Installation view of ‘There’s so much I want to say to you.’ Photograph by Sheldan C. Collins.

It is an appropriate moment for Sharon Hayes’s solo exhibition There’s So Much I Want to Say to You, a year when modes of “public address” — the framework that has anchored her work for the past decade — have come to the fore. Her work often employs the “official” language of politics (campaign slogans, speeches), on the one hand, and that of protest on the other, two conceptions of the public and the political that are at once inextricably linked and diametrically opposed. With the convergence of an election year and the widespread Occupy protests — whose own slogans have quickly become a part of the vernacular — in 2012, an examination of political speech seems apropos, even necessary.

In spite of the timeliness of her current exhibition, Hayes’s practice is rarely about a specific event in itself. Rather, her work — which she describes as “speech acts” — is largely concerned with historical memory as explored through the lens of the language of politics, emphasizing the points of continuity and change. As Hayes notes in an artist’s statement, her work conceives of the political present as one that is “always allegorical, a moment that reaches simultaneously backwards and forward.”

In lieu of multiple galleries with labels delineating discrete works, the exhibition takes the form of a single, large-scale multimedia installation spanning the entirety of the Whitney’s third floor. Much of the space is taken over by a large-scale plywood platform throughout which she has placed various video, audio, and photo-based works, several of which were created specifically for the show. Designed in collaboration with artist Andrea Geyer, the platform was meant, according to the two, to recall a trade show or rally — temporary, ad hoc structures where various attractions and voices compete for attention, intended to counter the assumed sterility of the museum setting and its impression of quiet refinement. Viewers must move around and throughout Hayes and Geyer’s installation to see everything: several works are tucked into corners, or given their own small, semi-intimate nooks for sitting and watching projections or listening to audio pieces.

Sharon Hayes’ ‘Everything Else Has Failed! Don’t You Think It’s Time For Love?,’ 2007. Photograph by Andrea Geyer. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Leighton Gallery, Berlin.

Yet, the apparent nod to interactivity seems overstated: despite the somewhat nontraditional arrangement, sitting in a gallery with headphones on is hardly a radical form of engagement, nor a democratization of the gallery space. In spite being rooted in the public sphere, Hayes’s work does not necessarily lend itself to participation, although the process of creating is often collaborative: her strongest works are those that most directly address the intersections between the personal and the political, in which she is directly present, addressing her audience in the first person. While the material she probes harks back to identity politics — gay liberation, AIDS activism, the women’s movement, Black Power — the “I” in her work can never be directly identified as the artist herself. Hayes is not concerned with an examination of her own individual identity or subjective experience, and many of the events she references are pulled from well before the artist reached maturity, in some cases before she was even born. Rather, the dissonance between the words themselves and the person who speaks them, or between the urgency of the messages of past moments and their evocation in the present, serves to disrupt the continuity of historical memory, forcing viewers to consider the language itself, divorced from its familiar contexts.

In the audio installations Everything Else Has Failed! Don’t You Think It’s Time for Love? (2007) and I March in the Parade of Liberty, But As Long As I Love You I am Not Free (2007-08), both of which originated as public performances, Hayes delivers first-person love letters that merge the language of political protest with that of individual desire. The former was initially delivered outside the corporate headquarters of UBS, addressed to an unnamed lover from whom the author had been separated; the latter employed gay liberation slogans alongside fragments from sources such as Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis and newspaper coverage of early gay rights protests. Intentionally conflating public and private by delivering ostensibly “personal” correspondence in the streets, she highlights the uneasy divide between the two spheres, particularly concerning gay and women’s rights, in which the most intimate aspects of one’s life are points of political contention. Desire is recoded as a political category, embodied by the demands of protest.

This intersection between performance and speech is plainly Hayes’s strength, and the works in which she is most absent also tend to be the exhibition’s weakest: an overhead projector beams a still image of the face of notorious homophobe Anita Bryant covered in cream pie, the result of a protest by gay activists, or a selection of found “before” photographs, framed and placed on a wall within the installation, meant to — according to a pamphlet at the exhibition’s entrance — metaphorically chart the progression of a suburban housewife into a radical activist. Arrangements of decades-worth of record covers lining the gallery’s perimeter, all from the artist’s personal collection, provides notable insight into her process and influences, but does little as a work of art in itself. Likewise, Join Us, a wall-sized grid of political flyers announcing protests and public actions, from the Vietnam War-era to Occupy Wall Street, forms a fascinating document of the history of American dissent, but its appeal is derived the power of the material itself, not Hayes’s treatment of it. Such moments left the impression that Hayes, for her most significant exhibition to date, felt compelled to fill the space: to give her audience something to look at. Indeed, in spite of her apparent desire to subvert the traditional museum exhibition format, these static, wall-bound pieces seemed most aligned with traditional gallery fare. They pale in comparison to Hayes’s arresting performance-based projects, whose impact is largely drawn from what is said rather than what is seen.

