-

Self-made Enigma: Raymond Roussel

by Tynan Kogane February 6, 2012

Impressions of Africa

by Raymond Roussel, translated by Mark Polizzotti

Dalkey Archive Press, 2011New Impressions of Africa

by Raymond Roussel, translated and introduced by Mark Ford

Princeton University Press, 2011Raymond Roussel is unclassifiable. To say that a writer defies classification is itself a form of classification — and very often a compliment — perhaps suggesting an agreeable break from orthodox writers or traditions. It seems unlikely that a writer could be called “classifiable” in praise. In many cases — and certainly in this one — unclassifiable also implies that to ignore this writer, or not to read them, would mean missing out on some unusual, arcane pleasure. In some blurb or review, Pablo Neruda wrote: “Anyone who doesn’t read Cortázar is doomed. Not to read him is a grave disease which in time can have terrible consequences. Something similar to a man who had never tasted peaches.” Not reading Roussel isn’t as devastating as missing out on peaches, but Roussel, in his own way, is memorable, unnerving, and shouldn’t be missed. To borrow Neruda’s fruit analogy, not reading Roussel is similar to never having eaten a pomegranate: never having pulled apart the brittle skin, peeled back the bitter membrane, bit into each seed for a tiny squirt of juice, ending up with a red-stained shirt.

Roussel is unclassifiable because he is paradoxical, complicated, and more than a little ridiculous. His literary intentions and his output were at odds: between the two was a misunderstanding, or naivety, that both drove him to depression and ensured him posthumous fame. He wrote for a popular audience, he wanted fame and admiration — to become as popular as Victor Hugo or Jules Verne — but his writing was so difficult that few ventured to read it. However, those who did are an impressive bunch. Among his fans are some of the most important avant-garde figures and movements of the 20th century, including Breton, Duchamp, Cocteau, Perec, Ashbery, Foucault, and Robbe-Grillet, to name just a few. It’s the outspokenness of Roussel’s devotees that has ensured him a posthumous readership, and a place in the peripheral, experimental canon. Recently, two of his major works, Impressions of Africa (1910) and New Impressions of Africa (1932), have been retranslated and republished for a new generation to discover Roussel’s mesmerizing and influential universe.

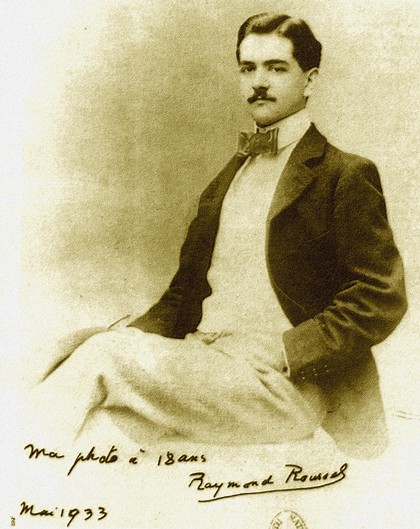

Raymond Roussel was born into a wealthy Parisian family on January 20, 1877 (sharing, an astrologer might note, a birthday with Fellini). His childhood was a period of carefree happiness. He had an indulged imagination, a doting mother (throughout his life he seems to have been a mama’s-boy), and an early talent for the creative arts. After an aborted interest in music, Roussel tried his hand at poetry, and quickly discovered the intoxication of literary inspiration, and the abstract sense of glory that came with it.

In 1896, Raymond Roussel spent six months writing his first book — a novel in verse titled La Doublure — closed off from the world, inside his parent’s mansion. The 19-year-old poet was convinced that he would become the next Hugo or Verne, and while writing, experienced an “intense sensation of universal glory.” Rays of light radiated from him. The words shot out of his pen like a flare-gun. The curtains in his room were closed tight over the windows — a sensory deprivation reminiscent of Proust (incidentally, Roussel’s childhood neighbor) in his cork-padded room — because he worried the light from his pen might escape into the outside world.

La Doublure (which means “the lining” or “the understudy”), composed in Alexandrine couplets, begins as a tale of a failed actor but digresses into a lengthy description of a carnival in Nice — approximately two thirds of the poem, some 4,600 lines, were devoted to cataloging the various floats and masks of the parade. The book was published at the author’s expense, and unsurprisingly because of its difficulty and obscurity, the literary public responded with almost complete indifference. One reviewer called it “more or less unintelligible,” and another “very boring.” Roussel then experienced something like a plane-crash or a very bad comedown. A period of depression followed, which was recorded by his doctor, the famous psychologist Pierre Janet: “When the volume appeared and the young man, with great emotion, went out into the street and realized that no one was turning to stare at him as he passed, the sensations of glory and luminosity were suddenly extinguished.”

