scraggly beard, overalls, and a heavy knapsack, from which he removed prints of eight of his eighteen completed 16mm films. Some he hadn’t brought because he’d made them to be shown at an outdated projector speed; one was unavailable because his print remained in California under an old girlfriend’s care. But the films he had on hand he would project himself and discuss with us.

This is a frequent practice for Gatten, who was in New York for the world premiere of his latest work, The Extravagant Shadows, at the New York Film Festival’s Views from the Avant-Garde sidebar. We arranged our private screening because we might never see his remaining works otherwise. His films are unique art objects, rendering chances to view them rare. He explained that no more than three prints of any exist; some, like the What the Water Said series (unprocessed filmstrips exploding with sound and color, the product of Gatten leaving them floating in crab traps off the South Carolina coast), could never be reproduced. Each time a film of his runs through a projector, he said, it dies a little.

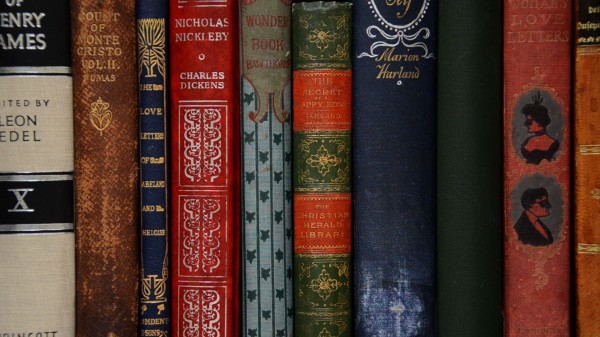

These delicate, fragile works need care and attention to survive, much like a key Gatten subject: love. And like much of the output of his self-professed model, Hollis Frampton (whose ode to his own maternal grandmother, Gloria! [1979], is Gatten’s favorite film), they devote themselves to building systematic frames within which love can be articulated. The frames are often made from forms of written language, whether densely coded Western Union messages (Film for Invisible Ink, case no. 323: ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST [2010], prepared for his wedding to fellow filmmaker Erin Espelie) or phrases plucked out of direct, despairing summons written to a beloved from across an ocean (The Great Art of Knowing [2004]). His most celebrated project has been an ongoing nine-part film series, begun in the late 1990s, called The Secret History of the Dividing Line, with each entry named after a book belonging to 18th-century Richmond, Virginia founder William Byrd II, whose library contained over 4,000 volumes. The series’ four completed films, all silent (though Gatten prefers to call them quiet) and three of the four in black-and-white, tremble with close-ups of thick, richly engraved words soon to disappear from sight.

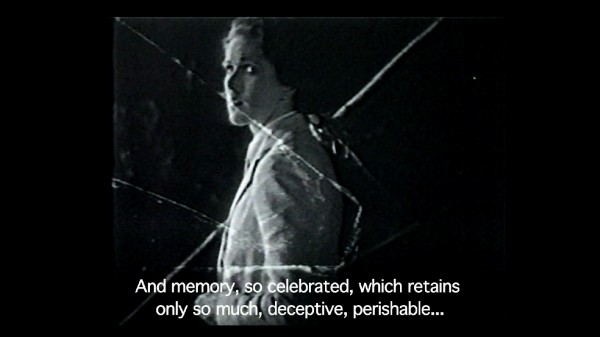

It takes words much longer to vanish in The Extravagant Shadows, Gatten’s first digital work, which will be screening again in New York (in a session curated by Views programmer Mark McElhatten) at Lincoln Center on Monday, April 29 at 7 P.M. with Gatten in person. They fade in, ghostlike, forming cryptic messages over layers of paint with which the artist has covered a bookcase’s glass front, then haunt the screen for several minutes as they fade back out. Though many originally come from other writers, including Stefan Zweig, Maurice Blanchot, and Henry James (from whose short story “The Jolly Corner” Gatten took Shadows’ title), the tale that they obliquely tell—made up of overlapping possible stories that lovers might share, if chance allows—is of Gatten’s invention.

How did you learn to read?

I cannot completely remember learning to read, but I know that books were always a tremendously important part of the household. We did not listen to a lot of music. Music was not on all the time, and was a very special event when it was played. Books formed the architecture of our home. My mother majored in Shakespeare at William & Mary. My father would read to us for an hour every night and my mother would read on the weekends. My earliest memories of literature are of having it read aloud to me. I am certain that Dr. Seuss was an important beginning, and I feel like I learned to read and took pleasure in reading early on. My parents would take us to the library every week, where we were allowed only three books. That wasn’t a library policy, but a family policy, which put into place an idea of scarcity, and a need to then choose carefully. Books were serious and special things. So I spent all of my allowance money on buying them.

My relationship to the written word became problematic when I tried to learn to write cursive, because in the 1970s in North Carolina public schools, if you were left-handed you were still referred to as “the Devil’s child.” As a left-handed person I was too much for the teacher, and was put in the corner with crayons to draw while everyone else learned to write. I have never had an easy relationship with my own handwriting, and in fact, much of the time I cannot read anything that I write. I believe that this problem has become a fundamentally important condition for my thinking about text as image in cinema, and issues of legibility and illegibility. Hardwood Process (1996) is largely a movie about my inability to read my own diary. The film has 14 sections, each beginning with a phrase. It’s all stuff that I couldn’t read, but that I knew was important. So I had to make images to complete the phrases. Even today, at age 41, I am still frequently unable to read something I have written by hand. I am still learning how to read on a daily basis.

How?

I’ve learned to read very differently based on the kind of books I have been reading. David Markson is one of the two “skeleton key” writers that have inspired and informed my cinema—the other being Susan Howe, especially her book The Non-Conformist’s Memorial (1993), and within it the poem “Melville’s Marginalia.” Although my method of writing and condensing writing was pretty well developed by the time I read Markson’s This Is Not a Novel in 2001, I feel I was deeply altered by it—and then also by a subsequent reading of Vanishing Point (2004). I found it both one of the funniest and one of the most emotionally devastating reading experiences of my life. I think there could never have been the Films for Invisible Ink [a series of films specifically made for friends and loved ones]—especially the first one, Film for Invisible Ink, case no. 71: BASE-PLUS-FOG (2006) [made for Gatten’s first wife, Weena Perry]—without it. And I’ve been going to school with Markson ever since. Those last five novels of his speak so strongly and directly to a poetic and narrative strategy that I find moving as a reader and, at this point one happily and nearly inevitability at play in my own work as a filmmaker. Touchstone works by a writer of enormous humanity.

