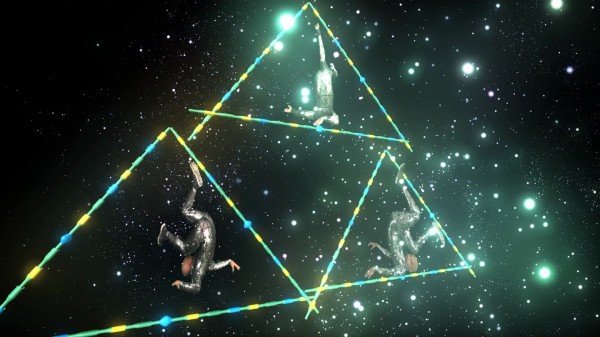

still from Satterwhite’s Reifying Desire 5, 2013. courtesy the artist and Monya Rowe Gallery, New York.

Jacolby Satterwhite is not very interested in seeing the end of the world– at least when it comes to the world of Final Fantasy IX. He and I are nested in the nook of a quiet coffee house, perfectly off-task in our discussion of the famous role-playing game (RPG) franchise.

“Which one’s your favorite?”

“Six, seven, and eight. Actually, nine is really good too. I actually got to the fourth disc on nine in like four days, and I quit, I didn’t ever beat it. I just went outside and said, ‘ I want a boyfriend!’”

The Matriarch’s Rhapsody, on exhibition at Monya Rowe Gallery through February 16, is a show that resonates with the inner RPG gamer. Perplexingly digital, the solo debut is well versed in fantasy, offering up a fizzing, disoriented world full of CGI animation and cavorting indiscretion. The hybridist result of collaboration, Satterwhite’s work takes impetus from his mother’s drawings, the sketches a means of dealing with a lifelong diagnosis as schizophrenic. Often multi-purposed, her designs for inventions resemble those of an infomercial, as her creations anticipate the inconveniences of daily domestic life and seek their ease. There are designs for a hanging pot rack, a guitar, slicing trays for meats and cheese, barbeque grills, lighters that “are dress designs too.” Her most notable works deal with bodily image: crafted outfits “for the fat body,” elaborate bodysuits with scented pads for the breast, waist, and genitals — areas “under the belly near the cock, the hot spots.”

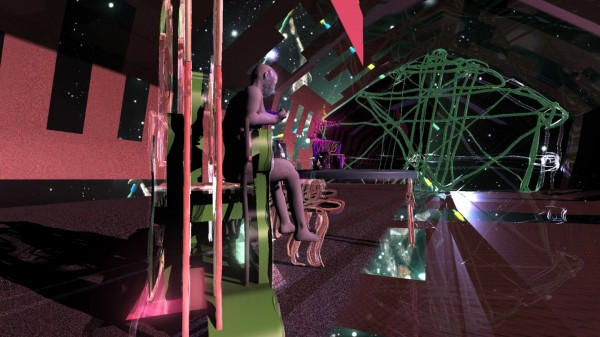

still from Satterwhite’s Reifying Desire 5, 2013. courtesy the artist and Monya Rowe Gallery, New York.

Using these representations as launch pad, Satterwhite constructs his own animated universe, incorporating modern dance, voguing and ballroom culture to make sense of the drawings, and their attempts to fulfill notions of the modern ideal. While Satterwhite’s maximalist tastes appear unhinged, this is not due to a disinterest in academic formalism. Earning an MFA from UPenn, and a BFA from Maryland Institute College of Art, Jacolby worked eleven years as a painter before his interests turned to performance and modern dance, and eventually, CGI animation.

“I used to always work with my mother’s drawings as prompts for inspiration. If she made a drawing about football, then I got some football equipment from some weird place and did something with it. So, I started playing with after effects and I taught myself Rotoscoping and all these tricks — I figured out that in tracing the drawings I could eschew the lines and make them 3D. Once I figured out I could make her drawings 3D, I started working like crazy. Just stayed up all night, didn’t sleep, just read books and did tutorials. It happened organically… Voguing came into play because, I understood my mother’s drawings were design objects, and voguing houses often try to mimic a more Western, patriarchal American lifestyle, like wearing Louis Vuitton and Chanel. My mother’s trying to subscribe to an entrepreneurial lifestyle — I’m kind of functioning as an apprentice of her, carrying her vision into the world. So, voguing felt right, like a kind of tongue and cheek thing.”