Hayes’ ‘Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) Screeds #13, 16, 20 & 29,’ 2003. Installation detail. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Leighton Gallery, Berlin.

The exhibition’s obvious high point is one such work, a small sub-room within the installation, playing Hayes’s Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) Screeds #13, 16, 20, & 29 (2003), one at a time. In them, we see a close-up of the artist’s face, staring directly at the camera against a plain white wall, as she attempts to recite the transcripts of tapes sent by Patty Hearst to her parents while kidnapped by the SLA. The charged language of the screeds, political demands and denunciations interspersed with a daughter’s distress at her family’s apparent disregard for her circumstances, is abstracted in the videos, as Hayes stumbles over the words, visibly struggling to recall her lines. She is assisted by a group of people offscreen who correct her when she makes mistakes, jarring interruptions that prevent any notion of identifying the speaker we see — Hayes — with the author of the communiqué she delivers. Elsewhere, Hayes has displayed this piece as an installation, surrounded by piles of black VHS tapes for the visitor to take, but the intimacy of the presentation here works in its favor; the room created for the SLA Screeds is tight, claustrophobic even, with the viewer confronted directly with the artist’s face, wincing as she butchers the text.

Hayes’s notion of her work as “speech acts” is, of course, a reference to the work of linguist J.L. Austen, whose How to Do Things With Words argued that certain forms of language — what he termed “performative utterances” — had the capacity to not only articulate or describe, but to enact, as in an officiant who marries a couple or a judge who delivers a prison sentence. In Hayes’s work, the idea of “speech acts” takes on a twofold meaning: she calls attention to the potential of language in its ability to shape the social and political landscape, but also uses language actively, temporarily recalling past moments through her performance of their linguistic traces.

‘Sharon Hayes: There’s So Much I Want to Say to You’ runs at the Whitney Museum of American Art, 945 Madison Avenue, through September 9.

]]>

How Should a Person Be?

Sheila Heti.Henry Holt and Co., 2012.

Writing on the French artist Sophie Calle’s True Stories (or Autobiographies), the art historian Rosalind Krauss asked, “Under what circumstances are stories true?” An ongoing project begun in 1988, True Stories is comprised of autobiographical texts narrating significant moments in Calle’s life, juxtaposed with quasi-anthropological photographs of related objects (and more recently, with the objects themselves). Drawn from the artist’s memories, fantasies, and dreams, Calle’s stories are true to the extent that she has claimed them as her own. Yet, taken as a whole, these ‘truthful’ fragments form an unwieldy composite portrait that can neither be considered wholly accurate, nor entirely fictional — a work of art is always, on some level, constructed, even if cast entirely from life.

In the recently released US version of Toronto-based writer Sheila Heti’s novel How Should a Person Be?, a revised edition of the novel she published in Canada in 2011, there is a disclaimer in small print at the bottom of the colophon:

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel either are products of the author’s imagination are used fictitiously.

Billed as “a novel from life,” How Should a Person Be?’s protagonist is a recently divorced twenty-something writer named Sheila, whose biography conforms more or less exactly to that of the author. Much of the book focuses on the relationship between Sheila and her best friend, a painter named Margaux, who is likewise modeled on Heti’s real-life best friend, the painter Margaux Williamson. The majority of the characters are similarly recognizable as members of Toronto’s art and literary scenes. Large portions of the novel take the form of emails and transcripts of conversations recorded by Heti, ostensibly reproducing her own words, as well as those of Margaux and others, verbatim. That a novel consists of fictitious characters, organizations, and events would normally seem self-evident, but in How Should a Person Be? such a categorization becomes somewhat more ambiguous. Under what circumstances are stories fictional, if the people, places, and events they depict might equally be recognized as fact?

When asked about the difference between herself and the character Sheila of the novel, Heti answered: “I’m a person and not a piece of paper…A person is not a static thing, or a bunch of words.” The novel calls attention to this distinction throughout, directly addressing the tension implicit in creating a “novel from life.” Heti does not merely use her repository of recorded and transcribed material as the model for the book, but foregrounds the process of collecting it, narrating the novel’s own formation: Sheila begins taping her conversations because she is struggling to write. Commissioned by a feminist theatre company to write a play about women — a subject she professes to know nothing about — she hopes that analyzing her own real-life dialogue will provide insight into how to give her characters weight. Though the play is the pretense for her obsessive documentation, Sheila’s inquiry soon takes on a life of its own. Realizing, after a trip to Miami with Margaux for Art Basel, that her research into the lives of those around her is more interesting than the fictional people she’s been attempting to make lifelike, Sheila begins transcribing the recordings, along with her own recollections of events: “It wasn’t my play, but it felt good….I felt closer to knowing something about reality, closer to some truth.”

