Via absolutad.com.

Palladio

By Jonathan Dee

(Corsair, 448 pp.)

By Francesca Mari

The writing guru William Zinsser basically said you should never, ever use the exclamation point. “It has a gushy aura,” he writes in On Writing Well, “the breathless excitement of a debutante commenting on an event that was only exciting to her.” But by 2003, they were springing out of my emails. Call them sincerity points, for that’s what I realized I intended (and still intend!) by them—a sort of allegiance to earnestness. Throughout the 90s irony had become so pervasive that it was no longer possible to determine whether someone was being sincere or sarcastic, and so I embraced even the gushiest of antidotes—along, it seems, with everyone else. Exclamations now punch up even office emails, and not just one or two, but often over seven in a row.

Irony isn’t inherently degraded. It has, as Lewis Hyde pointed out, emergency use. But “[c]arried over time, it is the voice of the trapped who have come to enjoy their cage.” David Foster Wallace sensed this amassing cumulus of irony in American culture like an arthritic senses the rain. What turned it so toxic he argued in “E Unibus Pluram” from 1990, was television. The prevalence of TV, consumed at an average of six hours a day, meant that when Americans weren’t working, most of what they were doing was watching. And so America began “exchanging an old idea of itself as a nation of do-ers and be-ers for a new version of the U.S.A. as an atomized mass of self-conscious watchers and appearers.” To assuage citizens that they were above the vulgarity of whatever was served up on the screen, TV spiced its content with irony—a new, all-engrossing irony in which sound teamed together with visuals to completely submerge a viewer in a feeling of superiority. The constant submersion, in turn, rendered written irony all but impotent. When fiction pitches its one-dimensional irony at our media-saturated culture, the result, Wallace argues, is mere meaninglessness—one writer saying things he or she doesn’t mean to point out that the TV says and shows things it doesn’t mean. “The reason why our pervasive cultural irony is at once so powerful and so unsatisfying is that an ironist is impossible to pin down.” Wallace’s exceedingly conscientious fiction prevails over irony with an obsessive and amphetaminic curiosity. He details his prose with as many inquiries, facts, and footnotes as there are strokes in a mandala thangka. Relentless curiosity is Wallace’s cure.

Nearly ten years later, the American novelist Jonathan Dee made a similar critical cry in his Harper’s essay on the Clio awards for advertising: The subversive deadpan that powered great art by Roy Lichenstein and Robert Coover and Talking Heads has withered into a cultural reflex, a complicity; the smirk of ironic disengagement exchanged between artists and audience now refers to nothing but itself, like two mirrors held face to face.

Over the past twenty years, Dee has published five novels—The Lover of History came out in the U.S. in 1990, followed by The Liberty Campaign (1993), St. Famous (1996), Palladio (2002 and this year in the U.K.), and The Privileges (2010). Set in America, they are preoccupied with stereotypical American themes, most prominently success and selling out in art and advertising. Dee embraces as his subject and style the do-ers and be-ers of yesteryear, the active and assured men whose decline Wallace noted. But rather than analyzing with the intensity of Wallace—which muscles make a smile a smirk? which thoughts tighten what muscles?—Dee’s fiction takes a behavioral approach; his books make their point through their plot, through the actions, rather than the meditations, of his characters. And taking action is just what generates success in Dee’s America, too. Whether trading stocks, founding a firm or playing professional baseball, success—for better or worse—is “based on a vast architecture of belief,” as Dee writes in The Liberty Campaign, “in the idea that the spirit is rewarded and ambivalence punished”. The only way to get what you want is to go for it, and the same applies to art.

Acting on conviction is the key to success, and what’s surprising given Dee’s critical righteousness is that he portrays the success of wrongheaded conviction as often, if not more so, than that of the right-headed kind. When in The Privileges a hedge-funder’s hot wife falls into a depression during her swathes of spare time, her husband hastens to make heaps of money through insider trading so that she might be occupied by the spending of it. Charity board meetings, real estate acquisitions and redecorations ensue. The novel couldn’t but benefit from the bailouts still defining the news at its publication. But when given the opportunity to edit the manuscript in 2009, Dee merely elided details that placed the novel in the now. Instead he sought to answer timeless questions: What can love wreck if it’s between bad people? What about simply selfish ones?

