image courtesy of Farrar, Strause and Giroux.

Poems: 1962-2012

Louise Glück

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012

When I was a little bit younger, I thought of Louise Glück as the embodiment of one idea of a poet. She was incisive and dark, she knew how to be commanding, scornful, or tender. She kept her poise in the face of known or unknown terrors —

Look at the night sky:

I have two selves, two kinds of power.

I am here with you, at the window,

watching you react. Yesterday

the moon rose over moist earth in the lower garden.

Now the earth glitters like the moon,

like dead matter crusted with light.You can close your eyes now.

I have heard your cries, and cries before yours,

and the demand behind them.

I have shown you what you want:

not belief, but capitulation

to authority, which depends on violence.

I knew this was not the only way a poet could speak, not the only way a speaker could behave, but it seemed like the essence of a certain kind of ‘poeticism.’ Weren’t these the sort of things a poet should talk about? Shouldn’t a poet address his or her own loves and desperations as nakedly as possible? No matter what dimensions the poem took, she kept faith in the potency of a single lyric speaker.

The author of eleven volumes of poetry spanning more than forty years, both altering the commonplaces of poetry and her work to match time’s arrow, Louise Glück is far more complicated than my imaginary picture. But there is something persistent in the idea of her work and the way it stands apart. It is related to what readers of poetry often call a poet’s ‘voice.’

Part of the pleasure of reading a book of collected poetry, apart from the misplaced passion of the completist, is to watch the development of a poet over time. When a body of work is amassed, it becomes like geological strata. Each layer marks change and development, either gradually or by a rapid turning away from old materials. It is not the only way to examine a body of work, but it is always an attractive one — the narrative begins to write itself.

I’m inclined to read Glück this way for a few reasons. For one, Glück repeatedly explores her personal life in her poems: husbands, children, lovers, and family members are constant subjects of her work. Less directly, Glück is a poet popularly known for creating book-length sequences of poems. Several are organized by a classical myth onto which Glück maps her personal life and poetic voice (Odysseus, Orpheus and Eurydice, Persephone). Others are matched together in more subtle ways. To me, this suggests a constant, and self-conscious, search for unity from within in Glück’s work. It doesn’t seem like a reach to envision an attempt to curate a life through successive volumes — at least there exists an invitation to consider the poet herself (as personality) as the unifying idea behind the body of work.

I think every poet imagines his or her work to be cohere over time in some way, if only by virtue of the fact that the same mind arranges words on a page in both 1968 and 2009. When I look at the disparate books and the multitude of individual poems that cluster in a collected volume, there’s a natural tendency to generalize, to look for the threads that bind the work together and create a consistent idea of the author. In particular, it is the unique containment of Glück’s voice that interests me, the control that comes from her careful circumscription of language and concepts.

Here’s a simplified way of thinking about poetic voice: it is the imprint of a writer’s combined choices of words, phrases, and forms. It is grasped more easily as an entire impression (constructed from our reading) rather than as a specific understanding of particulars. As a reader, I build in my head a model of what kind of person a writer might be, and furthermore what kind of writer that writer might be. This abstracted sense of a writer often leads to the idea of voice, on one hand corresponding to what he or she actually wrote, but also allowing us to imagine what he or she might write in a different context. A sense of voice allows us to imagine what might have been in an author’s burned notebook.

This abstracted idea of voice is different from, but does not necessarily conflict with, the practice of reading a collected body of work like Glück’s. The abstraction runs alongside the particulars — it is a heuristic, a guide to impressions as we accrue more information. As we read, certain details may not match our larger picture. However, an increasingly complex view of a writer’s style does not make the generalization irrelevant. We must always be careful not to confuse the map with the territory.

Glück’s first book, Firstborn, was published in 1968. As one might expect in a first book, the distinctive parts of Glück’s voice are less obvious. This makes the poems instructive by comparison: the later hallmarks of voice are nascent but have not yet been developed. It is also fascinating to see the poet still dabbling with traditional forms of meter and rhyme before largely abandoning them. For example, take the poem Labor Day:

Requiring something lovely on his arm

Took me to Stamford, Connecticut, a quasi-farm,

His family’s; later picking up the mammoth

Girlfriend of Charlie, meanwhile trying to pawn me off

On some third guy also up for the weekend.

But Saturday we still were paired; spent

It sprawled across the sprawling acreage

Until the grass grew limp

With damp. Like me. Johnston-baby, I can still see

The pelted clover, burrs’ prickly fur and gorged

Pastures spewing infinite tiny bells. You pimp.

The hesitant insertion of a few rhymes seems like a reflex indicative of the poem’s larger project: an attempt to completely embody a particular moment. Miniatures like these work to create an image or discrete event, and the clear presentation of this morsel is a successful when it lets us know something new about our reality. It is only ambiguous insofar as the moment in life is an ambiguous one. To capture such a moment requires control — it is important to get the image exactly right as it occurs.

In the need for clarity, the roots of Glück’s distinctive voice can be easily seen, from the tone of scorn to the turn to nature at the poem’s end. There is something both solemn and invasive about Pastures spewing infinite tiny bells. The accusation of You pimp bluntly sums up the conflict of gender, the dual attraction and repulsion that is common in the author’s later books. The final words fall heavily, perhaps unartfully, but it gives an indication of the assertiveness of one of the most distinctive aspects of Glück’s work — of the voice.

In later books, the concreteness of poems like this becomes increasingly rare. Consider the opening lines of Mock Orange the first poem in Glück’s fourth book, The Triumph of Achilles:

It is not the moon, I tell you.

It is these flowers

lighting the yard.I hate them.