It seems significant that Calle’s work looms large in How Should a Person Be?’s most obvious literary precursor, Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick, a novel in which the author similarly mines her own life, leaving proper names in tact (I Love Dick also narrates its own formation). Equal parts confessional and analytical, Calle’s work seems to be the conceptual forbear for Heti’s novel. Through a practice that turns a documentary lens to the artist’s own subjective experiences, Calle’s life is not only her source material, but her medium: she documents her actions, but also acts so that she can document.

For Krauss, the structural principle guiding Calle’s work — what she calls its “technical support” — is photojournalism, a kind of forensic research into her own life, as well as the lives of those she encounters: for The Address Book (1983), Calle photocopied the contents of an address book she found on the street and reached out to the contacts listed within, inquiring about the owner’s character, interests, and routine, ultimately publishing the results of her investigation in the French newspaper Libération. Likewise, Heti cannibalizes the words of her friends, transforming those around her into subjects.

When the owner of Calle’s address book caught on to the project, he retaliated by publishing a nude photograph of her in the same newspaper, an attempt to match his own feelings of violation. In the novel, Heti’s subjects also push back against her treatment. Though they consent to being recorded — as Margaux states, “You know I have more respect for your art than I do for my own fears” — Sheila’s transformation of their friendship into an object of study is a constant source of tension: “I’m doing a lot, what with letting you tape me, but — boundaries, Sheila. Barriers. We need them. They let you love someone. Otherwise you might kill them.”

As Calle noted in an interview with Heti in The Believer, where the latter is, appropriately, the Interviews Editor, the question of truth in art is never straightforward:

The truth? Which truth? Your truth? Their truth? The truth today at two o’clock in New York, or the truth tomorrow at five o’clock in Paris? The truth now that it’s raining? What does it mean? Me, I would say things happened or didn’t happen, but I would not say that’s the truth.

This shifting definition of “truth” seems equally applicable to Heti’s novel. Though she insists upon the distinction between its characters and the actual people whose lives she borrows — a person is not a piece of paper — it is impossible to divorce the two entirely, as Heti surely understood when she chose not to assign her friend-characters new names. Heti has regularly cited the influence of reality television shows on How Should a Person Be?, particularly docudramas like MTV’s The Hills. The comparison is apt, at least on the level of form: we can say conclusively that the events depicted are real to the extent that they happened, and someone recorded it, but the final product is artificial — fiction composed from fragments of life.

]]>

"Triangle," 1979. courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Is it more surprising that Croatian artist Sanja Iveković has never had a major exhibition of her work in the United States until now, or that this overdue retrospective is taking place at MoMA? Iveković’s work is overtly political, incisively tackling issues of women’s rights, life under dictatorship, East-West relations, and the political struggles in the countries of the former Yugoslavian federation, both during and after Communism. Moreover, it defies easy categorization in terms of medium and style: though the exhibition, Sweet Violence, is presented under the aegis of MoMA’s Department of Photography, the work on display ranges from photo-based conceptual projects to collage, drawings, performance, video, and installation. Iveković has exhibited widely in Europe, and is considered a crucial figure in post-war Eastern and Central European art, yet she is little-known in the United States, an art historical blind-spot this retrospective aims to correct.

In the exhibition catalogue — which, curiously, contains an essay by noted Marxist literary theorist Terry Eagleton — the show’s curator Roxana Marcoci charts the history of Yugoslavian art from 1945 to the near-present, contextualizing Iveković’s practice in terms of both the historical and political circumstances under which she worked and her artistic predecessors, but also her significant influence on a younger generation of artists from former Yugoslavian countries. As Marcoci points out, Iveković was among the only women involved with the “New Art Practice,” a loose network of Yugoslavian artists in the late-1960s and 1970s who rejected the style of officially sanctioned art in favor of alternative modes of production and distribution; moreover, Iveković is often credited as the first Yugoslavian artist to explicitly identify herself as a feminist, what she describes as “a gesture of disobedience toward the communist regime that treated feminism as a bourgeois import from the West.” Comprising four decades of her work, Sweet Violence reflects Iveković’s ongoing commitment to an activist practice, one that challenges authority and questions the ways in which dominant narratives are formed and disseminated.