As Sorcerer’s Apprentice, the artist viscerally unites his mother’s visions with his own body. Bedecked in a metallic bodysuit, the only human in his compositions, Jacolby’s “live” presence is incendiary. As he vogues, his jabs, angles, and rotations bring agency to the Reifying Desire videos, his movements literally bestowing life, aid, or complete destruction to its players. “When I do that in front of the green screen, I basically composite what I was envisioning in my hand and the space around me. I trace every limb from the computer, and so I can attach objects to them. When I put the characters all over the landscape, I can lineate the storyline from that. It starts out super loose, in my movement. The objects and the technology kind of synthesize the narrative on its own.”

While Satterwhite’s narrative may come off rather shadowy to his audience, the work is far from aimless. His Reifying Desire series is a suite of six videos, the fifth of which is on prominent display at Monya Rowe. When watched in succession, the videos make up six “chapters” of a loosely knit narrative, telling of the spastic creation, evolution, and obliteration of Jacolby’s amorphous world. Each video is an elastic rumination on a theme, their end a variation on the Alpha and Omega, the Christian tell-all symbol of the beginning and end of days. His settings too, are concerned with classic religious imagery.

“I’m interested in a lot of images form the Renaissance compositions, like high and low registers. For some reason, specifically older Renaissance painters, like Titian, where he had the Madonna and Child in the heavens, separated by clouds, and then the regular people standing on the ground, and its divided by clouds. I think that CGI animation would be the heavens in an ideal world, a sphere of falsehood or something. My performance in real space is sort of a representation of alternatives, and making those worlds bleed together.”

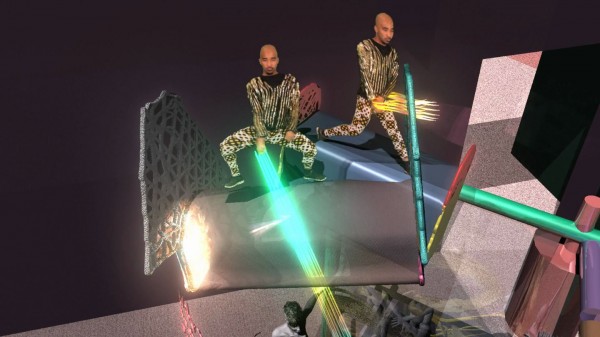

still from Satterwhite’s Reifying Desire 5, 2013. courtesy the artist and Monya Rowe Gallery, New York.

Though when I suggest his celestial backdrops reflect a heavenly quality, he’s hesitant to agree.

“I wouldn’t say they’re heaven or utopian. Well, they are kind of, because it’s kind of like what I want to see happen. The absence of race, the absence of anything political. But it’s inherently political also. It’s a place of folly, and pictorial exploration. Honestly, [it’s] everything I wanted to do as a painter, but it’s moving. The kind of space I wanted to articulate had this whimsy and weirdness.”

As he and I review his videos, our talk turns increasingly spiritual. A neighboring café dweller feels the need to interject. He sets a book on our table.

“You see this? Your computer?” he says, pointing to a line in his book.

“The computer’s number is 666.”

“What does that mean?” Jacolby insists, and is met with silence. Without skipping a beat, he turns back to his iPad and smiles.

“Speaking of that, you’ll see here this image begins to turn into these cruciforms.”

This real-world imposition clarifies Satterwhite’s intent for his sprawling visions. He’s most interested in confounding reality, in creating a landscape so bewildering that any number of dreams can take place in its scope. For Jacolby, it’s a world so irrational that it holds the potential to absolve any grand socio-political statements viewers might demand of it.

“You know I often tell people that another strategy in performing in a virtual space as a black performer is a way to remove the potential for politics…everything is removed from its original context with reality. So, it just takes the term ‘queer’ to another level. It’s not about gay or straight, but queering meaning, de-contextualizing things out of a normal space. This is definitely an anti-normative sphere.”

still from Satterwhite’s Reifying Desire 5, 2013. courtesy the artist and Monya Rowe Gallery, New York.