I hate them as I hate sex,

the man’s mouth

sealing my mouth, the man’s

paralyzing body —

You pimp can be accessed anyway, without having to create an image that the reader can visualize. The generality of voice and its characteristic gestures become more important than the idea of recreating a particular moment. The generalization often begins by the omission of particulars, creating a world only inhabited by broad nouns: moon, flowers, light, hatred, man, mouth, body. The stripping down of the voice to its essentials becomes an unusual self-consciousness: a voice primarily concerned with voice.

Another related tendency of the first few books is the attempt to embody other speakers in particular poems, often from extremely different perspectives or historical backgrounds. In reality these are less authentic inhabitations of other lives (as a certain kind of short-story writer might attempt) than new garments for the same persistent voice. In a certain sense, this adoption of nominally “other” voices attempts to strengthen the single Glück voice, asserting that its music is trans-historical. A representative example of this is Jeanne D’Arc, from The House On Marshland, Glück’s second book:

It was in the fields. The trees grew still,

a light passed through the leaves speaking

of Christ’s great grace: I heard.

My body hardened into armor.Since the guards

gave me over to darkness I have prayed to God

and now the voices answer I must be

transformed to fire, for God’s purpose,

and have bid me kneel

to bless my King, and thank

the enemy to whom I owe my life.

Like Jeanne D’Arc, it is a compact poem requiring little deciphering of its basic elements. It faithfully represents the story of Joan of Arc as we know it, but is also an obvious cypher for the features of Glück’s poetic language: self-sacrifice, the possibility of an ecstatic message in nature. It may seem reductive to paraphrase in this way, but really it is the lack of ambiguity that makes the poem interesting. Jeanne D’Arc, is an appropriate skeleton for the uncompromising voice, and through history she is more the idea of a person than a physical entity. Accordingly, in her later career Glück commonly favors myth, parable, and fable as the frameworks for poems, looking for narratives that can support an exact, simplified emotional language. The idea of form here and elsewhere is similarly spare, using line breaks more as a convenient pause (a suggestion of breath) than as a formal pattern. The implication of this choice is almost always a kind of urgency, as though the line were trying to break through into unmediated utterance.

This is not to say that this directness is an absolute good, but simply that it is one of the defining elements of Glück’s voice — though her tone softens in later books, it would be hard to imagine her voice modulated into, say, found language or even prose poetry. In her work the limits of lyric are defined, the adherence is essentially religious. Though voice is often recognized in gestalt, we can point to many of the choices made that create Glück’s in particular. The parameters of subject are narrowed down quickly: nature, family, season, myth, love, death. The speech act itself is usually highly charged, manifesting as accusation, confession, or a sharp statement of preference.

This is an old-fashioned universe that has been built up with care. To many modern readers of poetry, those at home with the now-pervasive skepticism of contemporary art, it may seem obsolete, like an obstinate landscape painter who continues toiling, outflanked by more daring peers. A sophisticated reader naturally questions the validity of this voice as an intact, seamless phenomenon exactly because it comes on so strong. The reader is rarely, if ever, provided with the relieving wink that demonstrates that the speech was a performance. Added to this, Glück does little to display her intellectual credentials, consistently favoring the language of emotion. This is just as one might have questioned the claim of an Abstract Expressionist painter to his own personal visual or aesthetic hallmark in the face of something like Pop Art. The interrogation is apt, but is maybe also missing something.

A common expression of this skeptical tendency in poetry has been to raise questions of the incommensurability of language. By putting the power of poetry on trial, writers hope to be vindicated when the world answers in the affirmative. It is interesting that Glück very rarely makes such a gesture. She lies on the opposite end of the spectrum: here the poet declares her absolute power over words. In the final words of Parodos, the first poem of Ararat, Glück makes this explicit:

I was born to a vocation:

to bear witness

to the great mysteries.

Now that I’ve seen both

birth and death, I know

to the dark nature these

are proofs, not

mysteries–

There is some irony here, but perhaps only a touch. Glück’s self-assigned project is to turn mysteries into proofs with her power of vision: she looks to find clarity in poems again, as opposed to the modernist heritage of opacity that still looms over literary discourse. Reading the above words, it becomes apparent how used to reflexive gestures I am, and that their absence is both interesting and risky. I naturally ask myself the question of whether the poem that has come before these final lines can sustain such a deeply serious punctuation, or if there is some clever counterpoint I’m missing. What skeptic of art would even attempt to write such lines? To me, this is the appeal of Glück’s circumscribed voice: instead of reaching outward, she gains power by dominating poetry’s most familiar territories.

The title Parodos evokes ancient Greek theater, so there is some reference to the artificiality of this kind of speech, but only a passing one. The Greeks for Glück have much more resonance as an icon of deep seriousness, where tragedy is the only truthful outcome. The limitations of this approach can be seen in Meadowlands, a collection that joins in the tradition (now nearly as ancient as the source itself) of re-creating Homer’s The Odyssey in a modern context. Odysseus’ journey becomes a map of correspondence for poems that reach into Glück’s personal life, particularly her marriage and the raising of her son. In this edition the distant husband becomes Odysseus, the wary son becomes Telemachus, and the long-suffering wife becomes Penelope. It is perhaps because of the facility of the comparison that the seams show a bit too much. I’m not convinced that the value of The Odyssey lies completely in its similarity to us. Meadowlands is also, not coincidentally, the first book that seriously begins the treatment of the subject of aging. This in itself is not a disquieting additive to a lyric voice, but with Glück it begins to weigh on the poems, blunting their ability to be arresting.

