-

Ghost in the Machine: Hollis Frampton’s Gloria!

by Max Nelson August 16, 2013

…graves at my command

Have waked their sleepers, oped, and let ‘em forth

By my so potent art.

— Prospero; The Tempest Act V Scene 1An Irish ballad written in the mid-nineteenth century tells the story of a drunk named Tim Finnegan, who was taken for dead after falling from a ladder in an alcoholic daze:

[They] laid him out upon the bed

With a bottle of whiskey at his feet

And a barrel of porter at his head.When his mourners get to drinking, the wake devolves into a town-wide brawl: “woman to woman and man to man.” Eventually a flying whiskey bottle shatters just above Tim’s corpse and, drenching him, revives him from death:

Timothy rising from the bed,

Sayin’: “Whittle your whiskey around like blazes!

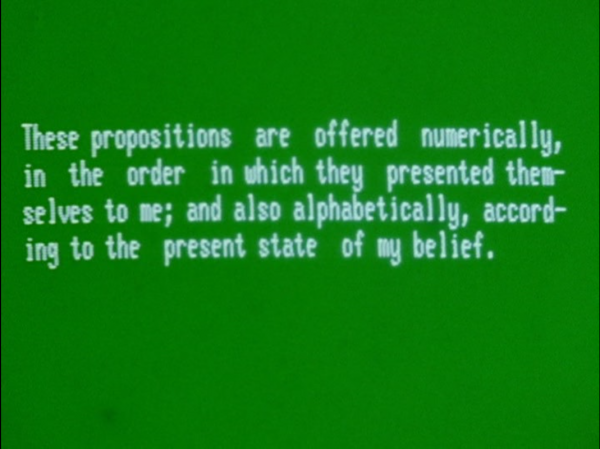

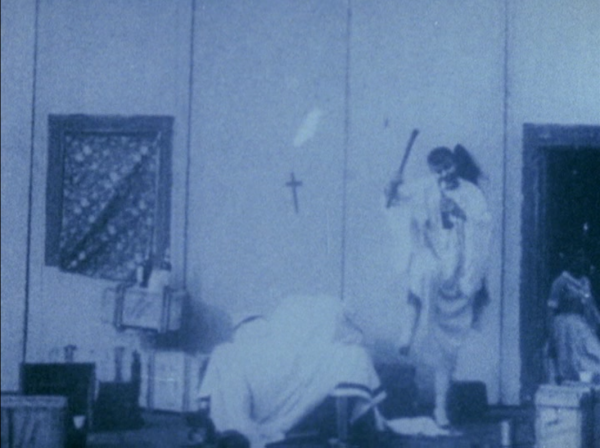

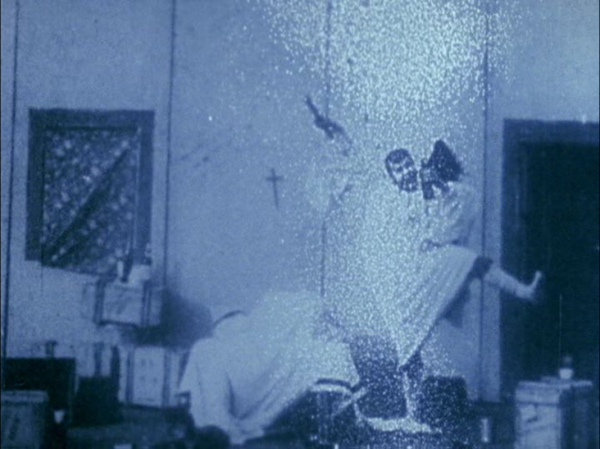

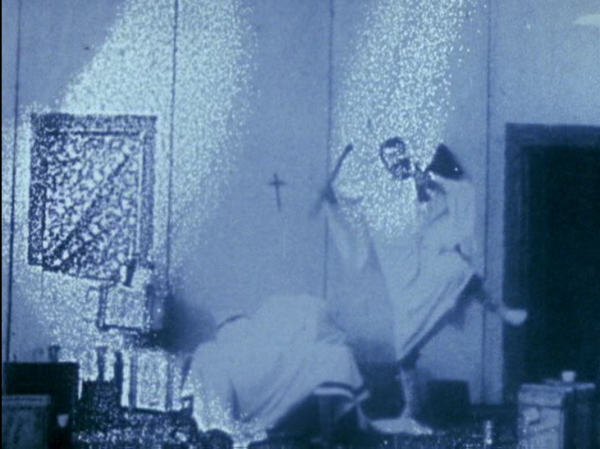

Thanam o’n Dhoul! D’ye think I’m dead?”In the silent-film re-enactments of “Finnegan’s Wake” that bookend Hollis Frampton’s 1979 short Gloria!, the ballad’s story plays out in broad, puppet-like gestures: dancing, weeping, fighting, limb-flailing. When Tim wakes near the end of the final clip, he waves his arms around like a boogeyman and sends his well-wishers scattering away. Left nearly alone in the frame, he kicks the last mourner out the door, raises his fists to the ceiling and leaps around triumphantly, clutching a bottle in one hand and a club in the other. These clips bookend two longer episodes. On a solid green screen, scrolling digital text spells out a series of sixteen “propositions” about Frampton’s maternal grandmother—including that “she remembered, to the last, a tune played at her wedding party by two young Irish coalminers who had brought guitar and pipes.” We then hear, against a now-empty green screen, that same tune played from start to finish.