Reifying Desire 5, the eight-minute video that travels the fate of five cybernated women, is certainly unconcerned with normality. The work is a composite of two influences: posing as Picasso’s infamous Les Demoiselles D’Avignon (1907), and one of his mother’s drawings entitled, Pussy Power. Detailing a number of lotions, gels, ‘lipsticks’ and ‘flavors’ designed to eliminate feminine odor, her instructions are as follows: “For pussy power, pour bubble into the hot water and soak for awhile to turn the smell of pussy off.”

What ensues is a swirling rumination on feminine sexuality and beauty upkeep. In a walled, domestic setting, five sprouts of pubic hair take center stage. The cubist’s painting floats amidst the madness, as Satterwhite’s visage infiltrates the space, setting the hairs afire. The clumps burn away, transforming the sprouts into lanky, mannequin-like figures. Fully blossomed, the female figures bathe, pose, and luxuriate in Jacolby’s attention, as he administers the potions for pure, unadulterated ‘pussy power.’ The women merge, bend together, then part. The hair on their heads grows and merges into one expanding, ropey mass. The women undergo a series of divinations before developing male genitalia. The video scene climaxes, quite literally, as one woman’s phallus shoots millions ‘mini’ Jacolbies into the world. Rioting around the space, the Jacolbies spread and infect, until they’re eventually consumed, then expelled from the scene, pitching the domestic setting into a nebulous, galactic sweep.

The decision to model Reifying Desire 5 after D’Avignon is an interesting one. A shock-and-awe masterpiece, D’Avignon propelled Picasso to unimaginable infamy — its place in the canon marks nothing less than a watershed moment for modern art. The painting’s “primitive art” influence, the African masks for whores’ faces, all offer a flagrant refusal of European influence and “insider art,” altogether. Moreover, and maybe most appealing to Satterwhite, is the refusal of anachronistic rules at the expense of the female form. As John Berger said, “A brothel may not in itself be shocking. But women painted without charm or sadness, without irony or social comment, women painted like the palings of a stockade through eyes that look out as it at death — that is shocking.”

Satterwhite inverts D’Avignon’s female distortion to its opposite end, digitally perfecting Picasso’s five fractured bodies. While the modelesque women symbolize a bodily distortion of their own, they reflect a demand to be rebuilt, ‘fixed’: “in being queer, with a mother with mental illness, I think wanting to be fixed can become a motif that reoccurs in my work.”

Between the bravado and bawd of Satterwhite’s expanse lives the silent ache of traumatized bodies — of bodies, which, in real life, have learned to be insidiously self-aware of their standing in the world. This is evident in the compensative bravado of the vogue dance, in the gyrations of the cyber-women, and most emphatically in Pussy Power itself — the decision to gain advantage through a cleansing of offending female parts.

still from Satterwhite’s Reifying Desire 5, 2013. courtesy the artist and Monya Rowe Gallery, New York.

Satterwhite’s figures demand an existence where they are not considered defunct — so much so that the parameters of what “fixes” a body dissolve, the question of what a body is as fluid and indeterminate as Satterwhite’s loopy terrain. This disparity between body confidence and body consciousness is what brings Reifying Desire 5 into elevated relief. It also gives Satterwhite’s videos a feeling of suspense, of inclement rising action. As the animated world elicits the potential for limitless possibilities, the viewer wonders, will any of these figures really get what they want? At the moment, Jacolby’s wants are in transition. Recent reviews in The New Yorker and The New York Times bring a re-assessment of his goals, and a concern for his practice and himself. I ask him how the recent praise of his work feels, and he takes his time to answer.

“I’m starting to figure out what that means. It’s weird — you think when you get opportunities like this that it will feel great, and it feels great but it’s also very vulnerable. My drawings are everywhere, and it’s explicit, and I feel so naked with that show. Like that show is embarrassing, it’s so naked. I made a degenerate, crazy show. But the thing I like about that show is the blurring authorship, you can’t tell if I’m the misogynist or she is. I know how people criticize male artists, saying, “that’s very male,” the way you frame the female body. It’s not my drawing, but imagine if I had made the drawing called ‘Pussy Power?’”