In Ararat, along with The Wild Iris, two of Glück’s most characteristic collections, the power of her voice’s distillation is most apparent. In some ways, we can think of voice is simply an over elaborate way of saying style. In a strict sense this may even be true. Voice, however, has an extra connotation: voice always presupposes a unified consciousness. The lyric poet relies more than any other artist on this conception of a unique, individual voice, a personality behind the screen that breathes life into the artifact. Maybe it is more complete to say that voice is the play between our abstraction and the recognition of a concrete individual who creates his or her own poems.

It is important to make this clarification, as Ararat is the most direct example of what could be called the confessional tendency in Glück’s work, a critical buzzword of poetry now long bypassed. Glück’s personal revelations of marriage and raising a family provide a link to the classic generation of postwar American poets like Lowell, Sexton, and Berryman. It does not seem like a stretch to think that these authors are among the strongest contributors to contemporary poetry’s conventional idea of having a voice. If one goal of poetry is to surprise a reader, one way to do this is to disclose a secret. These poets realized that one way to do this was to literally render up the secrets of their lives. However, any trope is subject to fatigue by repetition. Glück’s poems here are stark and sharp, but they never seem to give too much away about her personal life. Confession is more of a frame for that same raw voice than an attempt to reveal the actual secrets of the author’s life.

In The Wild Iris, Glück’s voice reaches its most intense and most abstract heights. Several of the poems are named either Vespers or Matins, bolstering the intuition that this language is fundamentally a religious language, a language that might have the power to transform through utterance:

As I perceive

I am dying now and know

I will not speak again, will not

survive the earth, be summoned

out of it again, not

a flower yet, a spine only, raw dirt

catching my ribs, I call you,

father and master: all around,

my companions are falling, thinking

you do not see. How

can they know you see

unless you save us?

In the summer twilight, are you

close enough to hear

your child’s terror? Or

are you not my father,

you who raised me?

The collection is constructed around the idea of a garden and its inhabitants. The flowers are able to take up Glück’s voice and thereby become conscious of their own cultivation and repeated destruction. It’s an appropriate framework for mapping the author’s normal concerns. The relationship between lily and gardener easily becomes the relationship between god and man, father and child, or master and slave. Lines like How / can they know you see / unless you save us? are in some ways profound, but are also somewhat contentless. Glück can ask the same question in all circumstances described above. It is the sound of a voice in motion, and the reader concentrates on the sound of the plea rather than the specific question asked.

Between The Wild Iris and Meadowlands it’s hard not to detect a fundamental change. Glück’s early career seems to lead up to The Wild Iris, and that book’s cohesion and stringency is not to be underestimated. Meadowlands, on the other hand, feels like the beginning of a descent. In the later books, I sense the reins being loosened. After the author’s voice has been constricted to the narrowest possible specifications, the only answer that lets a poet keep writing is to expand the range of possibilities. There are many fine poems from Glück’s later career, but they sometimes feel less sharp, more forgiving. Attempts at humor and lightness seem jarring. This is perhaps unfair, but it was the fine-tuning and precision that made the early poems so powerful. Later on, there is more of a complex person behind the poems, but the language itself — simple, dark, emotive — is still equipped to serve the sharpness of the old disembodied voice.

There is both power and weakness in Glück’s poetic language. It is as if a partition is being constructed in order to hold in what is most valuable in poetry and to keep out whatever might threaten these essentials. But circumscription has its costs too: there is a distinct sense of fatigue in reading so many examples of one finely tuned model for poems. The risk of cliché is real when the same archetypical gestures return to poems again and again.

But Louise Glück is not intended to be a model for all other poets. It is difficult to imagine a poet today choosing such radical self-limitation. Perhaps the strain of the Information Age is too great, the perceived need to constantly respond to diffuse surroundings is too demanding. In that case, Glück’s voice is a reminder of the usefulness of a kind of aesthetic discipline, a ruthless desire to seek out the core of the poem. At least in my case, the love song and the image of light streaming through the trees brought me into the world of poetry. We have to be careful in thinking about these most well worn parts of poetic language, the parts that rest on the precipice of cliché. If the changing of the light in the seasons can only become chatter, we must be careful to see that we have not lost the ability to speak of such things at all.

]]>

My Struggle: Book One

Karl Ove Knausgaard

translated by Don Bartlett

Archipelago, 2012

In order to become an author, how should a life be? Lurking somewhere in brain or heart of the ambitious writer who seeks to harvest his or her own story, this question seems both obvious and somewhat disreputable. One thinks of, among many examples, the anxiety of Stephen Daedalus, who asks himself by what right can he be transformed into an artist, later finding an obscure answer in his own sense of beauty. It seems that if you have to ask, you’ll never know. Yet the question is overcome time and again, and the künstlerroman is alive and well.

One traditional solution to this question of authority has been the methods of the roman à clef. The proposition of the roman à clef is to mine the material that comprises the author’s life, combing the years to discover the memories and experiences that are most vivid for the author (and those which can be most vividly expressed). This material is reincorporated into the framework of the novel’s fiction, and the author thereby gains distance and the freedom to reshape events as necessary. In this mode, literary form dominates life.

In recent history, the straight memoir or autobiography has held a subsidiary position to the novel. One crucial difference rests in a traditional assumption about the ocean of detail that fills out a life. Life, as it is lived, is full of detail that has no obvious literary value: what we eat on a given day, where we go shopping, the buildings on a walk we take between two places, people we see on the street. The roman à clef is a tool that digests the details that would otherwise fall into a memoir, rearranges them as necessary, weaves them into fabric of literary tropes, and raises them to the status of a universal. The distinction of changing a name, a person’s characteristic tic, or what was served at a meal seems small, but its strength is belied by the persistence of the convention.