I also learned how to read over the last seven years from reading Henry James.

How did James inform The Extravagant Shadows?

“The Birthplace,” the short tale in which the young couple is caretaking Shakespeare’s cottage, is the first James text that appears. It initiates a narrative about a young couple going to live in a place that is inhabited by a spirit they can’t see, but with whom they want to commune. I used this tale as the launching pad. It immediately seemed related to, but different from, the James tale, “The Jolly Corner,” which is about a man who is going back to a house that he owns but hasn’t been to for years, and who, as he starts to visit it, also starts to recognize the life he might have led. “The Jolly Corner” is, in my reading, very much about a consideration of another self. Those two stories I had read many years before and confused. They had been condensing for years in my brain before I came back to try and capture something of them on paper.

So there were situations and a narrative thematic that James provided immediately. But much more important was the way in which he deploys language to describe a series of events, which might be actions in the external world or the internal clockworks of emotions and of decision-making processes. The way he will circle around something, with the most important things being what he leaves unsaid. He makes beautiful outlines with language. I was interested in the specific instances of language he uses to do that, but also in his greater approach to storytelling. All of the storytelling in The Extravagant Shadows is based in a late Jamesian mode of proceeding through an event, an idea, a character, or an emotion.

James is there in almost every panel of text. I wrote most of the text myself, but I was writing in relation to James almost the entire time. James makes visible the process of thought, which of course happens very fast, but through his use of language, he slows it down so that we are able to understand someone else’s thinking. A character’s, but also his own, with all the hesitations and circling back in slow motion, which allows for analytic examination. With The Extravagant Shadows I’m trying to do that. I don’t think it’s a slow film, but it is a place to reside in for a long time. I hope that there is a lot of time to consider small details, whether those are details of language, of paint, or of light shifting.

How did The Extravagant Shadows form?

I have always worked slowly, but the older I get the slower I am working, and the longer I am willing to work on a project. The Extravagant Shadows began in 1998 with an idea about certain pieces of language, based in Blanchot. I knew I wanted to make a work where language was staging itself very, very slowly, much more slowly than I could accomplish with what I knew about filmmaking at the time. I was in graduate school at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and was doing a lot of contact printing and optical printing. On a contact printer the longest fade you can have is 96 frames, or four seconds. On a small JK optical printer it’s very difficult to make something longer than four seconds, and I knew I wanted fades to last minutes, and for things to hover on the edge of legibility for minutes. I knew that I wanted to work with an analogue video image and text generating, so that I could have a different kind of control over time. I assumed that this work was going to be an analogue tape. There was very little text then compared to what there is now. It was going to be a much shorter piece, maybe half an hour long. But I didn’t know how to make it, and it wasn’t urgent to make at that moment, and other projects took over. This was at the same time that I was discovering the Byrd project, and that took hold strong. So The Extravagant Shadows, which wasn’t even called that then (I think it was called Area Effect), just sat.

I came back to it a few years later and fiddled with the text some more. A lot of what I do in the studio is sit and write. I’m not always working with strips of film. I’m not always in the darkroom. It is often reading and writing. The studio is a place to consider words, and to structure my own words, as well as to produce images. So I would write. Sometimes if I got stuck on another project I would return, but I mainly kept putting it aside, and putting it aside. I’d shot some stuff on VHS that didn’t have anything to do with the images that we’re looking at now. I was actually shooting a TV monitor of a snowstorm on bad antennae reception. There was the snow of the storm that the weather channel was covering and there was the snow on the screen itself, and that was serving as a background for these words to emerge from. And I thought that that was interesting, but I wasn’t wild about it. I knew at a certain point that I was going to work with a mini-DV camera, but that didn’t end up going anywhere either.

Then I moved to New York in 2006, finished the first Invisible Ink film, BASE-PLUS-FOG, and went back to what, at that point, I knew to be The Extravagant Shadows. I was reading Henry James on a daily basis, and conversing with a friend who was also reading James. We would wake up every morning, call each other, and ask, “What’d you read last night? How was it?” For two years we were reading James almost every day. Mostly not the novels—mostly it was the tales. We systematically made our way through nearly all 112 tales, and talked about them, and that is when the piece started to find the shape that it has now. I knew it was going to have a Jamesian structure, that the characters, the situations, the ambiguities, the events would have something to do with the way James represented the world through language. And that there would be phrases, but that I was going to write through them, around them, and to connect things from a dozen of the different tales to make a new story that doesn’t exist in any James tale, that doesn’t exist in any Blanchot book, but that borrowed from and condensed them.

I use the term “condensation” in relation to texts. I am trying to build cinematic structures that replicate the process of condensation within a glass of water, allowing for things that are in the air to be fixed, find new form, and group together as visible, light-catching substances. What I’m trying to pull out of the air is language. These cultural productions that exist as books, I’m trying to build a cinematic structure to condense them. It’s an active reading process, first of all. It’s recognizing that this phrase connects to this phrase, and that if there’s this idea here, and there’s another idea 18 inches away, I’ve got to then use language to make the connection to draw these two things together. I believe that poetry often operates as a kind of condensation which functions through ellipsis, an economy of means, and a high level of organization. Shape is important in poetry. It’s deeply important in prose as well, but there it’s articulated in a different way, and often at a different length. I am trying to boil down experience and language into a smaller vessel. I am still working out this poetics, and am just starting to understand it as a tool, rather than something that I recognize that I do. I didn’t say, when I started doing this, “Now I will condense this text.” I just found myself doing it, and it was during the last couple of years of writing The Extravagant Shadows that I came to understand it as an approach that I can apply to any existing text to make a set of new meanings. To take, as I do, a Wallace Stevens poem, “Description Without Place,” and condense it into 24 lines by taking certain ideas, leapfrogging over others, and forming a new poem. With Stevens, with James, with Blanchot.

That writing process took up a lot of time. But it was only once I started teaching at Duke University in 2010, and once Erin and I moved to the cottage we live in when we are at Duke, that things really coalesced. I started shooting the cottage walls because I love the colors the walls are painted, which were the existing colors when we moved in. Home is really Salinas, Colorado, all of our things are in the cabin there, and the Durham cottage is quite minimal by comparison. We don’t put things on the cottage walls. The walls are painted, and the paint is beautiful. I felt that the walls were speaking.

