-

Hide/Seek, Culture Wars and the History of the NEA

by Tom McCormack May 4, 2011

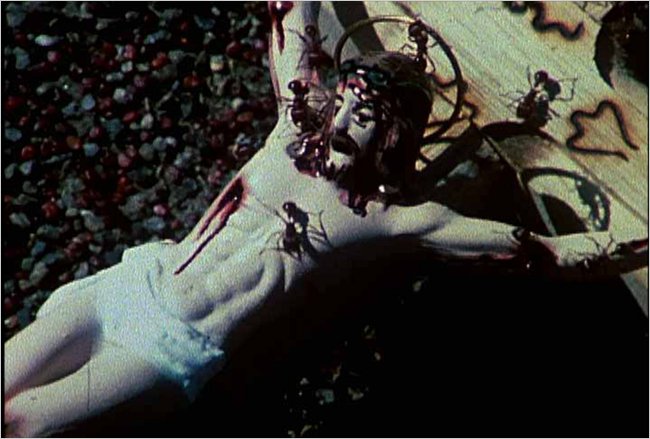

Still from David Wojnarowicz's 'A Fire in My Belly' © Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York (via The New York Times)

1.

It was just a matter of time.

The ball got rolling on November 29th of last year, when Cybercast News Service (formerly Conservative News Service) posted an article to its website titled “Smithsonian Christmas-Season Exhibit Features Ant-Covered Jesus, Naked Brothers Kissing, Genitalia, and Ellen DeGeneres Grabbing Her Breasts.” The article consists mostly of a list of facts regarding The National Portrait Gallery’s exhibit called Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture. These include:

The federally funded National Portrait Gallery, one of the museums of the Smithsonian Institution, is currently showing an exhibition that features … a painting the Smithsonian itself describes in the show’s catalog as “homoerotic.”

The article continues:

A plaque fixed to the wall at the entrance to the exhibit says that the National Portrait Gallery is “committed to showing how a major theme in American history has been the struggle for justice so that people and groups can claim their full inheritance in America’s promise of equality, inclusion, and social dignity.”

And adds, without any real segue:

The Smithsonian Institution has an annual budget of $761 million, 65 percent of which comes from the federal government.

Obviously, something dialectical is going on here, and anyone unfamiliar with CNS’s usual perspective might not get the point until they start quoting economists:

Chris Edwards, director of tax policy studies at the Cato Institute and a former senior economist on the congressional Joint Economic Committee, told CNSNews.com, “If the Smithsonian didn’t have the taxpayer-funded building, they would have no space to present the exhibit, right? In my own view, if someone takes taxpayer money, then I think the taxpayers have every right to question the institutions where the money’s going.”

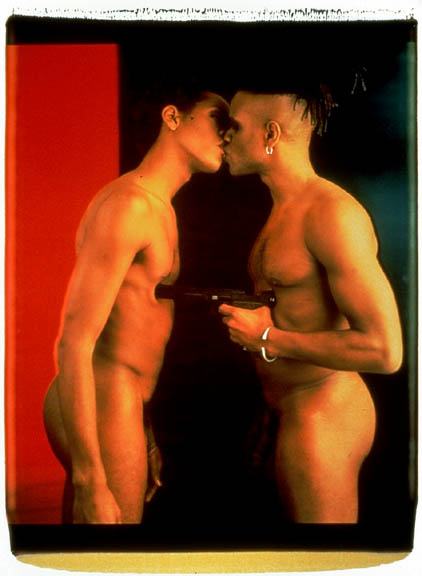

Lyle Ashton Harris, Brotherhood, Crossroads, Etcetera. Via Dawoud Bey.

The article then switches gears again and describes, in deadpan, many of the works featured in Hide/Seek. What isn’t directly quoted from the catalog essay reads like it was. CNS goes into detail describing five different pieces that we can assume they find objectionable, although this is not spelled out. We gather that there are some issues with which they’re specifically concerned: homosexuality and AIDS (the themes of the show itself), nudity, osculatory incest, and the use of Christian imagery, particularly in David Wojnarowicz‘s video A Fire in My Belly.