After La Doublure, Roussel wrote three long poems in verse, collected under the title La Vue (1904). The same painstaking attention to detail was given to these poems, and each describes three miniature landscapes, in a sort of Divine Comedy of postage stamps. ‘La Source’ catalogs the image of a spa printed on a bottle of mineral water; ‘La Vue’ zooms into a beach scene on a souvenir pen-holder; and ‘Le Concert’ examines the heading of hotel stationary. Needless to say, sales of the book were very discouraging. The original 550 copies had not been exhausted from the publisher’s warehouse until 1953. Two years later, Alain Robbe-Grillet published his novel Le Voyeur, a text originally titled La Vue in an homage to this miniaturist’s masterpiece.

During the next decade, Roussel switched to prose, in the hopes of becoming accessible to a wider audience. In 1910, he published his first prose novel, Impressions of Africa, which has recently been retranslated by Mark Polizzotti and published by Dalkey Archive Press. The inclusion of Impressions of Africa in their catalog (it situates well in their wonderful collection of experimental world titles) will hopefully enlist a few more Rousselians. The first 130 pages, roughly half, of Impressions of Africa opens with a description of some sort of talent-contest, where a large ensemble of characters called “The Incomparables Club” perform a dreamy sideshow. Narrated with clear and unadorned prose, Roussel describes: Balbet the marksman shooting the white off a soft-boiled egg; trained cats performing a game of capture-the-flag; a giant earthworm that plays Hungarian waltzes on the zither by slashing droplets of a heavy mercurial liquid onto the instrument. Roussel details Fuxier the scientist’s rapid cultivation of grapes with miniature scenes imprisoned inside:

Under the action of the chemical flow, the fruit buds developed rapidly, and soon a cluster of green grapes, heavy and ripe, hung alone on one side of the vine-stock. Fuxier set the jar back down on the ground, having sealed the tube with another twist of the key. Then, drawing our attention to the cluster, he showed us miniscule human figures imprisoned at the center of the diaphanous globes

“A glimpse of ancient Gaul,” says Fuxier, his finger touching a first grape in which we saw several Celtic warriors readying for battle. A few of the other grape encased minatures include Napoleon’s victory in Spain, and a “passage from Emile, in which Jean-Jacques Rousseau lengthily describes the first stirrings of desire felt by his hero upon seeing a young stranger in a poppy-colored dress seated in her doorway.”

The descriptions of the performance have a two-dimensional quality — reportage of supernatural spectacle — with few discernible narrative developments and even fewer subjective characterizations, inspiring a sort of confusion and distance. Like a magician’s act, the reader is more astonished than enlightened.

When the talent show ends, the second half of the book unfolds as an explanation and back-story for the previous events. Here, the reader learns: The Incomparables Club was composed of the passengers on a ship headed toward Buenos Aires. The ship was blown off course to the equatorial African coast, and captured by King Talou VII. The passengers became hostages awaiting ransom from Europe, and while waiting, to avoid restlessness and boredom, they founded “a kind of elite association or unusual club, in which each member would have to distinguish himself through either an original work or a fabulous demonstration.” The club’s performance would coincide with King Talou VII’s decisive military victory over Yaour XI.

The stories and backgrounds of the performance proliferate endlessly, or rather, with a structure that imitates endlessness. Much like in The Arabian Nights, stories contain stories, and narrative seems to expand vertically. The performance itself has a reproductive quality: a machine that paints landscapes, tableaux-vivants, impersonations, echoes, a type of seaweed that records and plays visual loops. The second half is yet another mirror. Everything in Roussel’s universe becomes reproducible, digressive, and vertiginously complicated. These repetitions and images seem to have a lineage through Robbe-Grillet, to Bioy Casares’s Invention of Morel, all the way to Tom McCarthy’s Remainder.

But then, there is yet another layer. Beneath the story is Roussel’s complex network of linguistic tricks: puns, rhymes, and associations. This isn’t readily apparent to the reader — especially one reading the English translation — and could pass by completely unnoticed.