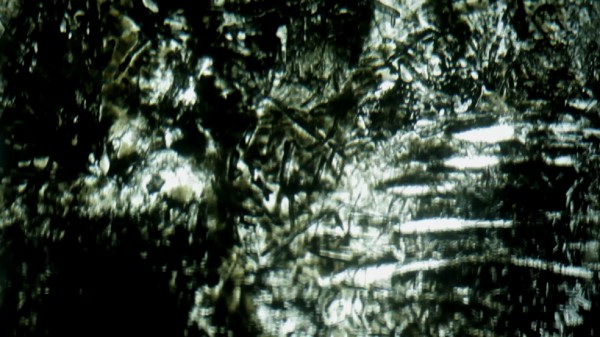

In 2011, I started filming—not filming, but shooting with Erin’s Nikon D-7000. I started making images and recording sound in the cottage. I was so inspired by the paint that I wanted to start painting myself, mix paints, and experiment with layering colors and producing effects of color and light rendered digitally. All of the painting that we see in the final form of The Extravagant Shadows was performed in May, June, and July of 2012 in Colorado outside the cabin. It was very important to do the painting outside, where the clouds could move across the sun and change the color temperature and affect that world of paint. I didn’t want it to be a static, studio-lit situation. I wanted low relative humidity to help the paint dry, and I wanted the paint to be alive to the changing of light.

So it was a circuitous path, with a lot of stop-and-start. And then, as there often is, there came a moment when I could think about nothing else. I was intending to finish the new Byrd film, but The Extravagant Shadows said, “No.” I was so surprised. I’ve been making work for a while, and I know what I’m doing as a 16mm filmmaker. I’m deeply surprised about what happened with digital cinema and The Extravagant Shadows.

What is your background in painting?

It stretches all the way back to May of 2012. I had never painted anything before then, except for places where I had lived, where I was just painting the walls. I wasn’t painting pictures, I was applying paint, which I like to do, but I had never painted before. I like to look at paintings a lot, though. Adriaen Coorte’s painting White Asparagus at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam—in which the white paint has faded to the point at which the image of the asparagus is really a translucent ghost of itself—is probably my favorite painting. And then I often think most of my filmmaking operates in relation to experiences I’ve had with Agnes Martin’s work.

Part of what I’m interested in in cinema is exploring materials. With the What the Water Said project, I put into play the substances of the ocean, the river, and the filmstrip. I didn’t know what was going to happen—all I did was throw the celluloid into the water. With The Extravagant Shadows I chose different kinds of paints. I chose oil-based enamel paint and acrylic paint, and I layered those on top of each other and let them make the picture. I didn’t control—I just wanted to see what would happen with the relative humidity of the air, the intensity of the sunlight, and the way that those paints reacted to each other. They’re not made to be used in tandem like that. So it was about letting the materials articulate themselves.

As the movie goes on, I start to do things with the brush to provide different conditions for them to articulate themselves into different kinds of images. The paintbrush starts to activate different characteristics of the paint. It starts to layer or smudge things, or work with one layer before the other layer is completely dry. I was learning. I was listening and watching the paint as the shoot went on, and trying to respond to what I was learning. I then started making some paintings, but found that they weren’t interesting to me. What I was interested in was seeing paint dry. As soon as the paint would dry, I would apply more paint, so that it was never dry and always drying. The painting never finishes. It never stabilizes. It’s always changing.

What are the extravagant shadows?

For me, first and foremost, they are language. It’s the words themselves—and the ideas, stories and emotions they describe—that can’t be contained, erased, painted over. They are so extravagant that they cannot be effaced. I was keenly aware when making this that it was a digital work, and that as a digital work, it in some ways flew in the face of the aesthetics of the mostly black-and-white 16mm Byrd work—and most everything else I’ve made. And many of those films—The Great Art of Knowing [second film in the Byrd sequence], The Enjoyment of Reading (Lost and Found) [2001, fourth film in the Byrd sequence], the new, still-unfinished Byrd film in particular—are filled with shadows, with dappled light, with extravagant expressions of light and dark, kinetic (and I believe beautiful) expressions of light modulated through shadow. Those films are filled with extravagant shadows. My guess is that when people see this new title and think of my work, they’re thinking of visual shadows. But I wanted to get at something less literal. The early gesture of painting out the books is, I think, a notice that this isn’t going to be the same space. We’re not going to be considering the book-as-object. We’re going to be considering what the book contains, and what it might evoke, as opposed to represent. There are shadows in this digital work, and there are reflections, but they are considerably more subtle, although perhaps no less extravagant, than in the 16mm work.

Do you feel these shadows coming to life?

That’s the goal, and I hope they do. I ‘m moved that viewers thus far have seemed so committed to giving them life through their attention. That’s the only way they can come to life—through someone’s concentrated and generous imagination.

There are certain kinds of movie experiences—which I love having—where everything is largely determined. If you go to see the Lord of the Rings movies or the Jason Bourne films or a Soderbergh in a certain mode, then you are going to live inside a world that is built almost airtight and perfectly articulated. You will identify with characters, you will lose yourself, the meaning is blazing off the screen, and you are actively subsumed in it. This is one kind of experience, which commercial cinema frequently seeks to produce.

My background of consuming and enjoying that probably helped me conceive work that was different from commercial cinema, and closer to the aesthetic experience of the fine arts. I admire the idea of the oppositional cinema, but what I’m making is just in favor of itself, and not necessarily opposed to something else—I like the other thing too, it just isn’t what I’m doing. I prefer to think of cinema as an ecosystem with different kinds of works existing at various points along a continuum rather than simply being in opposition to each other. For the kind of experience I seek, I don’t want anyone to forget who they are or where they are, and I want my viewers to be active in a different way. I want the chief activity to be that of the viewer approaching the screen, and for the meaning of the work not to be inherent, but rather to be a product of someone’s engagement with it.

Now, that is not to say that anything goes.Rather, it means that my job as a filmmaker is to define a field of play containing multiple paths. This is what Umberto Eco describes in his great book, The Open Work (1962). When I encountered that book in graduate school it articulated many things that I was feeling about experimental and avant-garde cinema and that I admired, but that I couldn’t articulate for myself.

Why don’t you attribute the source texts in The Extravagant Shadows?