The Matriarch’s Rhapsody is a reflection of the wants and needs of both mother and son, not only in its sensuality, but in its hunger for consumerism that pervades. These urges are not necessarily pretty, the visuals not thoroughly digestible. But they are honest — like most desires they are desperate, wild and brutal. And it’s true — as Jacolby blurs the authorship between himself and his mother, perceptions begin to bend, and so their mutual and disparate needs hybridize. This blending builds into a chorus that is unflinchingly human — a commiseration in the lifelong urge to make oneself in the image suggested for us.

This realization is indeed bleak, but fortunately, Satterwhite’s purview is still that of a gamer’s, and the gamer refuses fatalism.

Instead, the gamer understands that magical phenomena should not only be expected in play, but seen as the welcome reminder of one’s advancement and progression. The gamer understands race, class, and gender as merely the indefinite ordering of characteristics, all equally useful in the battle to save the game’s world. And the gamer knows that, yes, maybe there’s a satisfaction to seeing the end of the world — all the ugliness of its demise — but this is only because you beat the game. The thrill of the world’s end is great only because you saved it.

Jacolby Satterwhite’s The Matriarch’s Rhapsody is on view at Monya Rowe Gallery, 504 West 22nd Street, New York, NY 10011, through February 16.

]]>

courtesy of Steven R Shook.

Imagine being from a place considered so laudably “cultureless” that even Jon Stewart’s grasping for straws to describe it. In a recent Daily Show skit, pundits were asked what they knew about the two convention host cities. When asked about Tampa, the first response comes from comedian Samantha Bee. After some concentration she finds her answer, “It’s horrible!” she shouts, to big laughs.

I begin with such an anecdote because these kinds of reactions have become commonplace for me, of this year specifically, as my hometown of Tampa, Florida has become a bi-syllabic curse word to thousands. Infamous now as the home for 2012’s Republican National Convention, it’s the battle ground for “The War on Women,” as well as plenty other catchphrases that make my sense of home quiver and flinch at every incoming headline.

Yet, despite the sourness, many anticipate — Tampanians included — that the RNC will prop up our town as a place that finally holds cultural worth — the kind that can be recognized on a national front. We, the city of Tampa, wear many hats, hats of multitudinous style and connotation. The aliases run far and wide: The Big Guava, Cigar City, Lightning (and Strip-Club) Capital of the World, Cigar Capital of the World, and — most precariously –America’s Next Greatest City.

Last week marked the beginning of a full-court press in Tampa’s petition to become that Next Great City. Our being tapped for the RNC has been a tense and exciting confirmation, proof that we’re finally “good for it.” And with the recent stats circulating, (an average household income estimated at 41K, for starters) much design has gone into articulating Tampa as a Safeway for a distinctly “RNC-approved demographic.” If I were to speculate that statistic’s makeup, it might resemble the populace of Downtown Tampa, the backdrop for the convention and the city’s financial center. Home to some of the most wealthy individuals around, it is also one of the most gentrified zip codes in the country, with Downtown’s slickly glitz Channelside holding an over 66% Caucasian residence.

But as I watch my fair city descend the stairs, polished to look as lovely as any Floridian flower, I realize Tampa’s route to become America’s Next Greatest City forges ahead in a time of our nation’s great decline. Plus, the attempt — like any to acquire national prominence — sidesteps the massive pools of people that make us… us. The small percentage of Tampa being lifted up to the world is an outrageous skew of the city. Yet, for anyone from the place itself this sort of cringing irony kind of comes with being a Tampanian — it comes with inhabiting a bayside paradise that is wan and humid and sometimes less-than-bearable.

We’re an experiment of a city. In fact, sprawls of Tampa are leftover experiments in industry, much of the landscape a hotbed of corporate control groups and mission statements. Off-color restaurant chains (heard of the Tilted Kilt?) that hold their own, strange enclaves of patrons, while car dealerships of many disparate brands (one of the first Smart Car dealerships cropped up in Tampa) sit stagnate along the stretch of Dale Mabry Highway, one of the city’s longest roads.