Gloria! was the last completed component of an intended thirty-six-hour-long film cycle inspired by the travels of Magellan, whose literal attempt to “encompass all human experience,” as Frampton once put it, corresponded to the director’s own compulsion to leave no subject unfilmed, no technique untried, no medium unexplored. The film found Frampton looking forward in multiple senses: eagerly adopting new technology (digital interfaces; computer-generated text) and frankly anticipating his own death. At the same time, Frampton’s circumnavigation of human experience ended up taking him back to his earliest childhood memories, his family history, and the origins of cinema itself. Gloria! begins and ends with a resurrection: a moment when, there being no more future to anticipate, life rewinds itself and begins again.

How is it possible, Frampton seems to be asking, to organize something as elusive and circuitous as memory into sequential thoughts? Frampton’s attitude toward remembrance in Gloria! is almost mathematical, as if the past were a series of facts to be manipulated and derived. At the same time, he’s careful to distinguish between the mushy, vague language with which we often talk about memory and the ambiguities built into memory itself: “these propositions are offered numerically,” reads the first line of onscreen text, typed out in start-stop keyboard rhythms, “in the order in which they presented themselves to me; and also alphabetically, according to the present state of my belief.” The structure(s) of Gloria! are meant to account in equal measure for time as it exists in the abstract—a linear, unbroken, one-way progression of minutes, seconds, and hours—and for time as it’s actually experienced by those subject to it: jumbled, overlapping, doubling back. The tension between these two competing structures is, Frampton suggests, essential to the logic of memory, where every moment exists in theory as a single, unrepeatable entry in a linear sequence, and in practice as something stickier, more resonant, available to be savored and returned to at length.

It’s also, by extension, the logic of the movies, which remind us of the temporal distance separating us from their subjects even as they make the past seem like something tangible and close. It’s possible for us to be so swept away by this second illusion that we forget the fact that precedes it; so taken with a film as it plays itself out in the present, our present, that we overlook its essential point of origin in the past. Occasionally, a cut will cue us into the illusion, remind us that the footage we’re watching isn’t so much a natural emanation of the present as a re-animated, re-assembled product of the past, stitched together from moments of dead time. I’m thinking, for instance, of the abrupt leap in Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln from a springtime courtship to a graveside vigil, or the cut late in Ozu’s Late Spring that displaces a moment of father-daughter tenderness in favor of the daughter’s marriage to an unseen and unloved groom. There is something cruel, final, and decisive about these cuts; they are about the impossibility of clinging to the present and the equal impossibility of returning to the past. Just as Lincoln can never revive his beloved, we can never return to that moment when a young Henry Fonda stooped by a studio-built grave at the behest of a pre-Searchers, pre-war John Ford.

The computer-generated text that occupies much of Gloria! deals in concrete, vivid details: we learn that Frampton’s grandmother kept pigs in the house, though never more than one at a time; that she hailed from Tyson County, West Virginia; that she was obese; that she taught her grandson to read; that she “gave him her teeth, when she had them pulled, to play with”; that she gave birth to nine children, four of whom survived (all daughters); that she was married on Christmas Day at age 13; that, when the filmmaker-to-be was three years old, she read him The Tempest. And yet these bursts of digitized text, even as they point toward a specific point in time, keep that point at a threefold remove: by the time we encounter that woman reading Shakespeare to her toddler grandson, the scene has been filtered through Frampton’s imperfect memory, abstracted into a series of words and phrases, and digitally rendered by a process that further abstracts those words and phrases into streams of numerical data. With Gloria!, Frampton was anticipating a time when information about the physical, time-bound world would be stored outside that world, in an immaterial digital space made up not of ink, matter, or sound waves but digits and pixels. But he was also, I think, encouraging us to consider that scene between grandmother and child as if it existed independently of any one set of digits, pixels, letters, words, or grains, in a space outside of time. The paradox, he suggests, is that such a space—if it did exist—would only ever be accessible to us through a material, time-bound medium.

Shakespeare critics have often taken Prospero’s abjuration of his magic near the end of The Tempest for the Bard’s own thinly-veiled farewell to the stage. If it is a goodbye, though, it’s also a kind of celebration. On Prospero’s part, it’s a statement of faith in the power of the wizard’s art to provoke storms, dim the sun and raise the dead (sixteen centuries after Lazarus and two before Finnegan). And on Shakespeare’s part, it’s a statement of faith in the power of words—if not to resurrect the dead, then at least to call forth their ghosts. The autobiography in Gloria! is both more explicit than that of The Tempest and subject to more layers of ironic distance. Even Frampton’s coming-to-terms with the idea of autobiography is winkingly impersonal: “she convinced me, gradually, that the first-person singular pronoun was, after all, grammatically feasible.” But no amount of tongue-in-cheek detachment or digitally-imposed distance could conceal the flesh-and-blood woman at the film’s center, who once scolded her three-year-old grandson for liking Caliban best out of all the cast of The Tempest, and who lives on in a space where time-bound images blur into computerized text: a brave new world that may or may not also be a world long gone.