For Trokut (Triangle) (1979), represented here by photographic documentation, Iveković directly intervened into the systems of repression, surveillance, and control governing Yugoslavian society, a gesture of resistance that acutely merges the personal and the political. During a visit by Yugoslav president Marshal Josep Broz Tito, Iveković stepped out onto the balcony of her Zagreb apartment, which overlooked the presidential motorcade’s route through the city, with a glass of whiskey and a stack of foreign books — including the British Marxist sociologist Tom Bottomore’s 1964 study Elites and Society — and mimed masturbation, knowing that she was being watched by members of the secret police on the roof of the opposite building. After eighteen minutes, a policeman came to the door and ordered her off the balcony, completing the performance. Trokut not only illustrates — and comically challenges — the culture of control under which Yugoslav citizens were living during Tito’s reign, but also inverts it, making the members of the secret police complicit in her work: they play directly into her expectations, unwittingly performing the role she has assigned them.

"Sweet Violence," 1974. courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Likewise, the exhibition’s titular work, Sweet Violence (1974), addresses state propaganda in Tito’s Yugoslavia through the appropriation of broadcasts on state television. Placing black bars on her television monitor, Iveković taped a daily broadcast of a propagandistic program on Zagreb’s economy, a gesture that both obscures the image, functioning as a kind of Brechtian distancing effect that refuses the viewer the possibility of being “seduced” by the media’s message, and also metaphorically reflects life under the regime, the vertical strips recalling those of a prison cell. Indeed, it is this interest in the media that forms one of the most consistent strands throughout her entire oeuvre: the majority of works in Sweet Violence make use of appropriated and altered mass-media imagery, detourning these images to highlight the ways the media is used as a tool by those in power. As Iveković noted in a 2009 interview, “The media’s role in shaping dominant cultural representations should never be underestimated…I appropriate media images because my intention is to subvert the assumptions implied in the discourse of mass media using its own language.”

In addition to government propaganda, much of her work employs imagery drawn from or based on fashion magazines and advertisements, specifically considering the media’s role in the subjugation and manipulation of women. This is perhaps most clear in the series Women’s House (Sunglasses) (2002–09), lining the entrance to the exhibition, for which Iveković superimposed first-person accounts from women living in domestic violence shelters over advertisements for designer sunglasses, creating a stark contrast between the glossy imagery of fashion photography, which aims to seduce women into purchasing luxury goods, and the brutality of the narratives of abuse. Referencing the dark glasses often worn by abused women to hide their bruises, the models in these advertisements become stand-ins for the battered women, a reminder of not only the societal pressures faced by women, but also the complex entanglement between consumerism and exploitation.

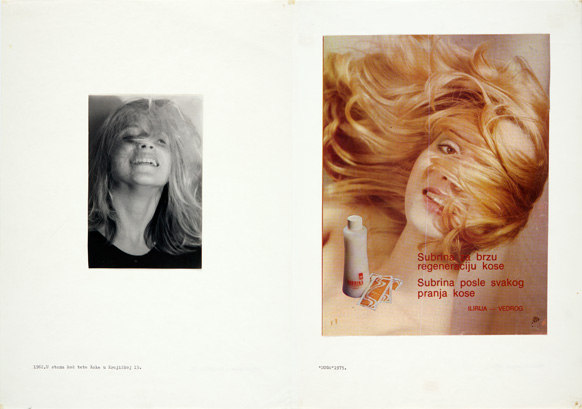

Similarly, in the earlier series Double Life (1975–76), Iveković juxtaposed advertisements for products targeted towards women, such as cosmetics and cookware, from various international women’s magazines, with photographs of herself taken between 1953 and 1976. Though Iveković and the model appear in nearly identical poses in each pair, the majority of the snapshots of the artist were in fact taken prior to the publication of its pendant image, suggesting that these media-circulated tropes of femininity are so deeply ingrained that women embody them unconsciously. Presenting dozens of these images — advertisements from different countries and years, each hawking different products — together, Iveković highlights the uniformity of female media roles, and the unsettling ways that they are internalized and replicated.

"In Aunt Koka's Apartment, Krajiška 19, 1962 / "Duga," 1975. courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

While her earlier work from the 1970s and early 1980s often responds directly to life under dictatorship and the hypocrisies of state socialism — as Marcoci notes in the catalogue, the official egalitarian rhetoric of Communism, which purportedly made feminism obsolete, clashed with the reality of life as a woman in what Iveković refers to as a patriarchal culture — more recent projects, created after the fall of Communism and the break-up of Yugoslavia, often address questions of cultural memory and the ongoing struggles of women worldwide to achieve equality under democracy.