I have made some attempt at attribution in the printed material, but not in the work itself. I use other peoples’ texts in almost everything I make. Quite often there are attributions at the end of the films, and quite often there are not. My name appears at the end of some works and not in others. Because that is a shot, it’s not just credits. That’s the last shot of the movie. I am thinking about these things as images. I could not possibly end Secret History of the Dividing Line [2002, first film in the Byrd sequence] after the words “Here ends the Secret History” by then putting “David Gatten 2002.” That would be preposterous. That would be another image. Here would not have ended the secret history: it wouldn’t be over yet. I would never put my name at the end of The Great Art of Knowing. That would be like a desecration of what I was trying to do. Yet at the end of the next two Byrd films, I not only refer to texts, but my name is on the films. In Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises, or the Doctrine of Handy-Works Applied to the Art of Printing [1999, third film in the Byrd sequence] I cite the translations, the translators, sometimes the press itself, because that was a book about translation and the printing press, and so that is an appropriate image with which to end that film. That wasn’t an image that I wanted to end The Extravagant Shadows with. I wasn’t going to go to a black screen after those books. The last image of that film had to be book spines. So there was not an appropriate place within the image sequence to put that attribution information. It’s not secret. It’s not that I don’t want people to know. It’s just that there is not an appropriate place to relate that onscreen. It’s an aesthetic concern. Other filmmakers often use credits as bookends. For me they’re covers.

Did you see a similarity in the relationships between celluloid and digital photography and between the physical book and digital text?

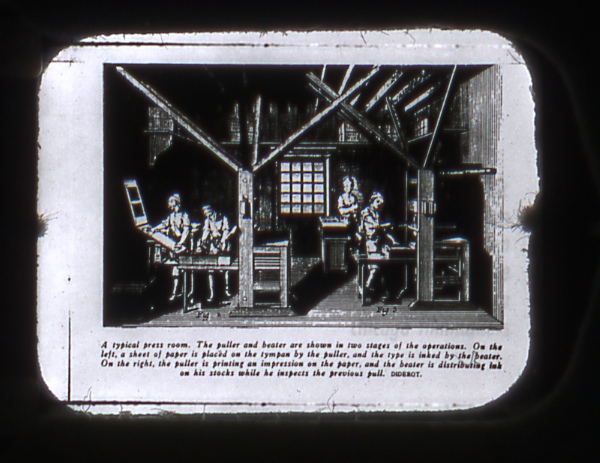

I didn’t think much about digital text—in the form of electronic books or reader devices per se. I’ve seen people on the subway carrying these E-readers, but I’ve never actually held one nor tried to read from one. So I suppose it is amusing at some level that I’ve made a three-hour movie that is all digital text and is essentially an electronic reader. I really wasn’t thinking about it in those terms while making it—I was more concerned with, and interested in, the difference between working with celluloid film titles and computer-generated text. Of course we’re going through a tremendous change in print culture—we can’t even call it print culture anymore—reading culture—in the same way that we are going through a transition with the moving image. I have addressed this before. The transition from celluloid to digital I was trying to get at in 1999, when I made Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises. Joseph Moxon produced the first manual of style to tell printers how to print. I was trying to go back to the moment when we moved from scribal reproduction to mechanical reproduction of texts with Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press and the printing of the Gutenberg Bible. One can then draw the celluloid-digital analogy within The Extravagant Shadows, where at the beginning I put the books away and then bring out the text. The object disappears, but the text persists. I suppose at that level it is some sort of comment on the status of the book in the 21st century.

It is largely a quiet film, but there is some sound. How did you make your soundtrack choices?

The music—five songs from a 1968 Merrilee Rush album called Angel of the Morning—I took as the soundtrack. I was interested in using those songs as texts in the exact same way I was considering works by Henry James, Stefan Zweig, Roger Gard, and Lao Yee-Cheung. They are conveying narrative information, in a voice that has emotion and phrasing. I was thinking of the songs as another set of texts, manifesting language differently. Not just onscreen, visual language, but sung language. And all of those songs have particular emotional dynamics that intersect with some of the narrative thrust or the situations in the other texts.

That’s about the music. One of the big differences between shooting 16mm film on a Bolex and shooting digital images on a Nikon D-7000 is that the digital camera assumes sound. It automatically records synchronous sound, whereas a Bolex does not. It’s actually tortuously difficult to record synchronous sound in film. You’ve really got to make a point of it. And with a Digital SLR (DSLR) you’ve got to turn off the sound. You’ve got to go to a bit of trouble to make it a silent recording. So it felt important to acknowledge that, and to let there be a moment where the image gains dimension through the genuine synchronous sound of a particular place. I make that gesture at the moment in the movie when I want to address sound. Up to that point—one hour and 18 minutes—there has been a lot of mention of sounds and spoken language. In all sections of the narrative thus far, the text speaks about characters hearing things. So I hope that we are primed as viewers to already be thinking about what it means to hear something. I then wanted us to hear something, and then I wanted that to go away. It was important to explore something that I had never explored before, but that is inherent in working with a new digital camera.

A few days before I saw the film, you told me that Hollis Frampton’s film Gloria! would help me make better sense of it. It might have been because of the way that Frampton uses music. How do you see the usage of music in the two films as synchronous, and what other synchronicities do you see?

When I saw Gloria!, I felt Frampton was almost reminding me that music is appropriate, in the same way that I think he reminded a lot of people that language is an appropriate area of exploration. Coming out of an American avant-garde cinema as articulated by Stan Brakhage, which was largely about a perception beyond or before language, Frampton brought us back to language. And I experienced very powerfully his use of music. But it’s not just the use of music in Gloria! that is important in relation to The Extravagant Shadows. That music has been described in language before we ever hear it. It’s an example of a seed that he plants. In one of those statements about his grandmother, he describes the music, so when the music comes on later there is a recognition. We have an epiphany that now we are hearing the wedding music. So it’s not just that the music is there, it’s that we know what this music is based on a prior experience we’ve had. We have learned something. The relationship between language and music in Gloria!—very different than Bruce Conner or Lewis Klahr or Bruce Baillie’s powerful usages of music—helped me understand what was possible. Frampton was setting us up for music to mean something within a context that he had already provided for us.