So it is not with naïveté that Dee depicts action as an antidote to irony. Nevertheless Dee maintains the necessity of conviction and corollary action. When the pretentious writer-protagonist of his third novel, St. Famous, stands to make a ton of money by publishing an account of his abduction during Harlem race riots, he has an ethical crisis, hinging on his lack of initiative: how can he make art of his experience when he was the abductee rather than the abductor, the object of the event rather than its orchestrator? His black assailant agrees, seizing the manuscript by gunpoint. “This story is about me!” he insists. “Without me, there’d be no book, there’d be no money, and you’d still be nobody. You didn’t act—you did nothing!” You didn’t act: despite its ridiculousness as dialogue, it’s a resonant accusation, and Dee’s credo has everything to do with it.

In order for art to be authentic, Dee believes it must create original meanings and ordain new events. “I still think of art as making something,” the protagonist of Dee’s fourth novel, Palladio, says after viewing ironic works reminiscent of Damien Hirst’s shark and Janine Antoni’s bitten chocolate sculptures. “Not causing it to be made.” While Wallace’s resistance to irony is immediate and overpowering, Dee’s is subtler because he forbids neuroses from entering into the narrative. Although his characters, writers and artists among them, struggle intellectually, their Big Thoughts arise for the sake of making decisions. Dee wards off irony with action, rather than inquiry. But not only is Dee a supreme and suspenseful plotter, his characters are plotters and inventors, too.

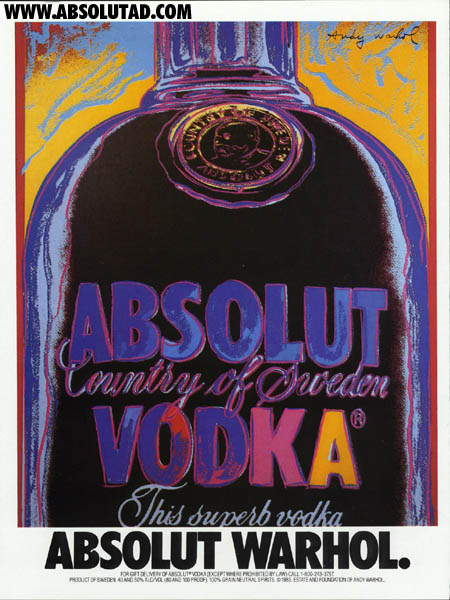

John Wheelwright, one of the protagonists of Palladio, is a creatively constipated illustrator who’s dissatisfied with his job at the epicenter of irony—at a Madison Avenue ad agency replete with Backstreet Boys Frisbees and Farah Fawcett posters. When Mal Osbourne, the agency’s reclusive partner and idiosyncratic art collector, invites him and a number of other prominent ad people to be a part of an earnest new advertising agency named Palladio, he gives up his Brooklyn life and lawyer girlfriend to relocate to their office-cum-plantation in Charlottesville, Virginia. Meantime, as Palladio develops (Dee braids multiple narratives in all of his novels), so, amid the dairy farms of upstate New York, does a little girl named Molly Howe. Intense and aloof, she’s ostracized by the town after an affair with a married man and moves to Berkeley, where she falls in love with John Wheelwright, then an art history major. They share an apartment until one day she flies home and disappears. When, ten years later, she unwittingly reappears at John’s office, John and Molly’s narratives are soldered together in the present, and Mal falls for Molly at first sight.