Then there’s the whole strip club thing. It’s quasi-true — the intersections with strip clubs dotting the corners of roads like gas stations. We’ve been labeled a “strip club capital,” and Channing Tatum, of “Magic Mike” success, has based his success on his time in Tampa and Clearwater venues. But we’ve also got The Skatepark of Tampa, a legendary park in the history of skateboarding, a brilliant Museum of Science and Industry, and Straz’s Performing Arts Center, where I saw my first Opera. But since these landmarks don’t serve the political climate, they’ve been overlooked, if not made outright illegal.

As preparations for the RNC began, a number of those strip clubs have been involved in sting operations, and over sixteen women, who’d otherwise be enjoying the constancy of their jobs, were arrested. But the demand for unsavory services in Tampa remain as high as ever. A large number of Craigslist posts for escort services have surfaced, both in search of and in supply of men and women for hire within the downtown area. Other impurities have been similarly scrubbed. Occupy Tampa, though slowly losing steam over the summer months, has all but been disbanded with the onset of the RNC. Most protests of this and other issues surrounding the RNC by Tampa citizens have been ostensibly squelched in media.

Surveillance of my fair city has been severe in almost every aspect. According to an article in the Tampa Bay Times: “the city has now five surveillance cameras watching traffic downtown…hundreds more on the street and in the sky”. I couldn’t be in Tampa for the whole she-bang, so I asked a friend what it’s been like. His answer? “Rain and lots of cops.”

Which is not something we’re totally used to seeing. Crime and its policing has been a serious, though declining, problem within the Tampa Bay Area. Since 1999, our crime averages have creeped below the national and state averages. There’s an exorbitant number of homeless. Tampa holds over 16,000 citizens without homes — the nation’s highest homelessness rate — the same people expected to be earning an average 41K per household. Indeed — of the homeless in Tampa, about 88 percent were already residents of Hillsborough Country before becoming so. Unemployment is at 8 percent, underemployment a higher 16.8%. Portions of Tampa’s neighborhoods have outsized percentages of families living below the poverty line, some close to 30 percent.

And believe me, mum’s the word on the subject of Gasparilla, Tampa’s very own Wintertime Mardi Gras. The event — hosted on the causeways of Downtown Tampa itself — is a dazzlingly florid, areola-flashing affair, organized in the name of one of Tampa’s most infamous historical battle, taken over by pirates in the 1800’s. But this spritely history is all a bit of fabrication. Jose Gaspar‘s only fun legend, and what’s worse, there was never a seabattle for Tampa ‘twixt spurious pirates and city. No one, it seems, has ever really felt the need to fight that hard for Tampa, at least not historically.

The particulars of our history, you could say, have always been a bit tenuous. But, even with such glaring disparity, we’d like, if you’d let us, to get this one thing right. To house roves of people with a grace and aplomb that has never before been associated with us. Nor ever really been allowed us.

And we needed this to go well. But like any city that has been chosen to represent personhood — Olympic London included — the cleanliness of the event does much to sweep the rest of the public under a half-clean rug. It’s one thing to hold our breath for conservative value, but another to do so at the expense of all we’ve done before. In our minds, we’ve always been the template of an average American paradise. Our blemishes and follies mirror those of the nation. Like our country, we’ve tried out every business and enterprise. Things that succeed here succeed with a humbleness and constancy, sure in their routine and surer in their keeping a low profile. What fails here fails loudly, and the abandoned industry that scrolls out beyond Downtown Tampa is left for those less wealthy to care for. In this way we demarcate that very snap that has in recent years, plagued American living — the “have and have-nots” debate that has been swirling now for too long.

This is not meant to air my hometown’s laundry. It is simply one voice from there, with a plea asking that for those in opposition of what Tampa might represent, know that somehow, we are like you. We Tampanians are very much just like you. We’ve giggled at the ludicrous sound of our name, too, plus we’ve probably been the guinea pigs for suburban American trends before they got to you in the first place. Maybe we’re you before you realized who you really were — in the collective sense of course.