The project Pregnant Memory, intended for the 1998 Manifesta biennial in Luxembourg, was a proposal — ultimately rejected — to alter Luxembourg’s famous World War I and II memorial, “Gelle Fra” (Golden Woman), an obelisk in the center of Luxembourg’s capital topped with a gilded neoclassical statue of Nike, by removing the statue from the memorial and placing it at a women’s shelter for the duration of the exhibition. Commissioned, in 2001, to create a work for another exhibition in Luxembourg, organized by the Casino Luxembourg and the Musée d’Histoire de la Ville de Luxembourg, Iveković presented a new version of her Manifesta proposal, Lady Rosa of Luxembourg, an altered replica of the Gelle Fra placed near the original monument, replacing the its allegorical image of victory with a gilded pregnant figure and dedicating it to the radical German Marxist Rosa Luxemburg. In creating a new version of the memorial, Iveković points to what is concealed by the original: though women were actively involved in Luxembourg’s resistance movement during World War II, their contributions are rarely, if ever acknowledged; instead, the place of women within official commemorations are as allegorical representations.

The project was the subject of enormous controversy, receiving international attention and provoking heated comment from supporters and detractors alike worldwide. Presented in MoMA’s atrium, the towering statue is surrounded by an installation documenting the work’s reception, including vitrines full of newspaper clippings and magazine articles from across the globe, as well as monitors with recordings of television broadcasts discussing the piece. Iveković appropriates the outrage, incorporating it into her work as a comment on the public’s discomfort with a woman who dares to challenge symbols of heroism and national pride, as well as a reflection of her career-long interest in the power of the media to shape and manipulate public opinion.

Further, she has considered the media’s complicity in the erasure of history, particularly focusing on the legacy of Communism in the former Soviet bloc. Much as Lady Rosa of Luxembourg addresses the establishment of a national narrative of heroism that ignores women’s involvement, works such as the series Gen XX (1997–2001), Rohrbach Living Memorial (2005), and The Right One. Pearls of Revolution (2010) all highlight the aspects of the region’s history that have been suppressed, countering what she sees as Croatia’s cultural amnesia; in its eager embrace of neo-liberalism after achieving independence from Yugoslavia, the nation was quick to abandon the remnants of its socialist past.

For Gen XX, Iveković altered images of fashion ads featuring well-known supermodels, replacing the ad’s corporate logo with information about forgotten socialist heroines, women who had been imprisoned, tortured, or executed for their resistance to Croatia’s Nazi-controlled fascist government in the 1940s — including the artist’s mother, Nera Šafarič, a fighter in the People’s Liberation War who was arrested and sent to Auschwitz in 1942. Lamenting the fact that these women’s stories have disappeared from national consciousness in the post-communist period, Iveković’s juxtaposition of the ubiquitous faces of the models with the now-obscure names of the female militants is a damning commentary on the ease with which Croatia has forgotten the women who helped to shape its history — and the fashion industry’s constant emphasis on the new. Iveković distributed the work as mock advertisements in the Croatian alternative magazine Arkzin — no mainstream publications would print them — inserting them directly into the system she critiques.

Indeed, one of the difficulties in staging a museum exhibition of Iveković’s work is that much of it has taken place outside of an institutional setting: in addition to public art projects like Lady Rosa of Luxembourg, she has often presented her work in the form of billboards, posters, public television broadcasts, and publications, reflecting her interest in maintaining an artistic practice that directly intervenes into the surrounding world, in which the aesthetic operates in tandem with the political. In her approach to curating this exhibition, Marcoci seems to have acknowledged the limitations of the museum, supplementing Iveković’s work with contextualizing labels and, in some cases, showing projects in multiple formats: Gen XX is displayed both as large-format wall-mounted prints and in vitrines containing issues of Arkzin, showing the project as it originally appeared.

Turkish Report (2009) at the 11th Istanbul Biennial. Collection the artist. Courtesy Amnesty International USA.

Moreover, the exhibition aims to activate viewers through disrupting certain conventions of museum behavior. Strewn throughout MoMA’s photography galleries are crumpled balls of red paper, their haphazard placement and crude handling in marked contrast to the pristine rooms and deliberate installations seen throughout the rest of the building. Visitors seemed unsure of what to do with this apparent detritus: most treated it with a kind of bewildered reverence, traversing the galleries carefully as to avoid hitting the discarded sheets, occasionally stopping for a moment to glance at one contemplatively, while others gave them a dismissive kick, taking a certain satisfaction from the fact that no one attempted to intervene.