The story precipitated a national scandal. Congressional representatives John Boehner and Eric Cantor focused on Fire in My Belly, decrying the video’s brief clip of a plastic crucifix covered in fire ants. It’s interesting to consider why they chose this particular work. First, out of all the pieces in Hide/Seek, Belly is the easiest to attack without appearing explicitly homophobic. Second, Boehner and Cantor probably looked for precedent: Belly‘s crucifix bears a striking, though superficial resemblance to Andres Serrano‘s Piss Christ, a photograph of a crucifix submerged in urine that caused a national scandal in 1989. This confusion could help explain the ferocity of some of the rhetoric thrown at Belly. Though Serrano’s piece has been widely misinterpreted, it’s an undeniably incendiary image: Urine is inextricably linked with abjection or degradation (just like the story of Christ, actually). Ants, on the other hand, are, or ought to be, a more ambiguous symbol. Absent some context it’s almost impossible to tell what they mean, but that certainly didn’t stop the taking of some wild guesses.

A spokesperson for Cantor called Belly “an outrageous use of taxpayer money and an obvious attempt to offend Christians during the Christmas season.” The latter accusation is either an obvious act of bad faith or else the kind of wildly transferential thinking that marks romantic relationships (“You were trying to hurt my feelings on purpose!”). It seems improbable that the principals of The National Portrait Gallery, which receives, as was noted, about 72% of its funding from the federal government, had gathered to devise strategies aimed at offending Christians.

Cantor also told the NPG that they “should pull the exhibit and be prepared for serious questions come budget time.” The “and” is significant for not being an “or”. The statement has the ring of an ultimatum, but it isn’t; it’s merely a statement of rage: “Do what we say and, regardless, face our wrath.”

Perhaps the NPG should have taken some time to carefully devise a plan of action. Instead, they immediately removed Belly from the show. The artworld reacted with fury and protest. There were angry letters and activist meetings and Facebook groups; The Museum of Modern Art acquired and immediately displayed Belly; the New Museum showed it; The Andy Warhol Foundation permanently cut all of its future funding to the NPG. In addition, galleries, museums, universities and DIY screening venues all across the country showed Wojnarowicz’s film, while its YouTube popularity skyrocketed. If Cantor et al.’s goal was to limit exposure to Wojnarowicz, it was an epic failure. But in fact this was never the real goal, which was always to cut federal spending on the arts. Throughout the scandal, both Boehner and Cantor stressed that the taxpayers’ money should not be going to the kind of stuff people are calling art these days.

In January, the Republican Study Committee, of which Cantor is a member, released a proposal described as “The Spending Reduction Act of 2011,” a plan to cut federal spending by $2.5 trillion within 10 years. Included in the plan is the total elimination of the National Endowment for the Arts, which at the time received $167.5 million a year. In the recent Congressional budget deal, the National Endowment for the Arts ended up with a 7.5% reduction, yet its battles seem far from over. Cutting arts funding has become a rallying call for fiscal conservatives. In the Congressional deal there are no cuts to the Smithsonian, the parent of the Portrait Gallery, which receives money directly from the federal government and not through the NEA. Fiscally speaking, the NPG might be perceived to have acted wisely.

2.

Hatred of art is nothing new in America.

Cultural critic Lewis Hyde‘s essay, “The Children of John Adams: A Historical View of the Fight Over Arts Funding,” traces the history of US anti-art sentiments back to the nation’s beginnings. The puritans, Hyde argues via Neil Harris‘s The Artist in American Society, “weren’t suspicious of art, they were merely indifferent.” Rather, it was the “‘enlightened rationalism’ of Founding Fathers such as John Adams and James Madison” that “engendered American hostility to the arts.”

Adams, Hyde tells us, “having toured the great English estates and seen the great cathedrals,” thought of art “as signifying the aristocratic and ecclesiastic opulence of Europe.” Adams wrote to Jefferson:

How it is possible [that] Mankind should submit to be governed as they have been is to me an inscrutable Mystery. How they could bear to be taxed to build the Temples of Diana at Ephesus, the Pyramyds of Egypt, Saint Peters in Rome, Notre Dame in Paris, St. Pauls in London, with a million Etceteras…, I know not.

