Valdez’s I Poison Myself, 2012. courtesy of Denny Gallery, New York.

In a meditation on the ‘seductiveness’ of the big toe, Georges Bataille wrote in 1929 —

human life entails, in fact, the rage of seeing oneself as a back and forth movement from refuse to ideal, and from the ideal to refuse — a rage that is easily directed against an organ as base as the foot.

Against this caliginous member of Acéphal’s tendency to luxuriate in real abjection, Amanda Valdez’s finely executed assemblages discover the joyous excesses of suggestive, corporeal forms (none of them feet), even when broken, unsettled, and then conspicuously sutured together. Her latest show at Denny Gallery, A Taste of Us, finds affinity with what Bataille describes in the work’s abiding insistence on multiple, simultaneous levels of materiality that produce an overabundance of colorful, shifting visual associations, that ultimately prompt a return to a consideration of the rudimentary, very often bodily, conditions that give rise those associations. The experience of seeing the pieces is more joyous than including a quote from Bataille might suggest. Rather than the ‘rage’ of seeing grotesque fetish objects denuded, the teeth, totems, and orifices the pieces call to mind emerge from a riot of pinks and patchworks that allow us to see the candied sweetness of excess instead of the painful cavities it causes.

With the exception of a series of small, early studies on paper, Valdez’s works construct, in the most literal sense, their frame of reference by sewing together canvas and fabrics that constitute lively shapes. These forms are then embellished with acrylic, gesso, or are painstaking embroidered to produce additional larger shapes, whose appearance changes like Moiré patterns depending on where one is standing. Swatches of iridescent orange or olive fabric are joined with untreated canvas, sewn together to either conceal or reveal the seams, and participate in a larger Gestalt with irregular painted geometries and shapes that arise from tightly crafted and variegated stitching. In the case of the embroidering, one can see the individual needle-strokes assembled in arrays that echo and coalesce with other shapes in the picture, while drawing sharp distinction with the other methods of production and calling attention to the individual hand movements required for the overall effect. This invokes not only a physical repetition inherent in the process of building a space of signification, but also its connection to the additional repetitions involved in the proliferation of a visual vocabulary manufactured through the recurrence of the fortune cookie shapes (for PG audiences) featured in many of the pictures. As such, the pictures offer an insight into scales and methods of signification, with each thread visible and lost in the ascending orders of repetition from handcraft to quotable visual abstractions.

It is in this mutual dependence and opposition between the materials out of which the pieces are ‘built’ and the overdetermined shapes they create that the show really does its heavy lifting. Everything in the pictures suggests the physical craft of its genesis, from the apparent seams and choice of fabrics to the crudely textured paint deployed as if by a hedonistic sous chef. In the larger pieces, there are no frames beyond the stretcher bars the cut-outs and shapes extend all the way to and sometimes beyond. The edges serve to emphasize the inseparability of the associations produced by the pictorial elements and the very space in which they are allowed to exist, from the modes and materials of their assembly. Signification and abstraction are bound to craft — a fact made more apparent by the inclusion of the smaller studies, where the imperfect, hasty orthogonality of pencil-drawn frames around the shapes emphasize the potential amendment or erasure of a frame altogether — something that only gains a sense of permanence when it is made indistinguishable from the materials themselves in her larger pieces.

Valdez’s Fang Legs, 2012. courtesy of Denny Gallery, New York.

What becomes delightfully evident in the show is that there is no such thing as a neutral channel for the signifier — no transparency, and no transcendental escape from the fundamentality of the material. However, in contradistinction to previous movements in modernism occupied with the problem of the materiality of the signifier, such as the decidedly political Arte Povera of the 1960s, which concentrate on the vulgarity, brutality, or excretory character of the physical and capitalistic sources of meaning, Valdez seems to enthusiastically embrace that we have imperfect bodies that can be dismembered and repaired, as do our signs and symbols. In Fang Legs for instance, one is confronted by what looks like an enormous molar painted with black gesso, with electric pink roots, glazed on the top like a pastry with black paint that creates the barest contrast with the larger black shape, and (perhaps unnecessary) embroidering between the two pink roots. There is already a frustration in the piece, at the level of naming, in seeing the tooth as a tooth, in that it has been playfully titled to direct one’s view to the possibility of seeing it as ‘fang legs,’ something which neither exists, nor do we have a proper language for, but nonetheless requires that we can call to mind an image of bodily recombination, and momentarily reconsider the immediacy of the jump to seeing it as the monster of mastication it presents itself as. Already, the notion of ‘fang legs’ duplicates the Frankensteinian logic of the works, stitching together disparate parts of the body at the level of abstraction, demonstrating the silly impurity of the polysemic universe paintings can create. The titles of many of the pieces replicate this gesture, transforming genitals and giant hearts into broad, almost literary themes like Dwells Among Us or Good to be King with a grandiosity out of step with the “craftiness” and blitheness of the pieces’ visual register.