If Palladio’s concerns seem inconsequential, it’s worth remembering that, although the novel was published in the US a year after 9/11, it was written before, when the threat of terror hadn’t yet roused post-traumatic earnestness in the public discourse. And so the book describes a pre-9/11 America, a pre-recession America, a country with no dire enemies or economic difficulties to define its purpose or to call it to action, a country that needed to defend meaning from no one but itself. Consider the Volkswagen ad Dee describes in Part I, which ends with, “Perfect for your life. Or your complete lack thereof.” That’s the sort of glib irony we would, in the post-nineties era, fend off with our sincerity points, and it’s this particular slogan that stirs Mal Osbourne to action. In fact, Mal’s letter of recruitment echoes Dee’s Harper’s piece almost verbatim:

Our culture propagates no values, outside of the peculiar sort of self-negation implied in the wry smile of irony…. That wry smile mocks self-knowledge, mocks the idea of right and wrong, mocks the notion that art is worth making at all. I want to wipe that smile off the face of our age.

And what Mal intends to wipe it with is avant-garde art. In the venture Mal proposes, companies can contract a piece from one of the agency’s esteemed artists, but they can’t dictate which one, or control the content, or even apply their logo. Mal wants to disseminate art so awe-inspiring that the mystique of its origins will do all the selling. He hopes commercial patronage will protect the integrity of art: By providing financial security and the means to reach a vast audience, subsidy by commercial clients can dispel art’s anxiety over expense and relevance—two concerns that drive it to a defensive irony. Indeed the root of the agency’s name refers to this: palladium in ancient Greece referred to an image of Athena (or Pallas) believed to safeguard Troy from attack. Note that Dee names his novel the same.

But even when writing about a hedge-funder and his wife, Dee isn’t a writer fraught with recriminations. Let his characters hang themselves over and over; you won’t find Dee in the galleries saying they deserved it. Unlike Franzen, a writer just as contemporary, male and readable, Dee contains his liberal excoriations. He isn’t subsumed by freewheeling suspicion like Don DeLillo. Nor does he resort to the free and direct indictment of Richard Yates, who ruthlessly impeaches his characters by chronicling their every delusion. Dee is, by his own admission, a congregant of Milan Kundera’s Objectivity. The novel, Kundera wrote in Testaments Betrayed, is “a realm where moral judgment is suspended. Suspending moral judgment is … its morality.”

Against all odds, Palladio thrives, and gives purpose to an array of detractors. A group of professors calling themselves CultureTrust (another name that stands for a “safeguard”) ironize Palladio’s art. Onto Palladio’s “End is Near” billboards, for instance, CultureTrust spray paints dollar signs and adds a “TR”: “The TREnd is Near.” When a gallery sues two of the professors for another act of defacement, Mal sends John to handle the situation—John who, failing to produce one good bit of art, has been “promoted” to Mal’s fixer and second-hand man, a job suited to his unimpeachable earnestness. John sits in the professors’ cabin, weathering their mockery, then offers to hire them for a starting salary of $1 million. “It’s a sincerity check,” John tells them. “Because I think that your idea of yourselves is predicated on failure. You enjoy making these destructive gestures precisely because no one’s listening, because you know no one cares what you think. Well, here’s a chance for you to take the ideas you hold so dear and make the whole world listen to them.” It’s an interesting assertion, suggesting as it does that audience is the purpose and validation of art. When the professors counter the starting offer of one million dollars with a request for two million, John says he’ll see what can be done. And he maintains this maddening poise when they ask for five million, then ten.

But nothing is more intriguing than the pursuit of sincerity—or insincerity—through sex, and this, perhaps, is one of the reasons Palladio opens with the “intense” and long-lashed Molly Howe. Molly is a non-do-er, almost a non-be-er. Obsessed with music as a teen, she has no aspirations to make any: to her, “Listening well was the act.” From childhood on into her twenties, she feels little, says less, and is adoptable as an accomplice to any act—curious to see what men expose when they expose. In fact, in Dee’s depictions, Molly sidles dangerously close to male fantasy, bedding the kid with burn scars; the chauvinist cop; the husband for whom she babysits. Irony threatens the quiet town of Ulster, but if it had total reign, everything would just sordidly continue as before, a wholesome town concealing squalid betrayal. Instead Molly seeks refuge with her brother because Dee depicts a world in which complicity has its consequences.