John Trumbull, Declaration of Independence. Via Wikipedia.

And Adams warned the American historical painter John Trumbull:

please remember that the Burin and the Pencil, the Chisel and the Trowell, have in all ages and Countries of which we have any Information, been enlisted on the side of Despotism and Superstition… Architecture, Painting, and Poetry have conspir’d against Right of Mankind.

An irony here is that if you spruce up that last paragraph a bit, it’s the kind of thing that, today, an art historian might devise to impress a tenure review committee. Nowhere will people be more eager to tell you how and why art has, in the words of Adams at another point, “been prostituted to the service of superstition and despotism” than in Art History departments.

The founding father’s skepticism would be elaborated by subsequent generations. Hyde, working off Richard Hofstadter, sees American attitudes about art figured in the presidential races between John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson.

John Quincy Adams did not have the same opinions as his father. According to Hofstadter he was “the last nineteenth-century occupant of the White House … who believed that fostering the arts might properly be a function of the federal government.” Hyde tells us that in the epochal presidential races with Andrew Jackson, “it was exactly on such terms that he was attacked.” The Jackson camp, he writes:

painted [Adams] as an aristocrat able to quote Law but not to make it, able to write but not fight. Jackson, on the other hand, appeared in the popular press as having “escaped the training and dialectics of the schools.” He had “that practical common sense” which is “more valuable than all the acquired learning of a sage.” Such a man could be “raised by the will of the people … to the central post in civilization of republican freedom” precisely because his mind was tarried on “the tardy avenues of syllogism.”

Hyde goes on to note:

The Adams-Jackson campaign may have been the first national event in which “common sense,” that is, a lack of interest in the arts and intellect, was connected to the freedoms of the “common man,” but that correlation has been with us ever since.

The arts and the intellect were associated with education and education with privilege. Valuing intellectual activity was construed as a challenge to egalitarianism because it seemed to render people unequal. Innate qualities had to trump un-innate ones in all respects. Valuing common sense — and only common sense — became a sign that one was in fundamental agreement with the principles of democracy.

In this context, people’s hostility toward contemporary art seems less uniquely contemporary.

But this raises a question. The NEA was started in 1965, and the next 13 years saw the ceaseless expansion of its purview, and near-unilateral support from Congress and the White House. How does this square with America’s uneasy history with the arts?

4.

The groundwork for the NEA was laid during the New Deal, when the Works Progress Administration began employing artists in its Federal Arts Project.1 This was not a move toward patronage; artists were simply considered workers and the WPA was employing them like they would any other worker. It didn’t go off without a hitch. in May of 1938, the House Un-American Activities Committee called in some of the program’s participants for interrogation. When playwright Hallie Flanagan mentioned Christopher Marlowe, Rep. Joseph Starnes interrupted, “Tell us who Marlowe is, so we can get the proper references … is he a communist?” While some red-hunters fretted that the government was subsidizing subversion, the art world, for its part, ended up thinking that, as Joseph Zeigler, a student of federal arts involvement, put it, “they treated artists as propagandists for the New Deal rather than as servants for the nation.”

But the precedent for government support of the arts had been set. Never before had the nation systematically funded art and by the time the WPA shut down in 1943 some saw its arts patronage as precedent for a more comprehensive program. Lacking strong leadership however discussions in Congress stalled.

It was John F. Kennedy who revived the idea. Kennedy was not actually highbrow, but his wife was, and he enjoyed appearing to be as well. Many in the art world were pleased when Kennedy not only invited Robert Frost to read at his inauguration but also made sure the audience was filled with prestigious intellectuals, including Mark Rothko, Franz Kline and Alfred H. Barr. Kennedy induced general euphoria among the thinking classes. In December of 1960, Musical America announced, “We shall have a man in the White House who will feel as responsible for American civilization as he does for American power and prosperity.”