I was completely knocked out by this way of structuring an emotional experience. So I wanted to explore it myself. Long before “Angel of the Morning” comes on, bits of the lyrics are onscreen. You would have to be a Merrilee Rush fan and know that song pretty well to recognize some of the early phrases, but it is certainly my hope that, after the songs have come on and lyrics continue to appear, you make that connection.

You studied acting when you were younger. How has your actor’s training informed your filmmaking?

I sometimes think of myself not as a filmmaker per se, but a performer, and that I use these films as highly elaborate and painstakingly crafted props. Because I believe that when I’m lucky enough to be present and speaking with a film that what I say beforehand and afterwards is part of my work as an artist. Both the work of speaking and the work that occurs onscreen have to do with activating public space and putting into play a range of ideas. I don’t believe that the work that is on screen must stand alone. Nothing stands alone. Everything operates within a context. Some contexts are more familiar than others, but everything has one, and so I am interested in what happens when I plant seeds in an introduction to a piece of work. That’s part of the composition. It was a strategic decision to begin the premiere of The Extravagant Shadows by speaking about Eric Gill, who is never referred to explicitly within the film itself, although if you know the typeface Gill Sans, you see that a lot of the type is set in Gill Sans and a lot is set in Perpetua, and that there are locations in the film that figured into Eric Gill’s life. I hoped that there would be little moments of recognition. That is where the theater background comes in, because it’s a bit of a performance—it’s thought out—it is part of the composition.

The other way in which being on stage for about a decade has affected my filmmaking is that it made possible, right away, a certain comfort level with, and really, an interest in, the performative aspects of being a teacher. I’m proud of the work that I have done in the classroom and I am grateful that my various academic teaching jobs have provided a structure, both temporally and economically, for me to continue my filmmaking practice. I feel I have been successful as a teacher in large measure because of how I am able to combine what I know and what I believe about cinema with what I am able to do in the classroom as a performer. This has in turn now informed my ideas of how to structure a three-hour block of time with the moving image. At Duke I teach a three-and-a-half-hour class twice a week, and each class is its own composition. I write an essay and I speak each word, I memorize 95 percent of it so that I can mostly deliver it as a monologue, and I try to structure the articulation of meaning in the classroom in the same way that I try to in The Extravagant Shadows. These last three years mark the first time in this 16-year period when I have been making films and teaching that the practices have intersected and are traveling alongside each other.

How so?

Largely through thinking about how meaning accrues in the classroom. I got more interested in thinking about those strategies partly based on some film materials I was working with. In 2001 my grad school friend Ken Eisenstein sent me several 3 x 5 instructional pamphlets from the Little Blue Book series (1919-1978)—How to Write Letters for All Occasions, Home Vegetable Gardening, and The Enjoyment of Reading. This Little Blue Book series is kind of astonishing. Over a thousand of these things on nearly every possible topic that you could ever want to know anything about. What You Need to Know About Phrenology. How to Conduct a Love Affair. I was fascinated by these didactic texts. They then became important in several of my films. These were my first works of condensation as a writing process. The film The Enjoyment of Reading (Lost and Found), which begins with five screens of condensed text from the pamphlet The Enjoyment of Reading, is the very first. Do I need an instructional text about these things, and in what ways do these reduce one’s experience of the world?

My theory of pedagogy at this point, having taught for 16 years and watched things work and fail in the classroom, is that it is most interesting to proceed first by producing a kind of confusion for students. My idea is that, in any given class, the first half should be about the production of a confusion that encourages curiosity while destabilizing a student’s comfort level with the material. Everything I do should raise questions. “Why is he talking about that? How is that relevant to film? He’s talking about music, he’s talking about poetry, he’s talking about opera, he’s talking about gardening. How does this have anything to do with a film class?” And then the second half of class should exist partially in order to relieve some of that confusion, but in a way that is, again, like planting seeds that are going to blossom into a series of recognitions later. I am not telling them something, they have to make the connections themselves. They have to be present, alert. But then when they do make that recognition, it’s far more powerful than if I had just told them the answer to begin with, because they’re discovering it on their own. So by the end of a class, I hope that 90 percent of the confusion is relieved through a series of revelations, and if it’s really going well, epiphanies, that then transmute that last 10 percent of confusion into mystery. And that mystery is what propels you to the next class, where it changes back into confusion. And so on.

That’s what I’m trying to do each week in the classroom, and increasingly in my filmmaking. Film for Invisible Ink, case no. 323: ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST is a prime example. “What is this? How are these phrases related to anything?” But I hope that by the end, some sort of transmutation has taken place, and that these things that were simply Western Union telegraphic code phrases now take on new meanings in the context of a series of wedding vows. The Extravagant Shadows is the fullest exploration of this way of working, and the deepest I’ve gone into planning nested stories, setting things up that pay off later, while being at peace with the risk of confusing viewers for 15 or 20 minutes so that an hour and a half down the line it becomes clear from context why that material was there.

Who are the human figures in the film?

Well, visually, there’s my reflection in the window and in the paint, with my hand blocking light, or my body blocking sunlight. It’s one of the relatively few times that a human body has appeared in my cinema. I didn’t initially decide to present myself. I saw that I was reflected in the glass, and had to consider whether to eliminate my image. And I decided that it was appropriate to see me. Since you were already going to see my hand, it’s not off the table to see the reflection of my whole body.

The other human figures in the film are people that I’ve encountered in books and appear in the movie represented by language. Some are characters—or composites of characters—from stories by James and Blanchot. I recognize one of them as being Henry James himself. And I recognize two of them as being Erin and myself. And I think that at this early stage of getting to know this new work that’s all I’ll say about them.

What is your interest in ghost stories?

They form one manifestation of my interest in desire across distance, whether temporal or geographic. There is something that can’t quite be reached, present but immaterial, that is the haunting. It is the past manifested imperfectly in the present. It’s a cultural form with which we are familiar, and therefore fertile as one way to articulate the difficulty of desire.

Desire, of course, is connected to love, which I first learned about from watching my parents. I have a very good model, and learned by example. They take a lot of care with each other, and they were never afraid to speak to me about the care that they take. I always knew that they loved each other, but that that was not sufficient. You have to take care with that love. Love is a thing that is both robust and fragile, and so you have to care for it. I also learned about love from books. M. M. Kaye’s The Far Pavilions (1978) was a childhood experience of a story about love across time and space that has certainly informed what I do in the cinema. And not just the book, but also that 1983 HBO miniseries adaptation starring Ben Cross, Amy Irving, Omar Sharif, and Christopher Lee. That was a major, major thing for a 12-year-old boy thinking about love, and that’s reverberated throughout my life and my filmmaking, in the same way that Edith Wharton’s novel The Age of Innocence (1920) has.