After receiving an approving nod from a museum guard, I picked one up and opened it, revealing a printout of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), an agreement adopted by the United Nations in 1979 that has been ratified by virtually all its members, but — as a wall label in the exhibition’s final room points out — not the United States (fellow dissenting countries include Iran and the Sudan.) The installation, titled Report on CEDAW U.S.A. (2011), is, in a sense, the exhibition’s most subtle work, apt to be overlooked by most visitors, but also its boldest statement, transforming what has been called a “bill of rights” for women into literal garbage. As Iveković states, “The position of an artist differs from that of an activist, but rather than separating the two activities, we can see them as circles of human activity that overlap in a relatively small area, and that is the area in which I try to do most of my work.”

Sanja Iveković’s “Sweet Violence” is on view through March 26 at the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53rd Street New York, NY 10019.

]]>

Michael Riedel 's installation for David Zwirner. Image by Rachel Wetzler.

For his Cartier Award commission at the 2010 Frieze Art Fair, British artist Simon Fujiwara created the installation Frozen, a mock-archaeological dig revealing an ancient lost city found underneath the site of the fair. Remnants of what he dubbed “The Frozen City” were spread throughout the its grounds at Regent’s Park — the home of a patrician patroness of the arts; a brothel; a refectory specializing in the city’s delicacy — human flesh; the tomb of a young artist who met an untimely death under suspicious circumstances; the Macellum, the city’s art market, sardonically described as “the most important public space in the city” — each alluding to the decadence of the environment. Walking around this year’s Armory Show, I couldn’t help but think of Fujiwara’s installation, wondering what conclusions some hypothetical anthropologist of the future might draw from the fair and its mixed cues, were she or he to stumble upon its ruins.

For one, what to make of all the objects? Looking around the fair, one would be hard-pressed to find evidence of the participatory, socially engaged, project-based practices that have dominated in recent years. This comes as no surprise — it’s hard to hang a performance over your sofa — but it speaks to what feels like an increasing gulf between the art world of the fairs and the art world at large. The newly-inaugurated “Armory Performance” series was a weak nod in this direction, though of the four programs, two of them could only be seen on Wednesday during the VIP preview. Based on fair ubiquity alone, the unacquainted might think that Julian Opie and Fernando Botero were our culture’s most prized artists, even though the work of such artists is trotted out from the depths of gallery inventories for the fairs, never to be seen again during the rest of the year. Painting reigns again, briefly. Though it returned, this year, with forty-six fewer booths than last, the Armory Show still feels endless; each gallery’s offerings start to look alike.

Further, how to respond to booths that aimed to critique the fair’s milieu? At Winkleman Gallery, a cardboard cutout of artist Jennifer Dalton holding a cocktail stood in front of a blown-up photograph of an exclusive gala; the gallery offered a limited edition shopping bag to any collector willing to give up his or her Armory VIP card, a riff on Dalton’s series The Collector-ibles (2006), miniature figurines of big-name art collectors proffering shopping bags labelled with the type of art they tend to collect — “Contemporary,” “Asian Art,” “Old Masters,” and so on. Giving over the booth to a critique of fair culture seemed like a bold move until I asked a representative of gallery if they had anything for sale — they did, of course. It’s hard not to read such a gesture as more gimmick than incisive critique. Pointing out that an art fair caters to the wealthy — that it is more shopping mall than exhibition space — is so obvious that it barely needs stating. A more interesting take might have been an acknowledgement by both artist and dealer that the fairs have become a necessary evil for those trying to stay afloat, that a successful Armory Week can put a gallery in the black for the year, enabling a more ambitious, but perhaps less commercially viable, program.

This lack of self-awareness was seen even more acutely in the booth of Modern Magazine at Pier 92, given over to SoHo’s Cristina Grajales Gallery, which specializes in design. Placed under a garish chandelier, with no sense of irony whatsoever, were a series of wall-hangings-cum-chairs by Chilean artist Sebastian Errazuriz bearing slogans culled from Occupy Wall Street signs. The gallerist waxed on about the artist’s avowed interest in Occupy Wall Street and his sympathy for the occupiers: the idea behind the series was that the words of the 99% printed on the chairs, once purchased by collectors, would “occupy” the homes of the 1%, at $2,500 apiece. The project was so woefully misguided that it hardly seemed worthwhile to point out the dubious ethics of co-opting such slogans at all, let alone to offer them for sale at an event devoted to unbridled commerce.

