-

Aggressive Nostalgia: On Chaos and Classicism

by Stephen Squibb January 7, 2011

Kenneth E. Silver’s Chaos and Classicism: Art in France, Italy, and Germany 1918–1936, closing presently at the Guggenheim, has been justly celebrated as a timely, fascinating and refreshingly serious exhibition. An audacious presentation of largely marginal works, the show banks instead on the historical and intellectual appeal of its theme: the return of classicism in the interwar art of Italy, France and Germany. The show’s immediate success, palpable almost upon arrival, speaks not only to the diligence and command of its curators, but to a deeply felt resonance between its moment and our own. What makes Chaos of lasting interest, however, is precisely the extent to which it disrupts this easy parallel: it is difficult to walk away from this exhibition with one’s ‘we are Weimar’ fatalism fully intact. Illuminated instead are the differences between our homegrown forms of Rightist reaction – at least at the level of art and culture – and those of Italian and German fascism. Put simply, it is hard to imagine any of our contemporary demagogues having any paintings at all above their mantle, even ones as kitschy and ridiculous as Adolf Ziegler’s Four Elements: Fire, Water and Earth, Air, which enjoyed pride of place in Hitler’s Munich apartment and performs as the tawdry climax of Chaos. Perhaps Sean Hannity just loves Thomas Kinkade, but I doubt it.

The story being told is familiar at the level of sociology but is often eclipsed art-historically by our fascination with the avant-gardes, whose provocations never penetrated the popular imagination to the extent of the work shown here. Europe, deeply disturbed by the savagery of the First World War, sought refuge in classical forms whose very appeal belied their distance from industrial civilization. The lingering trauma of The Great War was sublimated into a desire for the purity, order and clean lines of antiquity. That these forms were always ideological – there was nothing particularly pure, clean or orderly about Rome or Athens at the level of lived experience – accounts, bizarrely, for their allure. Indeed, what is so striking about the interwar classicist revival is just how consciously it was pursued – a fact elegantly detailed in Silver’s catalog essay, “A More Durable Self.” It was precisely the anti-realism of classicism, when realism would have meant a lifetime of images like those of Otto Dix, which made it so broadly seductive. And here the architecture of the Guggenheim really is put to spectacular use. We are literally lifted us away from Dix’s etchings, here located on the ground floor, and into the airy realm of ideal types, rehearsing the flight of the history on display.

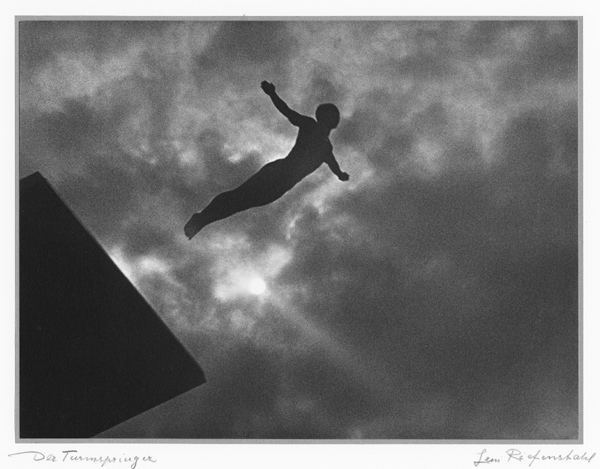

As we progress up the spiral towards the inevitable, symbolized not only by the aforementioned Ziegler but also by Leni Riefenstahl’s show-stopping Olympia, what stands out is the clarity of the opposition between Right and Left cultural positioning. Unlike today, that is, where sexism, racism and homophobia are re-branded as one side in a ‘culture war’ for which they have neglected to show up as art, in interwar Europe there actually was a contest between two competing accounts of what painting and sculpture can and should be. Fascists, whose terrible taste is on such ample display as to achieve a kind of grim hilarity, still felt that art was worth fighting for. Today’s Right just wants it to go away.

It will perhaps be objected that the Tea Party’s open pining for the days of lynching, indentured sexual servitude and the twelve hour work-day amounts to a kind of crypto-classicism, because nostalgic, aggressive and unmoored. But this is to miss the central, negative insight made available by Silver’s work, which was touched on in an online forum. Here Julian Stallabrass made reference to Perry Anderson’s linking of classicism to an aristocratic legacy, which Martha Rosler then furthered by citing the criminally under-appreciated Andreas Huyssen. Huyssen makes clear that neither modernism, American or European, can be properly understood without reference to the distinctions between those continents’ respective social histories. Without the canonization of Euro-modernism, the American modernist moment would never have been ‘post-’ in any meaningful sense. Similarly, without an aristocratic heritage of our own, the categories of European political history – and the contours of their aesthetic ideologies – cannot be imported wholesale. And this, finally, is what makes Chaos and Classicism so valuable: by presenting the reality of the fascist shift in European art, the Guggenheim stymies the central positioning of that moment within the American political imaginary. We may be headed towards disaster, if we are not there already, but this tragedy, when it arrives, will be a farce of a different color.