However Kennedy’s major contributions to the arts were more symbolic than substantive. Mostly he and his wife enjoyed hosting parties with people like Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, Andrew Wyeth, Robert Lowell, Arthur Miller, and Tennessee Williams, but the President’s reputation as an art lover was important. Some of the major steps in establishing the NEA were taken in the spirit of memorializing Kennedy. That Jacquelyn Kennedy once said of him, “The only music he likes is ‘Hail to the Chief,'” is an irony that at the time remained private.

The major push for establishing the NEA came from elsewhere, and was born of a culture war not entirely different than the one now threatening the agency with extinction.

5.

Intellectuals made two distinct but interrelated arguments for funding the arts. First, that a newly-minted army of corrupted, mindless drones, spawned by a perverse and triumphant consumer culture would drag the country into the gutter of terrible taste and crass materialism. And, second, that this picture of America was gaining traction in foreign countries, countries that needed to be suitably impressed with the products of freedom lest they be seduced by Soviet-style communism.

Historian Donna Binkiewicz traces the first attitude back to William Whyte’s 1956 The Organization Man and David Riesman’s 1950 The Lonely Crowd. Whyte argued that the modern workplace demanded that men place the needs of companies above their own, therefore encouraging bland conformity. Riesman argued that the American man was changing from being “inner-directed,” driven by his own self, to being “outer-directed,” driven by the desires of the group. Riesman phrased this difference in terms of “softness” and “hardness”: “Today it is the ‘softness’ of men rather than the ‘hardness’ of material that calls on talent and opens new channels of social mobility.”

As Congressional hearings regarding arts legislation got under way during the Kennedy administration, it became clear how married the concerns about popular culture were to concerns about the spread of communism. Senator Jacob Javits said that “the Russians have gotten more benefit from sending Oistrakh, their violinist, the Bolshoi Ballet and the Moiseyev Ballet to the United States than they have from Sputnik.” He argued that America needed “first to assert the efficacy and the virtues of our free institutions, and second, to make human beings throughout the world feel that we are people who deserve to be followed.” Rep. Seymour Halpern added that art could “act as a potent weapon on our struggles against atheistic, materialistic communism, for it would prove that creativity — as well as economic and political-social development — can be encouraged and flourish in a free society.” Rep. Carroll Kearns really brought the issues home, invoking “Ivan,” and “Little Johnny,” to represent the Russian and the American school child respectively:

Ivan and European children are exposed from their earliest days to the finest cultural expressions, to the greatest classics of our Western cultural heritage, to the opera, the theater, and to great art in all fields. Little Johnny, on the other hand, sees the Three Stooges, and all kinds of trash on the TV programs at home, and when he goes to the movies he is not any better off.

But then what to fund? It would have to stress individuality over corporate conformity, be “inner-directed” as opposed to “outer-directed,” hard instead of soft, and it would have to outshine Soviet art in the eyes of Europeans, speaking in a visual language they could understand, but modifying it in a way that was distinctly American. And it would have to clearly say: Freedom.

6.

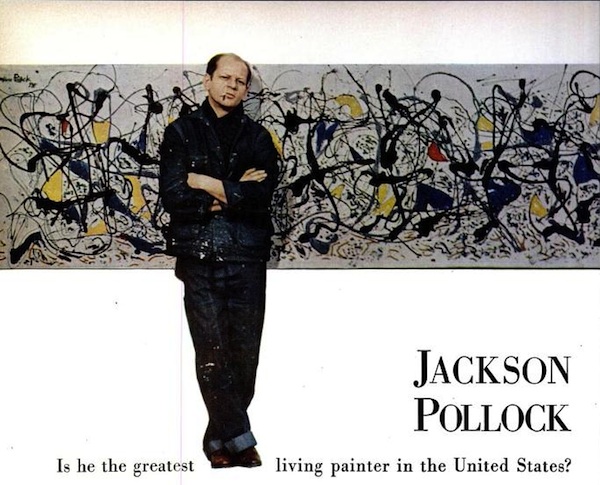

In the late 40s and early 50s, Life magazine trumpeted the work of New York School painters in a series of widely read articles. Historian David Joselit writes:

It was Life magazine with its vast readership and authoritative voice which could confer celebrity on an artist through its coverage, and it was Life which chose Jackson Pollock for such attention in a 1949 feature articled titled “Jackson Pollock: Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” Many have noted that Pollock’s portrait in Life, in which he stands, sullen and defiant, with arms crossed and a cigarette hanging from his lips, virtually eclipsed the painting Summertime which hung behind him in the picture. Pollock’s gruff persona accords perfectly with pre-existing notions of the American hero (or anti-hero) — from cowboy to Hell’s Angel — in qualifying him to occupy the position of artist-as-rebel. Such rugged individualism was exactly what the readers of Life wanted from an artist and this was what the magazine delivered. Despite the often derisive tone of the text with regard to Pollock’s painting, the artist’s portrait truly spoke more eloquently than words — and indeed, in this context, more eloquently than his works as well.

Jackson Pollock in Life, August 8, 1949. Via Google Books.

Abstract Expressionism was presented to the world, in the pages of Life, as individualist, “inner-directed,” and “hard.” Life used radically-simplified means to convey this, but the message was not entirely inaccurate.

In more high-minded intellectual circles, Abstract Expressionism was presented by critics like Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg as America’s triumph over European art through an improvement on European avant-garde styles. For Greenberg, is was the most recent stage in a development that started around Cézanne and had previously peaked with Cubism. As the art historian Serge Guilbaut has written:

Greenberg emphasized the greater vitality, virility and brutality of the American artist. He was developing an ideology that would transform the provincialism of American art into internationalism by replacing the Parisian standards … (grace, craft, finish) with American ones (violence, spontaneity, incompleteness.) Brutality and vulgarity were signs of the direct, uncorrupted communication that contemporary life demanded. American art became the trustee of this new age.

It would only be a slight exaggeration to say that the NEA was founded in order to fund Abstract Expressionist work. That was, for its first few years, mostly what it did. Abstract Expressionism fit the bill for what America wanted to fund having proved itself a useful weapon in the Cold War. In fact, where Abstract Expressionism is concerned, there had already been a national endowment for the arts for almost two decades it was called the Central Intelligence Agency.

Throughout the 50s and 60s, the CIA had worked in secret parallel to the US Information Agency in funding American art, often funding the Museum of Modern Art via the charity trust of John Hay Whitney, chairman of MoMA’s board. Whitney had spent the war in the employ of the OSS, precursor to the CIA.

In an October 1995 article published by The Independent, Frances Stonor Saunders detailed the AbEx ops, getting ex-CIA officer Donald Jameson to tell how it happened. “The new American art,” wrote, Suanders, “was secretly promoted under a policy known as the ‘long leash’ — arrangements similar in some ways to the indirect CIA backing of the journal Encounter, edited by Stephen Spender.” Starting in 1947, “the new agency set up a division, the Propaganda Assets Inventory, which at its peak could influence more than 800 newspapers, magazines and public information organisations.”

Jameson told Saunders:

It was recognised that Abstract Expression-ism was the kind of art that made Socialist Realism look even more stylised and more rigid and confined than it was. And that relationship was exploited in some of the exhibitions.

In a way our understanding was helped because Moscow in those days was very vicious in its denunciation of any kind of non-conformity to its own very rigid patterns. And so one could quite adequately and accurately reason that anything they criticised that much and that heavy-handedly was worth support one way or another.

The agency made its support a secret, from both the public and from the artists it was subsidizing through funding foreign exhibitions, supporting and convincing museums to show the work, and, perhaps most significantly, encouraging wealthy art collectors to become regular patrons.

The NEA, the original ranks of which consisted of many curators, critics and artists involved in Abstract Expressionism, was in some ways just the making public of this secret program.

7.

It was LBJ who, after Kennedy’s death, pushed the legislation that established the NEA through Congress. Aside from the Cold War, Johnson had other political and perhaps personal reasons for supporting the endowment. It would be part of his Great Society, which was “engaged not only in a war against the poverty of man’s necessities, but in a war against the poverty of man’s spirit.” Also, like Kennedy, Johnson was influenced by his wife, Lady Bird, who loved art and moved within its world, even speaking at MoMA in 1964. Johnson said his wife’s passion “stirred a very considerable interest in [him].”