Like many of the works in the show, Fang Legs uses traditional painterly tools for purifying the frame of interruptions to representation or abstraction precisely in order to form the representational and abstract shapes. Gesso, which would normally be used as a canvas treatment for creating a black or white uniformity on which one could then begin to paint, is the tooth, and the additional dripping black paint gloss on the top shows us how the paint and the preparations for painting are barely distinct — and moreover, it is the paint here that appears frivolous. To a similar end, in this work as with nearly every other in the show, the canvas that is sewn together with fabrics is left untreated, giving it a burlap quality that leaves all of the rough textural qualities intact in a refusal to make the pictures safe for undisturbed signification. In pieces like I Poison Myself and those that function more like slapdash quilts constructed from irregular rectangles of various fabrics, such as Temple , the crosshatched textures of the textiles are warped in the process of stretching them, forcing some level of acknowledgement that representation and abstraction are equally processes of production, and even crafts.

Valdez’s Dwells Among Us, 2011. courtesy of Denny Gallery, New York.

The conversation between pieces maximizes such a recognition in the variable expertise of handwork applied in each. Dwells Among Us displays a virtuosity of handiwork that meticulously hides and blends the seams and embroiders according to patterns that are almost machine-like (despite the fact that the image is clearly evocative of the most productive of all organic, human cavities), while Good to be King uses dark stitching that is underscored in a brilliantly superfluous three-part seam on the right side with no apparent pictorial purpose except to show stitching as stitching.

This extraneous fissure in Good to be King captures much of what the show effectively hammers away at: the fantasy of signification without seams. From the primitive and normally pragmatic crafts (like sewing) showcased for the purpose of creating overdetermined shapes that look like body parts, and which involve a clear reference to the historical modes of human production and economy, there is a sense that the meaning allowed out of excesses and beyond simple utilitarian purpose is not only already a part of all human activity, but is even a matter of physiological necessity.

At the level of the materials this is executed through unrelenting focus on the methods used in the assemblages. And at the pictorial level it takes place through bodily shapes divorced from reference to a bodily whole that allow no certainty about what they “actually” represent, which are themselves even broken or incomplete as shapes. It is at these points of breakage, in the case, for instance, of Only One, that the paint — the ultimate historical implement for representation — appears as an overflow or secretion of the craft elements. If granted my own personal excess to once more return to Bataille, we see that these excesses are perhaps at the core of human meaning production, where he wrote that the surplus of resources “which societies have constantly at their disposal at certain points, at certain times, cannot be the object of a complete appropriation…but the squandering of this surplus becomes an object of appropriation” (The Accursed Share, Vol. 1, 1991). We do not always eat because we are hungry or build for shelter. But that is what makes living, and this show, sweet.

]]>

El Lissitzky, Beat the white with the Red wedge, 1919. Via wikivisual

The paintings in the Denver Museum of Contemporary Art’s winter exhibition, Orphan Paintings: Unauthenticated Art of the Russian Avant-Garde were found, as if in a time capsule filled with Adorno’s fantasies of late capitalism, in an “unclaimed shipping container in German customs.” Subsequently, Ron Pollard, an architectural photographer in Denver, came across the inventory of unsigned paintings on, yes, eBay. Recruiting his brother Roger and a friend, Brad Gessner, the three set about purchasing the paintings in increments from the insurance administrator in Aachen, Germany who had originally bought the contents of the jettisoned freight (a more complete account of the story is available on the MCA’s website). Since then, the ad hoc group of enthusiastic collectors has hired forensic writing specialists and conservators whose expertise has given them optimism about the authenticity of their acquisitions, though their provenance remains impossible to definitively establish. And herein lies the official curatorial impetus for the show: “Can an art experience be authentic even if the status of the work of art remains questionable?”

Aleksander Rodchenko, Ornament Girls, date unknown. Via Crowds Basement

What the press release belies in its appeal to a naïve phenomenology, unencumbered by any prior art historical knowledge—an approach reproduced in the story of the collection’s acquisition by art world outsiders—is that both the conceptual apparatus of the show and our interest in its objects derives from a strong nuclear force internal to the collection, as opposed to the weak nuclear force of its story. These are not anonymous personal artifacts or wayward antique photographs in a flea market rummage bin, and thus, as the owners’ persistent attempts to legitimize the paintings suggests, they are more lost than found objects. They are paintings “in the style of” Malevich, Rodchenko, El Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, and Tatlin (among many others) which, together, suggest a formal coherence that is anything but naïve. On the contrary, the revolutionary historical moment of which they are supposed exemplars was a maelstrom of manifestos, formal dispute, ideological loud-mouthing, calculated outlandishness, pseudo-scientific speculation, and high decibel debate. This was a period when artists were very deliberate about what art was supposed to do and for whom. The modes of abstraction showcased here have very different valences depending on which work one is considering, and it is safe to assume that no matter who among the possible artists one selects, the colorful shapes are not mere objects for delectation (the press release calls it “appreciation”), or they wouldn’t be, if this was in fact a show about the Russian avant-garde. Indeed, even without assuming these works are authentic, there is an expectation that they stage a conversation (or a screaming match) about the purpose and stakes of art at the time of their alleged creation; about the artistic object, organization versus production, or the purpose of line. Yet when one enters the main room, where a painting “in the style of” Malevich’s suprematist work neighbors one “in the style of” a Rodchenko, near one “in the style of” El Lissitzky, the paintings stand in a sepulchral silence; their shabby, neglected edges diminishing rather than amplifying the auratic effect implied by the museum’s “agnostic” position towards their authenticity. And perhaps that’s the show’s virtue.