The way we see it, we’re a kind of temperate template: a blueprint for what an average American can trust in when they imagine a quiet, humble utopia. Whether that idea has succeeded or failed, we have tasted that side of paradise. We desperately want this to go well — the smiling white caps, the baby kissing, dodging the torrents of that biblical Isaac. Whatever shore the storm strikes, our hope and our optimism will sustain until all of this is well over with, the shiny backdrops have been rolled up. Our dreams for ourselves, persist, in a tradition lots of Americans might understand. We are every bit alive with cultural worth, and it’s my hope that we can rep our grittiness as well as a Patterson, New Jersey or a Detroit Rock City. Until then, we’re an aspirational place — a place you should more than visit. Because our hopes for you are hopes for us, and they stretch over Tampa North and South, eventually pour out to merge with that great, glittering Bay.

]]>

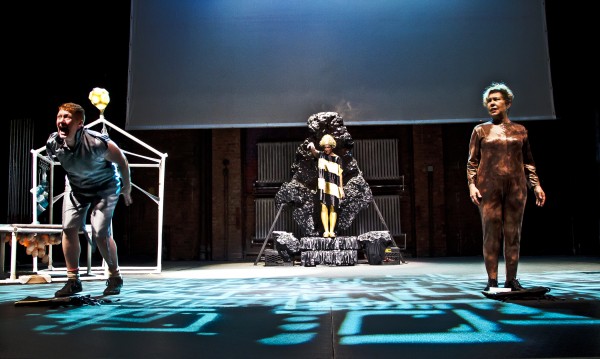

image by Ves Pitts. courtesy of El Museo Del Barrio & Performance Space 122.

Up on 104th street, El Museo Del Barrio’s theater is dim. Its stage is gaunt with white backdrop, lit by glowing props that seem the outcropping of some strange mind’s vision of dystopia. At one end sits a great gyroscopic orb, looking as if it could measure some quality of the future currently immeasurable. Stage left, a primordial cot stretches toward the audience, a net of glowing orbs strewn beneath it’s underside, casting the theater into a wan, curious relief. The more the contraptions are inspected, the more there nature grow exceedingly ambiguous — with one squint they seem entirely foreign, and then suddenly, the familiar sheen of PVC pipe peeks through, recognizable, and any New Yorker’s carping investigation is soon squelched. Ah, these things are made out of trash, the audience realizes. All of this is recycled.

These are the introductory symbols of Post-Plastica, the newest work by Ela Troyano and sister Alina — who is perhaps best known as Carmelita Tropicana, the outrageous, Loisaida-hailing, termagant vixen. Since her debut in the New York art scene of the eighties, Tropicana’s use of camp, comedy, drag and raillery has made her a cultural helmswoman in the exploration of queer Latino and Cuban-American experience. Herself an entity of many shades and fractals, Post-Plastica is similarly a radical puzzle piece of mediums and media — part video installation, part theater play, part performance.

As amalgamated as its parts seem, Post-Plastica is a fable in the strictest sense. It begins with a video introduction of Plastica, or Maggie — a Poughkeepsie-bred, recent art-school graduate turned usurper, played by Erin Markey. After an internship turns to friendship, Maggie parleys the Hispanic artists’ ideas and ambitions into a sudden and tremendous celebrity art career, complete with new and exotic moniker. Enraged with the news of Plastica’s success, a downtrodden Tropicana departs on a fatalistic downward spiral. Hunched over laptop, she imbibes a ludicrous combination of Diet Coke and Mentos before spearing herself with a syringe full of “bad Botox”. The binge sends her into coma, and Tropicana’s image cuts out, replaced with found footage of our present-day techno-revolutions: masses of people huddled together, phones outstretched to record their own happening. “The revolutions are everywhere,” Carmelita ruminates, now disembodied. “The revolutions are Diet Coke”.

Then the screen lifts. Our performer stands to welcoming applause, a massive altar behind her. Arms outstretched, face tilted toward the heavens, she is half- Virgin de Guadalupe, half- Rip Van Winkle. Her body has been sustained well into the future in its comatose state, thanks to the care of HB25, or Ursaan admiring scientist, played by a cool Becca Blackwell. As Tropicana’s character awakens to the future, she immediately chugs out her name in an unpracticed voice: “H-O, Ho.” In their first interactions, Ursa explains that Ho is a relic of the past, infamous in this dystopian future as The Ancient. Like a fossil, her body has been maintained and cultivated to extract information of time gone by, “when animals still existed, when nature had not yet been improved upon”. Ursa’s every move is by direct order of the CEO, the omnipotent ruler of the future. Also played by Markey, the CEO tells of the conditions of her empire, a world literally built on the detritus of our time, “mountains of plastic that have withstood disaster.”