The Armory’s “Open Forum” series of talks offered its own set of perplexing contradictions: a panel on Situationist Asger Jorn; more than one on art, class, and social change, with titles like “Enduring Utopias” and “The Efficacy of Art to Incite Social Change”; another on alternative, non-commercial spaces, featuring Brooklyn’s Cleopatra’s and Copenhagen’s IMO — all worthwhile topics, to be sure, but how to resolve the content with the context? Walking around Pier 92 one afternoon, I overheard a well-dressed man complaining about the crowds to a dealer at an upmarket London gallery: “Who are all these people?” he asked, with an exasperated tone. “Most of them barely look like they could afford the $20 to get in the door.” Is it possible to have a meaningful discussion about the ability of art to affect social change in the same building as such an exchange? Can we talk about structural inequality in the presence of a VIP lounge?

My favorite display at the Armory was one that embraced, or at least acknowledged, its context: At David Zwirner’s booth, the German artist Michael Riedel papered one wall with a purple-hued photograph of the booth itself, giving the illusion, momentarily, that it had doubled in size. During the vernissage, it was reinstalled in turquoise, a gesture curiously reflective of the workings of the fair: when I returned to the Armory for a second visit once the show had opened to the public, I noticed that several booths had turned over their displays entirely, presumably swapping out work that had already sold on the first day. Also on view at Zwirner were three of Riedel’s “Poster Paintings,” for which the artist reconfigures the text of art world press materials, printed matter, and ephemera — for instance, every mention of his name on the MoMA website; the transcript of his 2011 performance “Time Bank Robbery” — into stark, graphic compositions in InDesign, before silkscreening them on canvas. The work seems less like heavy-handed critique of the art world’s institutions than an investigation into their workings, the garbled text recalling the empty, elliptical language of so many press releases.

Michael Mahalchik's "Bed In." Courtesy of James Wagner.

On the opposite end of the art fair spectrum was the Dependent, a one-day-only affair at a budget hotel on the Lower East Side, featuring some of the more adventurous small galleries and artist-run spaces from New York and farther afield. The atmosphere was decidedly convivial, with several booth attendants found casually lounging on the hotel beds — indeed, Canada staged a recreation of John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s infamous 1969 “Bed In” protesting the Vietnam War — more likely to be chatting with friends and visitors than negotiating the terms of a sale. Artwork covered virtually every available space, displayed on walls, television screens, beds, and bathtubs, with many of the participating artists responding playfully to the setting, as in Michael Bell-Smith’s schlocky photographs of musical instruments at Foxy Production, which were in fact reproductions of stock images from Getty Images purchased by the artist after he saw them in his room during a hotel stay of his own. Less an art fair, in any meaningful sense, than an opportunity for artists and spaces shut out of the Armory frenzy to make themselves visible, it was the one place I visited over the course of the week where the art world seemed more about art than money.

]]>

Tommy Hartung, Anna (video still), 2011, via On Stellar Rays

For his first solo show at the Orchard Street gallery On Stellar Rays, The Ascent of Man (2009), Tommy Hartung created a video inspired by scientist and historian Jacob Bronowski’s 1973 BBC documentary of the same name, which presented a vision of human history as a sweeping narrative of progress from proto-ape to modern civilization. In his second show at the gallery, Hartung once again took on a canonical narrative, albeit of a different kind: Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, often regarded as the greatest novel ever written, the crowning achievement of literary history, and one that is itself fundamentally concerned with notions of progress and social change.

The connection between Hartung’s film Anna and its ostensible subject, however, is hardly straightforward: The novel is less represented in the film than alluded to obliquely, its major themes and symbols torn out and reconstructed into a fragmented display of images. Indeed, the titular character of Anna is absent altogether, reflecting the fact that Hartung’s work is as much about the process of filmmaking as it is social and cultural history. The films are created in the artist’s studio using hand-crafted models and sets, stop-motion animation, low-fi special effects, and appropriated archival footage — in the case of Anna, the 1930 Soviet film Earth, part of director Alexander Dovzhenko’s “Ukraine Trilogy”. It is a process that draws attention to the ways in which a film is constructed, much as its disjointed imagery highlights the equally constructed nature of the large-scale narratives of history and progress that Hartung probes.

If the themes he addresses are often universal and triumphant, they appear, in his films, to be decomposing — literally broken apart through staccato cuts and disorienting effects. The film has no plot to speak of, at least not in any traditional sense; instead, its most appreciable message revolves around the collapse of narrative. The film presents a world in which ideology is shown to be suspect, linearity resisted. Hartung aptly refers to his work as “dead cinema,” pointing not only to the nature of the materials he employs — mannequins instead of human actors, handmade dioramas constructed in the studio that function as sets, archival footage borrowed from the medium’s past — but perhaps also to the much-discussed decline of “grand narratives” proclaimed by Lyotard to be the defining mark of postmodernism.