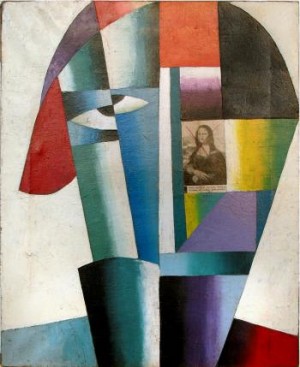

In the style of Kazimir Malevich, date unknown. Via MCA

One of the approximately twenty works in the main room is a mixed media piece that seems a lot like a Malevich. The figural silhouette looks like the head of a sculptural armature assembled from fluted shapes. The coloring conjures a techno-fetishistic vision of the new (but now antiquated) man, one built from the burnished metal bits of an older machine. The monocular eye of the figure is split and displaced as if painted on oppositely moving tectonic plates, underscoring the simultaneous contingency and sovereignty of vision. This recalls not only the more general debates about positivism and scientistic approaches to art and perception among Russian avant-gardes but also Malevich’s own theoretical writings. What is even more apparent, however, is the newspaper cutout of the Mona Lisa composing one of the shapes just right of the silhouettes’ center. Complete with its caption, and crossed out with red pencil, the not yet groan-worthy gesture of prankishness cannot fail to produce an association with Malevich’s 1914 cubist style collage, Composition with Mona Lisa, which also included a captioned picture of the Mona Lisa crossed out in red. Yet by presenting a temporally circumscribed set of works that are severed from their historical situation the show simultaneously beckons and categorically denies even these types of superficial comparisons. The result is an impossible latticework of counter-factual suppositions about the formal operations on display and a question about what, besides “experience,” the viewers are warranted to do when looking at such a collection.

Kazimir Malevich, Composition with Mona Lisa, 1914. Via aiwaz.net

If you believe, along with someone like Peter Bürger, in the historicity of aesthetic categories, particularly with respect to avant-garde movements, then didactics do little to illuminate the original conditions of these paintings’ production or, for that matter, that of the paintings they look like. The premises of the exhibit do not exceed a novel collision between the possibility of the collection’s authenticity and the curious circumstances of its discovery (circumstances that make its authentication unlikely). But while the “experience” of the works, which are mostly abstract, frequently insists on a theoretical scaffolding that the museum refuses to provide — and which the paintings themselves can only hint at — this moment of frustration serves as a kind of instructive aporia. When, in the early 1920s, artists like Rodchenko pursued a machine aesthetic, employing industrial materials in order to “build” artworks with a meaningful social-utopian function, the artwork was intentionally forced into a direct confrontation with the fundamental, material means for its creation—industrial materials, technologies, and techniques, representing the speed, efficiency, and automation of new forms of production. Deploying these productive forces in the work was thought not only crucial to art’s participation-in and representation-of the ideological aspirations of the artists, but also instrumental in the transformation of the sensorium. Modes of perception and consciousness were the products rather than the sources of the material conditions they observed, and therefore, art that engaged those conditions could reformulate the terms of its own reception. In the case of the Orphan Paintings, however, the artworks are submitted to a sensorial regime instructed or even governed by economic conditions posterior to the paintings’ own utopian visions. Instead of making something of the viewer, the viewer is asked to make something of the artworks; a herculean task that ultimately seems to prove the dependence of “experience” on its material-historical situation. It is fitting that these paintings should arrive at their future in an abandoned metal freight to be sold on eBay—a future in which economic speed and efficiency have themselves become abstract and yet can no longer be represented abstractly.

Kazimir Malevich, Suprematist Composition, 1916. Via Sotheby's

As a kind of forgotten remainder of a material dialectic, these works can be viewed as a pure surplus without a surplus value (think of Malevich’s 1916 Suprematist Composition fetching $60 million at Sotheby’s in 2008). They are no longer really art according to the market (as they were turned down by auction houses), nor do they participate in any existing social or political discourse. In the moment when the craving for material verification becomes most aggravated—the point at which we most desire some physical documentation linking these paintings to their ostensible origin—these paintings become apt tools for instructing us on the contemporary, immaterial conditions required for the production of artwork. The viewer’s inability to securely situate the apocryphal works historically, coupled with the paintings’ apparent preoccupation (as potential works of the avant-garde) with the historical and material conditions of their reception, prompts a meditation on the current conjecture preventing us from making much of these images. In this way, the show serves as a grim, if useful, epilogue to avant-garde utopianism. While, at the same time, precisely by dismantling bourgeois notions of authorship, the anonymous circumstances for the reception of these paintings successfully realizes certain aspirations of the avant-garde, albeit through a glitch in a particularly dystopian form of advanced capitalism.

]]>