Some years before writing Impressions of Africa, Roussel discovered a poetic technique he called prospecting, which became his trademark compositional method, as well as the foundation for Impressions of Africa. As he explained in his posthumously published How I Wrote Certain of My Books (1935), he would find two almost identical words with separate meanings, and put them inside two almost identical phrases. Then he would establish a connection between the two different phrases, however disparate and roundabout they might be, and write the narrative that linked them together as realistically as possible. For example, the marksman Balbet is a synthesis of two phrases: “1ST Mollet (calf) à gras (fat); 2ND. mollet (soft-boiled egg) à gras (Gras rifle); hence Balbet’s shooting exercise.” And the zither playing worm: “1ST Guitare (title of a Victor Hugo poem) à vers (verse); 2ND. guitare (guitar, which I replaced with zither) à ver (worm).” Foucault described Roussel’s procedure as “a certain way of making language go through the most complicated course and simultaneously take the most direct path in such a way that the following paradox leaps out as evident: the most direct line is also the most perfect circle, which, in coming to a close, suddenly becomes straight, linear, and economical as light.”

Roussel’s prospecting forms images, plots, and characters with a numerologist’s calculated serendipity. At once demystifying and absurdly complicated, his methods inspired Foucault to question the nature and limitations of language and the Oulipians to create their own complicated linguistic procedures.

Like his works before, Impressions of Africa didn’t attract much public attention. But stubborn as he was wealthy, he decided to have the novel rewritten as a play, and staged, all at his own expense. The adaptation, performed in 1911 and 1912, was a public disaster too. But from the play, he seems to have gathered a number of followers, especially those amongst the Surrealists. The performances of Impressions of Africa (described by Mark Ford in his wonderful, comprehensive critical biography, Raymond Roussel and the Republic of Dreams, which most of the biographical information here is reduced from) sound like bawdy, burlesque events that often escalated into shouting matches and physical violence. Duchamp attended one of the performances with Apollinaire and was enthralled by the spectacle. He would later say in an interview, “Roussel showed me the way.”

Between Impressions of Africa and his death in 1933 (a weirdly complicated suicide — even in death Roussel was an enigma — in his hotel room in Palermo), he published one more novel, Locus Solus (a fantastic tour of a mad-scientist’s inventions composed again with his method of prospecting), staged a few more plays, and wrote his last major poem, New Impressions of Africa (completed less than a year before his death). Though it misleadingly suggests an immediate relationship with Impressions of Africa, as far as I can tell, they have little in common, the former being more of a retreat back to his earlier work in La Vue.

The recent translation of New Impressions of Africa by Mark Ford (poet and Rousselian) uses clear English (as opposed to Kenneth Koch’s translation which adheres to the rhyming of the original), is copiously footnoted and contextualized, but is still one of the most complicated poems you’ll ever come across. The long poem is divided into four cantos, each canto divided by multiple parentheses — like concentric circles, sometimes five layers deep — to give each canto a symmetrical structure. On top of that there’s Roussel’s footnotes, Ford’s footnotes, and captioned images (Roussel commissioned an artist through a detective agency and provided concise details for each image, like: “A waterskin in the desert, with water gushing from a hole seemingly deliberately made by a traitor’s sword. No people” or “A woman lowering the sun-blind of a window. The sun-blind is already half-shut, the slats almost horizontal”). The poem is like a crossword puzzle transposed onto a Rubik’s Cube and with each canto, a Whitmanian catalog jammed through a paper shredder. At one point, Roussel toyed with the idea of printing the poem in four separate colors to distinguish between the various levels of the poem but the project was eventually abandoned because of logistical and financial constraints.

The cantos themselves, once reshuffled and absorbed to the best of the reader’s ability, are digressive lists, for example, in the first canto, there are 23 examples of giving unwanted or unnecessary things (“When a lecturer begins, to whoever’s listening,/ A narcotic” or “bellows/ To someone struggling with a fire that is out of control/ In the hearth”) and in the second canto, 207 examples of certain things and their smaller counterparts (“in a boat,/ For two spatulas being used by a chemist,/ A pair of oars” or “for a peach which a prudish/ Person does not look at, the red backside/ Of a naughty child who’s been whipped”).

In 1951, after studying in France on a Fulbright, Kenneth Koch shared his copy of New Impressions of Africa with John Ashbery, who was immediately hooked and wrote, “It seemed impossible that I would ever be able to read it with any understanding, but for a long time it was the thing I most wanted to do. So I learned French with the primary aim of reading Roussel.”

Like all great literature, Roussel should be read with discipline and possession. Roussel will never obtain the popularity he desired, but his work deserves to be more than a secret handshake between fastidious grad-students. His unique style and compositional methods are the footnotes to the canon of avant-garde literature, but his work is also a validation of difficult reading. The recent publication of Impressions of Africa and New Impressions of Africa will hopefully inspire another generation of experimental writers, offering an alternate route to the predictability of well-crafted realism.