However, it’s a convention that raises an equally persistent counter: if the desire of an author is to tell or explain something about the world as it is, how can this manipulated reality be more real than the events as they occurred? Presumably this is part of the appeal of memoirs and biographies: to gain unmediated access to real events. To know about things as they really were and are. Recently it has been suggested that the craving for this type of information has begun to exceed the desire for symmetry and order of the old literary forms.

Karl Ove Knausgaard is a Norwegian author, forty-three years old, and the author of two previous novels. My Struggle is the first translated volume in an enormous, six-volume project of autobiography, subtitled as a novel in the original edition (though this appellation, interestingly, is omitted from the US edition).

This first volume is divided into two sections. The first is largely a series of childhood recollections unassumingly told, spanning the mundane, the humorous, and the poignant. The second part deals with the death of Knausgaard’s father, a solitary and sometimes cruel figure who is constantly present in the young Karl Ove’s thoughts throughout the book. Knausgaard’s father abandons his family and slips into a spiral of alcoholism, leaving the adult Karl Ove and his brother to pick up the pieces when he dies in squalor. These are the two main keys in which the book is played, but the structure is loose, and along the way are digressions, miniature essays, and detours back to the “present tense” of writing the book itself, where Knausgaard reflects on subjects as diverse as contemporary art and the displeasures of raising children.

The books have created a scandal (as well as record-breaking sales) in Norway for the frank disclosure of the secrets, deeply private and occasionally sordid, of Knausgaard’s family and marriages. Knausgaard has himself called the writing of the books a “Faustian bargain.” The outrage comes from a specific cultural context (Americans, for instance, are no strangers to the tell-all memoir), but Knausgaard’s ambitions are clearly international. As the stock of nonfiction continues to rise and the memoir is not only critically accepted, but is regarded as having equal footing with the novel, My Struggle is a particularly timely work. However, the role that My Struggle fills in this shift is not exactly clear.

The most obvious literary forefather is Proust, who Knausgaard acknowledges early on as a generative source: “I not only read Marcel Proust’s novel À la recherché du temps perdu but virtually imbibed it.” However, Knausgaard does not aspire to the perfect architecture of Proust, or his ability to create a disquisition on any object that falls into his field of vision. Nor is he a descendant of the postmodern impulse to interrogate the line between truth and fiction, or to question the sources of truth or the author’s authority. Knausgaard is an aesthete, with an affinity for Old Master painting and some views that could be called conservative. It may be more helpful to think about My Struggle as a contestation of conventions dividing fiction and memoir, but with roots in an older tradition that unironically holds up the power and self-sufficiency of works of art. Knausgaard seeks to destroy, but also to reinvigorate.

For instance, the book opens with an early episode in the interpretation of life’s raw material. The young Karl Ove, aged eight, is watching a TV news report about a sunken fishing boat and suddenly sees the outline of a face appear in the contours of the sea. He runs to tell his father, who remains impassive and uninterested, hammering away at a boulder in the garden. The moment seems almost overripe with metaphorical significance, but Knausgaard deliberately takes care not to exploit the moment in a conventionally “novelistic” way. Instead, he moves to an almost essayistic register, explicating this formative moment in a surprisingly forward way:

Meaning requires content, content requires time, time requires resistance. Knowledge is distance, knowledge is stasis and the enemy of meaning +

From the start, the reader is forced to consider the proposed schema. Knausgaard, both as character and as narrator of his own life is obsessed with the idea of “meaningfulness.” To many readers, taking “meaning” wholesale as a concept may seem rather dubious. Knausgaard’s mission is partly to rescue the term, and he tends to think of meaningfulness as the feeling of meaning. If the impression of meaningfulness is paramount, it seems natural that Knausgaard’s pole stars are childhood and family tragedy, particularly the death of a parent.

By contrast, “knowledge” is considered to be a less valuable way of looking at the world, a way of abrogating experience and replacing it with information. In childhood, everything is meaningful exactly because so little is known, and everything is invested with potential of what things might be. An adult may still have meaningful experience, but it is always mediated by the voice of reason in his or her head. For instance, when Karl Ove’s father dies, the adult narration looks for an explanation for his emotional reaction, only to find that it can’t be properly articulated. In one scene, Karl Ove has boarded a plane to go see his father’s body, and finds that he can’t reconcile his train of thought with his grief:

Everything I saw, faces, bodies ambling through the cabin, stowing their baggage there, sitting down, was followed by a reflective shadow that could not desist from telling me that I was seeing this now while aware that I was seeing this, and so on ad absurdum, and the presence of this thought-shadow, or perhaps better, thought-mirror, also implied a criticism, that I did not feel more than I did +

Of course, shortly thereafter he bursts into sobs and laughter as the airplane takes off, and continues to cry while being aware of the woman next to him stonily staring into her book.

This and other moments in My Struggle are not a retelling of memory as much as a transcription of it, and the experience is strangely compelling. It is an outpouring of anything and everything that Knausgaard associates with a given moment in time, and the feeling of reading it is somehow purgative. Much of its strength comes from the absence of typical novelistic “shaping” of the author’s experience: in the same airplane scene, after his outburst Karl Ove notices the book that the woman is reading and absurdly remarks to himself, “I had read it once. Good idea, poor execution.” His adult reflections are filled with doubts, hesitations, asides, and intellectualizations that circle around events and seem in tune with our own often-uncertain reception of events in real time.