I have also learned about love from being married to Weena. At that time I wasn’t ready to be a good partner or a good husband. I was struggling so hard to be a filmmaker and a film teacher and a good husband that all three of those things suffered. That was a hard time, and I still have deep sadness from having failed at it. But it taught me what was required of me. I have since learned about love, and how to love, on a daily basis with Erin. I am trying very hard not to make the same mistakes. I make other mistakes. I make new mistakes all the time. But that’s part of learning.

How is Erin in The Extravagant Shadows?

I’m maybe a little hesitant to even answer that. But in a way I already have, I guess. At one level she—well, both of us, really, are characters in it. We appear as figures in the text. She reads aloud to me when I cook, and I read aloud to her when she cooks, and she reads aloud while I do the dishes. We live in an old gold mining cabin when in Colorado and a little cottage when we are at Duke, so for me, the couple in the cottage, with the lamplight, is very much a representation of our engagement with literature and how we share literature through reading aloud to each other. That story is one of the frames for The Extravagant Shadows. And that act is one of the frames for our daily life.

That’s how I’d say she is in it explicitly. But she’s in it in other ways that I don’t yet know how to articulate, because this work is so new to me that I am still learning about it. I’m not sure I can nail down specific things. It’s maybe too soon to do that. But the premiere at Lincoln Center was the first time that Erin had seen it. It was a very interesting experience, with the press screening happening 10 days beforehand, and all these people seeing it and talking about it and some stuff going online, which Erin read before seeing the movie. I then sat next to her and felt some of her reactions. I was watching the movie, but I was also highly aware of her on my left responding… recognizing certain things. That was a powerful experience for me—to have, in a way, made this work for her, and then to have her receive it. It was the giving of a gift. And it’s not the first gift of cinema I’ve given her. I was thinking about our wedding and that film as well.

Happily, she had a very good experience of the work at the screening. Afterwards we went to Café Luxembourg, where we had had our first date, with a big group of people, and then we went just the two of us and sat in a little pizza café and talked for two hours about the movie and the screening. It was tremendously important to get that space for just the two of us and talk about what had happened. It was rewarding for me to have her response. And she is an amazing viewer.

What does contingency mean to you?

That’s where the movie starts, with that text: “The idea is one of contingency.” One has to make choices. One can’t live every life or do everything. I’d like to think that if we make careful choices, then our decisions in the life we do lead might redeem or recognize the lives we did not lead. As the film’s text also says, “What tenderness of attention might mitigate battered experience.”

The Extravagant Shadows feels like a major experience in my life. It’s coming at an important moment, in which I’ve just been honored with a “mid-career” retrospective [“Texts of Light: A Mid-Career Retrospective of Fourteen Films by David Gatten,” curated by Chris Stults and organized by the Wexner Center for the Arts] that traveled around the U.S. in 2011 and 2012. I had a year to think about what I have been able to do so far. What is my cinema at the mid-career? I feel a sense of peace right now with having made a contribution to a conversation that I care deeply about, and I am very proud, I think, that my contribution has been valued by other people who are also taking part in the discussion. And so I hope that, in any larger consideration of my life, this work will stand out as something that consolidates, while exploring more deeply and in a different fashion, concerns that have been with me since the beginning. I don’t envision it as being a pivot or a shift, but I hope that it is seen as a flowering of seeds that took a long time to come to the surface. Whatever happens next will certainly affect how The Extravagant Shadows is seen in the future. But what happens next I don’t know.

One way that I see the progression of my films is as a narrative. I think that’s why I am able to bounce between completely different kinds of articulation. The Continuous Quantities project, a series of films in which every shot is 29 frames [modeled after Leonardo da Vinci’s division of an hour into 3,000 equal parts], is so vastly different as a way of thinking about montage from The Great Art of Knowing. But it’s all part of a larger narrative or inquiry about the relationship between different systems of representation, language, and image, and about articulating meaning between them. In the end I think it’s all one project.

]]>

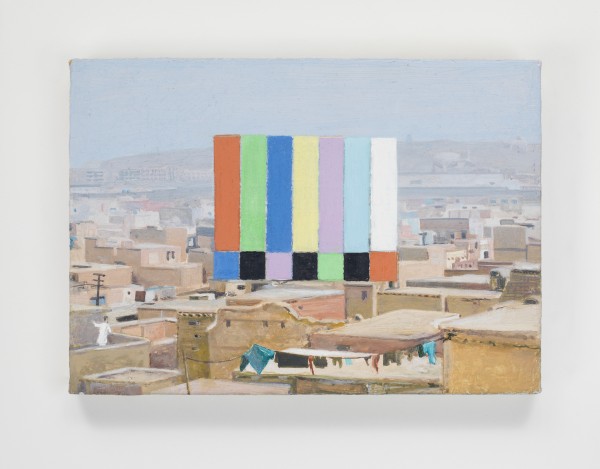

Algiers, from Perret in France and Algeria (2012)

The modernist architect Auguste Perret was born in 1874 and died in 1954. He built houses, studios, churches, and government buildings both in France and in the French colony of Algeria, then died eight months before Algeria declared its war for independence. The German filmmaker Heinz Emigholz’s new film, Perret in France and Algeria (2012), shot on trips to the two countries between March and July of 2011, shows how both sets of buildings are presently being used. In France, a largely Christian country, Perret’s churches and chapels have retained immaculate auras, placing them at a distance from everyday life; in Algeria, which became a Muslim country after winning its independence in 1962, Perret’s Cathedrale d’Oran has been converted into a public library. The air of the French concert hall Salle Cortot, maintaining a division between precisely ordered seats and the performance stage, differs from the availability of Perret’s Algerian Yacht-Club, a crumbling structure turned into a docking space for fishermen’s boats. The film makes it clear that many of Perret’s French buildings are now carefully preserved, oft-deserted performance halls, museums, and official historic sites, while many of his Algerian buildings are in constant public use.