What ensues is a fantastic and laudable journey through worlds old and new. As the CEO grooms her debut to the public as precious artifact, Ho is forced to re-constitute in this dystopia, moving through a kind of infancy. And, true to Carmelita’s form, each milestone is not without a solid ribbing of the socio-cultural normatives that be. As her body thaws enough to become animate, Ho is urged to wear the garb of the future. “Here, put this on,” Ursa encourages, holding up a spangled, bulbous dress. “It’s what all the girls wear these days.” Ho’s language, too, is garbled until again she retains fluency. “I thought she would be speaking in complete sentences by now” the CEO sighs, as Ho spurts outbursts of “gibberish”, a pointed mélange of English, then Spanish, before Ho squeezes out information with stunted consistency. “ I know I sound like soundbite,” she says, explaining this as the favored communication of her time.

It’s no coincidence that this farcical play on language is a conflagration of Troyano’s cultural memory as much as it is comedic stratagem. Carmelita Tropicana the character, was birthed in parts: an aggregate of Troyano’s many “lives” as lesbian, Cubana, performer and artist. Post-Plastica, too, is such a composite; its setting a literal re-structuring of the waste Ho’s world left behind in its ending. As such, this “recycled” world functions with absurd, discordant life– it’s CEO is a fragmented hologram constantly disposed of her body (and at times, her grip on power). Ursa, too, is hybridist: in a comedic love scene between she and Ho, she’s found out to have a tail, forced to explain herself as a twisted half-woman, half-polar bear.

Certainly, Post-Plastica’s aforementioned suppositions and realities don’t rely on a linearity of any kind, nor terribly determined plot or thru-line. This is perhaps to be expected from Troyano if her past work–dizzying in multicultural (“mucho multi”) reference and layering– is to indicate. However, what is masterful about ancient’s interplay is the way Troyano manages to subvert the very legacy that’s made her. In Ho, “the ancient”, lies age and substance organic. It is not the muddling of her background which makes her relevant but the wholeness of her flesh and blood — queerness, nor race or dialect, specify her. Instead, it is her very humanness that is “ancient”, and thus rareified. Her value in this world is confirmed in her existence as fragile mortal. Ho, silly name and all, is miraculous proof of life, non-recyclable–even after the Botox-botched attempt to adorn herself otherwise.

By the piece’s end, Ho and Ursa attempt to rally against the villanous CEO but are thwarted. The stage fades to another video projection. The audience is thrown back into the past, inundated with a collage of warm moments between Plastica and Ho. The video ends with a lingering image of Plastica, teary-eyed and reflective, perhaps even remorseful. She holds a rose tenderly in her hand. Then, belying any too-prolonged sentiment, comically shoves the petals in her mouth.

The lights come on, and the future and its CEO are replaced with Plastica. She stands on stage, moving through a lengthy monologue, thanking both museum and audience for attending what is now suddenly her newest exhibition. In a mind-bending twist, she descends the stage, motioning all to come out to the lobby to view her newest work. The crowd empties the theater to find Ursa and Ho, two parts to Plastica’s newest “triptych”. Ursa stands on marble pedestal with headphones, moving to an unheard beat. Ho flanks her left side in what’s clearly a Hirstian aquarium-cum-moratorium, ostensibly pickled for “art’s sake”. It’s a hysterically grim ending, but as voyeurism and exhibitionism collide in this performance, one recalls that initial phrase: “The revolutions are Diet Coke”. One can’t help but feel Troyano’s Post-Plastica is ultimately a critique of culture’s affinity for preservation — both its merits and follies. Perhaps the revolutions are Diet Coke because the revolutions are mutant, their attempt to preserve, record and make insoluble their presence a kind of dysmorphic failure. Perhaps the revolutions are alight with electric idea, but are eclipsed by their own static, their inability to mold and change into something fundamental, lasting, ancient.

]]>