However, in the first section of the book, Knausgaard’s childhood, the outpour competes less with the intellect. His childhood is suburban, middle class, and largely uneventful. Karl Ove plays in an untalented band, slacks off in school, has different short-lived crushes on girls in his class, and sneaks out of the house on New Year’s Eve to get drunk. A great deal depends on the reader accepting the importance of the access to these thoughts as much as the thoughts themselves, as if Knausgaard has presented a diary, one written simultaneously for himself and for you. Here is a typical example of Knausgaard’s attention to the detail of the past:

This evening, the plates with the four prepared slices awaited us as we entered the kitchen. One with brown goat’s cheese, one with ordinary cheese, one with sardines in tomato sauce, one with clove cheese. I didn’t like sardines and ate that slice first. I couldn’t stand fish; boiled cod, which we had at least once a week, made me feel nauseous, as did the steam from the pan in which it was cooked, its taste and consistency. I felt the same about boiled Pollock, boiled coley, boiled haddock, boiled flounder, boiled mackerel, and boiled rose fish. With sardines it wasn’t the taste that was the worst part — I could swallow the tomato sauce by imagining it was ketchup — it was the consistency, and above all, the small slippery tails +

This continues. No memoir is free from an amount of situational detail, which confers a sense of authenticity to the moment as it was lived. The same type of description is commonly seen in a great deal of fiction, a mimetic gesture that helps make things tangible. Knausgaard’s intent is not merely to make a gesture, but rather rather his goal is to fill his account of life with as much of this type of detail as possible. Like automatic writing, it becomes the key that returns the meaningfulness to moments as the sense of proportion between the “important” and the “unimportant” is lost.

The adult Knausgaard implies that this method is what has made the book possible, but he couches this admission in an unusual way:

For several years I had tried to write about my father, but had gotten nowhere, probably because the subject was too close to my life, and thus not so easy to force into another form, which of course is a prerequisite for literature. That is its sole law: everything must submit to form. If any of literature’s other elements are stronger than form, the result suffers +

Knausgaard is only able to complete a book about his father by refusing to reincorporate him into a typical novel. The memories must be exhumed exactly as they are, without the restructuring of a “classic” literary form. But not without form altogether. The torrent of memory requires a supplement, the thoughts of the mature writer, to keep it coherent and give it the form it requires.

It would be a mistake to attribute the interest of Knausgaard’s work solely to its transparency or essential truthfulness. It is certainly not the first work to assume the mantle of complete correspondence between characters as they appear and as they are in the world, while maintaining a loosely “novelistic” structure. For Knausgaard the transparency has a purpose in mind, and relates back to the idea of finding the meaning in things. As the second part of My Struggle begins by recounting Knausgaard’s attempt to write his second novel, the work is lifted into a more rarified aesthetic argument. Knausgaard implicitly acknowledges the somewhat unfashionable nature of this line of thought, aligning his interests with pre-20th century painting and its goal of representation. He writes movingly about a Rembrandt self-portrait he admires, describes his strong but ineffable feelings as he flips through a book of Constable paintings. In these passages he gives more insight into the underpinning of his project:

Those…who call for more intellectual depth, more spirituality, have understood nothing, for the problem is that the intellect has taken over everything. Everything has become intellect, even our bodies, they aren’t bodies anymore, but ideas of bodies, something is situated in our own heaven of images and conceptions within us and above us, where an increasingly large part of our lives is lived. The limits of that which cannot speak to us — the unfathomable — no longer exist. We understand everything, and we do so because we have turned everything into ourselves.

The point of this remark is taken in the previous stream of memory; the intellect has been evaded, at least temporarily, by simply taking up the act of accurate representation, as one might paint a landscape. We can try to have experience without thinking about experience.

Knausgaard doesn’t ask you to identify with the details themselves, but instead to investigate your own private memories and to share in the commonality of having your own unique experiences. How did you feel about your childhood meals? What records did you listen to as a teenager? The feeling of those moments is not based on the experiences themselves but instead an invitation to share in the kind of experiences they are. The effect can be almost hypnotic, as recollection after recollection passes in front of you, almost casual but full with the residue of fact. It is like being let in on a secret, but ultimately the secret revealed is a window into the specific experience of another person.

Yet there is a fragile tension here. Looking for the thread of non-intellectualized experience seems deeply at odds with a work that is willing to ruminate at length on (and quite abstractly) on the search for meaning. At the same time, it doesn’t seem as if the outpouring of memory could survive without these types of essayistic passage to provide context, to situate them in a framework that keeps reflections from simply being an undigested catalog of thoughts. And once the above passage has been read, hasn’t the book’s project of creating meaning by transcription become an instrument of a more reflexive, even intellectual, project?

But this is no great contradiction. The importance of Knausgaard’s work lies in the ability to engage honestly with his subjects: as a thinking, educated person, he would be remiss to suppress the intellectual mechanism that is constantly spinning in his mind. A completely unmediated experience would be a deception, a literary artifice just as deliberate as the taking of novelistic liberties. The objective then is a balance instead of a synthesis, a method of contrast and separation between our thoughts and our experiences that attempts to preserve each.

In the work’s second section Karl Ove and his brother spend a great deal of time preparing the funeral and cleaning the house in which their father died, leaving behind a deep record of decay and filth. As he systematically scrubs the trace of his father form each room, Knausgaard recognizes the inevitability of meaningful experience in any life, and these moments naturally become reincorporated back into Knausgaard’s question of form and meaningfulness. Scrubbing away the layers of decay left by his father needs no intellectual foundation, but an intelligent person can (and inevitably will) provide metaphorical significance for the situation.