Johnson lobbied for an arts endowment and, in a smart move, married it with the establishment of an endowment for the humanities, which helped garner more support by linking the arts to broader goals in education. In 1965, the agency was established.

A major Democratic fundraiser and head of the Kennedy Center, Roger Stevens was named first head of the NEA. Susan Sontag, somehow, had been seriously considered, but that idea was put aside after an FBI background check revealed her strong opposition to the Vietnam War.

The project started out modestly, with $2.5 million, and under Stevens it grew modestly, rising only to $3.7 million by the time he left. Without much money, nothing too ambitious could be done. A lot of money was put toward work that could either be called Abstract Expressionist or could be said to be inheriting similar concerns. According to Binkiewicz, in 1967, 68% of funds allocated for individual painters or sculptors went to artists with “abstract expressionist, color-field, and geometric abstractionist aesthetics”; 75% in 1968; 85% in 1969. At a time when the modernist vision of art was being destabilized by movements like Pop Art, the NEA, as Binkiewicz put it, “defined artistic excellence as modernist abstraction.” By no means did all the money go in that direction, but it was a noticeable bias.

LBJ was proud of the NEA. Early on, he and actor Gregory Peck visited rural theater companies enjoying NEA support; Peck remarked to Johnson, “Wouldn’t it be great if the American Shakespeare were to emerge from one of the new federally backed theaters?” “Do you know what would be even greater?” said Johnson, “If the American Shakespeare turns out to be a black man.” Johnson was expressing a genuine urge for the Endowment to promote diversity. That this is precisely what happened, didn’t prevent a lot of people from getting very upset.

When Nixon took office in 1969, the art world was worried. At first, he did nothing to assuage their fears, letting Roger Stevens’ term of appointment expire despite his widespread support in the cultural community. But Nixon’s appointment of Nancy Hanks as his replacement would prove to be perhaps the most important event in the history of the NEA. Not directly involved in the art world, Hanks was an art admirer who had worked for Nelson Rockefeller. She was, perhaps above all, a brilliant politician at a time when women had few options in politics; had she been born at a later date it is likely she would have been the one doing the appointing. After letting it be known that she would be called Chairman and not Chairperson or Chairwoman, she charmed Nixon, made friends with Congress, and oversaw the growth of the Endowment’s yearly budget from $8 to $161 million, averaging a 161% increase over the eight years of her tenure. Liked by most everyone, she was dubbed the “mother of a million artists.”

For all her talents, Hanks couldn’t have succeeded without Nixon’s support. Why did the resentful, anti-elitist Nixon become the NEA’s greatest presidential benefactor? There are three probable reasons. The first is that Nixon was an avid cold warrior and he continued to see the NEA as useful in the worldwide struggle for hearts and minds. Second, Nixon increasingly saw the arts as a way to reach out to the people he felt alienated from, particularly youth. The arts, he thought, were good PR. The third reason is that Nixon and Hanks were equally invested in a shared vision for the NEA. Their Endowment would decentralize American art, moving production away from the coastal elites and out to the people. This required big money. With a small budget, egalitarianism was hard. Hanks explained to Nixon that smaller grants couldn’t do things like bring symphony orchestras to the Midwest. As more money started coming in, more of it went to things like realist painting, traditional crafts, folk and community art centers and youth programs. The trend would continue beyond Nixon and into the late 70s.

Nixon and Hanks’s wish for a decentralized artworld should be considered alongside the spirit of the 1970s avant-garde. Conceptual art was challenging the commodity status of the art object, among other things. Artists engaged in institutional critique were trying to unearth the role institutions and ideologies played in shaping social space and cultural production. With the arrival of land art, fine art was no longer confined to the gallery. There was an expanding of frames and a dissolving of boundaries as artists forsook the legacies of a certain modernism. There was a general embrace of pluralism; and the pluralism of forms found itself at home with the kind of pluralism the NEA was pushing for. The New York art world that Nixon and Hanks were trying to move beyond was trying to move beyond itself. The NEA and the avant-garde were, in a sense and for a moment, complementary projects.

