-

Becoming Comrades

by Laila Pedro July 8, 2011

Migration, currently at Freight + Volume, is an intimate show with a broad title. The gallery defines the rapport between four artists as a nomadic quality that brings them to the “support and camaraderie of…large urban areas” like “New York (or London or Berlin).” And if this feels a bit too vague and general, the exhibition is minutely scaled and benefits from the attendant specificity; it doesn’t miss the mark, but it could go further.

The work is interesting less for its nomadic creators or themes – whose divergences often make cohesion difficult – than for its focus on the perceptual refractions of the physical, often-feminine and unstable body. This is especially true for the most compelling pieces on display, by Min Hyung and Eunah Kim.

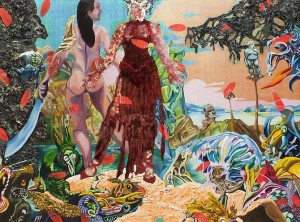

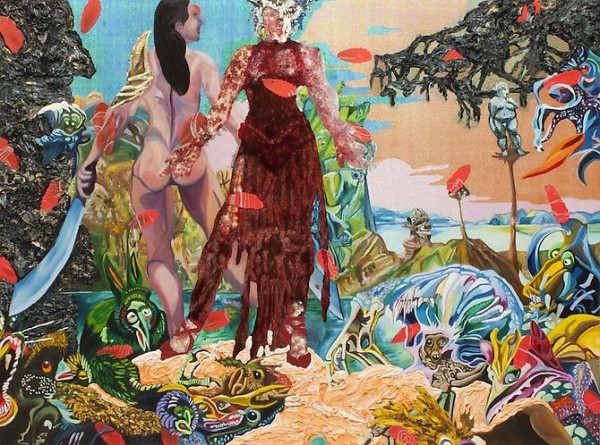

Min Hyung’s big canvases feature an exhilarating diversity of texture and depth, so thick and swirly that they sometimes look edible, like saltwater taffy. Working in a mode we might call ‘epic whimsy’ she flings, swirls, dots, daubs and carefully etches varieties of paint ranging from sheer, gold-flecked Mattel pinks to dense, fat edges whose viscous darkness sucks light from the central figures. These, nevertheless, remain central. Ms. Hyung says she is inspired by Savage Beauty, the McQueen show currently drawing crowds at the Met, and in particular by McQueen’s assertion that “I want to empower women. I want people to be afraid of the women I dress.” Even if this idea of empowering “women” doesn’t quite scan – either in Hyung’s paintings or McQueen’s creations – a kind of archetypal warrior woman is certainly in evidence. A blue-white feminine figure, her back turned to the viewer and holding a sword aloft is a recurring motif in two of the three paintings, in the third she holds a vaguely umbilical thread or rope reminiscent of Frida Kahlo. The influence of fashion, in particular of preparatory sketches for couture collections, is clear in the leggy, statuesque figures, scaled for spectacle, that double down on the McQueen-ish themes of facing/displacing, masking/revealing and directional dislocation. Discerning the fronts and backs of the bodies, despite their flat, declarative lines, is a challenge. The heraldic quality and mutable nature of these bodies adds medieval iconographies to an epic list of references that includes Bosch, Botticelli, Max Ernst, and Delacroix. Each of these operates on and around the body “real” and the body represented. Theorist Jeffrey Jerome Cohen:

Medieval bodies were caught between gravitational forces that pulled them at once toward a fantasy of impossible completeness….and at the same time confronted them with a daily spectacle of of the flesh dissolving into pieces, of bodies composed of metamorphic humoral fluids, of the corporeal as the scene for the staging of magic, holiness, perversity, wonder. Bodies were, quite simply, caught in a process of erupitve becoming.

Hyung’s work shares with medieval bestiaries this fantasy of impossible completeness, of the volcanically transformative potential of the body, even as the contemporary moment injects a mechanical, quasi-bionic quality. The flat figures at center, gilded and half-armored, work as a visual springboard for an entirely other network of bodies; each style relying on another to highlight its specific impact. At the bases of the canvases the eye endlessly recombines a careful mess of totemic, fragmented people and animals, reminiscent of illustration, to produce a menagerie of fantastic beings.

If Huyng is playing with skin, with the multiple registers in which the body’s outside is perceived, Eunah Kim was obsessed with its interior. Kim, who passed away from lung cancer last year, re-worked the intimate, crushing experience of her own insides. Her Happy Lung Flags are exactly that: a series of three flags “made…as a tribute to her besieged lungs and represent the artist’s aspirations for health and happiness.” ‘Aspiration’ is an excellent word here, because Kim’s work is wonderfully devoid of any overt sentimentality; like aspiration, it is direct, action-driven and self-reliant. Rather than impeding emotion, this spareness sharpens it. Hence, Lucy’s Pelvic Bone, a simple and affecting bronze cast of said bone, mounted at a tiny woman’s eye level and without further adornment on the blank expanse of wall. The pelvis is a touching choice, particularly for its sensual, generative functions, which Kim froze in time even as it is rushed from her. It is extraordinary how directly and delicately Kim’s work captures an unimaginable situation even as it refuses maudlin declaration. As the natural lines of bone softly carve the space, making it resonate with their symmetry, the shine of the bronze calls attention to this same effect and codes it with a one-note mark of value. ‘This shines,’ the glint suggests, ‘it is worth something.’

Presented in a small room towards the back of the gallery, Kim’s work is deprived of some of the frame of scale it deserves. This may be because Meredith Pingree’s “kinetic sculptures” and Genevieve White’s installations require more specific kinds of spaces. Pingree’s Magic Curtain looks, at first, like nothing so much as a room-divider in a 1970′s beach house. Sit with it a moment, though, and it reveals its delicate mechanisms, its sinuous, amphibian movement, as it quietly settles you in time and space. It is an unobtrusive presence, one that provides a lovely corporeal context for Migration’s carnal wanderings.