Knausgaard bookends the work with some reflections on death, imposing one final boundary of form by meditating on the event in life that, according to Knausgaard, makes its form most apparent:

For humans are merely one form among many, which the world produces over and over again, not only in everything that lives but also in everything that does not live, drawn in sand, stone, and water. And death, which I have always regarded as the greatest dimension of life, dark, compelling, was no more than a pipe that springs a leak, a branch that cracks in the wind, a jacket that slips off a clothes hangar and falls to the floor +

In the end the circle between meaning and form is closed. For Knausgaard, death gives form to life by providing a terminus, a common boundary, just as each inanimate object has its own properties. But moreover, the strength of death as a form lies in its inability to be thought: as much as we’d like to make death merely intellectual, we cannot do so. The ceasing of experience is the definitive sign that we must attempt to hold onto whatever experience in life we can, whatever that life may end up being.

]]>

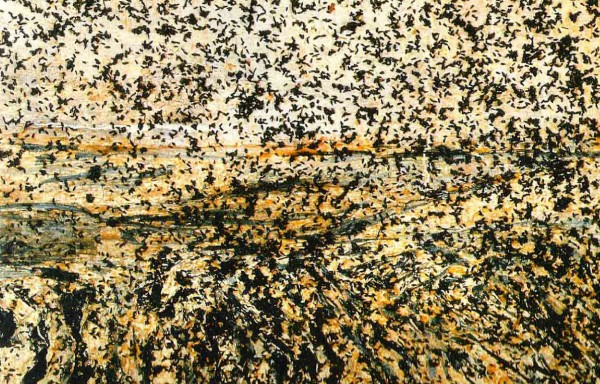

César Aira. Courtesy of Center for the Art of Translation.

An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter by César Aira. New Directions.

The Literary Conference by César Aira. New Directions.

How I Became a Nun by César Aira. New Directions.

Ghosts César Aira. New Directions.

The Seamstress and the Wind César Aira. New Directions.

Varamo César Aira. New Directions.

The recent import of new generations of Spanish-language authors into English has been a significant gift for readers. The spearhead of this development, of course, was the entrance of Roberto Bolaño into our literary consciousness, and it is worth briefly considering why the Chilean has made such a large impact in his relatively brief stay in our discourse. For one, he shows us a new picture of world literature as completely cosmopolitan (2666 in particular seems to work extremely hard to establish this fact), a landscape in which we are all exiles from the republic of literature. Nevertheless, Bolaño and his stable of fictional authors work to recover the idea of literature in a world that continues to do its utmost to destroy such a notion completely.

This second aspect, I think, is near the wellspring of Bolaño’s widespread popularity: the earnest reopening of certain big-picture questions about the place of literature in the contemporary world, a line of questioning that some of our more familiar avant-gardes have attempted to suppress, bypass, or at best approach only very obliquely. The other authors who have been pulled into English by the force of Bolaño’s inertia share this concern to greater or lesser degrees, including Enrique Vila-Matas, Javier Marías, and finally, César Aira. Each of these authors offers us a potential antidote from a creeping sense of paralysis in the fiction of our own language. Critics who are prone to decry the impossibility of truly understanding literature in translation are blind to the ways that such works constantly reconfigure our sense of what is possible. One reads these authors with a wide view for difference and similarity, as if watching a person with a completely different skill set try to solve a problem for which we would never have imagined such tools used.

Aira is an attractive author, but he is perhaps the most difficult of all of the above mentioned. This is not because his prose is particularly dense or difficult to understand, but instead because of his attitude toward literature, which seems alternately ironic and playful to the point of indifference toward literature as a “grand” pursuit. Each novella feels like an experiment in the most basic sense of the word (it is not for nothing that Aira construes himself as a mad scientist in The Literary Conference), where anything created can be annihilated just as easily, including the markers of literary greatness.

This betrays one difference from Bolaño, who even when he castigates literary authors or “literariness” is tacitly celebrating such conceptions. If Bolaño’s appeal is based on the construction of a myth of authorial greatness, the links of which endlessly (and perhaps fruitlessly) forged in darkness, Aira offers us something very different. Aira is rather more of a conceptualist, a unique variation on the tradition of a Latin American literature of ideas, following in the Argentinian vein of Borges and Cortázar.

Aira is known as a prolific writer of novellas, most of which remain untranslated, and for his distinct method of composition. Any discussion of Aira must return to his method. Almost every piece written about Aira so far concentrates on his unique sense of “fuga hacia adelante,” (flight forward) in which his novellas veer wildly from one topic to the next from page to page. It is said that he rarely revises what he has written. Each novella has at least one development that simply could not have been guessed by a first-time reader. It could be the attempt to clone Carlos Fuentes, disfiguration by lightning, the sudden personification of an amorous wind god, a reflection on the rare appearance of dwarves, attack by giant blue silkworms, or the revelation of an illicit golf club racket in Panama. All of these incidents pass by in the space of a few pages in their respective works, their brevity compounding their strangeness. One of Aira’s selves, the surrogate-Aira of The Literary Conference, puts it this way:

Hyperactivity has become my brain’s normal way of being. […] In my case, nothing returns, everything races forward, savagely being pushed from behind by what keeps coming through that accursed valve. This image, brought to its peak of maturation in my vertiginous reflections, revealed to me the path to the solution, which I forcefully put into practice whenever I have time and feel like it. The solution is none other than the greatly used (by me) “escape forward.” Since turning back is off limits: Forward! To the bitter end! [26-28]

But what exactly is Aira attempting to escape? The “hyperactivity” mentioned before does not refer to the novella’s contents, which are certainly varied and quite active. It instead refers to the problem of possibilities that the author faces. For Aira the construction of the novel is essentially a problem of contingency. Is there any truly necessary sequence of action or continuity for fiction any longer? If the novel begins to become boring, why not simply uproot it and introduce a new subject? Or simply end it before it becomes too long? The flexibility of fiction is being tested, and Aira generally intends to see how far it can bend before it breaks.