Historian David Smith offers a look at just how much the NEA’s priorities had changed by 1980, after Hanks had been replaced by Livingston Biddle,:

The Endowment began a “National Crafts Planning Project” to measure the needs of potters, metalsmiths, and weavers; gave $60,000 to establish a textile museum in Washington, DC: gave $40,000 to stage an “International Festival of Mime”; designed and pledged more support for jazz artists; and organized an exhibit of Hispanic art “to promote the NEA within the Hispanic community.”

This was how the NEA was running when, in 1981, the Reagan administration began pushing for serious cuts. Chairman Livingston Biddle didn’t believe it was purely about fiscal conservatism and sought out an explanation from a Reagan aide. As Biddle recounts in his autobiography:

Why cut the arts so deeply? I asked. What was the real rationale?

It was simple, I was told. The endowment was supporting art that the people did not want or understand, art of no real value.

Now there’s a question worth asking: If the story of the Endowment in the 70s is a story of decentralization and pluralism, if the Endowment was funding community arts centers and youth programs and potters and metalsmiths and weavers and textile museums and mimes and jazz musicians and Hispanic art, to whom, exactly, did the NEA have “no real value”?

Revolutionaries like to point to the haves and the have-nots, often indicating material differences between classes. The Reagan revolutionaries — a group in that includes the Christian Right and the Moral Majority — preferred mobilizing people over symbolic differences. America offered plenty of ready-made symbols. The arts themselves have been symbols of difference, and the NEA, with its pluralistic reach, had absorbed a number of them.

9.

The NEA crisis that started in 1989 was by no means the first time that people in Congress had raised objections to the institution. As a matter of fact, the history of the NEA is filled with such disagreements.

The first to raise a fuss, unsurprisingly, were representational artists who felt grossly under-served during the first years of the NEA. Notes from a Congressional hearing in 1967 read:

Frank Wright, president of the Council of American Artists Societies, stated: “Works of artists already awarded grants include some appalling selections, and only eight out of 60 can be called representational … No one can complain if a painter wants to have a tantrum on canvas … But to call the results art is something else.” … As Senator Pell concluded the hearings he … said he hoped that the exchange of opinions had cleared the air, and that … “encouragement should be given to forms of art that have a message or at least we can comprehend.”

Promoters of representational art were particularly distressed by the fact that the names of NEA panelists were not released to the public, so it was impossible to tell who was initiating these biases; so, in order to promote transparency, Congress moved to release panelists’ names after the panelists had made their decisions.

The first work of art to anger actual members of Congress was Aram Saroyan‘s poem “lighght,” published in the second edition of the American Literary Anthology, a book edited by George Plimpton and underwritten in part by the NEA. Saroyan’s poem consisted only of the neologism “lighght,” which appeared in the middle of a blank page. Rep. William J. Scherle got up in Congress to announce, “If my kid came home from school spelling like that, I would have stood him in the corner with a dunce cap.”

When Scherle had an aide call Plimpton for comment, Plimpton, ever the politician, told the aide, “You are from the Midwest. You are culturally deprived, so you would not understand it anyway.” Nonetheless, Hanks managed to defuse the situation and the whole thing fizzled out. Then in 1970 Plimpton almost caused another scandal. It reached Hanks that Plimpton was going to publish, partly with money from an NEA grant, a third volume of the Anthology that included a short story called “The Hairy Table” by Ed Sanders. “The Hairy Table” opens thusly:

Her delicate tongue of flame slid into the crinkles of my ass, jabbing here like a sparrer, sucking there like a cuttlefish dragged from its hole. I filled her snatch full of air and gently drew it out in cunt-spurts, tasting the salmon moisture of the wheezes.

Hanks was alarmed. She asked Plimpton to remove the story. He refused. Joseph Zeigler:

Hanks … went straight to New York to negotiate with Plimpton. Hanks announced that she was canceling the anthology after the third volume appeared, which meant that Plimpton would have to find other funding for the fourth edition already being planned. He decided to excise The Hairy Table from the anthology supported with NEA money, and include it in another edition that was printed with private sector money.

Through continued support, Hanks effectively had Plimpton on payroll, and she could, and did threaten to fire him, effectively.