Tommy Hartung, Anna (video still), 2011, via On Stellar Rays

The ideas that Hartung’s films revolve around are ones that are outmoded, in decline, have failed, or no longer hold any currency. Earth, scenes from which are superimposed over Anna’s stop-motion tableaux, chronicles a fictional Ukrainian peasant insurrection against landowners resisting collectivization, the promise of a new social order in which a community of equals is at one with the land they work. From the vantage of the present, in which Stalinist collectivization policies signal totalitarianism rather than utopia, what was once an image of hope for the future comes to represent the failures of the past — we know how this story ends, after all. Both Anna Karenina and Earth are portrayals of society in the midst of upheaval, in which ideological battles and competing visions of progress come to the fore; as the exhibition’s press release notes, Hartung is concerned precisely with the “paradoxical failure of emancipatory ideologies to serve the needs of ordinary people,” and in his own film this failure seems to be embodied in a resistance to any semblance of a coherent narrative, a challenge to the notion of the forward march of progress.

Hartung’s films constantly call attention to their status as constructed images, refusing the viewer any illusion that they might be visions of reality: the mannequins and sets are crudely assembled, and, to an eye accustomed to the seamless effects of contemporary Hollywood cinema, Hartung’s techniques are plainly — and intentionally — obvious. As if to insist that we acknowledge Anna’s artifice, in the center of the gallery itself Hartung placed an installation composed of the mannequins and props used to create the film, accompanied by a camera track system, highlighting the process of making it by openly displaying the tools that facilitated its creation.

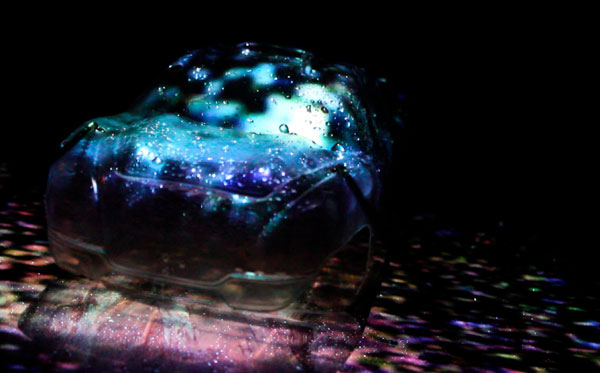

Tommy Hartung, Epilogue (detail), 2011, via On Stellar Rays

Within the gallery, sharing the viewer’s physical space, the mannequins have an unsettling presence: These are not the smooth, perfect plastic bodies of department store displays, but crudely rendered casts, daubed with paint and glitter. More importantly, they are dismembered and hollow, stuffed with candles, pipes, and wires, and surrounded by piles of salt and incense, creating a kind of perverse, uncanny shrine. Indeed, the image of the body-in-pieces carries its own loaded set of associations, both art historical and theoretical, immediately recalling Hans Bellmer’s Surrealist poupées, but also war imagery, with the mannequins’ metal appendages suggesting prosthetic limbs.

And yet foregrounding the means of constructing the film also serves to emphasize Hartung’s role as creator: As opposed to the large-scale operations of mainstream filmmaking, Hartung’s films are essentially one-man productions, in which the artist acts not only as director, but also set designer, cameraman, editor, and, indirectly, actor, as he brings the inanimate mannequins to life. That the films are created in his studio, often employing his own possessions — as part of his installation for MoMA PS1’s “Greater New York” in 2010, Hartung relocated his fish tank to the gallery, pet koi included — only serves to further confuse the boundary between process and product. A member of the gallery’s staff mentioned that Hartung would continue to shoot new footage throughout the run of the show, suggesting that the artist conceives of the project as an open-ended experiment rather than a finished work, itself a gesture of resistance against the notion that a narrative, whether cinematic or otherwise, must begin and end.

In this regard, the decision to show Anna on a flatscreen monitor at the back of the rather brightly-lit gallery, as opposed to a large-scale projection in a darkened room as the artist has done in the past, makes sense in theory, as it places equal emphasis on the film and the implements enabling its production, and allows the two to be viewed in tandem rather than privileging the final product. While this installation, which denies the viewer the immersive experience of cinema, might have been a conscious choice, intended to draw attention to the artifice of the medium, and, as the press release notes, “the problem of achieving credible representations of violence in today’s highly saturated visual culture,” it acts to the work’s detriment: What was undoubtedly both visually engaging and conceptually sound work felt slight in this context, with the small scale of the monitor diminishing the turbulent energy of the film. That Hartung’s art still manages to captivate in spite of less-than-ideal display conditions and poorly conceived exhibition design is a testament to its strength.

Tommy Hartung, Anna

On Stellar Rays, New York

October 30-December 23, 2011