Molly’s inscrutability solicits powerful impulses, good and bad, in others. She is, as John Dewey might say, a love object that induces sympathy, which in turn spurs action. Falling for Molly’s same “involving” that engaged John’s imagination back in college, Mal tells John, “there’s something about it that’s intolerable really… it makes you want to fill it up”. Ever complicit, Molly accepts Mal’s advances, despite being his almost archetypal opposite.

For all Mal Osbourne believes and contributes to the world, the demure Molly Howe subtracts with her nothingness, her nihilism. Yet Molly doesn’t meet Mal’s earnestness with irony. Irony succeeds only if the speaker and the listener are both in on the subtext. To understand irony is to disbelieve what’s being said, to understand that what’s meant is just the opposite. So by excluding the ignorant, irony extends a false sense of intimacy. It’s not so different, actually, than the false intimacy between Molly and the despicable people she sleeps with. Just as irony is an anti-statement, Molly’s promiscuity is an anti-action. With the possible exception of her early dealings with John, nothing about the deed is meant: not baby-making, not love, not even lust or like. And so Molly serves as a warning; she’s not an embodiment of irony, but the effect of it, the seductive nothingness after its course of corrosion.

But Dee’s prose dabbles in no such nihilism. Palladio opens like a 19th century novel, prophetic and elegiac, upon Molly’s home town. “A town called Ulster,” Dee writes as his first sentence, “prospered briefly in the 1960s and 70s” , and that simple but beautiful phrase—prospered briefly—might serve as an epigraph for the entire novel, blueprinting, as it does, the evanescence of the relationships, towns and companies depicted within. Yet in spite of the brevity, every word is sincere. “John,” Dee writes, when John and Molly are falling in love, “never pushed for more; he politely accepted every answer as complete, even when she was obviously holding something back. Nor was he the kind of boy”—and here Dee elevates description into perception—“who listened to your speech hoping to hear something which would remind him of a tangentially related experience of his own, which he would then explain in full, as if this were evidence of empathy of some sort.” In one swift sentence, Dee hones in on John’s particular personality by enlarging the narrative to articulate a misguided tendency that plagues swathes of people. Going from description to perception, that easy striding from the particular to the general, is life-affirming; there’s a reassurance, a comfort, to the placement of an individual within a tendency.

Only once does Dee’s stylistic “doing” perhaps go too far when, in the aftermath of Palladio’s implosion, he inserts the avant-garde into his own work. The third and final section is a slideshow of epilogues, briefly depicting where each character settles after leaving Palladio, and each portrait is punctuated by an authorial “*MESSAGE*,” a Dadaist prose poem printed in a mishmash of different fonts. “THESE ARE REAL PEOPLE,” begins one. Another reads, “Art or Advertising? Either Way, Seoul is Mesmerized.” Lifting the pedagogical tones of religion, science, art and advertising, these postmodern bits of nouny bravado assert themselves like speed bumps into the otherwise smooth narrative. Failing to contribute new meaning, if these be art than it’s of the ironic sort the book rails against.

These metafiction montages fail in a larger sense because Dee’s strength isn’t his ideas—it’s the optimism of his impeccable, old-school plotting. “Plot is a construct,” says the pretentious writer-protagonist from St Famous who views it as defining fiction. “Plot is a superimposition.” That is to say, it’s a deliberate act. The invention of events that seem natural such that they are easy to believe, and being believed, such that they convey meaning, is a sustained act of hope. The will to spend hours, years, sitting at a desk, staring at the ridges of the plaster on the wall, all for the sake of fitting and reinforcing an imaginary scaffolding, requires confidence in humanity—or at least in the humanity of one or two readers. Particularly given Dee’s allegiance to moral objectivity, it requires the conviction that readers will derive a sound moral from the narrative. Depicting characters in pursuit of purpose—creating new ventures, seeking authentic relationships—Dee contributes plot to overpass the inky well of irony. For the most part these pursuits briefly prosper, but ultimately go the way of Ulster. Dee’s stories are fated. But what’s remarkable about Jonathan Dee is that the world he portrays isn’t.

]]>