In 1974, NEA grantee Erica Jong published Fear of Flying. The book was a succès de scandale, and many people wrote their Congressman to complain. Jesse Helms, who by his own admission had not read a word of Fear of Flying, was outraged. Helms sent Nancy Hanks an angry letter, insisting that she A) must think it was not obscene, B) must think its artistic merit outweighed its obscenity, or C) must be in the process of demanding that Jong return the money. Hanks replied, trying to explain that the NEA gave money to artists to do whatever they wanted, that the NEA couldn’t exercise oversight on the work produced, that it could only judge merit based on past work. Helms wrote back that A, B, and C were the only logical options in this situation. However, although the NEA was facing re-authorization hearings, Helms failed to marshal enough support to damage the endowment.

Both Scherle and Helms had been outraged, but they had failed to find traction in the halls of Congress. In June of 1987, President Reagan traveled to the Berlin Wall to give a speech. Today, the speech seems less notable for its influence than for its tone of inevitability: “Yes, across Europe, this wall will fall. For it cannot withstand faith; it cannot withstand truth. The wall cannot withstand freedom.” Whatever the agency of its demise, two years later the Wall was gone, and the Cold War had ended. In the summer of 1989 Congress furiously debated the status of the NEA and, with the threat of international communism on the wane, if not dispelled, opponents of the endowment found they had traction for the first time. A lot, actually.

10.

1989 began a period of crisis for the NEA that would stretch well into the 90s. Controversy over work by Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe set things in motion. Other artists to get swept up in controversy include Karen Finley, Tim Miller, John Fleck, and Holly Hughes, “The NEA Four” (1990). But the first group exhibition to find its funding challenged as a result of the NEA battles was Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, a late 1989 show which dealt with homosexual culture and AIDS.

Karen Finley in Shut Up & Love Me. Via TMA Review Archive

In 1995, Newt Gingrich asked in Time, “Why is it in the best interest of a country to continue funding that which contributes to its cultural fraying?” There could be little doubt on either side of the debate just what “fraying” Gingrich was referring to.

But it’s a mistake to think that hostility toward the NEA is merely a symptom of widespread skepticism regarding contemporary art as such. Since the 90s, the NEA’s most voluble critics have not been those who think that conceptualism, video art, performance art, inter-media, experimental film, minimalism, post-minimalism and relational art combined have nothing on Quattrocento painting, Gothic architecture or Attic tragedy. These critics, in fact, are the people who have been running the NEA recently. In 2002, George W. Bush tapped Dana Gioia as head of the agency. Gioia gained prominence when, in 1991, he wrote an article for the Atlantic called “Can Poetry Matter?” wherein he excoriated contemporary poetry for becoming indrawn and alienating its audience. “Like subsidized farming,” he said, “that grows food no one wants, a poetry industry has been created to serve the interests of the producers and not the consumers. And in the process the integrity of the art has been betrayed.” This is the standard language of reactionary aesthetic conservatism. But Gioia was not a man who believed in shutting down the NEA; he fought very well to expand it.

Even if we were to imagine that the anti-NEA lobby was motivated by simple fiscal conservatism, the tools they use to marshal support move beyond the numbers. In this respect, fights over the NEA are exemplary of interest-group politics. The destruction of social programs often require provincializing the body politic to the point where a common interest appears particular. Artists already stand apart in the minds of many, but NEA outrages have focused specifically on homosexuals, women, and people of color.

It was no accident that arts funding was once again brought to national attention with the exhibit Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture. Since the 80s, the enemies of the NEA have not been those with differences of opinion about what art should be supported or how. Instead they oppose any support at all for art of any kind. For them, destroying the NEA would be just one step in the right direction.

- I construct my history on three books: Arts in Crisis: The National Endowment for the Arts Versus America by Joseph Wesley Zeigler, Federalizing the Muse: United States Arts Policy and the National Endowment for the Arts 1965-1980 by Donna Binkiewicz, and Money for Art: The Tangled Web of Art and Politics by David A. Smith. And what follows has been undoubtedly shaded by the various programs of Smith, a cultural conservative; Zeigler, a moderate; and Binkiewicz, a liberal. [↩]