The duality in Perret in France and Algeria—screening in New York February 15 and 16 as the opening film of the Museum of Modern Art series Documentary Fortnight—is communicated through new filmed images of the buildings and the sounds of their surroundings, without voiceover, as befits the usual style of Emigholz. He was born near Bremen in 1948, and began rendering the world artistically as a draftsman before turning to filmmaking. His early films such as Arrowplane (1974) and the Schenec-Tady trilogy (1972-1975) presented, to the tune of scores written before filming, landscapes rendered through sequences of thousands of 16mm photographs. After making a narrative, actor-driven film called The Holy Bunch (1990), he shifted his practice from filming actors in space to focusing exclusively on filming spaces themselves in a series of documentary films.

Over the past 20 years, Emigholz has made more than 80 films in the ongoing nonfiction series Photography and beyond, which uses the tools of filmmaking to present works by visual artists from other mediums, including painting, drawing, sculpture, and interior design. Perret in France and Algeria, which the filmmaker intends as one of the series’ closing films, belongs to a subcategory called Architecture as Autobiography, each of whose entries takes as its starting point the life’s work of a modernist architect or civil engineer. Each film offers a succession of individual sequences containing new images of the person’s buildings in the structures’ chronological order of completion, suggesting both how the artist’s style developed over time as well as how time has impacted his works.

A typical Architecture as Autobiography sequence begins with a title card stating an individual building’s name (e.g., Hôpital Sétif), date of completion (1934), location (Sétif, Algeria), and the date of Emigholz’s filming it (June 22, 2011). The sequence then shows the building through a series of fixed shots of individual parts of it, often taken at slightly skewed angles in keeping with how the human eye frequently looks. For instance, Sullivan’s Banks (2000), a 1995-filmed cataloguing of banks built between 1906 and 1920 by the American architect Louis Sullivan, first presents the exterior of the National Farmer’s Bank in Owatonna, Minnesota as seen from in front of a tree; the film then registers the bank from a series of vantage points along the car-filled streets outside it, glimpsing the neighboring dance school and dry cleaning shop while moving closer to the building, until an old metal sign reading “Office Entrance” appears, transitioning to an exploration of the bank’s interiors.

A similar urge to see informs a trip through Auguste Perret’s Parisian Immeuble d’Habitation de Maurice Lange, as the camera looks first up, then down during a stairwell ascent, finally arriving at a door, and then a trio of moving trees outside. The shots in almost any Architecture as Autobiography sequence link together to form small, self-contained narratives of curiosity, exploration, and discovery, with both eyes and ears taking their fill of a place. Throughout the shots the soundtracks flow richly with ambient noise from both the buildings and their surroundings, whether the dying echoes of human footfalls or the gathering whoosh of wind as it rustles through leaves.

The sound helps the viewer to imagine a greater world of which any one edifice is merely a part. “There is no point in trying to separate a building from its surrounding environment,” Emigholz says in the first scene of his architecture film Schindler’s Houses (2007), an exploration of Los Angeles homes built by the Austrian émigré Rudolph Schindler, with views of the newer curving roads and hilltop houses around them. In that Architecture as Autobiography film, as well as in others, seeing buildings within a greater contemporary urban context suggests how they continue to be relevant to it. In Perret in France and Algeria, regardless of whether the streets surrounding a Perret building are empty, as in Paris, or bustling, as they are throughout Algeria, one is always aware of people continuing to interact with a building regardless of its age, animating it and reinventing its value for the present moment.

These contemporary people include Emigholz, who has made the act of recording other peoples’ life work into his own. As his camera studies interior curving pathways that simultaneously connect and offset the clean, elegant lines of a vertical foundation, it becomes clear that his prized architects’ buildings were made to be inhabited as well as looked at. Their great beauty, his films suggest, holds practical value: it makes inhabiting them a pleasure.

How did you arrive at Perret in France and Algeria?

Between 1986 and 1990 I produced and directed a feature film called The Holy Bunch. It dealt with a group of artists, one of them dying, as well as with an elaborate set of architectures and complicated spaces, designed on a set and filmed in reality at places like at the Cologne Cathedral and La Sagrada Famila in Barcelona. I like to depict complicated, multi-layered spaces. I went broke with The Holy Bunch because I produced it myself, and was sitting with a lot of debt. So I decided to drop the actors and continue with what I liked most. I continued filming the spaces without them.

I made a list of architects and civil engineers whose work I admired: Louis Sullivan (1856-1924), Robert Maillart (1872-1940), Rudolph Schindler (1887-1953), Bruce Goff (1904-1982), Adolf Loos (1870-1933), Pier Luigi Nervi (1891-1979), and Auguste Perret, among others. In 1992 I started preparing one film, a documentary with voice-over, about these architects, their concepts of space, and my thoughts on it all. I filmed and filmed without knowing how I would edit the material. Then, around 1997, I decided to drop the overview approach.

The reason for this was that I thought cinema had lost its purpose as something that could explain the world on every level, as in a Gesamtkunstwerk [“total work of art”]. The Internet arose to provide a lot of information, so now I did not have to infest my film with that information any longer. I could spare the time and present spaces in an act of cinematography instead. Not to dramatize the material, not to put music or anything on top of it. Just to film and represent the spaces in a well-equipped screening room.

It was clear that I had too much material for one film with the works of these guys. I broke the project into several films and made a chronological order for each, a kind of catalogue of the buildings. I would edit the buildings in the order they were built so that we could see how each architect’s work developed over time. I would film the spaces, and in between the images of buildings I would include title cards with basic information: the name of the building, its location, the year it was built, and when I filmed it. My idea seemed so simple that I thought there would already exist hundreds of similar films, but I was shocked to discover that there were none. Our current historical moment’s belief that everything is available to you with the click of a button in a search machine is so utterly false. You have to make long journeys to record these spaces, and nobody had done it before.

The first three short films in the series Photography and beyond premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival in 2001. Some people said, “This is only for architects,” but I had another vision. We all have to live in some kind of building, so everybody has to think about or is confronted with what architecture is or could be, even if one doesn’t want to deal with it. I initially filmed in 35mm because of its high resolution. It was the best stock for documenting architecture. When you work in 16mm you cheat the spaces, the volume of negative space does not show – a high resolution is essential for showing it. Now we work with the RED digital camera and its high resolution, which is a relief, because we couldn’t make certain films on 35mm analogue film stock. On this recent trip we did around the world for The Airstrip, for instance, it would have been impossible to carry that equipment around. But regardless of digital versus analogue, the aim was always, from the beginning, to use the cinema space to represent architecture. This is subversive, because cinema is usually built to show something that takes place within a space, but cinema can represent spaces themselves in the best way that you can think of.