It’s worth asking if contingency is simply a given from where we start out as modern readers. We live after the period of radical questioning on the subject of literature’s structure, order, origin, and acceptable vocabularies. I don’t think it would be unreasonable to assume that we have become inured to range of potentialities on display for contemporary fiction writers. Often this situation is formulated as a standard dichotomy: the choice for many, it seems, is either to write a type of postmodern fiction that acknowledges pervasive heterogeneity, or to continue to plow forward as if the break never happened.

Aira belongs to the former category, but with somewhat of a twist. He is not the first to inject complete, radical disjuncture into narrative. His natural forbearers are Roussel and Breton, both of whom are mentioned by name in his work. Aira’s own method lies somewhere in between the programmatic experimentalism of the former and the unconscious flow of the latter. However, what makes Aira’s novels distinctive is that as one continues to read him, eventually adjusting to the pace of his writing, his ruptures begin to seem like means toward something and not as ends in themselves.

This is not to say that older writers simply fetishized their own disjuncture (though at times they did) or that Aira is completely free of the same crime (The Seamstress and the Wind, while enjoyable, is the particular culprit here and the maybe the weakest for it). It is to say that Aira’s work recognizes the tangent as a given, a starting point instead of a polemic to be made against an existing system of order. Nor does Aira’s intention seem to be to antagonize or “challenge” the reader; generally, his prose remains straightforward, alternately like someone unconcerned with such problems or someone in a hurry to get to the point. Instead of anxiety, it is a celebration of fiction as an open field of possibility. The difference in emphasis is small but significant.

Consider Aira’s Ghosts, one of Aira’s most accomplished works. The novella recounts the New Year’s Eve of a family who live in an incomplete condo complex in Buenos Aires(the father is the night watchman for the construction company), drawing a beautiful portrait of their daily minutiae and familial relationships. True to Aira’s way, the complex also happens to be haunted by a swarm of fleshy and naked male ghosts, who seem to have attained their ghostly whiteness by the addition of a layer of supernatural flour. What makes the arrangement work is how skillfully Aira manages to normalize the juxtaposition. The “shock of the new” wears off within the first thirty pages; we become used to the premise, and Aira moves on to stranger and more beautiful combinations, including an extensive dream about architecture and Lévi-Straussian anthropology that sits like a marker in the center of the novella.

The description of “escaping forward” is also not as straightforward as it seems at first glance. To say that Aira simply flies forward without a thought for what has come before would be to mischaracterize the construction of each novella. Each work develops subtly, returning to points found earlier in the text, and demonstrating structure even if that structure is loose. This is perhaps the second key element of Aira: there is no absolute, even of contingency. Any line can be erased and redrawn.

Take for instance, in Varamo, where a piece of candy that the eponymous character bought distractedly in the novel’s early pages returns as the novel’s final poetic image as the center of a vortex of birds pecking at the candy. To be sure, this is a literary joke, as Aira notes accordingly: “This struck Varamo as interesting and poetic: a ‘writerly’ experience. For him, everything was ‘writerly’ now.” [88] However, neither is the joke really deprecating: there is something still meaningful about the “point at which they all converged”, even if its foundation is ultimately arbitrary.

Aira’s deviation from the (now nearly extinct) “norms” of fiction is generally concerned with aspects of what I’ll call “fictionality”: language on the level of the sentence, in contrast to many modernists, is not the main point of inquiry. Instead, plot, degree of realism, types of description, characterization, and symbolic vocabulary become Aira’s tools for manipulation. There is a deep sense of the author at play, finding pleasure in the connection of disparate ideas not because they are disparate, but because something is always found in the connection. A figure for this appears in How I Became a Nun, in which the child César Aira invents an imaginary world of pedagogy. Random rules are given to imaginary children in a system that becomes increasingly complex:

It got to the point where everything I did was doubled by instructions for doing it. Activities and instructions were indistinguishable. […] How to manipulate cutlery, how to put on one’s trousers, how to swallow saliva. How to keep still, how to sit on a chair, how to breathe! […] I took it for granted that I already knew everything. I had mastered it all . . . that’s why it was my duty to teach . . . And I really did know it all, naturally I did, since the knowledge was life itself unfolding spontaneously. Although the main thing was not knowing, or even doing, but explaining, opening out the folds of knowledge . . . [87-89]

This exercise is both a game and a poetics of universality. All life unfolding is a subject for recounting, a jumping off point into something more elusive, more difficult to explain. There is an implicit claim: because anything can become an interesting subject once investigated or “explained,” there is no hierarchy of literary value here.

It is exactly the democracy of this contingency that feels liberating. Aira’s symbolic or imagistic vocabulary is difficult to recount because it is almost completely mutable. Any topic or object can be fashioned into a bridge to a new discovery or relation. A catalogue of all the repeated motifs in Aira’s novellas (many of which are shared between volumes) would be exhausting, and ultimately somewhat uninformative. A good example would be the gigantic tractor-trailer in The Seamstress and the Wind, in which the seamstress finds an endless number of rooms to wander through: each is evocative and interesting, but the sense of infinite extensibility is the true quality exhibited. Even genre is not safe from this endless mutation, from the historical fiction of Landscape Painter to the science fiction of The Literary Conference to the exploded autobiography of How I Became a Nun`. The capriciousness of this is often explicit:

“I’ve been looking for a plot for the novel I want to write: a novel of successive adventures, full of anomalies and inventions. Until now, nothing occurred to me, except the title, which I’ve had for years and which I cling to with blank obstinacy: ‘The Seamstress and the Wind.’ “ [3]

Any writing that works against the grain must discover a way to be explained. This may come from criticism proper or from a criticism articulated from within the work itself. Aira provides the latter, as each novella involves some account of artistic creation, but with a very large caveat. Is this self-referential poetics merely another key in which the versatile fiction writer finds himself able to play? Normally, when a work takes the reader aside to describe its own mechanics, the reader can rest easy knowing that he or she has found a governing idea behind the work. For instance, when an author places the dilemma of an artist at the center of the work, we are both informed of the hierarchy of values (the creation of art stands at the top) as well as given a microcosm of the work’s creation. In Aira we are given microcosms that may only exist because they are interesting and not because they represent any larger principle.

For instance, Rugendas, the main character of Landscape Painter is dedicated to a process described as “physiognomic “ landscape painting, a technique that provides the benefit of “conveying information not in the form of isolated features but features systematically interrelated so as to be intuitively grasped: climate, history, customs, economy, race, fauna, flora, rainfall, prevailing winds …” [6] Besides belonging to the running joke of Aira’s tendency to describe things that cannot actually be visualized, the description tempts us toward a superimposition of Rugendas’ painting and Aira’s own work. However, we’re quickly lead astray by Aira’s flight forward, and the idea of using Rugendas as a figure for Aira’s process of creation becomes increasingly tenuous. Rugendas comes from a line of painters well known for their depictions of battle scenes. At the end of the novel, Rugendas is returned to this function as he manically draws a battle between natives and settlers near an Argentinian outpost. Doubtless there is a significance in the comparison between Aira and Rugendas, but as the example is folded back into the fiction, complete with corollaries and details, the parallel becomes increasingly difficult to draw.

Another example is Aira’s digression in Varamo, in which he discusses the “avant-garde” in literature:

The poem’s capacity to integrate all the circumstantial details associated with its genesis is a feature that situates it historically. It doesn’t possess that capacity by virtue of being an avant-garde work; in fact, it’s the other way around: it’s avant-garde because it makes the deductions possible. It can be said that any art is avant-garde is it permits the reconstruction of the real-life circumstances from which it emerged. While the conventional work of art thematizes cause and effect and thereby gives the hallucinatory impression of sealing itself off, the avant-garde work remains open to the conditions of its existence. [45]

Varamo is framed as a piece of literary criticism that attempts to explain how a Panamanian bureaucrat wrote a masterpiece of 20th century poetry. This account of the avant-garde seems sound on the surface, but is highly questionable in the larger context of the novella. Not only is the work itself never described (how could we verify the assertions?), but the whole work is in fact a thematization of cause and effect, describing precisely, to the point of absurdity, the necessary events that caused the work to be created. It is a parody, but the novella’s pleasure derives exactly from the tendency that is being scrutinized. Each novella seems to prescribe rules of fiction only to expose their futility.

But what makes all of these flights and contortions more than a mere exercise? With the contingency of form, subject, and artistry already made explicit, Aira loops around to interrogate the idea of fiction as a work that reveals something about life as it is experienced. The recurring question for so many characters in these novellas is an emphatic and unanswered question of “Why me?” Rugendas asks it after he is hideously disfigured by lightning halfway through his adventure. Delia, the seamstress of the book’s title, asks it as she is vaulted endlessly through the sky into a Patagonian moonscape. Patri, the quiet homebody of Ghosts, asks it before she is inducted into the glowing festival of ghosts.

There is a sense of Aira as the indifferent god who subjects his creations to difficult situations, but there is something more than that. The real contingency of our lives is reflected in these works, the ways in which we are constantly found to be powerless against the stream of events. This has the double effect of underlining the ways in which fiction transforms the contingency of our lives into necessity: the classic novel is an isolated work, frozen and perfected in its architecture. Things must have had to happen that way, we think. Perhaps we are attracted to traditional, formally symmetrical stories exactly because they encourage us to see our lives in the same way. We take in stories like a cure, looking for our own symmetry. In Aira we find a world that is as haphazard as our lives, but are instead encouraged to create our meaning in the cracks, forging the relationships and significances ourselves. And literature takes on again a new power, as Aira is always free to begin again, to write the novellas in which all the possible alternatives happen.

For decades now, the most prominent place in our literary canon has been awarded to the monolithic novel, a work that attempts to give the impression of containing all topics within its pages. Modernist epics like Ulysses or The Magic Mountain set out to create total pictures of their world, or at least capture in art (momentarily) the unity that seemed so lacking beyond the domain of literature. Even the generations of large postmodern novels following in that wake, from The Recognitions onward, seem to champion and pursue that unity while simultaneously avowing its impossibility.

Maybe then Aira’s preferred format, the novella, is a type of literary humility. His work, when considered in total, creates a body of work that is similarly vast, filled with digression, disjuncture, and juxtaposition, but the decision to occupy a series of books around 100 pages feels like a small literary joke: another author might simply have labored several more years to thread together these six novellas into one large, “definitive” novel. Aira leads us toward a realignment of values in our literature, where representing totality is unnecessary. Instead, we are encouraged to find value in surprise, the free play of ideas, and a rejection of the rules that we supposed shackled authors. As we continue to fly forward, we continue to find something new.

]]>