Now there are about eighty films in the series, including nine feature-length works. Perret in France and Algeria is the second-to-last film of a final group of films I call Decampment of Modernism. The first one, Parabeton – Pier Luigi Nervi and Roman Concrete (2012), premiered at Berlin last year and has not yet been released in the United States. The final one, The Airstrip, will be finished this June. Like Parabeton, which deals with both modern and ancient constructions by placing the architectures of Nervi’s modernist buildings in relation to ancient Roman structures the Perret film contains a dichotomy. The Airstrip is a compilation film, and it will sum up my endeavor with conclusions on a worldwide level.

How do you see the paths of Perret’s French and Algerian buildings diverging after Algerian independence?

I knew that Perret had built in Algeria, but I had never been there, so the trip to Algeria and the difficulties of filming there became a story in itself. The buildings there were built under French rule, then Algeria became independent, and it was moving to see what had happened to the buildings there versus those in France and how history had divided their histories into two separate tracks. I like that duality in this film very much. He built one building there, and then maybe three in France and one in Algeria. But I didn’t push their succession dramaturgically—it’s just chronological. It’s not a rhythm I created, it is created by the works themselves.

I do not say, in either case, “This is good” or “This is bad.” First, as a documentary filmmaker, I go to these spaces to record them. I don’t re-arrange furniture; I do not add artificial light; I film everything like it is. Sometimes I’m asked why so few people appear onscreen, to which I say it’s because I don’t use actors. We filmed some small streets in Paris, which were often empty. What can you do? I don’t want to make people act out living somewhere. If they feel comfortable with being in the picture, I feel comfortable with it, but either they are there or they are not. And I must say I am quite happy that they are sometimes absent, because actors can block the view of the real thing. You don’t need somebody to represent you in the picture as an onlooker—you can imagine that you are there yourself.

Perret built some artists’ studios in Paris, including one for the sculptor Chana Orloff in 1929. The Nazis destroyed her studio during WWII, and she died in Israel in 1968. Her son turned her former studio space into a kind of museum for her sculptures, which it remains today. He let us in—it’s not open to the public, but we wanted to film the building. And I was suddenly interested in her sculptures. The result is a long sequence that doesn’t deal much with architecture, because it’s a relatively simple space, but with a full sculptural population. At the end of it appears her bust of Auguste Perret’s head. I love that sequence because, no, people are not technically living there, but in a way they are—the spirits of people who once lived.

Our most populated Paris scene will be in The Airstrip. Perret designed a monument for Gustave Eiffel, who built the Eiffel Tower, which is located at the Tower’s north corner. There are a lot of people in that sequence, standing in line. But it’s generally true that in Paris there are empty streets and in Algiers there are populated streets. In Algeria, when you see the Maison de l’Agriculture, you also see hundreds and hundreds of people walking outside it. And then you see something like the Yacht Club in Algiers. If a yacht club by Perret would still exist in the so-called West, it would be posh. In Algiers, the Yacht Club is now a run-down space for fishermen to use. I’m not moralistic about what happens—I just want to show it. But for me that run-down place is a much nicer yacht club than its posh counterpart in the West could ever be.

It seems that some cultures use up their architecture. East Germany used up the DDR, sometimes destroying old quarters and building new ones. We don’t live in a museum. Different societies deal differently with architectural heritage. It’s not up to me to say what the Algerians do with their buildings is wrong and what the French do is right, or the other way around. But we can read. When we depict what’s there, I think we can very well read what’s going on.

What happens to modern buildings in time? The originators, the first owners, leave them. New people move in, and the buildings change. Some become so-called trophy houses, or masterworks. Many buildings by Schindler, Maillart, and Goff were originally single custom-made houses, built cheaply, but to renovate or even simply maintain them now would be very expensive. Labor was cheap when they were built, but now it is expensive in certain countries. In the case of Robert Maillart, the scaffolding for the buildings was cheap. The buildings were elegant concrete structures, and the scaffoldings were masterworks in themselves. But now you can’t just go to Home Depot to fix a Schindler building. If you would try to redo them now, you couldn’t pay for it. A lot of the buildings I have depicted are already forgotten, with only one building per architect taken to be the essence of his work. People rarely take the whole arc of his work, but I want to show how it began and how it ended.

The way I see that arc also changes over time. When Sullivan’s Banks was being made, many things in it were banal. But when I look at it now I see it as a documentary film about 1995, capturing things that don’t exist anymore. Goff in the Desert (2003) contains houses that were destroyed by Hurricane Katrina, as well as by other hurricanes and tornados in the American Midwest. These films work first as records, then later as monuments, both to the buildings and to their makers.

Some of these guys, like Bruce Goff and Rudolph Schindler, were always in the middle of controversy. The architectural community didn’t like them. Goff and Schindler were expelled from the International Style movement because their views were not presumed to be politically correct. They had a lot of problems with the building establishment, so they only built small household units. They never got into big business. When you make films like these about these neglected architects, you not only join a discussion, but you create an argument. However much people want to talk about what’s good or bad in architecture, when you’re faced with a 105-minute 35mm film of Goff’s buildings, you can’t just do like Mies van der Rohe did and say he built crap. You cannot talk it away anymore—you have to look. And in fact what I like about Bruce Goff’s work is how present it feels.

How do you prepare to film buildings?

It starts with me accidentally running into something. I ran into Schindler buildings in Los Angeles in the 1980s. I didn’t even know his name, but I remembered a certain space later. In Goff’s case, too, I went into a house by him in Los Angeles. I had no idea who he was, but I remembered the house suddenly when I decided to do an architecture film. I remembered other spaces suddenly, then started researching, then at a certain point looked at images and decided to travel to their sites. In 1991 I went into a bookshop in Venice, California, and found a book with photographs of Louis Sullivan’s banks. At that point I was thinking a lot about modernity and the ornament and the free-hanging façade, rather than a façade that carries a building. That has been possible in modern architecture since the end of the 19th century. As the façade doesn’t carry something, the possibility exists of doing free design on it. Louis Sullivan worked a lot with these new possibilities. The book addressed my own interests, and I thought, “I have to go there. I can’t rely on these photographs. I have to see it myself.”